Podcast by Brita Hunegs

81-year-old precinct captain Myrt Bower’s rule over the Mount Vernon North caucus is poised and thoughtful.

She has the demeanor of a kind schoolteacher who you respect not because you have to, but because she deserves it — the type of leader who, when a middle-aged man giggles like a teenager after yelling “Go Biden” while she’s giving instructions, will quietly, but sternly, tell him to stop.

And he will. Sheepishly.

Myrt Bower, the precinct chair for Mount Vernon North (left) and David Osterberg. (Francesca Mathewes, 14 East)

The 237 eligible caucus-goers trickled into Mount Vernon High School Monday, February 3, signed in and headed to the designated section of the linoleum-floored cafeteria for their preferred candidate. Off the bat, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders had sizable camps of support.

There were several undecided, and a small but vocal group congregated for tech entrepreneur Tom Steyer, next to a couple of high school-aged students with a homemade sign for hedge fund investor and philanthropist Andrew Yang. Hugh Lifson, 82, planted himself firmly in the middle of the room, committing to Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet, who hasn’t made a televised debate since July.

Hugh Lifson, 82. (Francesca Mathewes, 14 East)

One undecided voter, Jennykaye Hampton, 47, wearing a “I f–king love voting” T-shirt, attended the caucus on her birthday, looking to be persuaded by the discourse.

“I want you to woo me,” she said to a passing Warren supporter.

Jennykaye Hampton, 47, talking to other undecided caucus-goers. (Francesca Mathewes, 14 East)

“The fact that I’d rather do this than go out with my family for my birthday says something,” she said. “It’s so fun. I walk out of here feeling invigorated. Listening to people helps me decide.”

Hampton, whose family immigrated from the Philippines, was on the younger side of caucus-goers and was one of the few people of color in attendance.

Mount Vernon is roughly 94 percent white compared to Iowa’s 90 percent. In 2016, 15.7 percent of Iowa’s population caucused and, similar to state demographics, 91 percent of caucus-goers this year were white, according to ABC News entrance polls.

The state’s lack of diversity is a big concern with Iowa going first in the primary process, outside of the massive late-result debacle.

As 7 p.m., the designated statewide caucus start time, drew near, people were welcomed into candidate groups with open arms and immediately began talking strategy. Attendees of the Mount Vernon North caucus know each other; they’re neighbors and friends.

“This goes back a long way. This is a chance for people to air their differences and talk about things that are real to them in a safe environment,” said Rich Hermann, 61. “We’re all leaning the same way… when your neighbor is for someone and you’re for someone else, you start to see that person differently.”

The process began with Bower, Queen of the Caucus, laying out the rules — they’re simple (they’re not).

The first count of caucus-goers and their respective candidates must reach 15 percent of the total attendees. This is called the viability threshold. Caucus-goers committed to candidates who don’t reach the viability threshold have to realign to another candidate, or leave.

After they’ve realigned, the final count is conducted. In this case, Mount Vernon gets four of Posey County’s delegates bound to viable candidates at the end of the second vote.

These county delegates are used to determine congressional district delegates which are then weighed into what’s called state delegate equivalents, or SDEs. SDEs determine how many delegates each candidate sends to the state convention and are proportional to the amount of delegates a candidate gets each precinct. The total SDEs, 2,107, are used to calculate the winner of the Iowa caucuses.

Compared to Illinois’ 184, Iowa has 41 national delegates allocated based on candidates’ share of SDEs. To win the Democratic nomination, candidates must win at least 1,990 national delegates.

This year, two other numbers are reported — the pre-alignment vote, the first vote determining who’s viable, and the final vote, the vote after realignment. This creates two results – the winner of the delegate vote and the winner of the popular vote.

There’s some strategy involved in the caucus process. Based on a new rule, those who caucus for a viable candidate in the first round are locked in and can’t realign. Phoebe Trepp, 38, caucused undecided in the first vote in case Sanders or Warren needed her vote to qualify for delegates.

The process is a bit complicated, and favors a caucus-goer’s second choice — making heightened campaigning in Iowa critical for candidate success.

Bower passed around a paper Happy New Year hat to collect money to fund the caucuses and from there, the first count began. A volunteer painstakingly counted the groups while attendees chatted about candidates’ electability, their platforms, their experience and, overwhelmingly, who can beat President Donald Trump.

“It seems more serious [than last primary] because of who we have in the White House,” said Jaimie Hanson, 52, who caucused for Buttigieg. “I’ve gone back and forth between so many of the candidates just because I want someone who can do it.”

This sentiment is widespread. In the caucus entrance polls conducted by ABC News, 62 percent of caucus-goers said beating Trump was their biggest priority.

In Mount Vernon North, Sanders with 42 committed, Klobuchar with 40, Buttigieg with 49, and Warren with 62 passed the viability threshold first round, leaving Biden, Steyer, Yang and Bennet supporters to realign or go home.

Precinct captains — who remarkably mirror their respective campaigns — have the chance to give their piece to the entire room and then everyone has 15 minutes for realignment persuasion.

