On February 11, a street sign named Ida B. Wells Drive was resurrected in Chicago.

Named after civil rights activist and investigative journalist Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, the sign signifies a step in the reframing of political history to honor the accomplishments of those too often overlooked in public American canonization.

The new street name replaces the stretch previously known as Congress Parkway and runs from Columbus Drive to its merger with the Eisenhower Expressway. It marks the first street in Chicago’s Loop named after a woman of color.

The official sign switch took place roughly six months after the name change was approved by City Council in July of 2018. The decision to rename Congress was agreed on after the original proposal of Balbo Drive — named after the Italian Air Force Marshall who made the first transatlantic crossing from Rome to Chicago but also supported fascist leader Mussolini — drew backlash from the city’s Italian-American community.

The renaming follows a national trend to rename public spaces and resurrect monuments dedicated towards influential women in history. New York City will soon receive statues of suffragettes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Richmond, Virginia, will receive a “Voices from the Garden” monument to honor historic women who helped shape the state.

The city of Chicago only has two statues of Black women in its parks — one of former-state poet laureate Gwendolyn Brooks in North Kenwood Park unveiled in June 2018 and one of Georgiana Rose Simpson, the first women of color to graduate from University of Chicago, located in the university’s student center. Wells will also join the busts of Brooks and Simpson with her own statue, located in the historic Bronzeville neighborhood where she lived, worked and raised her family from 1919 through 1930.

While Wells’s most recent honor remembers her time in Chicago, her story starts down the Mississippi to an Antebellum South in transition and a tenacious Black woman willing to write the narrative for reform.

Holly Springs, Mississippi

Ida Bell Wells was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862, to Jim and Elizabeth Wells, just over a year after the start of the Civil War and a year before Emancipation. Her parents, who had been slaves, remarried after being emancipated; her father went on to be a carpenter and her mother a cook. Jim, a member of the political society the Loyal League, stressed the importance of education to their eight children. In 1866 The Freedmen’s Aid — which helped found more than 500 schools for freedmen in the South — established Shaw University, now known as Rust College, in Holly Springs, which Wells attended at a young age.

“Life became a reality” for Wells when both her parents and youngest brother Stanley died of yellow fever in 1876, she wrote in her autobiography Crusade for Justice, edited and published posthumously by her daughter Alfreda Duster. At age 14 she became the sole caretaker for her six remaining younger siblings and became a schoolteacher to support the family. She soon moved the family to Memphis to stay with their aunt and worked at a nearby county school. To get to the school she commuted by train, and even though Jim Crow laws were not yet established race segregation was still enforced on rail lines.

On May 4, 1884, she was approached by a conductor who demanded she switch cars to which she refused. The conductor then turned physical.

“He tried to drag me out of the seat,” wrote Wells, “But the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand.”

After being forcefully removed from the car, Wells filed a lawsuit against the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad and won in circuit court. Though the case was reversed in the state’s supreme court, it marked the first case a plaintiff of color appealed to a state court since the repeal of the Civil Rights Bill of 1875 in 1883.

Still stubborn and ever-determined, Wells soon accepted a teaching job in Memphis which provided better pay and increased access to the city’s vibrant Black community. There, she joined a lyceum composed of other academics where she read copies of the Evening Star, a daily afternoon newspaper based in Washington D.C. She soon took over as editor of the Star from her home in Memphis before being offered a writing position with the weekly newspaper The Living Way, where she spoke out against Jim Crow laws under the pen name “Iola” — like Ida but stretch apart the “d.”

In 1889, Wells was invited to write for the Free Speech and Headlight, a Memphis-based newspaper owned by Reverend Taylor Nightingale and J.L. Fleming. But, Wells wanted more.

“Since the appetite grows for what it feeds on,” she wrote, “The desire came to own a paper.”

So, Wells bought one-third interest and became a partner and the paper’s primary editor.

The business move spurred one career but ended another. In 1891, while still a public school teacher, she wrote a column criticizing the inadequate conditions and poor teaching at colored schools, for which she lost her teaching job. “I thought it was right to strike a blow against a glaring evil and I did not regret it,” Wells said. As always, she continued to look forward and turned toward writing.

