When I first pitched the question “What do you think of when you think of Freemasons?” this past May during a newsroom meeting, the unanimous answer that was given by the 15 or so people present was “the Illuminati.”

I began research for this article by posing the same question to other friends of mine at DePaul. Not everyone knew what the Freemasons were, but those who did gave similar answers that they were some cultish world order.

I did find one person at DePaul who was able to get close with their answer, who recognized the Freemasons as a fraternity not much different than the one he was a part of. However, he was the one exception.

My quest to find out what DePaul students thought of the Freemasons came out of a mild case of culture shock for me. I grew up in Springfield, Illinois, and received most of my schooling just north of Springfield in Athens (pronounced “AY-thenz”), Illinois.

Growing up, the Freemasons still held the notoriety of being a mysterious organization whose secrets must never be shared to the world, but they weren’t some sinister sect of the Illuminati. They were simply a group of community members doing some form of charitable work for the greater good, be it raising money for good causes, feeding the homeless or something else.

Masonic temples from where I am from are often located in areas of high public visibility. In Athens, the Masons meet in a temple located along the block-long corridor that made up the “downtown” district. In Springfield, the Ansar Shriner Temple shines golden and gleaming with a flashy fez-adorned sign just blocks from the capitol.

“Warren G. Harding Wearing a Shriner’s Fez,” black & white film negative. (Photo: Library of Congress)

I asked my friends back home, “What do you think of when you think of Freemasons?” About a fourth of them had no idea that Freemasonry was a thing. However, those who did know gave answers of veterans, police officers, firefighters or (my favorite) an angry old man at an estate sale.

These descriptions were then followed by ideas that the Freemasons were some form of new world order, but the regional differences in the answers I was given remained. Back home, Freemasons may still have been perceived as akin to the Illuminati, but they were first and foremost community members.

For a metropolitan area as sprawling and diverse as Chicago, it came as a shock when I began to realize just how unaware the urban communities I encountered seemed to be when it came to Freemasonry. I then realized that I had never seen an active Masonic temple in the city or the red fez of a Shriner among the throngs of heads milling about the Loop.

However, I knew they existed in the city. After all, I had taken the ‘L’ and ridden past the Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center on numerous occasions. I also knew that the Bloomingdale’s on the corner of Ontario Street and Wabash Avenue was a converted Shriner temple (a body of Freemasonry). The building is soon to be converted yet again into another form of retail space later this year.

I knew that the presence of these two structures meant that the Masons weren’t completely absent from Chicago’s social tapestry. Thus, the question at hand for me wasn’t “Does Chicago have Freemasons?” but rather “Where are Chicago’s Freemasons?”

To begin the quest to answer my questions over Chicago Freemasonry, I first went back home to Springfield to learn more about what Masonry is and how Masons operate within the communities I grew in.

What is Freemasonry?

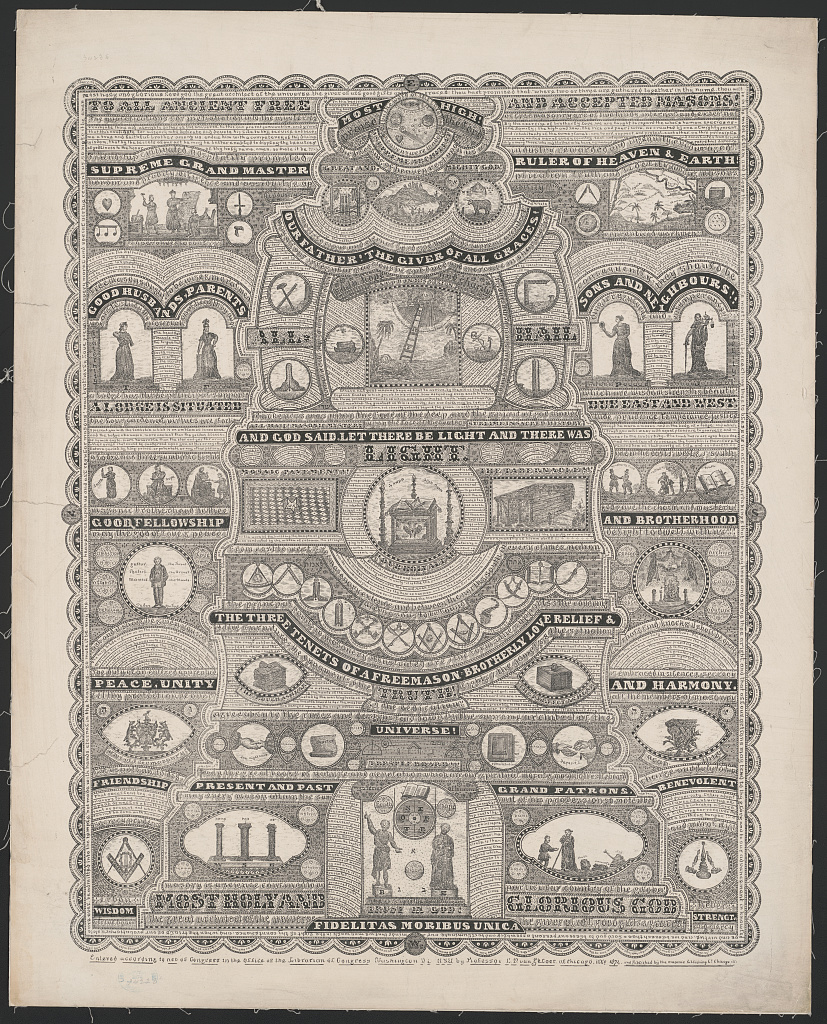

“To All Ancient Free and Accepted Masons,” lithograph. (Photo: Library of Congress)

I found myself at the doors of the Springfield Masonic Center, home to Springfield Lodge #4 A.F. & A.M. (The “A.F. & A.M.” part stands for “Ancient, Free and Accepted Masons.”)

The Springfield Masonic Center operates as a Masonic temple — the physical space in which Masons meet. This is distinguished from the Masonic lodge, which can be used colloquially in smaller lodges to refer to their meeting space but formally refers to the individual membership units, e.g., Springfield Lodge #4, which utilize the temple’s space. Both differ from the Grand Lodges, which are found in every state and oversee all Masonic operations within the states in which they are located. Internationally, they oversee the Masonic lodges of a specific country or region.

At Springfield Lodge #4, I was greeted by Bill Graber and Steve Walls.

Graber, 59 years old at the time of our interview last June, first joined Freemasonry in his early teens through the Order of DeMolay, an offshoot of Masonry catering to boys ages 12 to 21. Prior to that, he was indirectly involved in Masonry through his mother, a member of Eastern Star, a sisterly body within the brotherhood of Freemasonry. Graber served as a past master (the head of a Masonic lodge) in 1989 and recently retired from his post as secretary at Springfield Lodge #4 in 2019 after serving 20 years in that role.

