Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s press secretary from Chicago shared his special experiences with the iconic civil rights leader.

“Great sadness. Great sadness,” said Don Rose when asked how he felt about the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

Rose, 88 years old, was King’s speechwriter and general political guru.

He had been writing speeches professionally for six to eight years before that, but when it came to writing them for King, “the task reduced me to a puddle of anxiety,” Rose wrote in his piece “Speech Writer’s Soul Sent Roaring” that he shared with me during our correspondence. “Here was one of the great orators of the 20th century — possibly of all time. Here was a Nobel Prize laureate. Here was a Baptist preacher, steeped in the black oral of tradition.”

“Even his conversations sounded like presidential addresses,” Rose said.

As Rose sat within the commotion of the lobby of the Art Institute of Chicago the afternoon I interviewed him, he said, “We have so many more problems now, he would be working on them. We would’ve had to develop new tactics; he would’ve had to become more political. You know — it’s a much more complex society now.”

Don Rose. (Bella Michaels, 14 East)

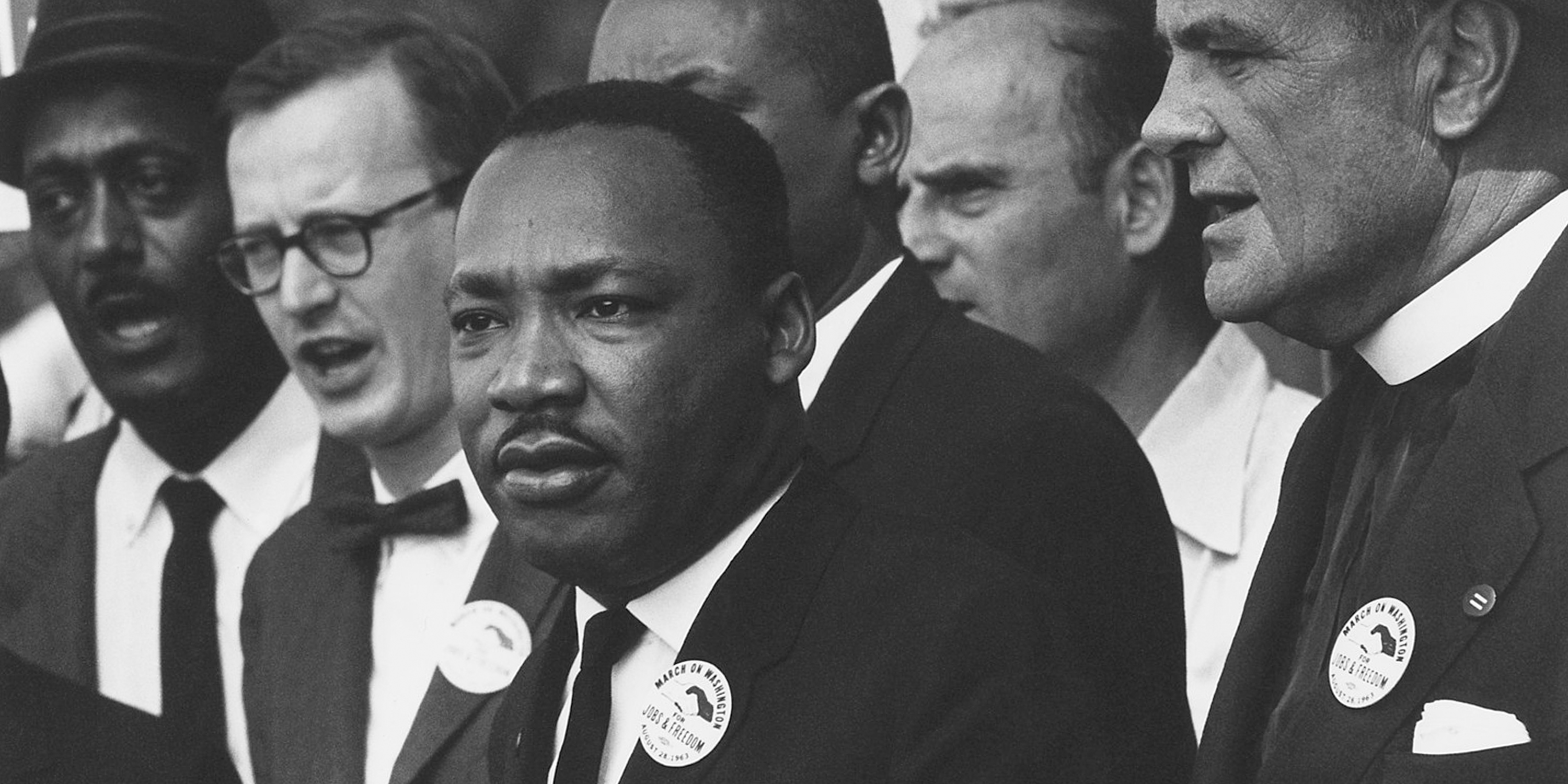

Rose is a veteran Chicago journalist and social activist from Rogers Park, Illinois. During the 1960s, he was active in the civil rights movement. He was the Midwest States organizer for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

He later served as the press secretary to King during his Chicago campaign.