During her time with the Free Speech she wrote on civil rights, politics and injustice against people of color. She also wasn’t one to hold punches — she criticized other Black figures of the period, like politician Isaiah Montgomery for his supporting of the “grandfather clause” at the Mississippi Convention of 1890 and activist Booker T. Washington for his criticism of Southern preachers in the Christian Registrar. Her columns made her some friends and some enemies, but they also established Wells as a respected voice.

Memphis, Tennessee

In South Memphis there lived Thomas Moss. Moss, a Black entrepreneur and family man — of who Wells was the godmother of his daughter Maurine — owned the local People’s Grocery Company with Calvin McDowell and Henry Stewart in a section of town known as “The Curve.” Across the street was another competing white grocer, William Barrett.

On a March afternoon in 1892, a young Black boy and young white boy were playing a game of marbles when a fight broke out between the boys. The fight grew to include grown men of both races, ending with a threat from Barrett to seek revenge on the competing grocery store. That Saturday, the men came and another brawl ensued at People’s Grocery, ending in shots fired at the white trespassers and the subsequent arrest of Moss, McDowell and Stewart.

On March 9, 1892, while the men were kept in what Wells described as a “modern Bastille,” 75 masked men took the men from their cells, drove them to a nearby rail yard and shot the store owners to death. Moss’s last recorded words were, “Tell my people to go West, there is no justice for them here.”

Stoked by sensationalism from the city’s newspapers, racial prejudice in the South deepened. Of the lynchings, Wells wrote in the Free Speech, “The city of Memphis has demonstrated that neither character nor standing avails the Negro [sic] if he dares to protect himself against the white man or become his rival.”

Wells (left) wtih Maurine Moss, wife of Thomas Moss, and children. Taken in Indianapolis, Indiana, after the lynching in Memphis. Photo taken from The University of Chicago Guide to the Ida B. Wells Papers 1884-1976.

The murders propelled Wells to a three-month investigation of the lynching, traveling throughout the South to research, report on and humanize over 700 lynchings from the decade. According to the Equal Justice Initiative 2015 “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror” report, roughly 4,075 African Americans were lynched in 12 southern states from 1877 to 1950. A follow-up report in 2017 included Illinois as one of eight states where acts of racial violence were most common.

Again, her criticism drew ire from white southerners. On May 27, 1892, while she was on travel in New York City, she received notice from a New York Sun article stating that the Free Speech had been destroyed and white residents of Memphis threatened that anyone republishing the paper would be punished by death. But rather than responding with shock, Wells had expected the reaction and seemed rather to welcome it as evidence of her writings’ impact.

“I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap,” she wrote. “I felt that if I could take one lyncher with me, this would even up the score a little bit.”

New York, New York

The event solidified Wells’ decision to move East, and with the bat of a lash she began writing for the New York Age, a weekly Black newspaper. Much of her journalism was a revising of racial violence reporting by white newspaper counterparts, exposing their falsities and talking to communities the mainstream media overlooked: African Americans. Her articles were often reprinted, running in more than 200 historically African-American weeklies in the United States and well as papers abroad. Her reporting and analyses garnered the attention of abolitionist and civil rights activist Frederick Douglass, garnering a friendship that lasted until his death in 1895.

After the Free Speech was destroyed, with the support of New York residents Victoria Earle Matthews and Maritcha Lyons, Wells composed a pamphlet on her research on lynching titled Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, which centered on the People’s Grocery lynching then expanded to speak largely of violence under Jim Crow. On October 5, 1892, at the Lyric Hall in New York City, she read the pamphlet in front of a committee of 250 Black women from across the East Coast. As she addressed the committee, she began to break down:

“As I described the cause of the trouble at home and my mind went back to the scenes of the struggle, to the thought of the friends who were scattered throughout the country, a feeling of loneliness and homesickness for the days and the friends that were gone came over me and I felt the tears coming.”

The event propelled Wells’ public speaking career for an array of white, women and abolitionist audiences. In New York she met Catherine Impey, a Quaker abolitionist who published the journal Anti-Caste, and was invited to England for a speaking tour in 1893 and again in 1894.

Wells expanded her research on lynching with Red Records: Alleged Causes of Lynchings, a 100-page follow-up pamphlet to Southern Horrors, published in 1895. It was here that she contested the mainstream media’s depiction of lynching victims as criminals. She became vocal of the hypocritical nature of justifying lynchings on the grounds of sexual assault claims of Black men towards white women — even though white men were and had been sexually assaulting Black women without repercussion for decades.

