You could call it a problem. Or a crisis, or even a catastrophe — but not one of these words fully capture the gravity of the issue at hand. And how could they? When we’re able to name and categorize issues of this world, it’s because they have some defining characteristics. A specific time, place, politic, language.

Perhaps this is why there is no formal definition for “climate refugees.”

Formal definition or not, the climate refugee predicament is very much alive and growing at a rate that should demand the attention of those of us in the most secure social, economic and geographic positions.

On average, over 24 million people per year have been displaced by natural disasters since 2008, including over 1 million people that were displaced internally in the U.S in 2017 alone. This is a number that may only continue to rise if greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current patterns, which could lead to a 2.7 degrees Celsius rise in atmospheric temperature as early as 2040 — a threshold that, if crossed, could mean the complete destruction of coral reefs, the submergence of coastlines across the globe and a sharp increase in droughts, severe food shortages and floods, according to a report released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in October of 2018.

“What will happen first is more of what’s already happening,” said Dr. Christie Kilmas, a professor of Environmental Science and Studies at DePaul University. “Climate change will exacerbate problems in areas that are already not making quite enough food. It’s going to drop yields, change rainfall patterns by creating these strong storm surges, instead of the the slow steady rain that’s ideal for growing crops. And where food is scarce — which is not really in the U.S. — we’re gonna see those populations pushed out.”

Africa, largely speaking, is one area where crops have a low threshold for climate inconsistencies and as a result, the continent has already begun to experience surging levels of food insecurity.

“And when nobody has enough to eat, then that’s a factor of a lot of underlying conflict,” Kilmas said. “I want to be very clear that I’m not saying that climate change causes wars. It doesn’t. But it’s a contributing factor when the other factors are already there.”

As Kilmas noted, this whole process is only being exacerbated as the effects of climate change rise in severity and frequency with the continued emissions of greenhouse gasses.

Now it’s becoming more clear that these problems and the mass displacement that they produce are not an entire ocean away.

“We [in the United States] are more vulnerable than I had initially thought,” Kilmas said. “It’s likely that the hurricanes we see are more likely to be intense and to stall in areas, which is exactly what we saw in Houston [Hurricane Harvey].”

