More women today are becoming journalists, but men are still dominating bylines, nightly news and radio shows. According to the Women’s Media Center (WMC), only 25 percent of women work as anchors, field reporters and producers in evening news broadcasts and 38 percent of women make up the print journalism industry. A 2017 survey by the American Society of News Editors found that women make up a little over one-third of newsroom employees overall, about a 1 percent increase over recent years. Although there has been a small increase in female employment in newsrooms across the country, women are still a minority in the newsroom.

The average day for Chicago Sun-Times reporter Rachel Hinton isn’t really average at all. She’s either running around the city council offices or tracking down government documents for whatever story she’s working on. Hinton started at the Sun-Times in summer 2017 and said that she notices gender inequality in her newsroom.

“It looks like one female editor on the news side and none, I believe, in sports,” Hinton said over email. “It looks like editor meetings that are mostly male and mostly white. Overarchingly, it looks like a hole in coverage and in vaguely sexist statements about what women should cover without real evidence to back that up.”

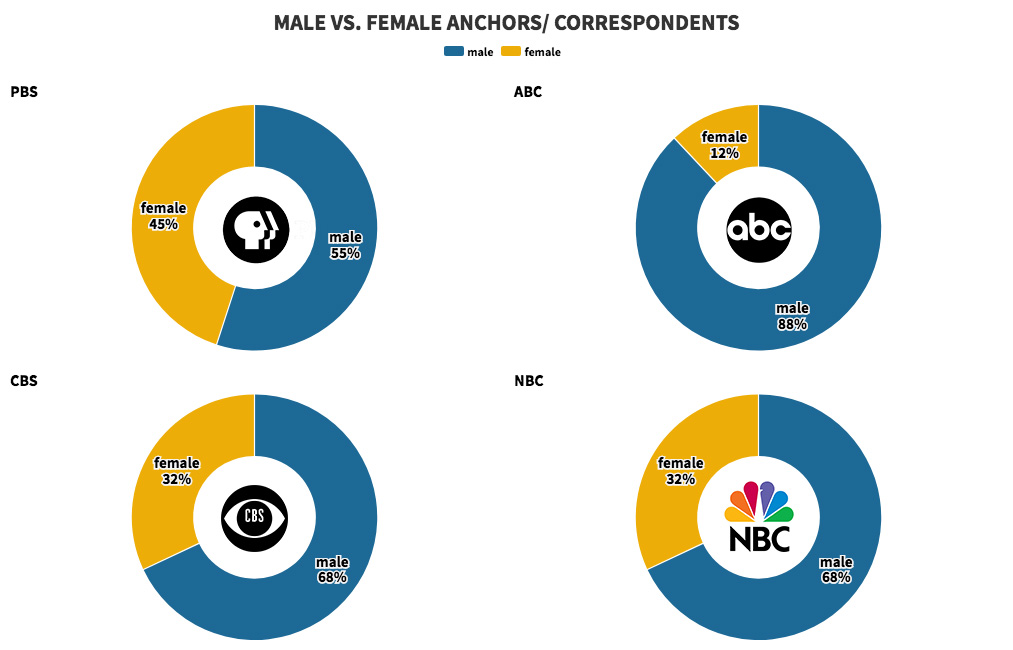

According to a 2017 study done by the WMC, men produce and report about 62 percent of the news while women only produce and report about 38 percent. The WMC found that female employment in newsrooms only improved by 0.03 percent since 2016. This study found that the disparity exists in basically every news medium. Online news, wire services, newspapers and television news are all areas in which women make up a minority. Women appear to be especially a minority in television news. According to the same report by the WMC, women only make up 25 percent of the reporters, anchors and correspondents on ABC, NBC, CBS and PBS.

“I’ve worked as an intern at ABC’s Windy City Live and WGN Morning News and I can tell you that the gender inequality is more apparent in news than in the talk-show industry,” said Diamaris Martino, a reporter at CBS Chicago. “News is still very much an old white man’s game and women are still fighting to get to where they want to be.”

