***Warning: This article contains spoilers for the film Us***

Jordan Peele’s Us might just be the best film of the year so far and also the most ambitious, original and thought-provoking horror film in the last decade.

In Peele’s 2017 film, Get Out, audiences were mesmerized by the portrayal of liberal racism in America when a Black man visited his white girlfriend’s family.

In his latest film, Us, Peele brilliantly examines the social class system by exploring the oppressed, the outsider and America’s current divided political state by making complicated and clever social allegory.

Plot Refreshment

Us follows the Wilson family, headed by the matriarch, Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o), the goofy dad, Gabe (Winston Duke), and their two children — the mask-wearing Jason (Evan Alex) and the cross-country-running Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph).

The Wilsons are on their way to Santa Cruz for a relaxing beach vacation only to find out that it’s the same beach where Adelaide had a traumatizing childhood encounter with her menacing doppelgänger, Red. Red has been living underground with other doppelgängers, which are clones she refers to as “the tethered.” Red explains to the Wilsons that the doppelgängers are called this because they share a soul with their human counterparts.

At the end, we see the Wilsons driving off in an ambulance, thinking they are safe, until we see in a flashback revealing that Red knocked out the real Adelaide, locked her underground and took her place. The film then ends with a long shot of the tethered holding hands across America.

Nature versus Nurture

One of the film’s biggest shocks come when we find out that we’ve been following the tethered version of Adelaide all along. Because of the twist, the viewer now has an entirely different way of looking at the characters and their motivations. Who should we be rooting for now? Who is the true hero and who is the true villain? Peele’s decision to include the twist at the end flips everything upside down.

Young Adelaide (Madison Curry) seeing her doppelgänger for the first time before being locked underground for decades. Universal Pictures.

We don’t know much about young Adelaide’s past, but we do know when human Adelaide gets trapped underground with the tethered, she adapts to her environment by using what she remembers from above ground to teach and liberate them.

She simplified the corny Hands Across America message in order to unite the tethered, give them a purpose and exact her revenge. She informed the tethered by using specific memories from her childhood, i.e the Michael Jackson “Thriller” t-shirt she won from the boardwalk. She also gives herself the name Red, possibly after the memory of the red candy apple that she held while wandering the boardwalk as a child. She uses those positive memories and resources from her above ground human life to now basically live as a sub-human for decades with the tethered underground.

On the other side, we have the sub-human version of Adelaide, aka the clone, who now has switched places to live freely above ground — the only one to do this. Her parents are clearly unaware of the switch but take her to therapy because she hasn’t spoken since she got lost at the boardwalk.

After years of being able to express herself through dance, the clone version of Adelaide is able to thrive, have a normal life and eventually learn to speak. She is essentially living the American dream — married with two kids, able to afford a nice vacation, socializes with “friends” and is part of the American middle class. An interesting concept that comes up because of this is the debate of nature versus nurture. However, we never really know if her development was the result of innate nature or a nurturing environment.

The Oppressed/Class System

Class inequality is also a major theme throughout the film. When Red is explaining the origins of the tethered to Adelaide in the chilling finale, she says the government (who might be the true villain here) was able to copy the body, but the not soul. Red says without the soul there’s no free will.

The government created copies of everyone and wanted to use the tethered as a way of controlling the humans above. When the government realized the copies would just mimic the actions of their above-ground version, they abandoned them underground and the experiment all together.

Red (Lupita Nyong’o) in one of the underground classrooms explaining the origins of the tethered. Universal Pictures.

The tethered were left down there mindless, thoughtless and without purpose. They were trapped, ignored, forgotten and oppressed. They were only able to “untether” (create free will) from their above ground versions when they realized that human Adelaide, who was also trapped down there with them, was different. For them, she was a prophet who had a voice and provided them purpose. It took one individual to liberate an entire group.

Earlier in the film, when Red is telling the story of the girl’s shadow by the fireplace, she explains that when the above ground humans got warm food and soft toys, the tethered down below got the opposite. After the story, Gabe confusingly asks Red, “Who are you people?” to which Red creepily replies, “We’re Americans.” It’s a story and a reflection of the blockade between socioeconomic classes in America and how marginalized groups are pushed out of sight or forgotten about.

Jeremiah 11:11 becomes a recurring symbolic number and theme throughout the film, from the homeless man in the beginning, to the number 1111 being on top of the ambulance at the end. The time 11:11 is shown on the clock in multiple scenes, which is a mirror reflection of its own, and when Gabe is watching a baseball game the score is 11-11. Jeremiah 11:11 translated from the King James Bible reads,

“Therefore, thus saith the LORD, Behold, I will bring evil upon them, which they shall not be able to escape; and though they shall cry unto me, I will not hearken unto them.”