Walls joined in 1996, later into his life. The son of a Freemason, he served at Springfield Lodge #4 as master in 2000 and as treasurer from 2003 until his appointment by Graber to the office of secretary in 2019. Throughout his years in Freemasonry, he has served on various committees for the Grand Lodge of Illinois (which oversees all lodges in the state) and as secretary to the Valley of Springfield (which represents the northern jurisdiction of the Masonic York Rite) for 12 years. Currently, in addition to his role as secretary at Springfield Lodge #4, he is serving his 13th year as a Grand Lodge officer, currently occupying the post of assistant grand tyler (the doorkeeper of a Masonic lodge).

I began the interview by jumping right in and addressing the “Illuminati” response I had received from my Chicago peers. Graber was the first to address this icebreaker.

“Tongue in cheek, do you know what ‘Illuminati’ means?” he asked.

I responded that, apart from its use in pop culture as a term referring to a mythical world order , I really had no idea.

“‘Enlightened One’ — it just means that you have received light,” he said. “In the Masonic fraternity, we call knowledge ‘light.’”

Freemasons make use of this definition of Illuminati when speaking of those within the organization. Though not consistent across the organization, Freemasons will refer to their fellow brothers as “Illuminaries,” i.e., “those who have received the light.”

Graber was careful to point out that the “knowledge” received through Freemasonry is far from the deep, dark, underground system of secrets and global domination that the mainstream paints it out to be.

He explained its true encompassment simply: “All we do is take good men and give them something to make them better. That’s all we do.”

He expressed great frustration over the portrayal of Freemasonry in the media, including those making the organization out to be one rife with secrecy.

“There are no secrets in Masonry,” he said. “We’re not a secret.”

However, this expressed non-secretive nature of the organization does not mean that Freemasonry discloses every attribute of its rituals and proceedings to the public.

“There is nothing that I can’t really tell you about it,” Graber said. “Except, there are things that I won’t tell you. Not that I can’t, I won’t because I’ve sworn to say that that’s what is my way of being able to recognize another brother.”

Returning to Masonry’s purpose of taking good men and making them better, Graber expanded on what that means and how it is accomplished.

“It’s just giving you one more little piece of something that will help you live a better life; help you interact with your brother and your community, your friends, your neighbors, your family even,” he said. “It’s just one more little lesson that can help you out. That’s all it is.”

He explained how this process works, though he would not discuss exact details.

“You have degree work, which is basically the initiation process, and you progress through the different degrees,” he said. “Something is portrayed to show you the lesson, a lot of allegory, a lot of that type of thing. You’re taken on a symbolic journey of life, you encounter things that should cause you to think twice about doing something bad.”

I had heard this concept of a Masonic “journey of life” before during a tour given to my scholastic bowl team of Van Meter Lodge #762 A.F. & A.M. in Athens (the Masons were big donors to our school’s scholastic bowl program and had hosted us for dinner at the lodge). I had inquired about the meaning of the below lithograph, a large version of which hung in their main meeting space.

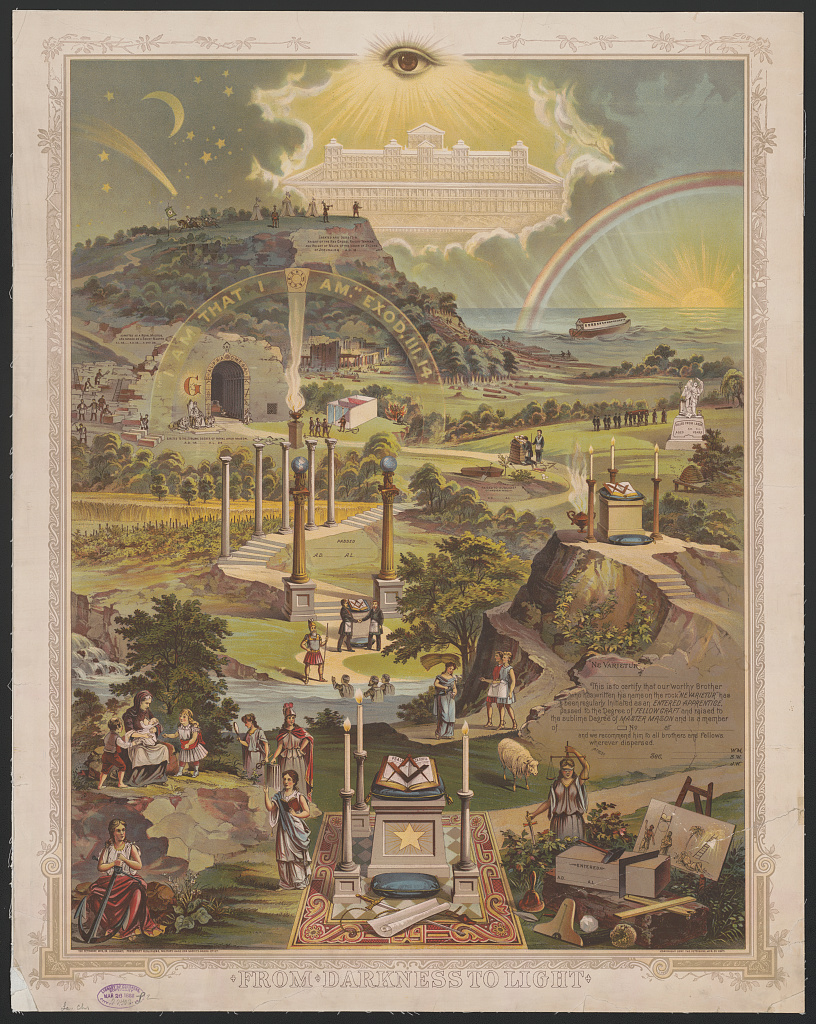

“From Darkness to Light,” chromolithograph. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Though the exact meaning of the symbols and allegories contained in it are undisclosed by the Masons, a basic understanding of its imagery was given to me during my tour of Van Meter Lodge #762. Below is a paraphrased version of the interpretation by the Phoenixmasonry Masonic Museum and Library, which is similar to the one I received at Van Meter.

Titled “From Darkness to Light,” it alludes to the concept of the receiving of the light, i.e., “knowledge,” that was explained by Graber earlier in this article.

At the top seated above Solomon’s Temple is the All-Seeing Eye looking over the Mason’s path. Stylized elements of the meeting room — like the columns and book stands — stand as waypoints and symbolic inclusions of Judeo-Christian and secular origin serve as reminders of Masonic principles.

Along the way, the names of important milestones may be found with space to sign and date upon their completion. Below is a narrative of what these are and how one progresses through Freemasonry.