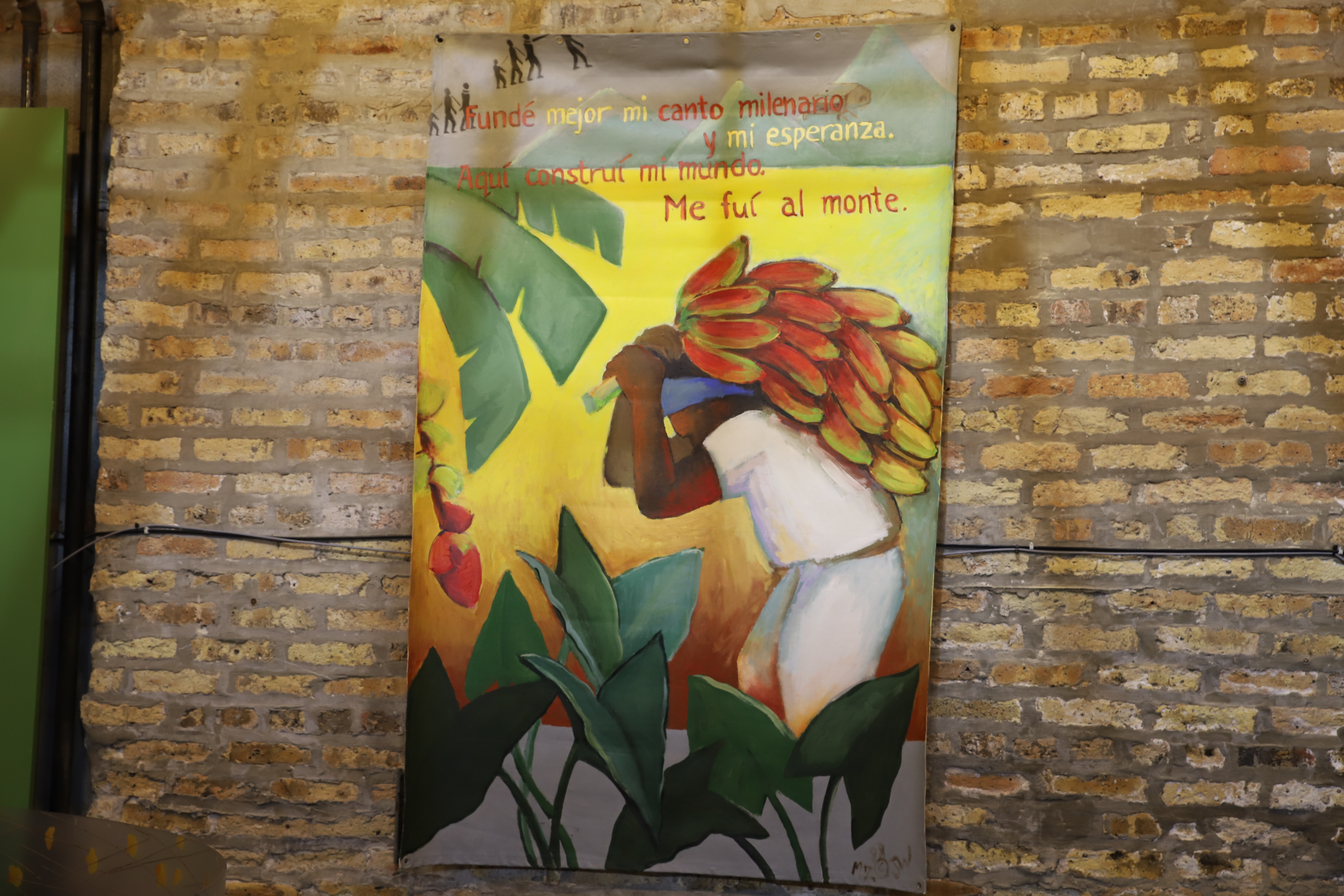

Segundo Ruiz-Belvis’s Executive Director Omar Torres-Cortright explaining the connection that the cultural center has to the surrounding Puerto Rican community through art, music and service. Photo: Francesca Mathewes, 14 East.

The social impacts

Social collapse as a result of climate change can come across as far-fetched. But, in an examination of recent climate disasters, it becomes clear that collapse of this scale is well within the scope of our reality.

Take for example the response to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico back in September 2017, which is now regarded as the fifth largest storm to ever hit the United States. The response to Hurricane Maria is now used as an example of governments being catastrophically underprepared for such disasters. It’s estimated that over 4,600 people perished in the storm and it took nearly a year for all of its residents to have restored power. Additionally there were clean water shortages, lack of medical resources and food that plagued the island for months following the storm.

Carlos Martinez experienced this firsthand.

“After Maria we didn’t have any water, we didn’t have any electricity, so we had to leave. It was really hard for us,” he said.

Martinez currently lives with his family in a suburb of Chicago and, like thousands of others, migrated here after the storm devastated his town of Gurabo, Puerto Rico.

“It was hard to leave my country, to leave everything behind,” Martinez said. He saw firsthand the chaos that compels people to flee their homes in the wake of climate disasters.

This kind of chaos can result in people sometimes making dangerous but necessary decisions in order to simply survive.

“We had to pay two gringos for some water. We don’t know where he got the water from, but we needed it and you do whatever you can,” Martinez said. “From the water I got sick and had to go to the hospital.”

Many Hurricane Maria refugees were received and supported by churches, nonprofits and community centers like the Segundo Ruiz-Belvis Cultural Center. It’s the oldest cultural center in the city, located in Chicago’s Hermosa neighborhood.

“Even though we’re primarily an arts and culture organization, when the hurricane hit Puerto Rico, as the longest standing Puerto Rican cultural center in the city [Chicago] we obviously activated in a very different way,” said Segundo Ruiz-Belvis’s Executive Director Omar Torres-Cortright. “The whole mission of the organization changed for that year after Hurricane Maria, and it continues to change because nothing will be the same after Hurricane Maria. We decided that during that year that we were gonna focus on providing as many services to not only people in Puerto Rico but to Puerto Ricans that have been displaced and find them homes in Chicago.”

Given Chicago’s large, diverse population, designation as a “sanctuary city” and its distance from the coasts and areas more susceptible to the effects of climate change, increased migration into the city isn’t out of the question.

“As far as climate migrants are concerned, as is true with most refugees, they travel as physically close to their homes as they can. When you’re talking about refugee situations it’s not as if someone has planned an air ticket out of the problem,” said Rajit Mazumder, who currently serves as the chair of DePaul’s graduate program in Forced Migration and Refugees Studies. “So in that sense, people coming to Chicago will only be coming to Chicago because of preconceived plans or because another authority, a state or NGO type of authority has created the means by which they can travel.”