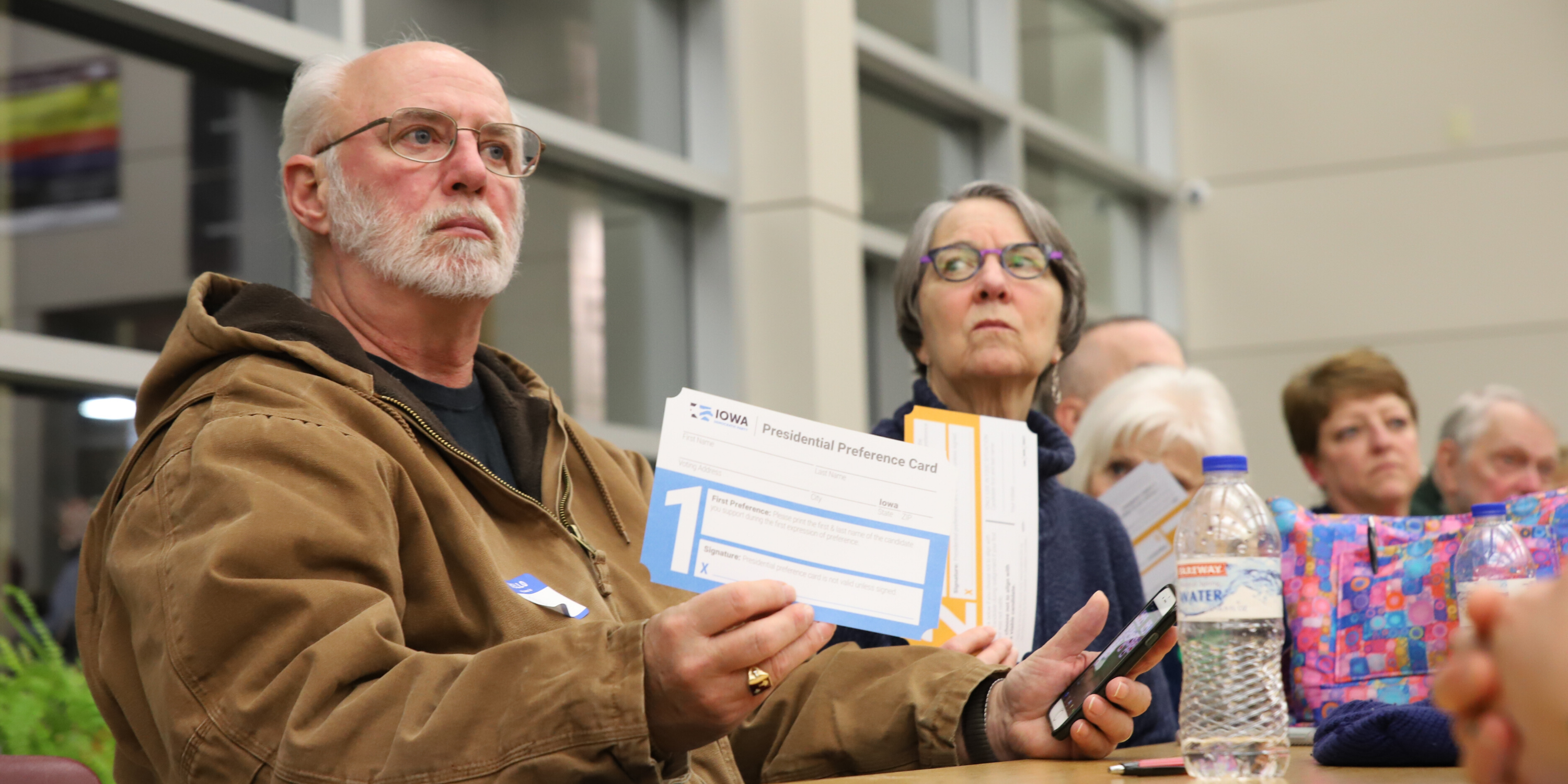

(Francesca Mathewes, 14 East)

“I know half the people in the group,” said David Osterberg, 76, a former politician who served in the Iowa House of Representatives and Warren’s precinct captain. “I’m going to use that as soon as they’re not viable.”

Osterberg, like Warren, tried to toe the line between charisma and statistics. Sanders’ precinct captain, like much of his base, was young, passionate and yearning for health care. Klobuchar’s, after making a joke about not being as crazy as the socialists, seemed pragmatic and a bit nervous. Buttigieg’s was a newcomer, a San Diego transplant without much caucus experience. Yang’s was an 17-year-old kid who just wanted to tell people to vote for someone who aligned with their values.

Graham Bradbury, 17, will turn 18 in time to vote in the general election. He was one of just a few Andrew Yang supporters before realigning with Bernie Sanders. (Francesca Mathewes, 14 East)

And Lifson gave an impassioned speech for Michael Bennet, airing his qualms about every other candidate one by one — some didn’t care enough about education, others not enough about people of color, and Yang’s jokes weren’t funny enough.

During the 15-minute realignment period, the echo of conversation filled the room as caucus-goers sat down with the nonviable and undecided to give the case for their candidate – phones were grabbed to fact check, eye contact was intense, someone was standing on a chair.

