Construction of identity, sexual gatekeeping and the rise of Masc4Masc in queer digital spaces

In the new millenium and the rise of digital spaces, social networking sites became a way to form specific subcultures on the web. YouTube and Flickr built community around wanting to share digital media, LinkedIn built community around business and professional relationships, BlackPlanet built community around similar ethnic and racial backgrounds, and Match and Chemistry pioneered what would be an ever evolving culture of online dating.

For queer men, social networking sites (SNSs) provided the underground space to find gay friends, sexual partners and experiment with sexuality in ways they could not do publically in the real world. For the queer community, nothing has been more sacred than the underground space. A place that can change with time where one can express themselves authentically without judgement for their sexual or romantic desires or the risk of violence. Before World War II, where anti-gay sentiment was the mainstream ideology, the underground space existed in “subcultural codes,” as defined by George Chauncey in his book “Gay New York.” Queer men would wear colored handkerchiefs in their jean pockets, leather, or acted in an understood code of speech and style to be recognized by fellow gay men and avoid harassment in public spaces.

In the digital era, this underground space exists in the form of social networking sites, or SNSs. On explicitly queer SNSs like Grindr, there is a phenomenon known as “Masc4Masc,” which deems the hypermasculine or straight-passing user the most desirable and often reflects hegemonic and heterosexual ideals of masculinity. Where queer digital spaces were forged for safe expression of identity, more often than not SNSs like Grindr establish a gatekeeping of what is desirable and mimics the toxic spaces and ideologies they were trying to avoid in the first place.

Grindr is the most popular gay mobile SNS on the market. In its first three years, Grindr reached over 4 million users in 192 countries. According to data released in 2016, Grindr serves roughly 5 to 6 million monthly users, 2.4 million daily users and hosts 1 million active users at any given time. Grindr is unique because of its emphasis on geolocation. Unlike SNSs like Facebook or even dating SNSs like Tinder, Grindr uses the phones’ GPS to find the closest available users in the area. Grindr is also explicitly about casual gay sex, whereas other dating SNSs on the market might target both straight and gay users with a focus on romantic or platonic relationships instead of sexual ones.

“For sexual minorities routinely discriminated against in the off-line world, online environments can oftentimes be a safe space to connect with others and explore sexual identities,” said David Gudelunas in There’s an App for that: The Uses and Gratifications of Online Social Networks for Gay Men. In the rise of the internet, queer men have traded colored handkerchiefs for online profiles and have created a similar community in the digital space without having to out themselves before they’re ready.

In many ways, Grindr is “cruising” for the internet. Cruising is defined as looking for casual sex in public places and is considered a queer specific term in the United States. Queer men often cruise in gay bars, public restrooms (either in bathroom stalls or through the use of gloryholes: a hole carved in the wall of a bathroom stall where gay men could anonymously engage in oral sex) or in outdoor public places like parks. Cruising also functioned as a subcultural code, where queer men were in the know and could express their sexual intentions without outing themselves publicly. Grindr mirrors cruising in multiple ways: its emphasis on location and proximity and its explicitness of sex as an end goal — not only from the platform itself, but from the behaviors of the users.

Photo: James Patrick Dawson, XY Magazine.

The Grindr profile is the foundation of the queer male identity in the digital space, and sets the framework for sense of self as well as what is considered sexually desirable in the community. The profile on Grindr is composed of a few basic variables: a photo, demographic information like age, weight and ethnicity, as well as a short caption that describes who the user is and what they’re looking for. In Masc4Masc culture, this caption is often used to praise masculine men and tear down feminine men as shown in the website Douchebags of Grindr, a submission based website that collects screenshots of Grindr profiles based on different levels of “douchebag-ness.” Some of the most popular tags are “racism,” “femmephobia” and “body nazi,” which indicates users who expect physical fitness in their sexual partners. In the “femmephobia” tag, one profile boasts the bio “I’m a gay GUY! If I wanted to date someone feminine I’d be straight and with a girl.”

In framing masculinity and anti-effeminacy in queer dating SNSs, Brandon Miller and Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz claim in “Masculine Guys Only” that “the expression of anti-effeminacy attitudes may be motivated by a need to be accepted by others,” and that “Femmephobia framing demonstrates adherence to a masculine ideal within the gay male culture, an ideal promoted by anti-effeminacy attitudes and the privileging of masculine presentation.” Since masculinity and physical fitness act as the standard of male beauty within heterosexual norms, hyper-masculine body standards in the queer community are a direct reflection. By mimicking these beauty standards, queer men craft what is desirable from the need to feel accepted by their straight counterparts and to gain power in their queer communities.

