Finding the entry points in Chicago’s poetry community

Hearkening back to the days of Gwendolyn Brooks, Chicago has a history of making sure poetry is for everyone — despite ability or academic experience. Brooks’s first anthology “A Street in Bronzeville” seemed to cement this idea in 1945 Chicago.

“I wrote about what I saw and heard in the street,” The New York Times quoted Brooks in her obituary. “I lived in a small second-floor apartment at the corner, and I could look first on one side and then the other. There was my material.”

It’s exactly this street poetry that draws emerging writers to Chicago today. The challenge has now become ensuring poetry is still for the everyday person, still thriving safe outside the walls of academia and bursting out onto Chicago’s streets.

This Tuesday evening, for instance, the Poetry Foundation hosted their monthly Open Door Reading series. While the door is open literally (free, open to the public), this reading series also hopes to open a more figurative door into the literary community.

The Open Door Reading series features readers in pairs — two Chicagoland writing program instructors and two of their current or recent students, according to the Poetry Foundation website. This week’s reading featured Marty McConnell and her student Ola Faleti, as well as Columbia College Chicago’s T. Clutch Fleischmann and their student Sung Yim. By pairing more established teachers of poetry with their emerging students, the reading series not only brings exposure at a traditional institution for those hoping to break into Chicago’s poetry scene, but also creates a space in which young poets can access the craft.

Faleti and McConnell first met in McConnell’s Logan Square living room for an informal poetry workshop about two years ago. These workshops, called Vox Ferus (Latin for “fierce voice”), aim to bring together a community of writers passionate about writing and revising their poetry. After receiving her MFA in creative writing/poetry from Sarah Lawrence College in New York and moving back to Chicago, McConnell wanted to contribute to the Chicago poetry community in a productive way. She saw a gap that she was able to fill — the need for a nurturing and educational poetic space that didn’t lean on academic experience.

“That’s what I was really most interested in — that we can build spaces where people might have advanced degrees in this [or] might not know anything about it, but can really come together and just talk about poems,” McConnell said.

Faleti, who grew up in Uptown and started coming to the workshops in McConnell’s home just over two years ago, has found that to be the case. Even if she’s not having a poem workshopped that month, she finds the community environment valuable to learning.

Faleti and McConnell both find it important to reflect on how poetry has traditionally been taught in schools, from the first grade onward through high school. Young people are often taught to see poetry as something academic and rigid, they said, with line breaks and forms to follow. While this is and certainly can be true, it’s not the only way to read or write a poem.

“What I don’t want is for the language of poetry to be a barrier for people analyzing it,” McConnell said. “My basic theory is that if you can read, you can read poetry. It’s just words on a page.”

