The increased implementation of technology in the classroom, such as computers, internet research databases and online learning programs, has created two central parties of thought in public discourse.

The first is the argument that all technology is good. Computers and the internet in the classroom only add to the enrichment of the students who utilize them. Radicals on this side go as far as to argue that the physical school might fall obsolete as the children and adults of tomorrow surf the web for diplomas (cue the “Education Connection” jingle).

The second party’s stance reads like a cringey meme-worthy “Boomer” comic. In an illustrative form of this realm of thought, a wizened teacher leers over a bright-eyed child holding a dictionary and chastises: “There’s no search bar in that, kid.” Technology to them is seen as the degenerative bane of primary education in America, compared to the ruler-slapping analog days of yore.

(Justin Myers, 14 East)

The upside of classroom technology

Over the past decade, technology in the classroom has exploded with the maturation of the internet. The rapid innovations that have followed have only added fuel to the fire of the technological debate, pitting the two sides against each other even more.

At Medgar Evers Elementary School in Chicago’s South Side community area Washington Heights, this has been especially prevalent. Though commonplace in its classrooms today, the appearance and implementation of technology in its classrooms was a slow process.

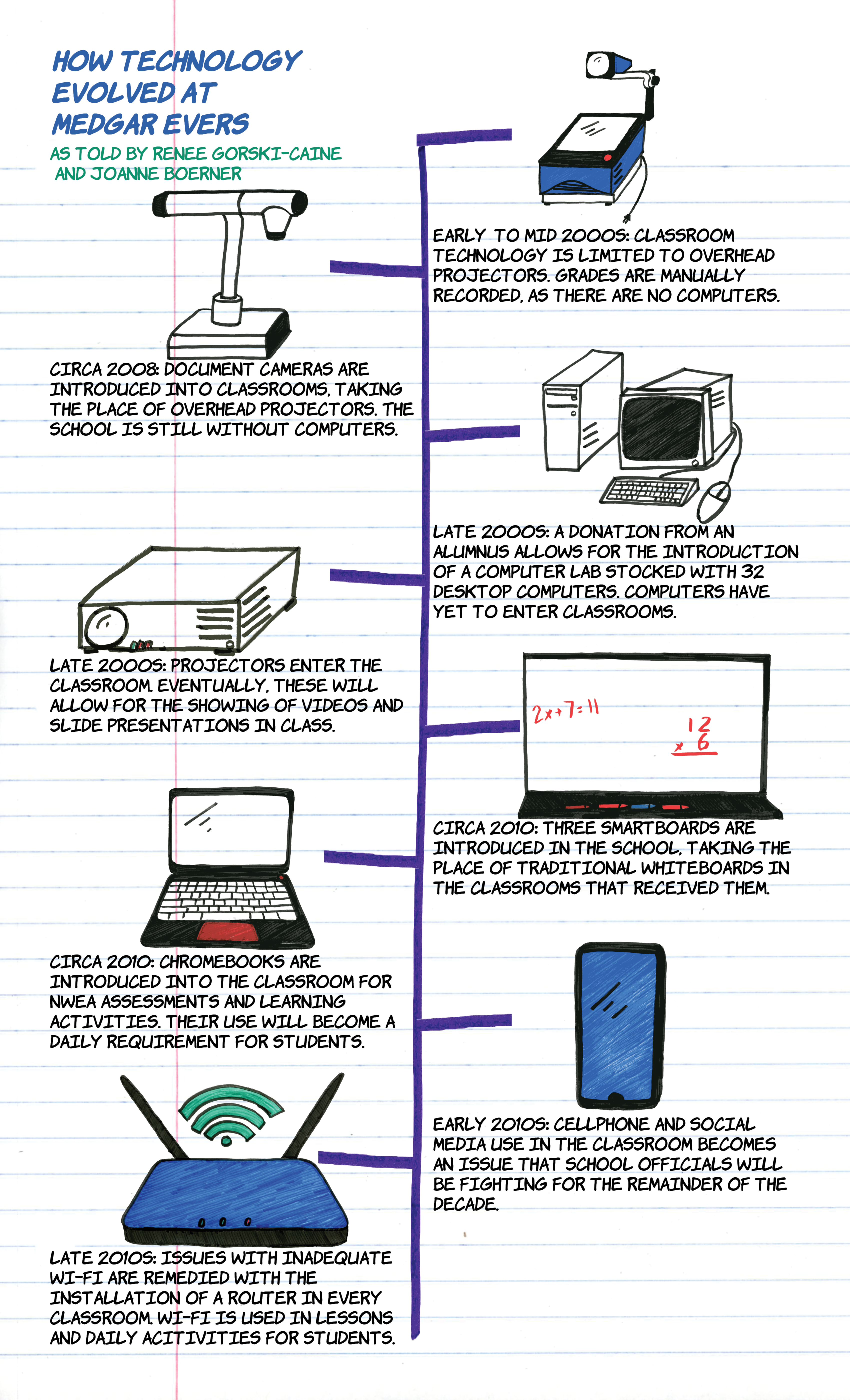

“They weren’t cutting edge in getting anything soon,” said Joanne Boerner, a second-grade teacher at Medgar Evers with 24 years of teaching experience. “There really wasn’t anything in the classroom until maybe about 10 years ago that we started even introducing computers.”

Medgar Evers’ status as a South Side school within Chicago Public Schools (CPS) was a further roadblock in acquiring technology, noted Renee Gorski-Caine, a sixth and eighth grade special education teacher at Medgar Evers with 16 years of experience.

“South Side [in the CPS system] is behind what you would see on the North Side as far as technology,” she said.

Neither divulged specifics as to why funding was not being invested in technology within South Side schools, though CPS is no stranger to talks about resource inequities among its various schools, especially when it comes to those on the South and West Side.

