As a little kid, I can remember watching TV and seeing commercials for restaurants or frozen dinners and the food being advertised as “just how your mama makes it.” I was always sort of confused — didn’t they know my dad made dinner?

Throughout my early childhood I didn’t really understand the terms “housewife” or “soccer mom.” I heard jokes about minivans being “mom cars,” but it was my dad who toted us to sports practice in ours. Was it still a “mom car?”

Teachers in elementary school would always give us handouts for PTA events or forms to be signed and tell us to give them right to our mommies as soon as we got home. These people! It was my dad who would be home at 3 p.m., not my mom — what did they not understand about that?

My mom would be home a little later, around 7 or 7:30 p.m., probably just in time for dinner — we liked to wait for her. She’d be tired and probably still have some computer work to do and she would need to go to bed early to get back up at 5 a.m.

My mom owned and still owns her own small business, where she usually works between eight and twelve hours a day, six days a week. My dad worked, too — he had a couple of different part-time jobs and helped run my mom’s business for a few years.

My mom was what one might call the “breadwinner.” My dad’s schedule was more flexible and arranged around taking care of my sister and I in the day-to-day sense: making us breakfast, taking us to school, picking us up, etc. When we were old enough to stay home alone after school he worked a bit more but, most of the time, we could count on my dad being home well before sunset.

Although I definitely recognized my family’s arrangement as “different” from a young age — I lived in the kind of well-off suburb where PTA moms got more news coverage than our town council — it wasn’t until my early adolescence that I realized this was “gender-role reversal,” a part of this larger sociological phenomenon and not just “my life.”

According to a 2013 study by the Pew Research Center, a record 40 percent of women with children under 18 were also the primary breadwinners in their households, a number that has jumped from just 11 percent in 1960. This number includes a lot of single moms but there are a substantial amount of married women in that figure as well. According to the same study, the employment rate of married women with children was at 65 percent in 2011, a jump from 37 percent in 1968.

The older I got, the more I came to be proud of the fact that my mom — the woman I looked up to most — was a part of this movement. I thought it was this incredible feat of strength, the fact that my mom could get up before the sun rose and get home after it set and tote around her body weight in paperwork and answer what seemed like a million emails in a day and still have the time to ask my sister and I about our days. To help us with our math homework, to hug us goodnight, to bake cookies and watch movies with us on weekends.

To hold me when I cried about bullies at school, about failed tests, about my first breakup.

She came home from what were, 50, 60, even 70 hour work weeks and still get up on Saturday morning to come to our soccer games. She’d wait up for me until I got home by my curfew every Friday night of my senior year if I went out with my friends.

