Sanders won in Humboldt Park, and Warren won in Hyde Park

Monday was Anneke Thorne’s second time caucusing. In 2016, she caucused back home in Iowa with her friends, family and neighbors. This time, most of the people Thorne caucused with were unfamiliar to her. That’s because the Iowa resident is a senior at University of Chicago. Instead of going home to caucus, she participated in a satellite caucus at University Church in Hyde Park.

“It feels way more high stakes than four years ago,” Thorne said. “I was 17 years old four years ago, I was able to caucus because I was going to be 18 by the election and it was all so new and I had so much hope for the future. I had so much, like, hope that my candidates were going to do well.”

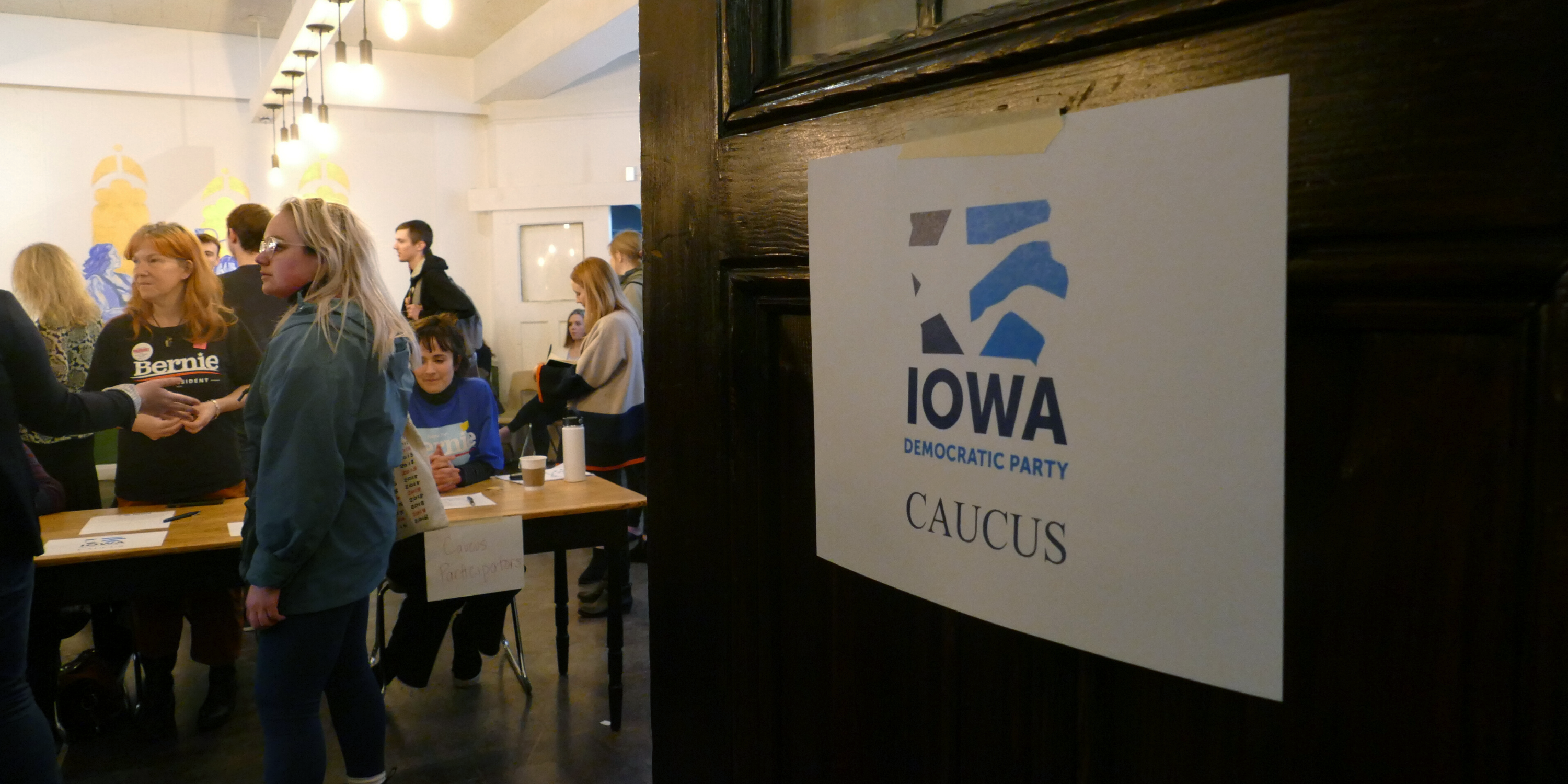

On Monday, about 170,000 Iowans participated in the 2020 Iowa Democratic caucuses. For the first time since the Iowa caucuses began to open the primary cycle in 1972, more than 90 satellite caucuses took place both within the state at non-traditional locations like nursing homes and college campuses, and around the world, from Paris and Glasgow, Scotland, to Brooklyn and Tucson, Arizona. Some were also held at different times in Iowa to accommodate Iowans with varying work schedules. This came in an effort to make the process more accessible to Iowans after growing concerns of the barriers to entry.