The book’s second chapter, “Lynch Law Statistics,” includes a breakdown of lynching statistics from 1893 gathered from the Chicago Tribune, separated by cause of death while also naming — and therefore recognizing and calling attention to — the victims.

“She was one of the first people to actually tally the number of lynchings that were happening,” Nikole Hannah-Jones, a The New York Times reporter who co-founded the Ida B Wells Society for Investigative Reporting, told The Guardian. “We like to say she was one of our early data reporters. She began to collect data on this to show how actually vast the scope of the problem was.”

Her public speaking and highly circulated pamphlets put her in the eyes of the British and American public and took her from the writer behind the scenes to front-page news. She was slandered by major white presses, including The New York Times, who referred to Wells as “slanderous and nasty-nasty-minded.” Just last year the paper published its first obituary to Wells.

Chicago, Illinois

In 1893, Douglass, Wells and other activists protested the lack of African-American representation at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Together they printed The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition, which included “facts concerning the oppression put upon the colored people in this land of the free and home of the brave,” according to Wells. The pamphlet, which included a foreword written in English, French and German, found its way into the hands of over 20,000 attendees.

It was with this work she met her future husband Ferdinand Barnett, a well-known attorney and founder of the Chicago Conservator, the city’s first Black newspaper, which Wells soon began writing for. She decided to remain in Chicago and called the city home for the remainder of her active life.

Before leaving for her second tour of England, Wells was also offered a writing position at the Daily Inter-Ocean in 1894, a Republican newspaper in Chicago and the only major white paper to denounce lynching. Wells accepted, making her the first paid African-American woman correspondent to be published in a mainstream white newspaper. “One journal in the United States was brave enough to print at length the doings, impressions, and reactions of a colored woman who was in another country pleading for justice in her own,” Wells wrote of the Daily Inter-Ocean.

In 1917 she also wrote a series of reports on the East St. Louis Race Riots, where over a three-day span white residents slaughtered a reported 39 Black workers in labor- and race-related violence, though the death toll is estimated to be 100 or more (Wells cites the number to be 150 in her autobiography). Wells traveled to the southern Illinois town during the aftermath of the riots.Her accounts of the lives of the town’s Black residents, her criticism of white newspaper coverage and her appeal to Congress were published with the Chicago Defender, which is still in print today.

Wells married Barnett on June 27, 1895, at Bethel M.E. Church on the corner of Dearborn and 30th Street, with a wedding so celebrated it was featured on the front page of The New York Times.

Screenshot of The New York Times front page feature on Wells’ wedding, which ran on Friday, June 28, 1895.

“The interest of the public in the affair seemed to be so great that not only was the church filled to overflowing, but the streets surrounding the church were so packed with humanity that it was almost impossible for the carriage bearing the wedding bridal party to reach the church door,” Ms. Wells wrote.

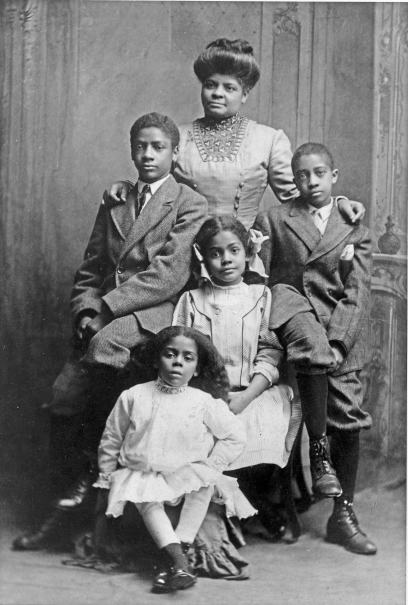

She chose to hyphenate her last name to Wells-Barnett instead of completely taking her husband’s surname, an uncommon decision at the time. Together, they had four children of their own: Charles, Herman, Ida and Alfreda. Barnett, a widower, also had two children, Ferdinand and Albert, from his first marriage. Their marriage was a union of like-minded civil rights activism and journalistic endeavors, such as their work with Chicago Conservator.