The first issue women seem to face in the newsroom is opportunity. When pitching ideas to newsroom directors, editors and other bosses, women still find themselves left out of the conversation. Television and print journalist Carol Marin, from NBC5 and WTTW Chicago, believes women may be shorted the opportunity to report on “heavier” topics.

“I still think that when you look at who runs newspapers and who runs television or radio stations, it still is a male-dominated world,” Marin said. “There still is the thickness of a glass ceiling for a lot of women and that’s the thing, I think. You know, we see it in Congress. We see it in the fact that this is a country that’s never had a woman president when so many countries all around the world have had prime ministers and presidents who were women. So, I think you have to ask the question culturally about why we’re still hidebound.”

According to the WMC study, women are more likely to report on lifestyle, health and education, whereas men produce and cover mostly sports, crime and justice. In fact, according to the study, out of 853 sports reporters, only 97 of them are women. Out of 2,868 crime and justice reporters, 904 of them are women. Why aren’t women covering topics like the ones men are covering? Some argue that there simply aren’t enough women reporters in that field or women don’t have an interest in those issues, but that’s not entirely true.

Lauren Magiera, WGN’s sports reporter, has been covering this topic since the start of her career.

“I’ve always been a sports reporter and I’m lucky to have this opportunity,” Magiera said. “I feel like women in sports is becoming more popular. Nowadays, it’s odd for a station not to have a woman. It’s great that the opportunities are opening up for women, but at the same time, a station will not likely have more than one woman.”

And it’s not only sports that women are shorted on. Covering politics, foreign affairs and crime are also issues that many female reporters are skimped on the opportunity to cover. Marin remembers a time when she was told she couldn’t cover a story because she is a woman.

“I started as a reporter and an anchor in a newsroom by about 1974,” Marin said. “In those early years, for sure, if I wanted to go, and I did, want to go cover a prison story in Nashville, Tennessee, I remember my news director, a male, saying, ‘Well, you can’t send a woman into a prison.’ That’s obviously changed and changed for the better, this idea that only women can cover certain kinds of things.”

Marin went on to cover that prison story. She interviewed criminals on death row, something many news directors and reporters would have never expected from a woman. From there Marin covered stories on government corruption, crime and other issues that many other women like Marin had to fight for. Martino is also aware of the struggles of pitching and covering specific stories.

“I pitch daily stories on events going on around the city that focused on different things like clothing drives, women empowerment events and events for children,” Martino said. “But whenever I would pitch them they would always get bumped for more ‘serious’ stories. Like shootings, carjackings, murders or thefts. Even when you’re pitching ideas you have to come in with way more background info, possible people to interview and general info than other male counterparts. Women are always trying to prove themselves, but have to do more work to do it.”

Graphic by Natalie Wade, 14 East.

Gender pay gap in the newsroom

Salary is usually the main topic of conversation when talking about gender inequality in the workplace. Women are paid less than men in a majority of positions in the newsroom. A 2016 study done by the Lillian Lodge Kopenhaver Center for the Advancement of Women in Communication found that most of the female workers’ salaries were between $50,001 and $75,000 while men dominated the highest salary bracket of $150,001 and above. Women of color are especially affected in terms of salary and position. About 17 percent of non-white respondents reported that their annual income was between $25,001 and $50,000. Women still make less than the average man earns, even though the study found that more women have some type of college degree.

This trend is not not new. In the ‘70s, women reporters at Newsweek learned that they were being paid an average of $10,000 less than their fellow male reporters although they were producing the same work. The women asked Newsweek for equal pay for equal work, but didn’t end up receiving it until they filed a lawsuit and took Newsweek to court. They later won the case and were paid a fair salary. Almost 50 years later, women reporters are still having the same salary issues at news organization.

