Incarceration means limited access to a lot of things: loved ones, freedom and the outside world. However, something we don’t often think about is reading. Even with access to prison libraries, incarcerated people are still underserved when it comes to available books, and the prison system makes it difficult for outside organizations to get books into their hands.

There are over 25 books to prisoners programs around the nation that work to change this.

I spoke with Barbara Kessel, who works with two programs in Illinois: Reading Reduces Recidivism, known as the 3Rs project, and Urbana Champaign Books to Prisoners. Although both organizations work to get books to prison libraries, their goals and the ways they accomplish them are different.

UC Books to Prisoners

Urbana Champaign Books to Prisoners began before 3Rs in 2004, after the state cut back on funding for prison libraries. They are focused on involving the community and educating members of the community about prisons.

The biggest difference between 3Rs and UC Books to Prisoners is the way in which they get books to the inmates. 3Rs has the prison librarians come pick them up while UC Books to Prisoners mails them out. Their program gets letters from inmates and mails them books based on the information in the letters.

“A key staff of volunteers, a dozen or so, come in on Tuesday or Thursday afternoons to read letters, make packages with the books, say what’s in the packet, rubber band it, and send it next door where they do the bulk mailing,” described Kessel.

This program is unique in that they track every book that they send out. They have a database filled with all the information.

“They know who’s gotten something already and they are organized so that volunteers know which requests are first time requests and which are repeat requests so it’s easier to prioritize.” said Kessel.

The community can get involved with the program in different ways. There are donation bins across town and around the University of Illinois’ Urbana-Champaign campus. Many of the volunteer groups that come in to help package books are student organizations from the university.

“We want to educate the community by having as many volunteer groups come in as possible,” said Kessel. “We have volunteers read and answer letters and encourage them to leave a note with the book.”

This process can aid with trying to break down the prison guard mentality, the idea that people who are incarcerated don’t need to read or educate themselves because they’re in for life. This can be broken down by educating communities. Book programs across the nation work to reinforce that books and education are not only a fundamental right, but that they have the power to reduce recidivism.

A study done by the RAND Corporation, a global policy nonprofit, found that incarcerated people who participate in prison education programs have 43 percent lower odds of returning to prison than those who do not.

A similar study done by the Department of Education, the Three-State Recidivism Study, found that those who participate in education programs are 29 percent less likely to return to prison within three years than those who do not.

3Rs Project

“3Rs doesn’t mail books,” said Kessel. “Prison librarians come with vans to pick up the books that we get donated to us.”

3Rs began in 2010 and started, similarly to UC Books to Prisoners, because of the lack of state funding for prison libraries. Kessel met with other librarians in the Champaign County area to start 3Rs. Kessel described how they were under the impression that the libraries were getting some books, but wanted to find out the extent of it.

“We decided our first step was to call and talk to librarians at each of the prisons in Illinois,” said Kessel.

Kessel and two people on her team split up the list of 26 correctional centers and began their research. Over the course of three months, they came to find that one-third of the prisons no longer had libraries because they didn’t have a librarian, one-third had a somewhat functioning library with a librarian present and the final third didn’t have a librarian but guards were allowed to take cell blocks, a unit made up of multiple jail cells, into the library.

After several months of research, they got into contact with a prison that was interested.

“I spoke with a young woman who was in her first year working at Taylorville Correctional Center,” said Kessel. “She was hesitant to work with us at first because of the lack of space but we eventually worked out a sort of book trade deal. Unfortunately, her boss wasn’t comfortable with the situation as the woman was only in her first year, so we were never able to get into Taylorville.”

The first prison they got into later in the year was Dwight Correctional Center, located in Dwight, Illinois, an hour southwest of Chicago. Kessel and her team got into contact with Beatrice Stanley, Dwight’s librarian, and set up a system where volunteers collected books and drove them to Stanley.

“Beatrice always said, ‘Wardens come, and wardens go, I censor the books, bring them to me,’” said Kessel. “That was not the situation in other libraries.”

After Dwight, an all women’s facility, was closed in 2013, all the women were moved to Logan Correctional Center in Lincoln, Illinois, roughly 3 hours southwest of Chicago.

“Logan has the smallest library and the warden there does not want a single book,” stated Kessel. “The women there have not been very well served. They don’t have a good library.”