The role of the state and NGOs (non-governmental organizations) in the relocation of displaced peoples also draws city governments into question. Given the current projected impacts of climate change, how can Chicago prepare itself for a potential influx of displaced people?

According to Mazumder, successful resettling policies at the city level must be completely comprehensive.

“It has to go through all sectors of society and government,” he said. “Where will people get employment? How long will they be supported? Will they be sent back? If it’s an environmental problem like flooding, what will happen when the flood waters recede?”

The response

Community organizations like Segundo Belvis-Ruiz could also play a crucial role in the acceptance and placement of climate change refugees, given the current climate trajectory sustains itself.

“It was a process that we put together with the city of Chicago and the Office of Emergency Management to try to find private and public resources to help Puerto Ricans. We knew the city alone was not going to be able to do that work that was needed to be done to receive upwards of 4,000 Puerto Ricans that had to come to Chicago,” Torres-Cortright said. “But I’m more concerned with the federal response than the local response. At the federal level we see gross negligence that cost us lives. That’s really what happened.”

He’s not wrong. The Federal Emergency Management Facility released an internal report acknowledging the agencies inadequate preparation and response to Hurricane Maria, including understaffing, massive communication and logistical errors and the misallocation and/or lack of proper funding.

The city of Chicago’s Office of Emergency Management did not respond to multiple requests for an interview in time for the publication of this article.

Another important thing to consider when discussing resettlement policies is the response of existing populations to incoming migrants. Will they be welcomed? What social circumstances would an influx of migrants create down the line?

A look forward

“It’s one thing for the government to lift people — for example, let’s say the government lifts people from Chicago and brought them here. And then the Chicagoans don’t want them. What if they’re a different race, or a different religion, that creates all kinds of problems,” Mazumder said. He cited Minnesota as an example of a model resettlement policy. During an era of crisis in Somalia, Minnesota became a relocation site for thousands of Somali refugees and their families, including Sen. Ilhan Omar.

“And that’s the best thing this country can do, is allow those kinds of things to happen,” he continued. “To have a successful settlement policy it has to be an acceptance by the people in this community where it’s going to be established, as well as by federal and state authorities that make the infrastructure possible for this to happen. Because you know you’re going to need school, hospital, roads, etc.”

However, Mazumder also had his doubts and concerns about the city’s ability to successfully integrate and support an influx of climate change refugees, given the lack of resources and funding for its existing communities.

“In Chicago, we can’t even look after people on the South Side. So the reason Puerto Ricans often came here [after Hurricane Maria] was because they had personal family structures, not because the city of Chicago is necessarily a great place to come,” Mazumder said. “And I think this is true for all cases, as I don’t think most United States cities are doing a great job with their own current populations. So to deal with this problem — especially in a sudden influx of 1,000, 2,000, 3,000 people — it’s going to fold in on them. Look at the city of Chicago right now — financially and everything else. Where will the city fund these people?”

Additionally, increasing awareness about climate change refugees — specifically focusing on communities that are disproportionately affected — can help grow the conversation amongst communities and policy-makers alike.

“I think the coverage and the assistance should’ve focused on the people that really need it, even now,” Martinez said. “Me and my family don’t need it. But people over there in the mountains — and Puerto Rico isn’t flat, you know — they don’t really help those people who really need the help.”

Above all, best practices for conversations and policies surrounding climate change refugees will involve confronting deeply rooted attitudes about immigration that exist in current discourse.

“It’s basic human condition that we don’t like outsiders. From the point of the migrant it’s that you need. Your absolute basic existence: life, food, water, security, sanitation, health…forget about education, employment all of those things. Whether you survive or not is at risk,” Mazumder said.

“So the last thing that you want is people saying they don’t want you, because you have nowhere else to go. And on the other side you have basic human psychology where we don’t like outsiders, we certainly don’t like foreigners or people who don’t look or speak or dress like us,” he continued. “This is the same psychology that’s created the argument about ‘illegal aliens,’ that they’re taking something from us. If you tell someone ‘Oh, they may be illegal but they’re coming here because there’s no longer sustainable farmland in Guatemala,’ they’re not going to listen to that. It’s something in us that has to shift.”

Header photo by Francesca Mathewes, 14 East

NO COMMENT