Most recently, these issues as they related to school staffing were manifested in the 2019 Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) strike. Back in 2012, a similar strike took place. However, unlike the 2019 one, the 2012 strike focused more on the perceived over prioritization of schools’ performances above all else. This, in addition to the lingering effects of the 2008 recession and educational reform policies introduced by the Obama administration, meant that schools were primarily focusing their attention on the bare essentials, such as avoiding staff cuts.

It was only through a donation from an alumnus that Medgar Evers received its first computers towards the end of the 2000s, a set of desktops contained in a lab.

Boerner explains that she noticed disparities between Medgar Evers and the private school her children attended because of the school’s slow progress of technology acquisition.

“[My children] had technology, and they were researching and doing things that we didn’t even have in the public school system,” Boerner said. “They were using [technology] every day, and they were using it on their homework. Within the private schools that my own children went to, I saw how much they used it and how helpful it was. Because of that, that in turn made our household get computers and become acclimated to the computers.”

In an internet age, she believes these computer skills are necessary components of life.

“The world and everyone around us is just moving at lightning speed with technology,” Boerner said. “I think we definitely need to keep them abreast of things and how to use these things. But, we still have to give [students] the basic foundation of learning and inquiry, so they don’t depend on the computers because we still have issues with technology [not working].”

Despite a slow start at its beginning, at the end of the decade, students at Medgar Evers use computers and online programs each day as required in in-class work. Nowadays, while disparities still exist such as a cited lack of smart technology such as iPads, there is a consensus among interviewees that the district has become more apt to innovations in technology at the decade’s end.

“Our students use [the learning program] Compass, and they’re required to do three reading and three math activities during the week,” said Gorski-Caine.

“[The Chromebooks] also went along with the standardized tests that were being implemented into the school systems,” Boerner said. “They then allowed us to have these Chromebooks so that the kids could use a study program for the standardized test.”