While never outwardly labeling herself as a feminist, Wells’ suffragette work focused on equal rights, violence and African-American representation. She was active in the woman’s club movement, a Progressive Era social and political movement started by white, middle-class Protestant women and later adopted by Black women. She organized The Women’s Era Club, the first African-American women’s club in Chicago — later renamed the Ida B. Wells Club. She was openly critical of the exclusive nature of her white suffragette counterparts, best exemplified in her feud with Frances Willard, first President of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. She admonished Willard in a chapter of Red Record titled “Miss Willard’s Attitude,” where she highlights the leader’s distasteful rhetoric towards violence in the South. During Willard’s time with the union, no Black women were admitted to the group’s Southern chapter.

Wells with her children, 1901. Photo taken from The University of Chicago Library digitized Guide to the Ida B. Wells Paper 1884-1976.

During the 1913 National American Woman Suffrage Association parade in Washington D.C. — the harbinger of the modern Women’s March that advocated for universal suffrage — Wells and other African-American suffragists were separated from their states’ delegation and instead told to walk at the end of the parade. Characteristically, Wells refused to do so, instead hiding in the crowd near the Illinois delegates and joining their block once the walk commenced.

A former school teacher, Wells also fought for equality in public education. In 1900 she was so enraged with a Chicago Tribune article advocating for a segregated public school system that she gave the paper’s editor in chief, Robert W. Patterson, a personal visit. “We had quite a chat,” she wrote, “In which he let me see that his idea on the subject of racial equality coincided with those of the white people of the South.” She enlisted the help of Jane Addams and successfully protested against the plan.

Wells also helped form the Alpha Suffrage Club to further African-American women’s involvement in politics. In 1930 she ran as an independent for Illinois State Senate — paving the way for women like current majority leader Kimberly A. Lightford (D). She also campaigned for and helped elect Chicago’s first Black alderman, Oscar Stanton De Priest, in 1914. Those to follow include mayoral candidate Toni Preckwinkle, previously alderman of the 4th Ward. Preckwinkle is a mayoral runoff candidate alongside Lori Lightfoot, another powerful Black woman in Chicago politics. On April 2, 2019, Chicago will vote to elect its first Black woman as mayor.

Portrait of Ida B. Wells at age 68. Photo taken from Crusaders of Justice.

A Legacy of Truth

Wells died of kidney failure on March 25, 1931, at 68 years old. She is buried in Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago’s Greater Grand Crossing neighborhood alongside Barnett, with a shared headstone engraved Crusaders for Justice.

Her crusade is remembered with an abundance of accolades, including most recently the newly mantled street signs, still untainted by the city’s winter sludge. Her journalism is remembered with awards dedicated in her name by the National Association of Black Journalists, the Investigative Fund and Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. The Ida B. Wells Memorial Foundation and the Ida B. Wells Museum in Holly Springs, Mississippi, have been founded in her honor.

In 1941 the Public Works Administration built the Ida B. Wells Homes, Chicago’s oldest African-American public housing development located in the Bronzeville neighborhood where Wells resided. The public housing — built when federal housing policy permitted racial segregation — once flourished to house over 13,000 residents, but by the early 2000s was withering with increasing drug dealing and violence. In 2008, in an effort to reinvigorate the neighborhood and make way for mixed-income developments and private-market vouchers as part of the city’s controversial $1.6 billion housing plan, the buildings were demolished. Residents were forced to relocate, on their own time and dime. Only 348 of the 3,5000 demolished units have been rebuilt, according to a 2017 South Side Weekly investigation.

In 1988 Wells was inducted into both the National Women’s Hall of Fame and the Chicago Women’s Hall of Fame. Her Bronzeville home — located at 3624 S. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive — became a Chicago landmark in 1995. Wells was also inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame in 2011. At DePaul, the Center for Black Diaspora offers an Ida B. Wells Postdoctoral Fellowship dedicated to her civil rights and social justice activism.

Wells also set out to write her own legacy by beginning an autobiography, published posthumously by her daughter Alfreda Duster. Duster pays homage to her mother in the book’s introduction:

“The most remarkable thing about Ida B. Wells-Barnett is not that she fought lynching and other forms of barbarianism [sic]. It is rather that she fought a lonely and almost single-handed fight, with the single-mindedness of a crusader, long before men or women of any race entered the arena…”

As Wells worked to revise American history during her time, so does the city in which she helped shape work to revise its narrative. The influence of Ida Bell Wells-Barnett permeates through her reform and reportage, the paper scraps of her republished writing, the spreadsheets of investigative journalism, the women of Congress and in the streets of Chicago.

Header image by Natalie Wade

NO COMMENT