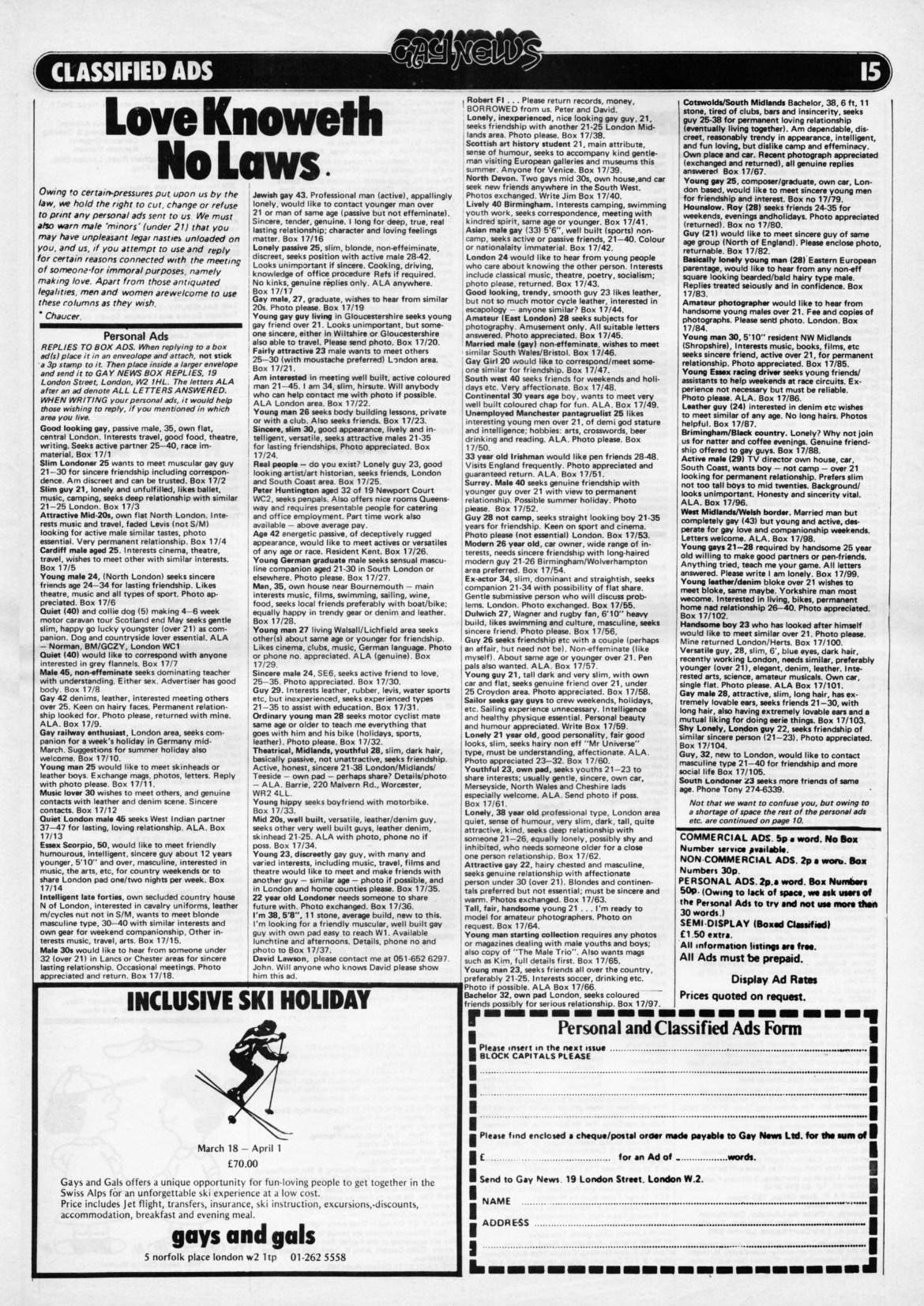

In a study done on a similar queer hookup SNS called Jack’d, Miller describes the online profile as “new media’s version of the personal advertisement.” The personal advertisement, similarly to “subcultural codes” and to a certain extent the cruisers, acts as a way for like minded individuals to find one another through the use of photographs and captions. While personal advertisements existed in print media, SNSs like Grindr use the same principles in the online profile for the mobile hookup generation.