“Oh it was an amazing experience — getting to know him and doing the work,” Rose said. “I had been active in civil rights before he arrived and I was working with a group when he came to Chicago. They merged the group that I was working with, with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and I had been the press secretary for the group before that, it was called the Coordinating Council for Community Organizations.”

King led the Freedom Movement in Chicago from 1965 to 1967, which included a large rally, marches and demands regarding the city of Chicago’s systematic racial discrimination and segregation in housing.

Chicago was known as the most segregated city in America. Dr. King worked for equity and fair housing in response to the redlining and strategically-located highways that kept the city divided. This movement is credited as the inspiration of the Fair Housing Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 1968 just seven days after King’s assassination.

While Rose worked on his speeches, he kept in mind that King wanted to avoid the denunciations of Mayor Richard J. Daley that other political and civil rights leaders that Rose wrote for had previously commended.

When it was time for King to deliver his speech at the Freedom Movement in Chicago that Rose wrote for him, he began with the first page and left the text halfway through. “I was crushed,” Rose wrote in “Speech Writer’s Soul Sent Roaring.” “A reporter looked over at me with a question on his face — obviously concerned that the text was not what King was delivering.”

A familiar sentence came forth.

King improvised and went down his own path and then concluded with Rose’s words.

“Adding flourishes, filigree, arpeggios and angelic harmonies,” said Rose when describing how King sounded to him when he trailed away from his text. “I never sounded so good.”

Although King was admired and idolized in African-American communities, Rose got reports from organizers saying that some Black areas raised questions about a Southern preacher that was being sanctified.

“Dr. King was well covered by media here. A news conference, a speech, whatever, needed no gimmicks or stunts to get a full turnout of local and national reporters and cameras,” said Rose. “Only twice did I resort to stunts.”

Rose’s pal, Al Raby, was a pool player and he had a regulation table in his living room. “I thought the idea of a pool game in the heart of the ghetto might serve the purpose,” said Rose. “Al asked the good reverend if he ever shot pool and the reverend replied that he loved the game, having honed his skills during college days.”

“We thought it would be helpful to humanize him, make him more of a ‘street’ guy,” Rose said.

The stunt worked. The media loved it, and for days Rose said he heard reports of a new admiration of King.

If King were still alive, how would he react to society today?

“Well, I think he would pick up on where he was at the time he was murdered by moving into economics and he certainly wouldn’t be opposed to working against the administration we have now,” Rose said. “But he would continue to fight for poor people. We didn’t have the term economic inequality at the time in the ‘60s when we were together. I think he would be working on that issue, as well as the continuing fight for civil rights.”

King was a strong and peaceful visionary who enforced his dream through action and nonviolent protest — a dream that lives on in the minds of countless Americans generations later.

At the 1963 March on Washington, King delivered his soul-stirring ‘I Have a Dream’ speech that remains as one of the most prominent speeches across the globe, inspiring individuals of all backgrounds. When asked what her “MLK dream” was, Kathy Given, 48, said, “I’m from West Virginia and there’s still a tremendous amount of poverty there. I’m a teacher and we just had a huge strike. Our working people don’t make the money that they need to make to live. I believe that racial inequality is worse because the middle class is driven down and people don’t care about anything but themselves because everybody’s scrapping to make it.”

An MLK dream doesn’t necessarily mean one has to go out and protest. It can be as simple as spreading more love.

Sixty-six-year-old Barb Patten said, “My MLK dream is that I would like to get rid of all this hate — and you know what? I like the word despise better, because hate, you have to know someone to hate them. These hatreds are coming from despising what they think — not what they know.”

“I want to make the world a better place, which is a very typical type of thing to say,” said Jesse Balluff, 22, of his MLK dream, “but in a sense to just make everyone happy or do the right thing for people that I run into day to day.”

As for Rose, he lived the dream alongside King, one of the most influential figures in history, and assisted him in leaving his imprint to create a more civil society.

Header image by Rowland Scherman; restored by Adam Cuerden

NO COMMENT