The Journey of Life

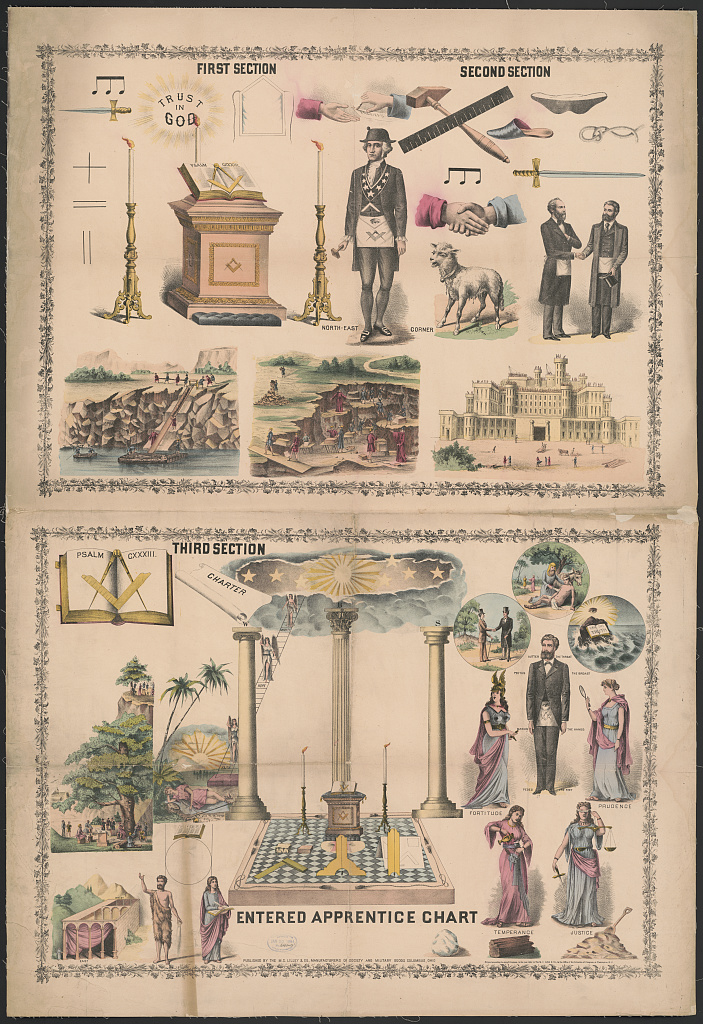

“Entered Apprentice Chart,” lithograph. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Back at Springfield Lodge #4, Walls explained that a Mason’s journey is measured through a system of three degrees: Entered Apprentice, Fellow Craft and Master Mason.

Though he said that some higher degrees may be “conferred” on certain individuals, a third degree Master Mason is the highest recognized degree achievable. All Master Masons are viewed on an equal level, regardless of any conferred degrees.

Before any work on degrees may begin, one must first come to the Masons with free will.

“We don’t solicit for membership, we don’t go out on membership drives, we don’t go out and, you know, beat the bushes [and say] ‘Come on, you need to become a Mason,’” Graber said. “We might suggest to somebody that, you know, if you ever decide you’d like to join, call me. I’ll help you. But, I’m not going to ever ask you, and no Mason will ever ask a person to join. If they do, they’re wrong.”

“If you want to join Masonry, you’re going to have to ask somebody to join,” Walls said in response to Graber.

The idea of free will is one that is echoed time and time again during a Mason’s journey.

“One of the first things you will hear: ‘Of your own free will and accord,’” Graber said. “It’s in every degree we do: ‘Of your own free will and accord.’ We are never forcing anyone into this organization or forcing you to learn anything or forcing you to become a part of it. If you choose not to, walk away.”

That isn’t to say that the lodge doesn’t provide some poking and prodding along the way.

“There might be times when you have shown interest, and you’ve gotten yourself started,” Graber said. “And, we think you’re getting lazy and don’t want to learn something or get lazy and don’t want to progress up the next degree. We might nudge you a bit, but we won’t force you.”

Graber went on to explain the prevalence of this nudging within families.

“If you got somebody in your family, that’s amazing,” he said. “And, they find you joined, guarantee you’re going to get harassed forever until you finish. It’s all done in friendliness, brotherhood.”

With or without friendly nudging or brotherly pestering, Walls said that the process of completing all three of the degrees can take as little as one month but is typically done in four to six. However, the Masonic journey doesn’t end there. Upon reaching the Master Mason degree, individuals are then given the choice to join a rite. While many different types of rites exist, Scottish Rite and the York Rite are the two most common.

“Scottish Rite Temple, Washington, D.C.,” glass negative. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Rites give Masons the opportunity to further explore the organization’s teachings, almost like a Masonic equivalent to receiving a college education. The Scottish Rite starts at the level of fourth degree Master Mason and ends at 32nd degree Master Mason. The York Rite, on the other hand, is split into a Northern and a Southern jurisdiction and is inclusive of three levels: Chapter, Council and Commandery.

In addition to joining a rite, those with the Master Mason degree also qualify to join various Masonic bodies. The most publicly recognizable of which are the Shriners, known outside of Masonry for their children’s hospitals, circuses and fun-loving antics. These bodies work alongside each other under the greater umbrella of Masonry and generally have a central cause they support such as the Shriners’ children’s hospitals or the Scottish Rite’s children’s learning centers.

Tradition and History

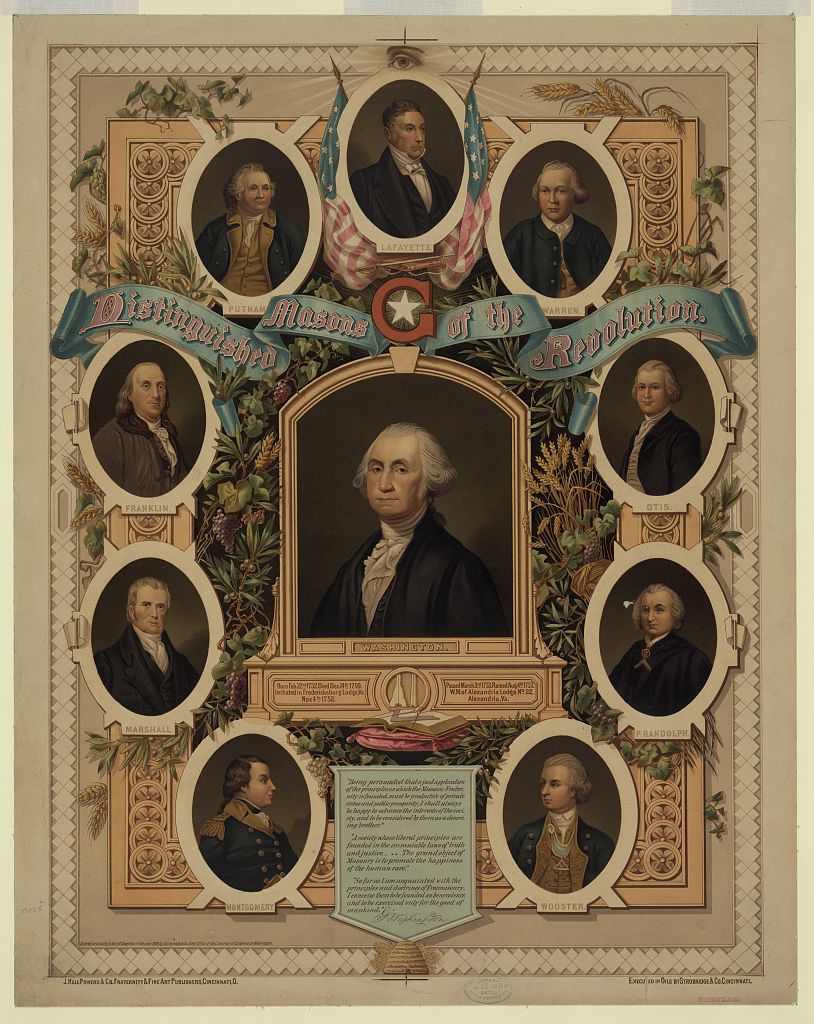

Distinguished Masons of the Revolution,” chromolithograph. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Returning to Springfield Lodge #4, Graber boasted that it stands as the longest continuously operating lodge in Illinois.