Classified ads from February 21, 1973. Courtesy of the Gay News Archive Project.

In “Bent Passions,” Fred Fejes notes that while queer sexuality and identity don’t exist entirely in a vacuum, they often fall into hegemonic and heterosexual norms. “While some gay males draw upon the texts of identity of female heterosexuality such as represented by drag queens, the dominant mode of incorporation tends to be from heterosexual masculine texts. These are the ones that gay males are most familiar with, being unsuccessfully socialized into heterosexual male roles since birth,” said Fejes. There is the idea that queer men have “failed” at being men, and they turn this rejection from straight society into power within their own marginalized community.

“The [gay] boy then believes that he, intrinsically, is unlovable. He has to change himself in some way in order to actually deserve affection from other people,” said Brendan Yukins, Rape Prevention Educator at Rape Victim Advocates (RVA).

The construction of identity in digital spaces also allows queer men to try out different “masks.” In his study on the upkeep of gay male identities on Grindr, Rusi Jaspal found that Grindr “accentuated the agency that they had in constructing, re-constructing and projecting identity in accordance with context and desire…identities are no longer perceived as ‘fixed’ but rather as mutable and malleable.” Queer men are able to experiment with their sexual identities on queer SNSs through what, and how much, they show on their profiles. One day a user could be wanting casual sex, another day he might just want to chat. The user can frame his profile differently to express different intentions, creating an ever-changing identity.

Grindr, along with other queer SNSs, has levels of anonymity. Specifically on Grindr, there is the practice of “unlocking” pictures. In addition to the photos publicly on one’s profile, a user can also upload private photos to the app and share with certain people at their own discretion. There is an amount of control and power within this practice. A user can show as much of themselves as they want and can tailor their identities for different purposes. Oftentimes the construction of a masculine identity and profile is to gain admiration and social capital in their community. After being ostracised by their families and even society at large for their identities, queer men take their hurt and become mirrors of their oppressors to gain capital and status within their community. “Users strive to gain acceptance and inclusion from others on the application and they present themselves in ways that may enhance these fundamental physiological processes. Even as some individuals leave the application, they acknowledge the consequences of their departure for self-identity,” said Jaspal.

Miller found that more than one in five users had their face absent from their first photo on Jack’d, and that there was a focus on masculinity and physical fitness in their own profiles, as well as the profiles they found desirable. This is where Masc4Masc culture takes form. Where queer men have been ridiculed for feminine behavior and have been deemed as “failing at being men,” they work out, become a man’s-man and take to spaces like Grindr to find power by rejecting those notions and upholding the hegemonic standards of masculinity that was used to oppress them.

“If we accept ourselves for being gay that’s enough,” said Yukins. “As gay people have become more accepted by the mainstream, there is this falling back. If I am independently wealthy and white and I am able to navigate the spaces outside of the gay community with a certain amount of authority and power, I am very reluctant to give up that authority within those gay spaces.”

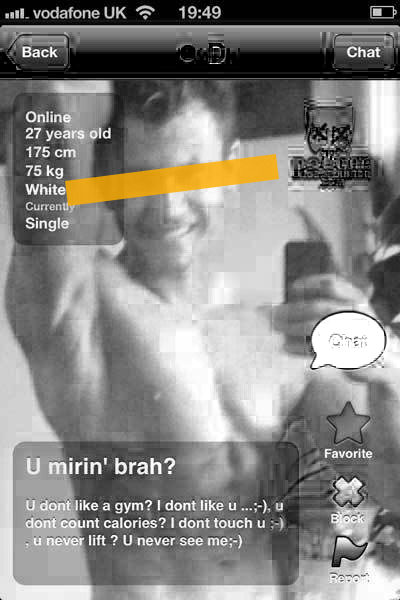

Masculinity as it pertains to gender presentation adapts not just to the hierarchy between men and women, but also between different subsects of men, which can be applied to the intersections of sexuality, race and the physical body. Various labels assigned to and by queer men (“twink,” “bear,” “masc,” etc.) are derived almost entirely from the physical self. In the “body nazi” tag on Douchebags of Grindr, many users stress an importance of physical fitness. One users’ headline boasts “If you don’t work out, WE won’t work out.” Another says, “U don’t like a gym? I don’t like u…;-) u don’t count calories? I don’t touch u ;-), u never lift? U never see me ;-).”