In time, their use expanded to include the aforementioned Compass program, which tests students to give them tailored lessons that respond to their individual needs in specific areas of study. This is accomplished through a series of online lessons and learning materials.

“I really believe that it enhances the learning,” Boerner said. “For one teacher, it is very difficult to try and reach every level. I think by doing this and having this available, it gives those kids that much of a different chance to work at their level.”

However, there are some points of disagreement.

“I would not say that [these programs] enhance instruction all the time,” Gorski-Caine said. “It does enhance instruction for kids that do want to learn. But, for those kids that education is not important or they’re struggling, it does not help them.”

She points towards the ability of students to bypass the school’s web blocks to access YouTube videos, games and music during their study time on the programs and lower-quality graphics within the programs themselves as the causes for this issue.

“The graphics are not even remotely close to the graphics on their video games — they’re childlike graphics,” Gorski-Caine said. “The students don’t respond to that, especially in middle school. They’re used to much more sophisticated graphics. For a child with ADD or ADHD, or even ODD, which is oppositional defiant disorder, the computers are just a way for them to get around the blocks and play shooting games.”

She said that this tendency requires the teacher to be constantly vigilant with what their students are doing in the classroom. However, when a student needs individual help on their computer, this isn’t always possible.

“The problem with computers is, if you are sitting there helping one student at a computer program and it’s a multi-step problem and it takes time, then that teacher’s tied up with just that one student,” Gorski-Caine said. “You could spend 20 minutes working with just one student. Then, in that case, if the other kids are stuck, they’re just sitting there. And, they’re talking, and they’re off task. They’re not engaged, and they’re not learning.”

In addition to ensuring that students remain on track while helping those who need it, the teacher is additionally challenged with making sure students use the programs properly.

“Some of them just run to the questions [in the program] and don’t even do the tutorial,” Boerner said. “You have to teach them that this is your teacher for the next 30 minutes, and the screen is going to teach you, whether it’s phonics, a passage or adding or a story problem.”

Boerner explained that, though the programs are online, the teacher still plays a physical role in the classroom.

“You’ve got to always evaluate and go back and see what they’re doing on the computer and make the corrections if needed,” she said. “We can’t just let it go. So, it’s just become a different type of avenue for learning, but the teacher has to absolutely pay attention to what is going on.”

Gorski-Caine believes that it is through the expansion of this hybrid approach combining the physical presence of a teacher with the online program that many of her previously mentioned issues may be remedied.

“I would like a program where I’m teaching, and it’s putting me and my whiteboard on their computer,” Gorski-Caine said. “I would want it to be interactive where I could draw a problem on my board, and it would show up on their screen. And, they could put the answer in or work the answer out, and it would send it to me, or I would see a pop up on my screen.”

In the technologically evolved classroom of 2019, Gorski-Caine’s call for further hybridization isn’t the only place where a search for a multimedia approach to education can be found.

“I’ll maybe play a short three-minute video to introduce a concept from a reading lesson, for instance, or I’ll use a YouTube video to demonstrate a math skill once we get started with it,” said Chad Heeren, a seventh-grade special education teacher at Medgar Evers with 12 years of experience.

In addition to video, he said that he also makes use of PowerPoint and Prezi to create engaging lesson presentations for his students. He points towards the online programs as additional supplements to aid in learning.

Though commonplace in the classroom today, projectors in the classroom allowing for the showing of online movies and computer-generated presentations were not found in the classrooms at Medgar Evers until the 2010s. These worked in conjunction with the then newly introduced computers. Prior to the introduction of projectors and classroom computers, teachers were limited to overhead projectors and transparencies for much of the 2000s until document cameras were introduced at the end of that decade.

“2011, we got projectors — some of us, so we could hook a projector up to a computer and show like a Khan Academy video,” Gorski-Caine said. “Like, [videos on] how to work, how to do problems. And, science, like showing videos of nature and things like that.”