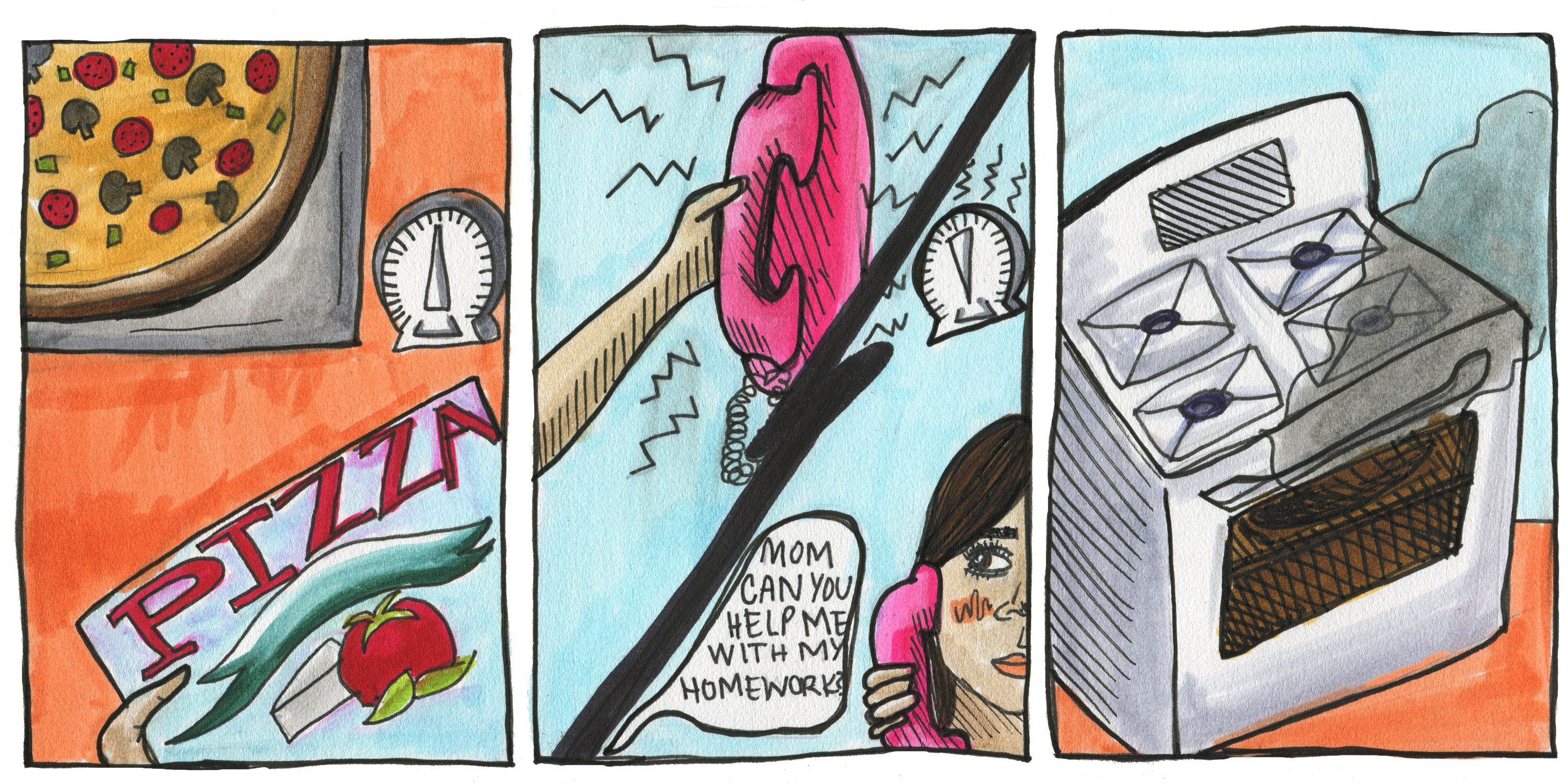

She did so much. I couldn’t possibly complain that the only thing she ever really cooked for us was DiGiorno’s frozen pizza in the oven, burned to a blackened crisp. I loved her for it.

I thought she held the world on her shoulders and that I should, too.

I thought, “this is what a grown woman looks like.” She puts all of herself into everything she does, into everyone she knows. Every moment of her day has to be so full of purpose. If she’s not working she’s helping someone she loves, she’s running an errand, doing something that’s going to support the people around her.

To give the world so much of yourself is an incredible feat of strength. One that I later realized often leaves you with nothing left for yourself.

There were moments that, in retrospect, my mom broke. There were a few moments here and there as a child where I could hear her sobbing when she thought I was asleep. Times where I can remember seeing tears on her face, the light of her computer screen illuminating them as they rolled down her cheeks.

“What’s wrong, mom? Are you okay?”

“Don’t worry, I’m just tired.”

Tired, I now know, is an understatement.

This past year, I, too, tried to put the world on my shoulders. It was my first time living in my own apartment. I was turning 20 and I felt, for the first time, like a real grown up. A real woman, doing a lot of real woman things, all at once. I had a part-time job while being in school full-time. I was pushing myself to publish a lot more. If I wasn’t doing those things, I was going out with an expanding group of friends, hanging out with my long-term boyfriend or keeping in touch with my family back home on top of managing the everyday aspects of living on my own for the first time: grocery shopping, paying bills, cleaning. I ran almost every day before class. I worked every day on almost every weekend.

I was doing all of these things to the nth degree. If I wasn’t exhausted when I got home it meant that there was still something I should be doing or someone I should be spending time with. There must be some type of labor to be done, whether that was physical, emotional or otherwise.

This is what a woman is, I thought. This is what I should be doing, this is what I must be doing. This is what mom did.

I broke. I don’t know if it was just one moment or a series of moments, but I was the one sobbing while I thought others were sleeping, wiping tears in the glow of my laptop. Except there was no little kid listening on the other side of my bedroom door. It was just me.

I realized that if I keep working, if I keep giving this world and everyone around me everything I have, I won’t have anything left. It won’t be glorious for me, just as it wasn’t for my mom.

Working moms in this world aren’t just bringing home the bacon; they’re not ‘off the clock’ at 5 p.m. There is no overtime for the emotional labor that women, especially working mothers, put into the people around them, day in and day out.

Personally, I’m still working on remembering that. I can still feel that anxious tingle in the back of my head anytime I try to permit myself an hour to lay in bed, to not be obligated to something or someone. I have to remind myself that I don’t have to sign up for that extra project and that just because there is something out there to be taken care of it doesn’t mean I need to be the one to do it.

I don’t know if this is a call to action. I don’t know if this is a criticism of men or of the society who makes them or both. I can’t speak for anyone’s circumstances or experiences.

However, I do know that I’m not the only one who feels this way and that there’s an entire world out there of women, young and old, who right now, are giving more than they are capable of managing. To them, and to you, I just want to remind you that it’s okay to set boundaries. It’s more than okay — it’s normal, healthy and completely necessary to living your life in a way that’s sustainable.

Header image by Jenni Holtz

NO COMMENT