Founded in 1840, its list of original members at the time of its charter most notably includes the name of Stephen A. Douglas, who famously debated and lost to Abraham Lincoln as the Democratic candidate during the 1860 presidential election. Graber expressed that this tie to Douglas leads him to consider Springfield Lodge #4 as a “crown jewel,” and stressed the lodge’s pride in having him tied in with their history.

According to Jeffrey Norman Lash in A Politician Turned General: The Civil War Career of Stephen Augustus Hurlbut, Douglas also served as the first grand orator (a post responsible for research, education and degree paperwork) to the Grand Lodge of Illinois in 1840. A painting of him in full Masonic regalia (shown below), in addition to the original signed charter of Springfield Lodge #4 with his signature on it, are displayed in the lobby of the Springfield Masonic Center and in the office of Springfield Lodge #4, respectfully.

(Justin Myers, 14 East)

Regarding the founding of Freemasonry as a whole, Graber explained that it’s a history that goes much farther back than Douglas’s time.

“We know it to be traced back to the building of King Solomon’s Temple in the Bible,” he said. “We know that because of tradition. Do we know it for an absolute fact? No, we do not. Can we historically prove it? No, we cannot. Do we use it as part of our teachings? Yes, we do, because it is tradition.”

He went on to explain that the earliest concrete historical date for the founding of Freemasonry is the year 1717, during which the Grand Lodge of England was first established.

The unorganized concept of Freemasonry, however, began much earlier. The organization grew out of medieval stonemason guilds, which operated as an equivalent to today’s workers unions and inspired the name “Freemason.” During this pre-founding period, Masons were being initiated and lodges existed, but they did not have a central entity to which they answered. It is thus best to see 1717 not as the birth of Masonry as a whole but rather as the start of the modern idea of organized — rather than unorganized — Masonry.

From there, it spread around the British Isles before landing on colonial shores in cities such as Boston and Philadelphia, where it spread among the colonies in America. Famous early American Freemasons include those pictured in the lithograph above such as George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. Masons from more recent American history include Buzz Aldrin, Jesse Jackson Sr., Charles Lindbergh and 13 other U.S. presidents.

Freemasonry has since spread to circumnavigate the globe with 213 Grand Lodges spread across more than 100 countries and territories worldwide each representing dozens upon dozens of smaller, local lodges like Springfield Lodge #4. Famous Freemasons of international fame include Mozart, Sir Walter Scott, Simón Bolívar and Napoleon’s four brothers.

Currently, the organization has approximately six million members around the world.

According to the Masonic Service Association of North America, the 51 Grand Lodges in the U.S. make up roughly 18 percent of the world’s population of Freemasons. In 2017, the top three states with the most Masons were Pennsylvania with 97,822, Ohio with 80,602 and Texas with 70,590. Illinois came in fourth with 55,210.

Women and Masonry

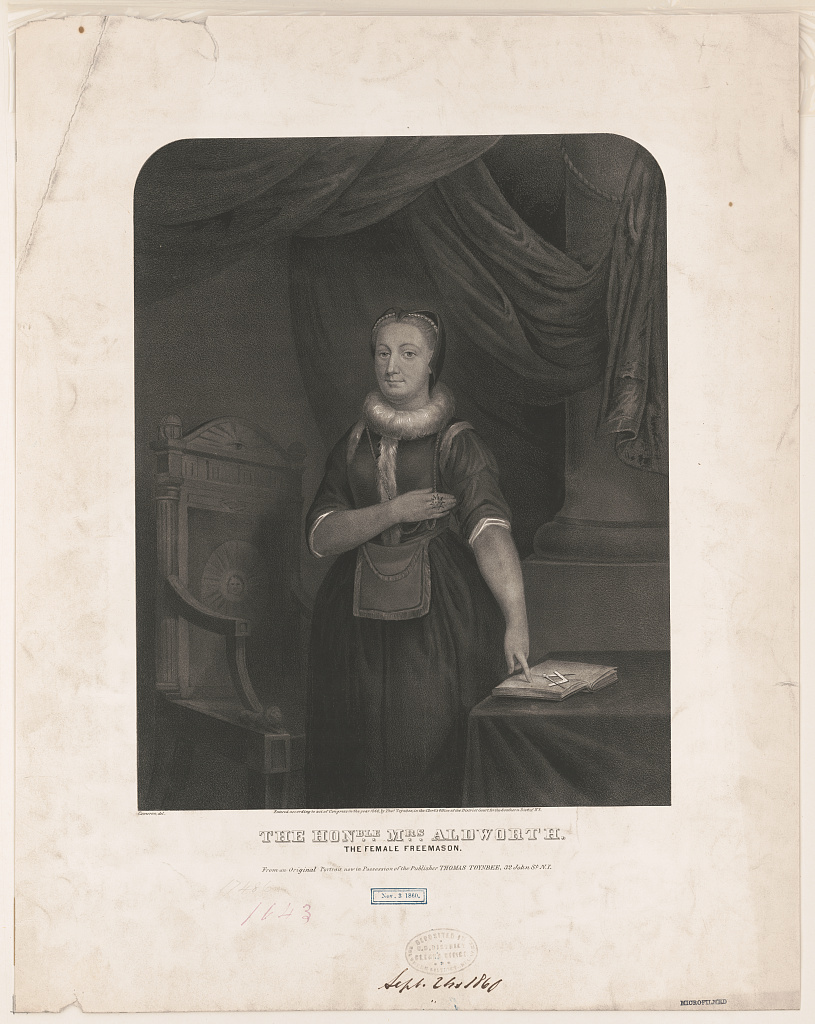

“The Honble Mrs. Aldworth: The Female Freemason,” engraving. (Photo: Library of Congress)

While this article focuses on the fraternal order of Freemasonry, women have played important and integral roles on levels in the past and present history of Masonry.

The first recorded instance of a female Freemason took place around the year 1710 when Elizabeth St. Leger Aldworth (pictured in the engraving above) was initiated as a fraternal brother by chance. According to legend, after falling asleep in the room next door to a Masonic meeting held at her family’s estate, she awoke, came into the meeting room after hearing voices coming from it and saw the lodge’s proceedings firsthand. It was this unintended acquisition of her personal knowledge of Masonic proceedings that led the lodge’s members to initiate her as Brother Elizabeth St. Leger, later Brother Elizabeth Aldworth following her marriage.

The “Lady Freemason” would serve as a brother until her death in 1775.

Though women are no longer officially initiated into the fraternity of Freemasonry as with St. Leger Aldworth’s case, the Masons offer multiple opportunities for their involvement.