Photo: Douchebags of Grindr.

In Miller’s study of Jack’d, he found that 19 percent of users included a description of their body, fitness level and/or interest in the gym in their profile, and a majority of that percentage included shirtless pictures in their profile. Miller also found that users had an “overwhelming privileging of masculinity.” Out of the 21 men who indicated a preference for masculine or feminine partners, 14 explicitly stated a preference for masculine partners, eight stated not wanting feminine partners, and the remaining user expressed an interest in feminine partners.

“What I see from my perspective is men taking that hurt and wanting to feel appreciated and adored and loved,” said Yukins. “People go to the gym and work on their figure and they’ll become accepted with their physical appearance so when they send that pic, the response they get is ‘oh my god, so hot.’”

There is a very real fear of sexual and romantic rejection in the queer community that stems from rejection from the family or from society. For many queer men, the emphasis on physical fitness and masculinity is a way to receive validation in a way that directly opposes stereotypes and ostracizations associated with male queerness. If a queer man has the body of an Adonis, maybe he’ll finally succeed at being a man, regardless of his queer sexuality.

This masculine ideal in queer male spaces derives from limited media representations of queer bodies, most notably in gay pornography. For many queer men raised in the digital era, gay pornography was their way to experiment with sexuality and find out what it is that they find desirable. Yurkins argues that the representation found in gay pornography is not only limited, but can directly shape the viewer’s sexuality.

“A lot of the gay porn that millennials first secretly saw on their parents computer was extremely narrow,” said Yukins. “It’s not body positive, and it has a very narrow definition of what is an attractive man.”

In many ways, gay pornography is the only source of explicit queer sexuality available, even in contemporary media. Because of this, gay pornography has an immense amount of power in shaping the sexual norms and desires of the queer people who watch it. Fejes argues that heterosexual porn is “generally marginal to the overall construction of heterosexual identity,” whereas for queer men, gay pornography “often serves as an important source for the definition of desire and identity.” Because there is a wider pool of media for straight audiences, porn doesn’t have to be the only example of straight sex or identity. For queer audiences, however, gay pornography becomes the textbook in queer sexuality and queerness as a whole because there are simply no other representations.

Gay porn is aggressive and oftentimes violent, which can be damaging if that is the only accessible example of queer sexual behavior. In porn there is also a focus on the fit, rugged body. While “bears” and other depictions of plus size queer men exist in gay pornography, they are in the vast minority. In a Masc4Masc context, when there are two sexual partners clinging to aggressive standards of masculinity, it can become dangerous in the bedroom.

“Who’s gonna out-masc the other one?” said Yukins. “If I’m trying to out-man somebody, that’s probably going to be super aggressive sex. It’s fine to engage in consensual aggressive sex, but if I start placing something like my masculinity on the line, I guarantee you it’s going to lead to me being less receptive to the word ‘no.’”

It is also important to note the settings and aesthetics in gay pornography, as they tend to uphold rigid definitions of masculinity. In “After Male Sex,” Richard Rambuss argued that “Mainstream gay male porn runs on the desire for masculinity, on an erotic intensification of it.” Many popular gay porn films take place in a gym, or a locker room, or a construction site. (This is also illustrated in depictions of queer sexuality in popular media, like James Patrick Dawson’s photo spread in XY Magazine that shows two straight-appearing jocks cruising in a locker room.) Porn can exist in hundreds if not thousands of subgenres for niche sexualities, but the industry still caters to the least common denominator: rough masculinity sells.

On sexual SNSs, both heterosexual and homosexual, it is impossible to talk about masculinity and physicality without discussing the dick pic. The dick pic is the culmination of sexual power and physicality for cisgender men. In both heterosexual and homosexual contexts, a man sends a dick pic to incite a positive reaction from the recipient. He has a penis, which is revered in both hetersexual and homosexual sexuality, and will use it to position himself as an object of desire.

“A lot of people interpret masculinity on a physical level, like the size of one’s penis,” said Yukins. “The logic behind a dick pic is exactly that performative nature: ‘I have done this thing that people say is gonna make people attracted to me, I have this object. Now I expect you to bow down and worship it.’”