The satellites didn’t directly address issues of fatigue, pain and sensory overload that can arise for some caucus-goers. The event is often crowded, hot and in loud rooms of people standing for an extended period of time, making it more difficult for seniors, people with disabilities and sensory sensitivity, and parents with children to participate in the process. However, the satellite caucuses did make it possible for some Iowans unable to get to their precinct to participate — whether abroad for military duty, in another state for college or living in a nursing home.

Chicago hosted two satellite caucuses, one in Hyde Park and the other in Humboldt Park. In total, 44 Iowans — mostly young people — caucused in Chicago.

While Illinois residents like Thorne have the opportunity to register to vote in Illinois, these Iowans largely chose to caucus because they thought their vote would have a greater impact in their home state.

“I’ve been in Chicago for almost four years now and I never switched my registration to Illinois even once because I know that Iowa is a swing state and Illinois is a blue state,” Thorne said. “People talk about whether or not your vote matters and in Iowa my vote quote unquote matters a lot more than it does in Illinois.”

Most of those who attended Chicago’s satellite caucuses were young, either college students or new residents in the city. Barriers, such as childcare or sensory overload, didn’t appear to be an issue for those who attended.

“I was, like, trying to figure out how I was gonna get back to Des Moines between classes and having this Monday of classes, so it’s really nice that we are able to do this,” said Anne Teeling, a Northwestern student at the Humboldt Park caucus.

In addition to Iowans who have relocated temporarily, people traveling out-of-state, like Adam Yankowy, used the satellite caucuses to participate in the primary process.

Yankowy moved recently to Iowa but caucused at the Humboldt Park satellite.

“I’ve been looking forward to it and then realizing, ‘Oh, I’m out of town on business,’” Yankowy said, “I was gonna be really disappointed if I didn’t get to … be able to speak and support the candidate I want to support.”

(Meredith Melland, 14 East)