She said that teachers also received access to programs like Khan Academy that provided a library of instructional resources to supplement students’ learning. The provision of computers for teachers around this same time allowed teachers to get connected in the classroom for the first time.

(Justin Myers, 14 East)

However, this new frontier was not without its challenges.

“We had a lot of problems in the beginning with the children having to wait in front of a screen for it to come on, or if it was on, it would knock them off,” Boerner said. “That was very difficult to deal with because kids’ attention spans are very short if the computer wasn’t working properly in the first place.”

Boerner traces these issues to system problems arising from an inadequate network infrastructure in the building. She said in recent years this has been remedied through improvements in the school, such as the inclusion of a Wi-Fi router in every classroom in the second half of the decade.

The downside of classroom technology

An additional development of technology that has taken place over the course of the past decade in the classroom is that of student-owned cellphones — a concept that was foreign at Medgar Evers throughout the 2000s. Their appearance towards the start of the 2010s presented a unique set of problems for school administrators.

Gorski-Caine explained that a series of incidents at the start of the decade, mostly involving children at school using the devices for lewd photos of themselves and others, led to an administrative crack-down.

“At first, the kids had to turn their cellphones into the teacher, and the teacher would lock them up in a locker,” said Gorski-Caine.

Though, this methodology wasn’t perfect. Failure of teachers to properly secure the devices and cases of teachers tasking students with the responsibility of handing the devices back to their peers led to cases of theft.

Nowadays, Boerner explained, students are not allowed to bring them in without their parents filling out a signed form. In which case, the cellphone is still collected, albeit with stricter security measures, and returned to them at the end of the day.

“It was a giant distraction until the school put in the rules about having cellphones and collecting them,” Boerner said.

However, this hasn’t kept the issue of home devices out of the classroom. The rise of social media became a pervasive epidemic in the classroom during the 2010s, noted Gorski-Caine.

“It’s the social media aspect that is a daily battle with kids,” she said.

She blames the easy dissemination of information and, more noticeably, misinformation over social media for the magnitude of the issue.

“They get into fights, they talk about each other,” Gorski-Caine said. “They think things, they post things about each other, and it all comes back.”

Though issues with drama and bullying have always plagued elementary school lives, she said that social media has caused the issue to explode.

“Before, you might have had one or two students that cause drama in the classroom,” she said. “Now, everybody who’s got a cellphone is involved. Everybody who’s got a cellphone heard about it. It’s very difficult. We didn’t have the drama. We didn’t have the problems that we have now.”

Heeren said that the issue has not escaped the watchful eye of the school’s administration.

“From what I’ve heard and from what I’ve experienced and seen, [the administration] does a good job of talking one on one with some of the parties involved and talking to them about this is a wise way to use social media and this is a negative way to use social media and making sure the students know what’s appropriate and what’s not,” he said.

In additional to emotional wellbeing, these issues have impaired the students’ social health.

“They don’t know how to talk to one another,” Gorski-Caine said. “They don’t know how to have a conversation. They don’t know how to socially accept people who are different and not part of their friends in their Snapchat.”

Boerner noted a similar social impact.

“I think the way people are using the computers and cellphones, it really limits some of the interaction between the kids,” she said. “We’ve got to make sure that the children that we’re teaching are using the technology in a manner to whatever they’re learning to speak to the other children or to work together toward an end.”

Thus, the two schools of thought presented at the start of this article retain their individual merits in their own rights. While ushering in new learning opportunities and allowing for tailored educational attention to each student, the past decade’s worth of technology introduced at Medgar Evers Elementary School has also brought with it challenges affecting both students and teachers.

Though a complete resolution will take time to achieve to ensure that those challenges are overcome, Boerner lends her voice to express what she believes is the key to finding one:

“You have to be very, very vigilant about what [students are] doing and how they’re doing it and using it in the proper way to enhance their learning and not in place of their learning.”

Header image by Justin Myers, 14 East

NO COMMENT