Various orders related and tied to Masonry offer female-run opportunities for women to join the organization as members, the largest of which is the Order of the Eastern Star. Others include but are not limited to the Order of the Amaranth and the White Shrine of Jerusalem for women and the Order of the Rainbow for Girls and the Daughters of the Nile for girls and young ladies.

Within Freemasonry, women retain important support roles as staff members of lodges. Additionally, Graber and Walls explained that the wives or partners of those working through their degrees often act as important sources of support during the process, rehearsing the ceremonial proceedings with their significant others.

Thus, while Freemasonry is a fraternal organization, women may be found in many different roles under the umbrella of its reach as an organization. Thus, though this article revolves around the fraternity of Freemasonry, it is important to be informed that women do play a part both in Masonry and its sister orders.

In Old Chicago

“The Masonic Temple, Chicago’s Great Sky Scraper, Randolph and State Sts.,” stereogram. (Photo: Library of Congress)

It is at this point in my narrative of my quest to unravel the mysteries of Freemasonry that I break free from the foundational grounds covered at Springfield Lodge #4 to directly address the question central to my search: “Where are Chicago’s Freemasons?”

Freemasonry entered the community framework of Chicago in 1843. It is in the city’s much boasted architectural heritage that the mark of these early Chicagoan Freemasons may still be found.

The most notable extant example of these early Freemasons may be found at the Chicago Water Tower, whose northeast corner contains a Masonic cornerstone, a homage to the Masons who oversaw its design and dedication. The aforementioned Bloomingdale’s (built as and still called Medinah Temple), completed in 1912, and the InterContinental Chicago (formerly the Medinah Athletic Club), completed in 1929, stand as more contemporary reminders of the influence of Freemasons on the city’s architecture.

However, perhaps the grandest example of Masonic architecture to ever exist in the city is one that no longer dots its landscape: the old Masonic Temple Building.

Pictured in the background of the stereogram above, the Masonic Temple was located at the northeast corner of Randolph and State Streets and was completed in 1892. It was revolutionary for its time. Designed by Burnham and Root, this mammoth structure measured 302 feet high and in 1895 became the city’s tallest building following the removal of the clocktower from the old Board of Trade Building. Its vast system of elevators, monumental size and extensive electric lighting was unparalleled for its era and praised by the masses.

However, history was not kind to this groundbreaking edifice. In 1939, the Masonic Temple was demolished, as it was deemed to be economically unsustainable.

As of today, only two “mainstream” Masonic temples currently exist to house all of the city’s lodges — the Mont Clare Masonic Temple and the Jefferson Masonic Temple. These are found outside of the city’s central business district, i.e., the Loop, and fall outside of a nine mile radius from the city’s point zero. One Grand Lodge, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Illinois, is closer and falls within a six mile radius of point zero (more on Prince Hall Freemasonry and how it differs from “mainstream” Freemasonry is found later in this piece). It houses Prince Hall Lodge #52 in addition to the Grand Lodge.

“At one point, there were so many lodges within the neighborhood that you could live in any neighborhood and within a few block radius you would have a lodge to walk to,” said Robert Harvey, secretary at Hesperia Lodge #411 in Chicago.

So, what happened?

“The people from World War II, that was the big spike in Masonry in Illinois,” Harvey said. “Throughout the country, actually, there was a huge spike in membership after the war. And, as people moved out, got less active or died off, that caused them to sell off the building.”

A steady increase in membership occurred in the ‘40s and ‘50s as a result of the camaraderie experienced by those who served in World War II. Veterans returning home sought out ways to continue the framework of brotherly fellowship they enjoyed during their time in service, turning to fraternal organizations such as Freemasonry to fill that desire.

During this peak, Masonic membership in the U.S. soared from 2.8 million members to over 4 million. However, this would be short lived.

As Harvey stated, the fraternal zeitgeist following the war eventually wore out, and people moved away from their lodges without rejoining another, died or lost interest in continuing the work needed to be an active Mason. Socially, fraternal organizations fell out of favor in the latter half of the 20th century.

As a result, the physical presence of Freemasonry in many of Chicago’s communities faded out of existence in the lives of many of its residents as membership numbers continued to decline following the spike. Currently, there are nearly 1.1 million Freemasons in the U.S., according to Masonic Service Association of North America.

Another reason for the comparative lack of prevalence of Freemasonry in Chicago as opposed to what I grew used to in Springfield might be the social framework of community life itself.

“It’s more rooted [south of Chicago],” Harvey said. “People are there forever, and families are known. And, I think that’s where strong [community] presence is in Southern Illinois — or Illinois south of Chicago.”

While family ties to Masonry do exist in Chicago, Harvey described Chicago’s sense of community overall as being “more transient” when compared to the rest of the “rooted” communities found elsewhere in the state. In brief, city dwellers are simply more mobile than their rural counterparts.

A similar phenomenon was noted by Graber at Springfield Lodge #4.

“I’ve seen a lot of small lodges have a lot of drive and can actually outdo…some of the bigger lodges, bigger towns because they just have a base of people around there that know that they’re there,” Graber said. “Sometimes, in the bigger towns, the biggest problem is the fact that I think people just don’t know about them.”

Though, despite its faded presence, Harvey said that from his viewpoint, Freemasonry is experiencing a revival in Chicago — something he doesn’t take for granted.

“We’re really lucky in Chicago with the upswing we’ve been having,” Harvey said. “There’s actually a member of our lodge who has the capacity to open a new building. He’s talking about building a new temple.”

Per Harvey, in order to construct a new temple, it must be proven that there is sufficient interest and an ample enough membership body in order to construct one. Requirements to start new temples follow the process to start a new lodge set by the Grand Lodge of Illinois.

To begin a new lodge or temple, it is required that at least 20 master masons sign a petition, confirm ownership or approved use of a new location and prove that the candidate for the lodge’s worshipful master (the leader of a lodge) is certified to run Masonic ceremonies.

Thus, having the ways and means to open a new temple reflects growth and financial stability in Chicagoan Freemasonry.

So, in the 21st century, what’s drawing people to Freemasonry?