Pretty straightforward, but also extremely dark and depressing, which fits the second half of Us. One interpretation is that the “LORD…will bring evil,” aka the tethered, as punishment because we forgot about them, abandoned them and oppressed them.

The Wilson family walking along the Santa Cruz beach. Their shadows resemble 11:11. Universal Pictures.

Reliance on Technology, Possessions and Social Image

Peele drops subtle hints throughout the film that sometimes we rely too much on technology and material possessions. In the film, the Tylers (the white family) and the Wilsons are always trying to maintain a perfect image by having the “nicer” things in life and the right technology.

Gabe feels particularly inferior to Josh (Tim Heidecker) because of his possessions and social status. The Tylers represent the white upper-class family in America by having the shiny objects like the bigger boat with the flare gun, the nice house with the backup generators and the luxurious SUV that Zora gets to drive later in the film.

Even though the Tylers look good on Instagram with all their possessions, in reality, their life is unhappy and Kitty (Elisabeth Moss) jokes about how she wants to murder her husband Josh. There’s a recurring joke throughout the film that the white dad is trying to one up the Black dad. It’s a light joke throughout the beginning that provides a deeper meaning later about class and social status.

For the Tylers, however, their technology failed them. Ironically, when Kitty tried to use her Alexa equivalent, Ophelia, (which derives from the Greek word “opheleia” meaning “assistance” or “help”) to call the police, it misinterpreted her words and played “F—k tha Police” by N.W.A. instead, resulting in her death.

Hands Across America

When the film opens, a young Adelaide is watching a corny commercial on TV for Hands Across America. She is also wearing a Hands Across America t-shirt before her dad wins her the “Thriller” t-shirt at the boardwalk, which also happens to be prize number eleven.

Hands Across America was a public event on May 25, 1986, in which 6.5 million people held hands for fifteen minutes to form a continuous human chain across America. The proceeds were donated to local charities to fight hunger and homelessness and help those in poverty.