Sanders won Humboldt Park caucus

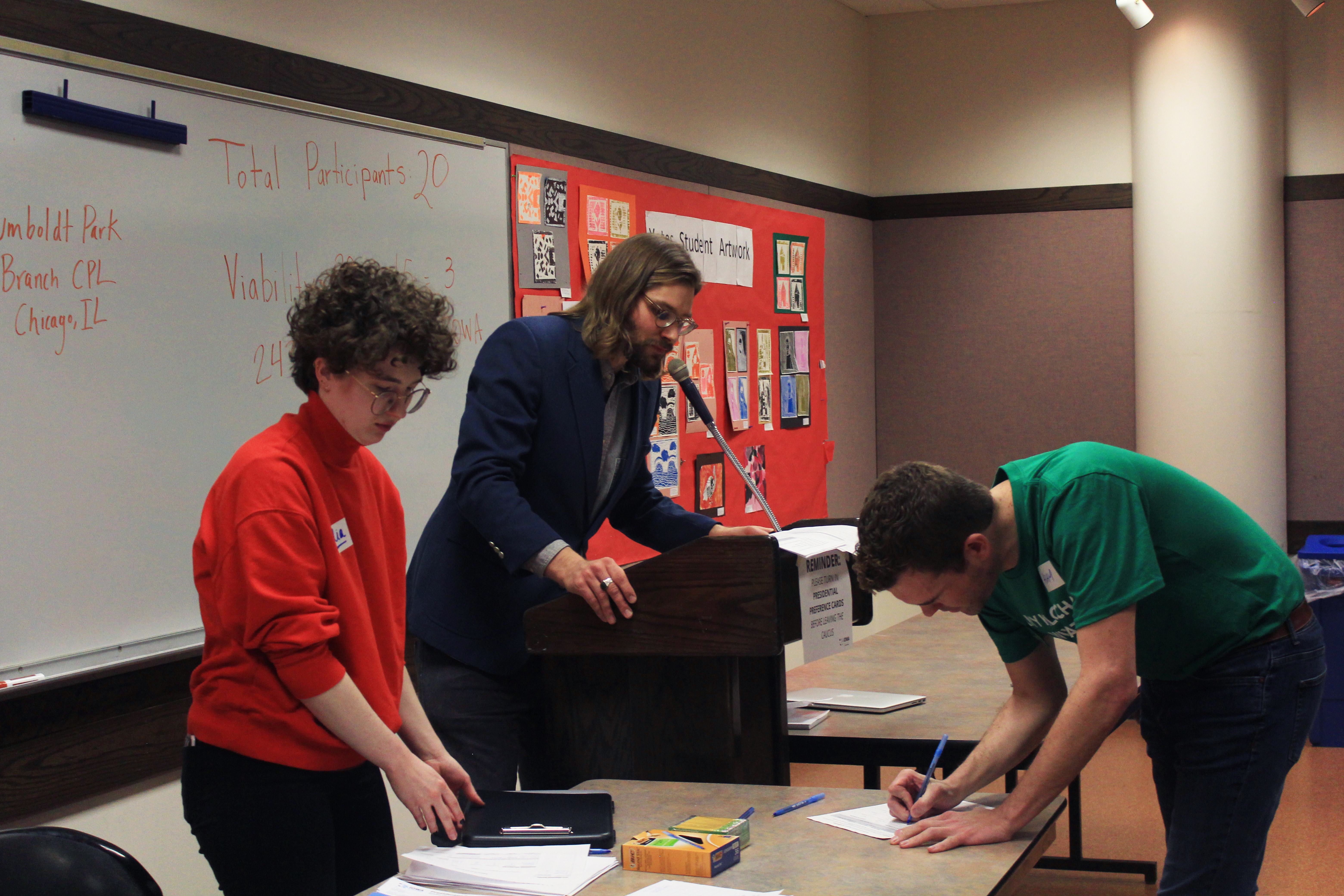

Registered Iowa voters and about two dozen outside observers trickled into a windowless events room lined with art projects and papers with candidates’ names in the Humboldt Park Branch of the Chicago Public Library.

“Even though it hasn’t started yet, the scale of this caucus is a lot smaller than when I caucused in the last election,” said Julia Anderson, a Des Moines native who moved to Chicago in August, while waiting for the proceedings to begin.

By the time the caucus was called into session, the room’s rows of black chairs were filled with 20 participants and slightly more observers. Unaffiliated onlookers joined press and advocates for the campaigns of Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg and Sens. Amy Klobuchar and Bernie Sanders in the back of the room.

“It’s pretty strange having observers here, you know, especially if they’re being very forthright about, like, what they want,”said Lindley Warren Mickunas, a Columbia College Chicago graduate student from Des Moines. “One group brought cookies that they wanted to put by their candidate, which is not allowed because it’s like bribery.”

Leah Barr, sitting with Anderson and Warren Mickunas, said that observers are allowed to campaign vocally in Iowa but usually do not.

“If somebody’s going to come to the caucus, they’re probably going to participate, unless they’re like out of town or media or something,” Warren Mickunas said, “but here, it’s like since we’re in somebody else’s state, it’s like, it’s much bigger.”

The caucus chair read the night’s guidelines, passed around a contribution envelope for the Iowa Democratic Party and held elections for the precinct’s leadership positions. Then, anyone who wanted to represent a candidate was welcomed to the podium to give a one-minute pitch. Barr spoke in favor of Sanders as his precinct captain, reading notes from her phone, and Yankowyshowed off his Klobuchar shirt while observers talked on her behalf.

Grace Gubbrud, a 21-year-old PR and advertising student at DePaul, spoke with another caucus-goer on behalf of Warren.

“The Iowa caucus is all about getting out for who you want to see,” Gubbrud said in an interview, “and I love Elizabeth Warren and I think she’s been a super inspirational public figure the past couple of years for a lot of people.”

Per caucus rules, Anderson — nominated and elected as the caucus secretary — established the viability threshold for the satellite, or the number of voters aligned with a candidate to equal 15 percent. If a candidate does not get 15 percent of support from people in the room in the first round, those participants must realign and go to a second choice or leave. In a group of 20, three people were needed to make a candidate viable.

With the rules established, the caucus-goers flocked to the part of the room with the Sharpied sign for their first choice candidate. Sanders was supported by 11 people, Warren by six and Klobuchar by three.

Afnan Elsheikh, a 20-year-old Northwestern student, camped out in the Sanders section.

“I canvassed for Bernie when I was, in the 2016 elections when I couldn’t vote,” Elsheikh said. “I just have always really liked him mainly because like, as a Black woman in America, he’s the only candidate.”

Because each group was viable in the first round, attendees signed presidential preference cards to commit to their candidates and avoid another round of standing around.

“I thought it was smooth and easy, it seemed like everyone was pretty much like prepared and committed,” Yankowy said. “I didn’t think it would be this fast, honestly.”

Lastly, the caucus leaders determined how many convention delegates each candidate would receive based on the preference group totals. The relatively small precinct only had four delegates to split up, so two were assigned to Sanders and one to Warren and Klobuchar, respectively.

This division demonstrates one of the oddities of the caucus process — Warren’s six voters doubled Klobuchar’s, but both candidates received the same number of delegates. But, thanks to the Iowa Democratic Party’s new transparency rules, the popular vote totals for each round will be reported along with the assigned number of delegates.