The Modern Appeal of Masonry

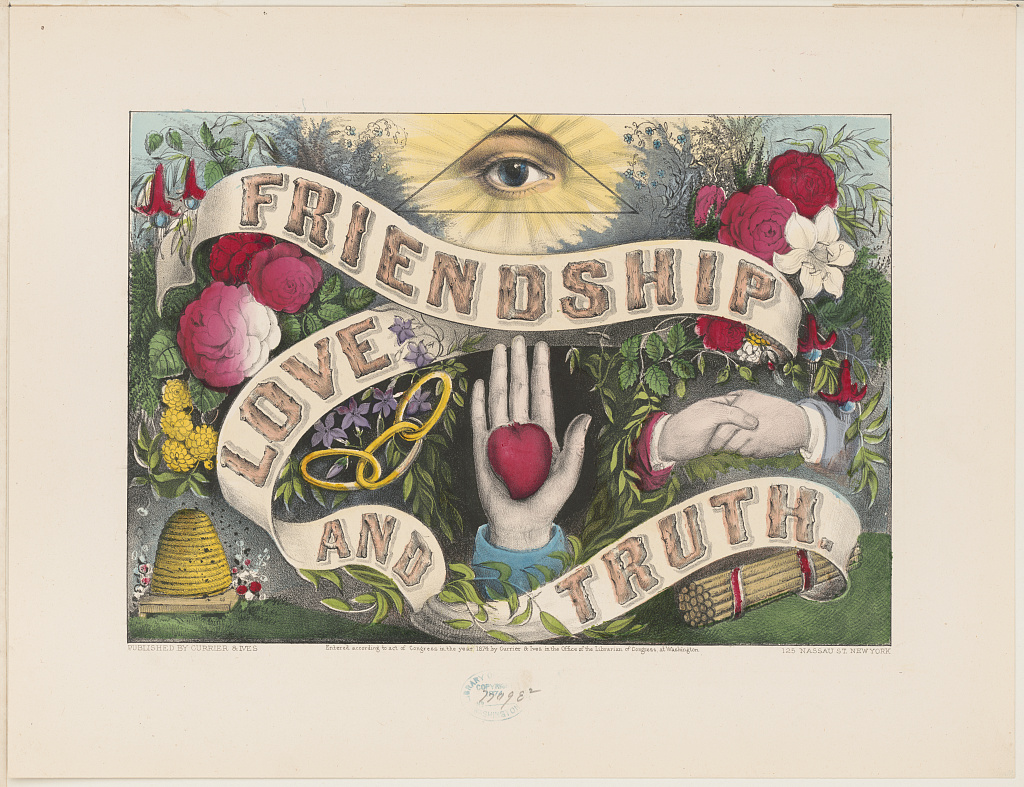

“Friendship, Love and Truth,” lithograph. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Before delving into that question, I would first like to introduce the final character in the story of my quest: Wayne Spooner.

Spooner serves as the chairman of the membership development committee for the Grand Lodge of Illinois as well as the lodge education officer for Hesperia Lodge #411.

“More specifically, for many people — especially on the younger side — [the draw] is the concept of self-improvement,” he said. “So, that has resonated very well.”

Additionally, the knowledge of Freemasonry being a true fraternity and other aspects such as its focus on family have drawn people in. One of the reasons these attributes of Masonry are just now starting to catch the attention of new members is a shift in how Masons present themselves.

One of the developments within the last five years in Freemasonry that Spooner said he has observed as a member of the Grand Lodge’s membership development committee is the rise of young people seeking out trustworthy information on Masonry.

“That’s being done because there’s a number of Masonic organizations that have decided to say, ‘Hey, there’s a whole lot of…entities out there in the whole cyberspace internet that’s taking on the trying to tell our story,’” he said. “How about (A) that’s not even remotely accurate? How about we need to because that’s where people are going for good information?”

In response, various lodges and organizations within Freemasonry have risen to the challenge of being better representatives of the organization and its positive attributes.

“Each lodge of Chicago is seeking different ways to reach out to the general community,” Harvey said. “Like, our lodge, we do a yearly thing where we do Square Roots Street Festival…and act as an information tent.”

Again, the Masons stressed that they do not recruit people, instead relying on one’s own free will to join the organization. The purpose of these in-person endeavors is not for them to approach the community but rather to provide an opportunity for the community to approach them.

“We’re there [at the festival] in case people are interested and also [to put] a face on Masonry,” Harvey said. “A lot of people think of Masonry as, ‘Oh, these guys meeting in this dark little temple.’ You know, it’s mysterious, right?”

Apart from seeking the truth about information on the “mysterious” Freemasons they found online, people come to inquire about Masonry for many different reasons.

To give examples, Spooner explained how his own interest in the brief mentions of Freemasonry principles in esoteric and occult novels written by non-Masons led him to search out real Masons to find the truth. Graber and Walls noted that popular films referencing Masonry like National Treasure also piqued outsider interest in the organization.

In terms of going beyond the basic level of inquiry, Spooner said that there are three main motivators that encourage people to officially join the organization.

“First, they want an opportunity for fellowship — genuine connections with quality men that share their values in life,” he said. “Even in our current digital world, people still want to be able to sit down and have a conversation with someone they can trust, someone they can relate to.”

Under this category, the idea of Masonry being a close-knit fraternity falls.

“The second one is opportunities to learn and to [experience community] in an environment that is supportive,” he said.

This includes the knowledge acquired through a Mason’s degree progress as well as skills like public speaking and event planning and coordination that arise out of being a leader within the lodge.

“The third is the opportunities to contribute and make a difference — fundamentally just to help, to be useful,” he said.

Spooner said that the technical term used by the Masons for this category is “relieving the suffering of others.” Under it falls the outreach programs of the organization, such as its hospitals and charities.

Together, these three reasons encompass the three core tenets of Freemasonry that go back to its founding: Brotherly Love, Relief and Truth.

Diversity

“Group of Grand Lodge of Masons. No. 2,” photographic print. (Photo: Library of Congress)

During my post-research phase, I discovered that many people view Freemasonry as lacking in diversity. While this may be true of many small Illinoisan towns whose populations are overwhelmingly white, it is not true across the board.

For Hesperia Lodge #411 — located in the metropolis of Chicago, diversity is not a shortcoming.

“We have a pretty eclectic lodge,” Harvey said. “We’re not like a lot of other lodges…There’s a wide variety of people, and the beauty of our lodge is everyone feels comfortable. We have a number of gay members. We have a number of any race you can imagine.”

While many bodies within Freemasonry have traditionally excluded the LGBTQ+ community, the wheels of time have turned, and many lodges around the world now welcome and initiate gay and trans individuals, though the inclusion is not universal across all lodges. The decision to include or exclude people with LGBT+ identities is made by each Grand Lodge, which operate independently from one another. A Grand Lodge may decide to make a decision to include people with LGBTQ+ identities affecting all lodges or may allow each individual lodge within its jurisdiction to make the decision themselves.

Regarding racial diversity, its history in American Freemasonry goes back to the nation’s founding. In fact, the oldest organization founded by African Americans, Prince Hall Freemasonry, dates back to the 18th century.

In 1787, Prince Hall Freemasonry was officially formed. Its namesake, Reverend Prince Hall, was first initiated as a Mason in March 1775 along with 14 other freed men serving in the British Army.

Having been granted the right to begin their own lodge but not to confer degrees, the group founded African Lodge #1 in 1776.

Pledging allegiance to the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, Hall stressed the importance of equality among races and employed Masonic concepts to assist Blacks in achieving economic success in America. He was also an early abolitionist, petitioning for the government of Massachusetts to end slavery and preaching the importance of emancipation.

Following the war, Hall continued his efforts to fight for the right to become first-class citizens through his fight to convert African Lodge #1 into a fully functioning lodge. While African Lodge #1 was an official lodge, the restrictions placed on it during British rule were still in effect.

Initially, Hall’s efforts were turned down by Massachusetts’s Freemasons, despite his favorable reputation within the state’s Masonic community. Not giving up, Hall petitioned the Grand Lodge of England in 1784, and in 1787 and he received confirmation that he was granted the right to his own lodge, according to Middle-class Blacks in a White Society: Prince Hall Freemasonry in America by William A. Muraskin .