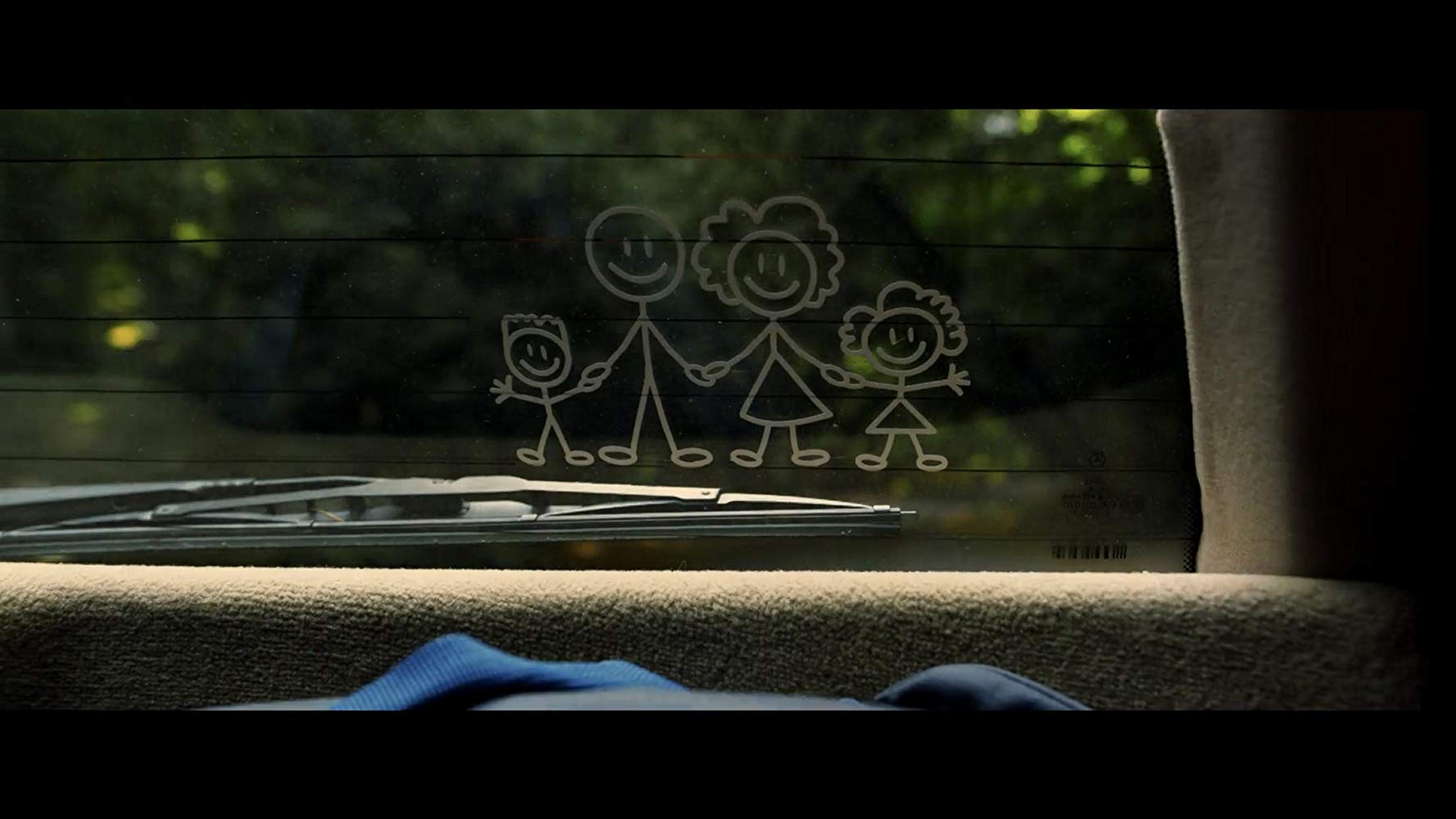

- The Wilsons family sticker decal on their car foreshadowing the Hands Across America theme. Universal Pictures.

- The tethered versions of the Wilsons lined up on their driveway in the same order as the decal.

The event raised $34 million, but only about $15 million was distributed to local charities after deducting operating costs, according to The New York Times. Michael Jackson was also heavily associated with Hands Across America as a promoter of the event and co-writer of its theme song. The final moments of the film reveal that the tethered have spent decades planning to resurface and hold hands in a violent restaging (Gabe thinks it’s performance art) of Hands Across America inspired by the commercial.

“Hands Across America was this idea of American optimism and hope, and Ronald Reagan-style-we-can-get-things-done-if-we-just-hold-hands,” said Peele to Vanity Fair in an interview. “I wanted to say something about the state of this country. It’s the one I live in. It’s the one I know best, and it’s the one that I have the most complicated pride and simultaneous guilt about being from.”

Fear of the Other/Outsider

Peele also said the film is fundamentally about America’s misplaced fear of outsiders. “This movie is about this country,” said Peele in an interview at South by Southwest. “We’re in a time where we fear the other, whether it’s the mysterious invader that we think is going to come and kill us and take our jobs, or the faction we don’t live near, who voted a different way than us.”

“We’re all about pointing the finger. And I wanted to suggest that maybe the monster we really need to look at has our face. Maybe the evil, it’s us,” said Peele. What Peele is saying is that it could be us as the personal pronoun, or it could be us as in the U.S. aka the United States.

Throughout the film, the above-ground citizens of Santa Cruz and the U.S., including the Wilson family, automatically react in fear when they see the “other” or the tethered. Even though the tethered look exactly like us, they don’t act like us or communicate like us, so we immediately think they are the enemy. The fact that they are wielding scissors doesn’t help, but the point is that we don’t know where they came from and we don’t understand their motivation.

Their purpose was simple in the sense that their entire goal was to kill their above ground versions, be free and then join hands with their fellow tethered in a Hands Across America demonstration. If it wasn’t for Red liberating them, we wouldn’t even know of their existence.

The Wilsons doppelgängers, (from left to right) Abraham, Umbrae, Pluto and Red, after they broke into the real Wilsons vacation home and confront them.

Conclusion

In the end, Peele cleverly and ambitiously threads multiple social commentaries into a singular plot, and while some questions or theories remain unsolved, the fact that we are even thinking about it speaks volumes. Peele wants us to reflect on who we really are as a society, a nation and an individual by challenging our way of thinking.

Us says a lot about us and whether we realize it or not, especially in America, one appearingly progressive event might come at the expense of someone else’s suffering. At the end of the film, Red asks Adelaide why couldn’t they share the freedom together, but in our society, it seems as if one person’s freedom means another person’s imprisonment.

NO COMMENT