In non-satellite caucuses, delegates are converted at the county, district and state level and weighed into the state delegate equivalents: numbers proportionate to the amount of delegates in each precinct. But there’s confusion on how satellite delegates are being incorporated into this mix.

Sanders’ popularity in Humboldt Park was reflected in satellites across the world, putting him neck-and-neck with Pete Buttigieg for the top spot.

(Marissa Nelson, 14 East)

Warren won University of Chicago caucus

The dull murmurings of the gathered crowd at University Church of Chicago ceased as Hannah Gregor took the caucus stage.

Having received training and instructions ahead of time, she called the caucus to order as its temporary chair. In just a few short minutes, that title would change to “permanent chair” following a nomination and vote — part of the standard proceedings of a caucus.

The effort to organize the event was a co-effort between Gregor and University of Chicago student James Skretta. The process of securing the satellite caucus required two main physical factors.

First, the space in which the satellite caucus is held must be accessible, sizable enough to contain those attending and must be agreed upon prior by those to whom the space belonged.

Second, there must be enough people in the area interested in caucusing, something which Gregor said came hand-in-hand with the location.

“On a UChicago campus, it was pretty good because you could be like, ‘Well, there’s students here. So, they’re going to want to caucus because a lot of students are traveling and won’t be in Iowa,’” she said.

Per Gregor, projected numbers for the event included about 30 pre-registered voters.

In total, 24 voters attended the caucus and were joined by over 30 observers. Those in observation primarily consisted of reporters, campaign representatives and students from a University of Chicago class, with only a few outside observers.

Though each individual had their own reasons for showing up that night, a general overarching theme of choosing to witness and partake in democracy in action could be gathered.

“I think it’s important as part of the Democratic Party to come here and voice your opinion on the state of the race,” said Christian Pratt, a voter at the caucus.

Pratt explained that, as an Iowan, his choice to caucus arose out of a unique responsibility as an American voter.

“I think as Iowans we treasure the caucus experience maybe a bit more than the primary goers because, well, first off, we’re first in the nation,” he said. “And second of all, it is this caucus format rather than the primary, so we are expected to be kind of informed on what’s going on and being able to talk to the other candidates and other people voting.”

In fact, it was the novelty of the caucus experience that brought Susie Xu and her University of Chicago political anthropology classmates to stand in as observers.

“For a class, we’re each looking for different things,” she said. “We’re all trying to see how the democratic process works. And, my particular focus right now is to look for how [non-governmental organizations] and certain parties facilitate the democratic process that’s supposed to be state-run. So, I’m trying to see what the function of facilitators and press people are.”

For the most part, these facilitators played limited roles in a mostly quiet caucus that night. Presentations were given for a few candidates like Warren and Yang, and reporters gathered quotes and camera shots. It was among the voters themselves that most of the action took place.

“The fact that there is this viability threshold and, you know, groups that don’t have enough can go in and kind of discuss with other groups and decide who they eventually want to vote for,” Pratt said.

With a threshold of just four people per candidate, voters became persistent advocates for their candidates of choice, eagerly reaching out to those unsure or undecided voters in a hope to sway their stance.

Upon the closing of the night, Warren took the lead with 11 votes, Sanders second with 9 and Buttigieg third with 4. No votes were cast for any other candidate. Respectively, from that caucus, the candidates received two, two and one convention delegates.

Chicagoans learned about the caucus process

Though initially nervous about the satellite caucus, Thorne ended the event feeling positively about how it went.

“I feel happy about what happened, I think there was a baseline of respect that we had for each other. Even though we might not have known each other as well as, say, neighbors would, we were able to come together and talk about our candidate.”

However, the noticeably larger number of observers — candidate reps, press and curious Chicagoans — made Thorne feel a little uncomfortable. Typically, observers are children of Iowans caucusing or other community members, not outsiders “trying to understand this strange cultural event that is caucusing.”

“I’m exhausted,” Thorne said. “I’m literally shaking from the adrenaline. It felt a little bit like there were just a lot of people, outsiders looking in on this weird museum event thing.”

A caucus is a public event, and in Hyde Park, a light green line of tape divided the room in two, marking a boundary for where observers could stand.

Jonathan Johnson, a graduate student at University of Chicago, observed the event for class. He went into it with an open mind, curious about the process and how it is similar and different to primary voting.

“I thought it was an open, public way to do democracy that challenges the idea that democracy is an individual choice,” Johnson said. “And that democracy happens in communal places with many different people, some participating, some watching, some reporting, that reminds us that democracy isn’t something one person fights for but we all need to.”

Ultimately, Thorne said everyone involved — from observers to caucus-goers — were respectful.

“I’ve had some qualms about people from other states coming into Iowa and not really caring about Iowa as a state and trying to push their ideas on us, and I think this, even at the end of the day, did feel like an event with Iowans and about Iowans.”

Video by Natalie Wade, 14 East

Header photo by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

NO COMMENT