Spooner, a former member of a Prince Hall lodge, explained that Prince Hall Masonry created its own Grand Lodges and functioned as a separate unrecognized system alongside traditional Masonic practices until very recently in American history.

The Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Illinois and the “Mainstream” Grand Lodge of Illinois were not mutually recognized until 1998. Meaning, membership from one could not be transferred to the other. Both were considered official Masonic organizations — but only in their own right. The recognition did not exist across the borders between the two.

The Prince Hall Grand Lodge still exists as a sovereign body under the new recognition, but its members are now allowed to transfer to lodges outside of Prince Hall Freemasonry. Under the former system, those members would have to complete a full initiation to join an outside lodge and vice versa.

Per Spooner, the recognition of Prince Hall Freemasonry was the result of societal maturation over social justice issues.

“It’s just a matter of time healing various types of issues,” he said. “And then, people actually coming more together says, ‘Hey, in this day and age — like I said for us 20 years ago — it’s like, come on, we’re brothers because we know we have a common history similar to…any other regular Grand Lodge.’”

To date, 44 out of the nation’s 51 Grand Lodges have recognized their Prince Hall counterparts. More on Prince Hall Freemasonry can be found in the video below:

(Video: Library of Congress)

Religion

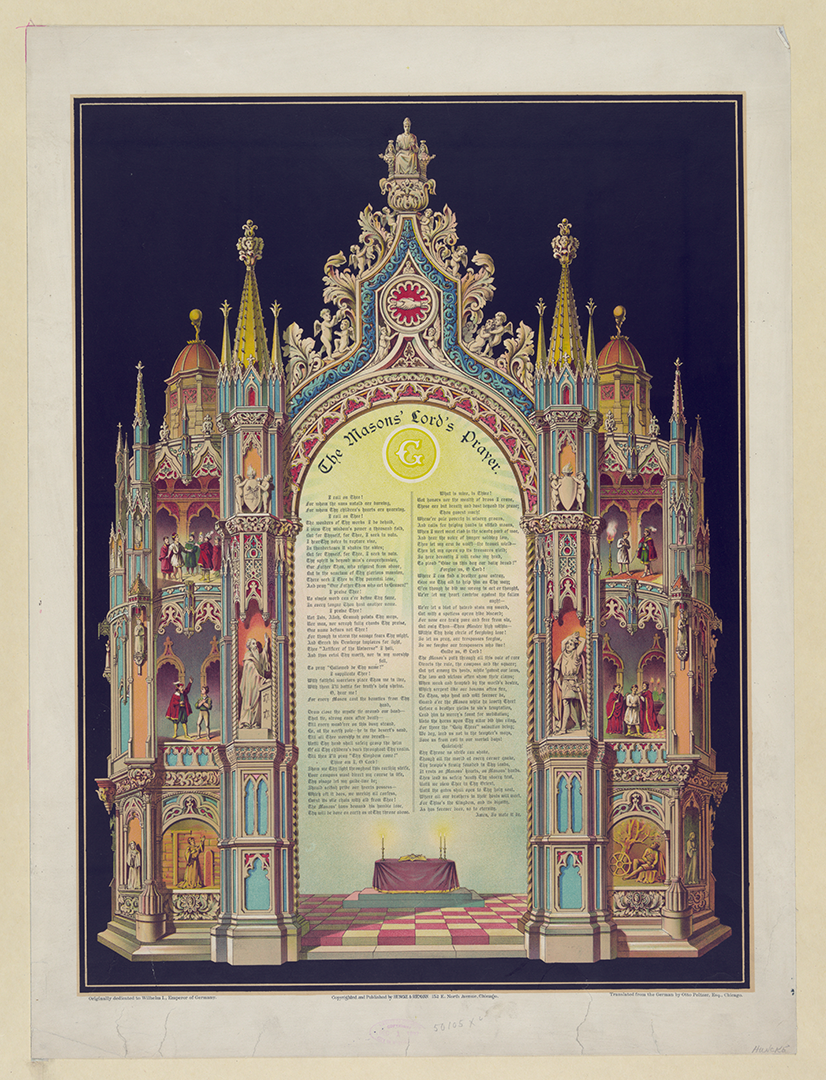

“The Masons’ Lord’s Prayer,” chromolithograph. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Transitioning to the topic of religious diversity, though Freemasons make heavy use of Judeo-Christian themes, anyone is welcome regardless of what religion they belong to, so long as they have faith in a higher being.

“You have to profess your belief in a higher being,” Walls said. “Now, that higher being can be just about anything. In fact, there’s a Scottish Rite degree where it’s ‘Wakan Tanka,’ which is an Indian god.”

The requirement of religion is necessary for the fulfillment of Masonic ceremonial requirements.

“The reason an atheist can’t be [a Mason] is because they don’t believe in God,” Walls said. “So, they can’t swear on a Bible or Quran or anything else.”

Apart from asserting their belief in a higher being, a Mason’s religious beliefs are kept as a private matter.

“Two things that are never spoken about inside the lodge walls — ever — are religion and politics,” Graber said. “They are yours and yours alone. We don’t force it upon you.”

“If you look at the overall society, the two things in society that cause the most problems are religion and politics,” Walls said.

“Amen to that one,” Graber said. “You know, we don’t have debates in here about whether you’re Republican or Democrat…because, I’m sorry, I don’t care what you believe — that’s your business. But, inside here you are a Mason — end of it.”

Though, the degree of this hands-off approach to one’s beliefs varies between lodges. At Springfield Lodge #4, religious devotion and practice apart from what is required of Masonic ceremonies is strictly prohibited. However, at Hesperia Lodge #411, the lodge does play a small role in one’s religious walk.

“We actually do teach within our system…if you are involved in your church, you should become involved like 100 percent,” Harvey said. “Involve yourself even more. Go all the way. We are really here to augment what people are doing along those lines.”

In this role, the lodge acts to motivate — not influence — the religious beliefs of its members under the support of brotherhood.

While Freemasonry does not prohibit any religions from joining, followers of certain religions may be barred by their faith from joining organizations like Freemasonry.

Followers of the Missouri Synod Lutheran denomination, for example, are prohibited from gaining membership in the organization due their interpretation of the gospel under threat of excommunication. It is not Freemasonry which prohibits its followers from joining but rather the denomination itself.

Religions such as Roman Catholicism have bans against their followers becoming Freemasons, but these do not result in excommunication. Despite the church’s opposition in such cases, adherents are still able to become Masons.

To reiterate one final time, though belief in a higher being is required of and included in Masonic traditions, religion itself falls outside the reach of Masonry.

“Masonry is not a religion,” Graber said. “We allow you to practice whatever you want.”

