What happens when stories of female horror are rarely told by women?

Jamie Lee Curtis is having her cake and eating it, too. Halloween, the much-anticipated sequel to John Carpenter’s 1978 classic, has quickly become the most profitable successor in the franchise. Curtis boasted on Twitter about Halloween’s $77.5 million opening weekend making it the largest horror film opening with a female lead, the largest film opening with a female lead over 55, the second-largest October film opening of all time and the largest Halloween opening of all time. It’s also the highest-rated sequel in the Halloween franchise — a breath of fresh air for die-hard fans who have been disappointed time and time again with lackluster reimaginings.

The box office success of Halloween is a huge accomplishment for women in the horror genre. But it has also raised questions about how much that accomplishment is worth when the film is still directed, written and produced by men.

Halloween sees Curtis back in her iconic role as Laurie Strode four decades after narrowly escaping the murderous rampage of Michael Myers. Strode prays for the day that Meyers escapes from prison so she can have a revenge of her own making and avenge those who were not as lucky as her. Strode is questioned for her over-preparedness, her rigorous training and laughed off as a tinfoil-hat-wearing-nut. But in spite of that, Halloween manages to be a woman-centered story that deals with the often-lost repercussions of horror like living with trauma and grief.

While it’s heralded as a woman’s story, it’s one that is ultimately told by the men who still dominate the film’s production. In an interview with Polygon, Jason Blum of Blumhouse Productions admitted that he has never produced a theatrical horror release directed by a woman. Blumhouse is the studio behind many of the best low-budget horror films of the last decade. From Paranormal Activity to Insidious, The Purge, Creep, Get Out and now Halloween, Blumhouse has dozens of highly acclaimed horror films under its belt — all of which are directed by men.

Blum said this wasn’t for lack of trying — he cited several attempts of working with Babadook director Jennifer Kent and Honeymoon director Leigh Janiak to no avail.

“There are not a lot of female directors period,” Blum told Polygon, “and even less who are inclined to do horror.”

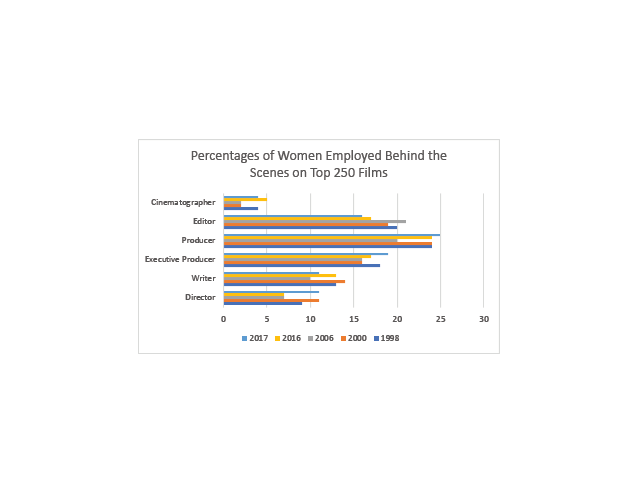

The idea that there are not a lot of women directors is a misconception. Yes, women only accounted for 11 percent of directors of the top 250 films of 2017. And yes, out of the top 1,100 grossing films in the last decade, women accounted for 4.3 percent of directors. But this is not because women don’t want to be directors – it’s because there are so many obstacles in the way for them to actually become directors. And without experience or capital to navigate the industry, women are less likely to be hired for large productions — leaving women’s narratives on the cutting room floor.

Graphic by Natalie Wade, 14 East.

But Blumhouse isn’t foreign to taking risks on directors who might have less experience in the genre. Get Out was Jordan Peele’s first foray into horror and Halloween was the first for director David Gordon Green. So when Blum says it’s hard to find women who are interested in directing horror, it feels empty and wholly misinformed. Despite Blumhouse’s inclination to take risks and provide a platform for new directors, it is becoming clear that the standards for women directors might be higher than those for men and that horror films directed by women are considered more of a gamble for studios.

Blum has since issued a statement on Twitter, calling his remarks “dumb” and “a stupid mistake.”

“We have not done a good enough job working with female directors and it is not because they don’t exist,” said Blum. “I heard from many today. The way my passion came out was dumb. And for that I am sorry.”

While Blum has acknowledged his flawed but “passionate” thinking, this same thinking is held by many male producers and executives who control the industry. This is by no means the first time women have been questioned by powerful men about their place in horror.

In May 2010, American Psycho author and co-screenwriter Bret Easton Ellis told Moviewire that he wasn’t “totally convinced” women could direct horror movies. The film adaptation of the satirization of male power, greed and violence is famously directed and co-written by Mary Harron. When asked about his thoughts on Harron as a director, he said, “There’s something about the medium of film itself that I think requires the male gaze.”

Ellis claimed that women were “trapped’ by their emotions, making them unable to create films that are neutral and can appeal to all audiences the same way men can.

When Ellis talks about the “male gaze,” he’s referencing — inadvertently or not — a bastardized interpretation of Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” To Mulvey, feminist film scholar, the gaze is something that men get to do to women in cinema. Men look at women and women are on the receiving end of those looks. They’re objects of male desire or, more likely, fetishization.

But the gaze is not just limited to those onscreen. Mulvey claimed that the gaze can be instilled by the audience, the director, even the camera can have a gaze. Mulvey thought narrative films were constructed around the pleasure of men because classical Hollywood was structured by a “patriarchal unconscious,” so every part of the filmmaking process was inherently tied to fulfilling a male gaze.

Audiences tend to share the gaze of the protagonist, who is often a man, and gaze upon the women in the film as a kind of spectacle. Living in a patriarchal world has side effects, and how the world views and consumes the bodies of women is one that is extremely pervasive. In horror this is especially true as women are often the spark of supernatural or horrifying moments and become a literal spectacle rather than just a symbolic one.

“We’re watching, and we’re aroused by looking,” Ellis told Moviewire. “Whereas I don’t think women respond that way to films, just because of how they’re built.”

Women’s bodies and narratives have been fundamental to horror since the inception of the genre. The emotions and sexuality of teenage girls are the catalyst for many horror plot points, and the genre would be far more limited without women as plot devices. But it’s rare when stories of horror are told from the perspectives of women.

Women have directed many successful horror films of the last century — from Ida Lupino’s The Hitch-Hiker in 1953 to Amy Holden Jones’ Slumber Party Massacre in 1982 to Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin in 2011 to Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night in 2014 to Julia DuCournau’s Raw and Anna Biller’s The Love Witch in 2016.

There isn’t a lack of women directors in the horror genre as Blum suggested. Cut-Throat Women is a growing database of women involved in the production of horror films: directors, producers, screenwriters and organizers of film festivals. The database currently lists over 650 women directors who are actively working in the genre.

This isn’t to say that men aren’t allowed to direct horror, or even horror films that are led by women. There’s a cyclical problem that makes women not have the same opportunities in a genre that is supposed to be bursting at the seams with opportunity due to its humble, do-it-yourself sensibilities. If men in the industry don’t believe women can direct horror, then women don’t have experience or trust to be hired to direct large productions, then women try to navigate the system independently, then producers take a chance on a man to direct the film anyway — and the cycle continues.

There are women who are interested in horror, there are women directing horror movies or waiting for the opportunity to do so. What the genre needs more than anything is to take more risks to lift up the voices of women in the industry. Women are already the backbone of the genre’s basic narrative structure, one that commodifies their bodies for brutal imagery — there’s no reason women should be barred from reinventing these stories in their own ways or from their own individualized experiences.

Header illustration by Jenni Holtz, 14 East.

NO COMMENT