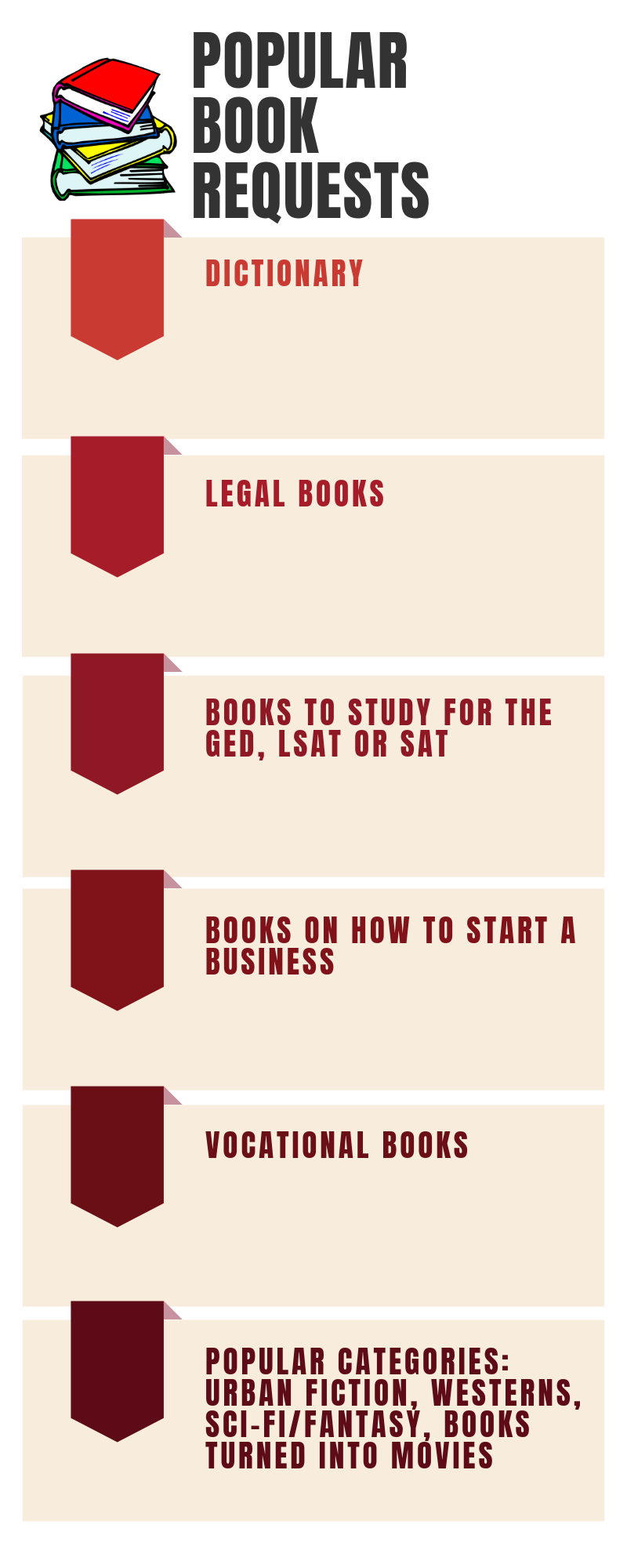

Infographic by Abby Yimmer, 14 East.

Challenges That Come Along the Way

There are currently four active 3Rs chapters serving the entire state except for Chicago. It’s been difficult for 3Rs to get into maximum-security prisons, so there is no chapter in the city.

“We don’t want to set up a chapter if there aren’t ways for us to serve the people,” said Kessel.

She continued to describe the difficulty of serving prisoners in the Chicago area because Stateville Correctional Center and Pontiac Correctional Center both don’t allow books.

“Stateville is an enigma,” said Kessel. “They had an educational facilities administrator who I spoke to about bringing books or having people come to get books and she said, ‘We don’t need any books because most of our prisoners are lifers, so they don’t need to read.’ That is the perfect representation of prison guard mentality which sadly some people have.”

14 East reached out to Stateville regarding their policies, though the prison did not respond before publication.

This prison mentality, and the many rules and regulations that are in place, make it difficult for organizations to accomplish their goals. Stephanie Norick, who worked at 3Rs, has had some firsthand experience.

“I used to work with the central western Illinois correctional centers,” she said. “There’s just a lot of rules, and the rules aren’t really clear.”

Norick wished that there was better communication of the regulations so that organizations could be better prepared.

“The regulations weren’t always communicated to us so it’s hard to follow the rules,” Norick said. “We usually don’t find out until later.”

UC Books to Prisoners also has had difficulty trying to understand specific rules and regulations.

“Each prison has its own finicky thing about packing for example,” said Kessel. “There is a censor list of things you can’t send but it changes all the time and they won’t let you see it. In the past, they haven’t allowed LGBTQ+ material but they are starting to soften on that.”

To dive into restrictions on LGBTQ+ material I spoke with Melissa Charenko who works at another organization focused on getting books to incarcerated LGBTQ+ people called LGBT Books to Prisoners.

“The biggest challenges we encounter are prison restrictions,” she said. “It is particularly frustrating when they have bans on books such as Trans Bodies, Trans Selves. This book is an amazing resource guide for transgender people, it contains medical diagrams and information on safer sex. It’s really disheartening when LGBTQ+ books are singled out for bans.”

This project grew out of the organization Wisconsin Books to Prisoners. One of the volunteers, Dennis Bergren, noticed that there was a need for books that offered education and empowerment to some of the most marginalized in the prison system.

Charenko hopes that through this program, people will understand how the prison industrial complex affects marginalized communities like LGBTQ+ people and people of color.

“We get letter after letter which explains the violence of the system as it polices sexuality and gender, separates loved ones, and especially targets low-income, gender variant, people of color,” said Charenko.

Why Does It Matter?

The mission of UC Books to Prisoners, in addition to providing books, is “to educate ourselves and our community about prisons.”

Simon Carless who works with Prisoners Literature Project described how prison book programs are currently under attack by states who are trying to ban them.

“Looking at the recent news you can see individual banned books in various states as well as some states trying to ban used books from all organizations,” said Carless.

Providing books to people who are incarcerated, along with prison education, can bring change.

Carless noted the reasons that are outlined on their website for why they send books and the importance of having book programs across the country. The importance of inmates having access to books.

“Activists and artists have written about the great solace they received from books in prison,” he pointed out on their website. “Every month we receive thank you letters from prisoners echoing the same sentiment. The American prison industrial complex is frighteningly huge but with your help, we can continue to make a positive difference for thousands of people each year.”

Header illustration by Jenni Holtz.

NO COMMENT