Conclusion

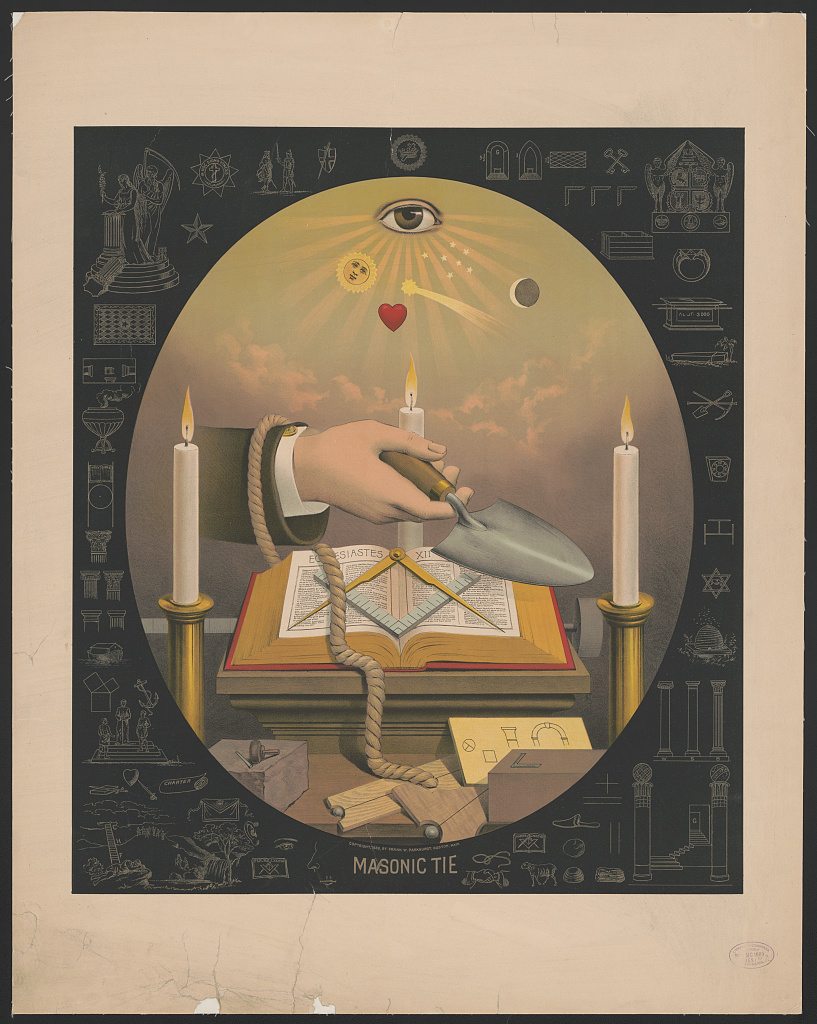

“Masonic Tie,” chromolithograph. (Photo: Library of Congress)

I conclude this article with the hope that those reading this article walk away with a greater understanding of Freemasonry that goes beyond its pop-culture representations as a kooky world order.

Freemasonry is a community-centered organization deeply rooted in history that has grown amid roadblocks of the past to be inclusive and thriving. Its tenets of brotherly love, truth and relief aim to empower and support not just Masons but also those whose lives are able to be touched by Masons.

“Masonry seeks to unite people,” Harvey said. “It seeks to unite humanity as one secret band of brothers.”

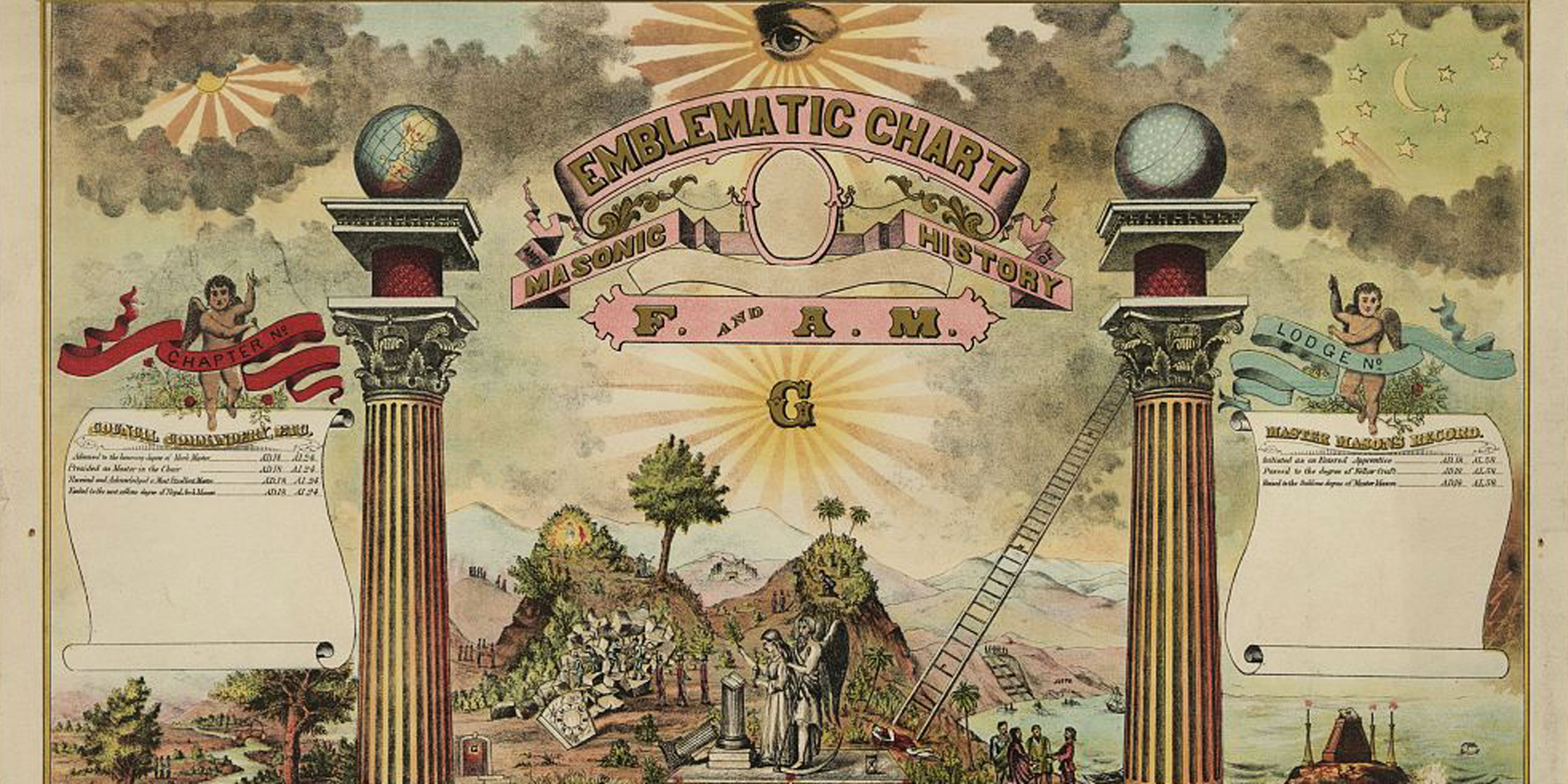

Header image: “Emblematic chart and Masonic history of F[ree] and A[ccepted] M[asons],”

chromolithograph. Library of Congress.

NO COMMENT