The final count: Warren with 66, Buttigieg with 55, Klobuchar with 46 and Sanders with 44. Some caucus-goers remained with non-viable Biden, Steyer and Yang.

(Francesca Mathewes, 14 East)

Bower watched the entire ordeal, like a sort of omniscient caretaker, making sure nothing got out of hand.

“We’re here to respect each other,” she said. “We’re not here to use a campaign-style rally to get people over to a [different] campaign. We’re here to get into groups and use persuasion.”

(Francesca Mathewes, 14 East)

Bower has a long history with the fated, and under fire, Iowa caucus. She’s attended almost every caucus since 1976 and could cite almost every candidate.

The caucus as we know it today first took place in 1972, after the nightmare that was the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The Democratic National Party tore themselves apart over Vietnam and Civil Rights through riots and assassinations. Party leaders decided the process needed to change to be put in the hands of grassroots voters.

Iowa Democrats were frustrated with the state convention’s control by party bosses, so they broke down the caucus into districts. They calculated how long it would take them to calculate votes on their antiquated mimeographs from district to county to state, and they accordingly pushed back the date, making Iowa first.

The implications are heavy — only one candidate who’s placed lower than third in the Iowa caucuses has gone on to win the Democratic nomination. The Iowa caucus campaigns and results are often a predictor of how candidates will perform the rest of the primaries in both the polls and on the ground.

Candidates don’t have to win to be considered a winner. If they do better than expected, or, as of this year, receive the popular vote, they still can gather enough momentum to carry through the rest of the primaries (see Bill Clinton). Candidates can also now use the popular vote from the first alignment to gauge if they’re first or second choice.

The whole ordeal has become a spectacle. Candidates and organizers swarm to Iowa weeks before the caucus date to gather grassroots support.

“It’s amazing to be able to have a voice early on and to be seen and heard through the process rather than a vote on Election Day,” said Hanson. “You’re more part of the process.”

Iowans get firsthand access to campaigns, some see several candidates throughout the campaigning process and others have close relationships with organizers.

This engagement is built into Iowa caucus-goer culture.

“I think people here take it very very seriously and are deeply involved and very conflicted,” said Christine Flavin, 67.

Osterberg trying to sway Lifson during the second alignment. (Francesca Mathewes, 14 East)

Jaimie Hanson brought her kids, 8 and 11, with her, hoping to spur political conversation.

“This is powerful for them to see,” she said “They caucus with us because we don’t want them to miss out.”

This early commitment is common throughout Iowa. Katherine House, who attended the Klobuchar rally the day before, said her 10-year-old son was able to name every single Republican and Democratic candidate in the 2008 primary.

“Iowans take it very seriously,” she said. “We want to know what they’re about.”

Conversations in Mount Vernon that evening were civil, but serious. They balanced pointed remarks on immigration between lighthearted neighborly jokes.

Hampton’s first year caucusing in 2008, she remembers being “bullied” for supporting Obama while her best friend supported Clinton.

“But it was good,” she said. “It was this discourse that we were having that it was okay to have these decisions and to be thinking differently.”

The advantages of this discourse are curtailed by Iowa being predominantly white, as well as the fact that caucuses are not entirely accessible and many feel it lends itself more to the politically engaged. Hampton noted that despite Mount Vernon’s minority population growth, she didn’t see it reflected in the caucus.

“There should be a lot more people here,” she said. “It’s for people who are engaged…we could do a better job of making it more equitable.”

Caucuses succeed in being a collaborative, community-oriented and civil space for political discourse. But they’re fairly active, one much easier to participate in if you can stand. And, if you want to caucus, you must arrive before 7 p.m., no later.

“I think it needs to be reformed. I don’t think it’s fair to a lot of people who can’t get here,” said former educator John Anderson, 74.

While walking laps at a local church gymnasium that morning, Andersen met a woman looking to vote, not understanding the limitations of the caucus. She worked nights, and wasn’t able to attend.

“There are lots of people who don’t understand, and these are people with good hearts and good intentions,” said Juanita Andersen, 72, Steyer precinct captain and John Andersen’s wife. “It makes you want to cry … Apparently they had some caucuses that were designed for people who did have to work, but somebody like this lady probably didn’t know that. If they really want Democrats to come out, let’s not make it so damn difficult.”

Not to mention the tallying system is complicated and, if you play your cards right, can result in a statewide coding error and subsequent national critique.

Whether Iowa should or should not be first is up for debate. But there is one thing that rings true in the eyes of the Mount Vernon North caucus-goers.

It’s chaotic and a whole lot of fun.

“This is why I love it,” Hampton said, looking around at the chatter.

“I think it’s a ball. I think it’s fun. I like the direct neighborly aspect of it,” said Lifson before picking up his cane and making his way over to realign to Klobuchar from Bennet, who, with one vote, did not reach the viability threshold. “But, I understand its limitations. There’s serious democratic issues.”

Audio file created by Brita Hunegs

Header photo by Francesca Mathewes

NO COMMENT