The penis is the physical manifestation of manhood and the performance that goes along with it. As the penis plays a fundamental role in queer male sexuality, there is an immense amount of power given to this phallic indicator of maleness and masculinity.

Graphic by Cody Corrall. Using images by Dev Patel and Alexander Skowalsky.

There has been some pushback against Masc4Masc in the queer community, most notably with the hashtag #Masc4Mascara. #Masc4Mascara is a social media movement heralded by feminine queer men in direct opposition to the body and masculinity standards set by Masc4Masc. While poking fun as the hegemonic norms within the community is rising in popularity, it is by no means the standard, and doesn’t pose a real threat to the dominant Masc4Masc culture.

Many people in the Masc4Masc community ask “what’s the harm?” They believe that their sexual and physical preferences are just that: preferences. But these preferences online help shape beauty standards and determine what is and isn’t desirable offline, which can carry a lot of weight. Oftentimes these preferences put queer men who fit into hegemonic ideals of masculinity – physically fit, aggressive, not feminine – on pedestals, leaving anyone who doesn’t fit into those beauty standards to be seen as less than and undesirable within their own community.

Masc4Masc also erodes at the sanctity of the queer underground space on the Internet. SNSs like Grindr were formed for the same reasons the subcultural codes in New York were formed: to create a safe space for queer men to experiment with sex and sexuality. These spaces were free not only of judgement from society, but also of potential acts of violence of participating in “deviant” sexual behaviors. In the digital world, SNSs come about as judgement free spaces for sexual experimentation. However, because of a culture where gay men learn sex and sexuality from narrow depictions in porn, along with the constant need for validation and respect from the straight people who alienated them – SNSs like Grindr have lost their value in queer society. Spaces where Masc4Masc is rampant are only safe for those who fit into hegemonic standards of masculinity, oftentimes the same standards that demonized queer people for being too feminine and for failing at manhood.

Masc4Masc culture upholds a dangerous set of standards for queer people. Not only does it deem feminine queer men as sexually unworthy, for queer men who are masculine, it establishes expectations of aggression and violence in the bedroom and potentially unhealthy expectations of physical fitness.

“Gay men are hyper sensitive about being accepted or rejected – for very good reasons,” said Yukins. “A lot of them come from very difficult backgrounds where people have rejected them based on their sexuality and have emasculated them within family contexts.”

In Masc4masc culture, “masc” queer men have taken the experimental underground spaces of the web and have established a hierarchy within it: one that benefits those in line with the traditional, physical masculinity used to oppress them and disadvantages those who dare to exist outside of those standards.

Header by Cody Corrall. Using images from Douchebags of Grindr, Dev Patel and Alexander Skowalsky.

'10-Year Challenge' Reveals Shame in the Gay Community - Gayety

11 December

[…] Within our research, we seek to understand and illuminate femmephobic attitudes. For many gay men, Facebook and Instagram and gay-specific dating apps are hotbeds of body image struggles and online gender-based discrimination. […]

Does the 10-year Challenge Reveal Femmephobia in Gay Communities? - #GAYNRD

12 December

[…] Within our research, we seek to understand and illuminate femmephobic attitudes. For many gay men, Facebook and Instagram and gay-specific dating apps are hotbeds of body image struggles and online gender-based discrimination. […]

10-year Challenge reveals femmephobia in gay communities – itransgender

19 December

[…] Within our research, we seek to understand and illuminate femmephobic attitudes. For many gay men, Facebook and Instagram and gay-specific dating apps are hotbeds of body image struggles and online gender-based discrimination. […]

10-year Challenge reveals femmephobia in gay communities – igay

19 December

[…] Within our research, we seek to understand and illuminate femmephobic attitudes. For many gay men, Facebook and Instagram and gay-specific dating apps are hotbeds of body image struggles and online gender-based discrimination. […]

10-year Challenge reveals femmephobia in gay communities – ibisexual

19 December

[…] Within our research, we seek to understand and illuminate femmephobic attitudes. For many gay men, Facebook and Instagram and gay-specific dating apps are hotbeds of body image struggles and online gender-based discrimination. […]

10-year Challenge reveals femmephobia in gay communities – ilesbian

19 December

[…] Within our research, we seek to understand and illuminate femmephobic attitudes. For many gay men, Facebook and Instagram and gay-specific dating apps are hotbeds of body image struggles and online gender-based discrimination. […]