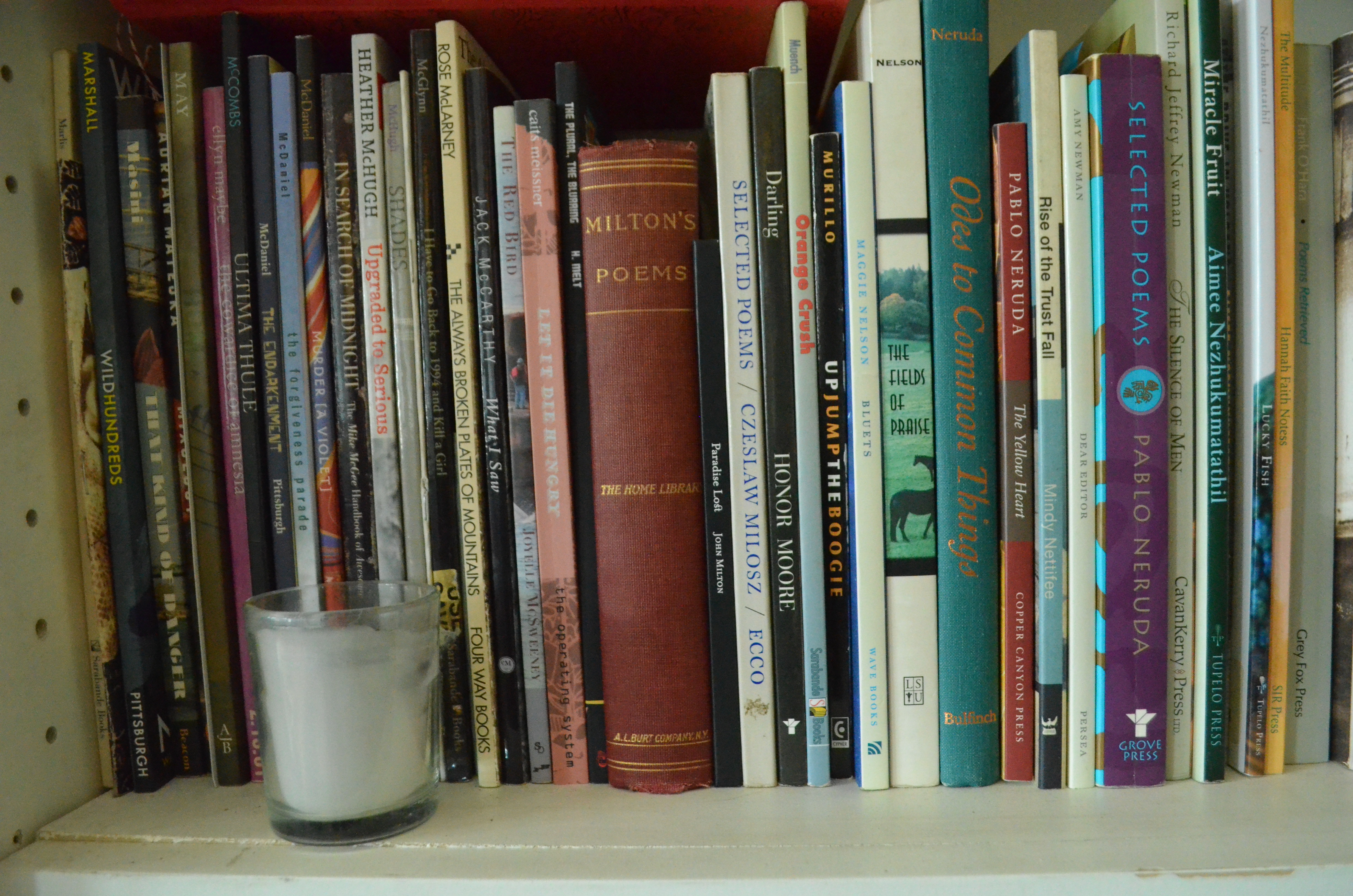

Photos of McConnell and her workspace. (Megan Stringer, 14 East)

Some groups in Chicago have been revolutionizing ways to teach poetry to youth. Young Chicago Authors, whose organizers and teachers include renowned local poets like Jamila Woods and Nate Marshall, aim to expose young people to hip-hop and poetry, teaching them to “create their own authentic narratives…both in and out of the classroom.”

826CHI is another, a Wicker Park-based nonprofit that holds both tutoring and workshops to help encourage young people in their creative writing. Faleti works at 826CHI as a development coordinator writing grants.

Ola Faleti (Megan Stringer, 14 East)

She’s also surrounded by young people working to improve their writing every day after school during tutoring sessions. Faleti finds inspiration in the chapbooks (independently released books with a small circulation) 826CHI’s students put out — particularly last semester’s, which she said was poetry-heavy.

She especially likes seeing this sort of creative writing education as it differs from her own experience learning poetry in primary school. She remembers a lot of kids growing up found the poetry unit boring, reading work from the era of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

“Nothing against them, but it just makes poetry seem like such a stagnant thing, to constantly look at the work of people who wrote like over a century ago,” Faleti said. “Poetry is so relevant and so alive, and it’s literally everywhere. I think that that’s something that should be celebrated more.”

Sung Yim, a Chicago-based writer who also read at the Poetry Foundation’s Open Door Reading series this week, agrees it’s important to create accessible spaces for new writers to learn and grow. Although they don’t consider themselves a poet because of their larger beliefs about genre and form, they believe it’s important to have spaces where “the lay person could just come in and be like, ‘Oh, what’s going on?’ and engage with the work in a way that doesn’t make the writers feel like far away idols.”

“I think there should be less separation between audience and writer,” Yim said. “We’re all just doing the same thing.”

Reaching this realization is what can really bring poetry outside the classroom. “Poetry — even on a street level — it’s everywhere,” Faleti said. “It’s there if you look for it.”

McConnell’s second poetry collection, “when they say you can’t go home again, what they mean is you were never there,” is forthcoming in fall 2018 from Southern Indiana University Press.

NO COMMENT