Not only are women not paid equally, but they don’t hold equal positions. The 2016 study also found that women are three times less likely than men in communication professions to hold top management positions. It was also found that women in these professions such as journalism, advertising and public relations are more likely than men to feel that they’ve been rejected from receiving a raise or higher position due to their gender, race or ethnicity. Whether women are reporters, producers, editors, news directors or managers, they are still denied opportunities to get paid as much as men do. When trying to advance their careers, women are more likely to be turned down.

“I think it’s still because of the lack of trust in woman reporters,” Martino said. “I watch a lot of Latino news and men are always reporting in foreign countries because executives think it is safer if a man goes. Such as sending a man to report on issues in Saudi Arabia versus sending a woman because a man might get better tips and coverage than a woman.”

Higher positions are usually male-dominated. A 2017 ASNE study found that over 60 percent of newsroom leaders are men. This creates a very generic newsroom that lacks diversity and therefore will lack coverage on specific stories or issues.

“A lack of women in the newsroom definitely hurts coverage and allows things/stories slip past that shouldn’t,” Hinton said over email. “I think women are more aware of sexism/sexist statements than men are or are at least more aware of how something might be taken. I think having a female presence helps balance coverage.”

Even when holding similar positions to men, women’s stories are often dismissed or passed to men. In an episode of Refinery29’s podcast, Strong Opinions Loosely Held, titled “Why Male Bosses Don’t Get It,” the host, Elisa Kreisinger, talks about gender inequality in the newsroom. Kreisinger brings up the issue of pitching ideas and how the majority of stories go to male reporters even though they were pitched by female reporters.

“I pitched an idea to cover a Mariachi band on the West Side that had gotten nominated for a Latin Grammy,” Martino said. “I pitched them for over a month and no one took me seriously until I sat down with a female Latina reporter and pitched her the idea and told her to back me up. We were finally able to get it the coverage it deserves. There’s always power in numbers, especially when you’re a woman and a woman of color.”

Bringing men into the conversation

Kreisinger also talks with men on her podcast, opening the dialogue and exploring how gender inequality that can affect them, too.

NBC5 Chicago producer Don Moseley believes female representation in newsrooms has improved, though gender equality has yet not been entirely achieved. “The hierarchy was male and white and the hierarchy of each television station was by and large male and white,” Moseley said. “If you flash forward today, you can see that it has changed significantly, but the question is, has it changed far enough?”

When talking about gender inequality in the workplace, it is a conversation that is dominated by women. Men are usually not ones to speak on this subject.

“I don’t think they’re reluctant to speak on this,” Martino said. “It’s more that they are uninformed and sort of blind that it’s even a problem. Because a lot of men who are in the industry have been here for some time and they were originally surrounded by only men, then they got one or two women and think the problems fixed, but it’s not.”

For decades, gender inequality has seemed to be an issue that has been, and still is, largely ignored. Many women are afraid to bring up unfair practices in the workplace for fear of losing their job or being seen as “hard to work with.” Gender inequality is a “no problem” problem, as law professor Deborah L. Rhode puts it. In her book, Rhode explains the “no problem” problem as a gender inequality obstacle in the workforce that people assume has been solved. Therefore, many people, especially men that aren’t affected by gender inequality, don’t notice the issues and continue as if there isn’t a problem, or see it as a “women’s problem.” Rhode wrote in her book that many believe that “time will take care of the problem” and if women will just “concentrate on the job and get the chip off their shoulders…they should do just fine in today’s society.”

As women are working toward achieving an equal playing field in the newsroom, many believe that having their male counterparts behind them will provide greater progress. Hinton believes it’s hard for some men to join the cause when they do not realize there is a problem facing women in the industry.

“It’s hard to speak out or even recognize something when it benefits you,” said Hinton. “They may see women in the newsroom as progress, but may not see that there are still a lot of things women are dealing with just to be taken seriously/given the same opportunities they are. I think fear of speaking out comes from being in a well-represented majority and being afraid of having the rest of that majority turn on you.”

Header by Natalie Wade, 14 East.

NO COMMENT