The COVID-19 pandemic has left millions without work. So what happens to bills?

Waves of business closures in the past several weeks due to the novel coronavirus pushed a record 6.6 million Americans to file for unemployment in the month of March.

The surge of furloughs, a backlog of unemployment claims and weeks of lost paychecks peaked just days before April 1: rent day.

Facing the likelihood that thousands of people in Illinois and the city of Chicago would be unable to pay rent for the month of April, Governor J.B. Pritzker issued a ban on evictions until April 30.

Additionally, on March 27, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced a rent assistance program that will grant 2,000 individuals a one-time $1,000 check –– half of which will be distributed by a lottery system, the other half by community nonprofits in the city (deadline to apply April 1). And for renters specifically, there is an emergency rent-assistance program that residents can apply to that will make payments to landlords 7 to10 days from the time of application approval.

However, system overload, ineligibility and bad timing moved many of the city’s residents to organize with their neighbors, tenant unions and nonprofits to call for a rent strike.

“A lot of people just lost their jobs two weeks ago, me included, and some people just won’t be able to pay rent,” said Brian Bennett, an organizer with Chicago Democractic Socialists of America. Chicago DSA is one of several groups in a coalition demanding a rent freeze for the duration of COVID-19 restrictions.

Bennett said that a distinction should be made between a more typical rent strike, in which tenants in a building or management group refuse to pay rent until demands are met, usually regarding unsafe building conditions, high rents or tenancy requirements.

“There’s a big difference between people just not being able to pay rent and more of an explicit political project that you might call a rent strike,” Bennett said. “In fact, it’s kind of like the difference between, you know, people going on strike at work versus people, let’s say, getting injured and not being able to go into work.”

In a publicly streamed virtual town hall call hosted by Tenants United on Wednesday, tenants from areas across Chicago vocalized their experiences of job loss and need for further action by the city and state to help them avoid debt or potential homelessness in the future.

“I’m a server at a busy downtown restaurant. I showed up to work on Sunday, [March] 15 and found out that the 16th would be our last day. I basically had 24 hours’ notice,” said one participant. Participants in the call were using Zoom usernames, which made it difficult to verify the names of those who spoke.

“I’ve been going through the process of applying for unemployment and SNAP benefits since I was furloughed, but the hotline is very backed up. It’ll basically be another month before I see any income, and I’ve already lost two weeks of work.”

A number of participants echoed similar concerns. Some also mentioned supporting children who are no longer in school or taking care of ill family members as well. Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez (25th) and Ald. Rossanna Rodriguez-Sanchez (33rd) were also present on the call in support of the tenant movements.

An organizer from Tenants United, which is based in Hyde Park, said that this crisis and rent strike are a climax of public tensions related to housing that have existed since the 2008 recession. This crisis, they said, has intensified the problem.

Tenants United is targeting a specific handful of landlords, including Mac Properties, mostly on the South Side, and Pangea, which has properties across the city. The organizer said that the response from some landlords has been to encourage renters to enter rent agreements with their individual landlords.

Peter Cassel, director of community development at Mac Properties, said that they’ve encouraged residents to reach out to them directly to discuss plans for rent payment.

“What we have done was to invite our residents to contact if they’re not able to pay their rent. To be able to contact us. And then we are working out payment plans, relocations and/or lease terminations, depending on whats best for the residents and with those who can demonstrate immediate financial hardship.”

He also said that of the roughly 5,000 apartments under the company in Hyde Park, they’ve had hundreds reach out to negotiate rent arrangements after losing their income.

“We know that it’s real, we know that many of our residents appreciate both the rights and obligations of residential leasing agreements,” Cassel said. “I think we’re working through this with many of them, you know, we’re getting to a variety of solutions, all of which are particular to the individuals that are in their particular circumstance.”

However, Cassel also voiced some criticism of activists blurring the distinction between those who cannot pay rent due to loss of income and those who perhaps still have income but are vocal about a rent strike.

“I’ll make a distinction between our tenants who are having a hard time paying rent this month and a small but vocal group calling for a rent strike,” he said. “We have a number of our residents who are service workers, or for example work in an office that is just completely closed and they’ve been laid off. We understand that their position as someone who has just lost all their source of income is in a very different position than someone who perhaps works for a well-funded anchor institution with an endowment, or a company that has continued to pay its workers.”

14 East also reached out to Pangea Real Estate by phone and email. At the time of publishing of this article, Pangea had not returned emails sent through their online submission form and a representative they could not give out individual property managers’ information for contact. 14 East also reached out via Twitter and Facebook.

For some, individual landlord agreements are a viable option. One participant in the virtual town hall on Wednesday said that she’s been “organizing the tenants in my building and just received an offer from [my landlord] to take off half of my rent for the next two months.”

However, some landlords have been offering to break leases and push for “self evictions” in these agreements if they can’t pay rent this month, said the organizer at Tenants United.

There is an added caveat of pure scale in this dilemma as well, said Professor Euan Hague. He is the chair of the School of Public Policy at DePaul University and studies housing policy and movements. With giant property ownership/management companies, Hague said the ability to waive a month’s rent could be different than that of small-time landlords.

“I think if you had landlords waiving rent for a month, which obviously would be very helpful for many people. But not every landlord is somebody who owns 100 properties, right? Some people might just own a couple of buildings or something like that,” Hague said. “So I think that the issue of scale is another important one.”

Hague said it’s also important to remember that rent payments are situated in a much larger financial network that is being impacted by the COVID-19 crisis, which requires more levels of action by institutions.

“It’s all part of a big system, right? Because a landlord is often paying a mortgage,” he said. “And so, they’re using the rent to pay the mortgage, and the bank is demanding the mortgage. And if the bank doesn’t have it, you know, all these things are connected.”

It’s all further complicated by the fact that there is little precedent for a rent strike of this scale in most of modern history. The closest examples are mostly in the rent strikes of the World War I era in Europe.

One, in particular, took place in Glasgow in 1915. Demand for wartime workers in the industrial Glasgow area saw sharp increases and thus, so did the demand for housing and the prices that landlords were charging.

A group of women, the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association, organized a rent strike in May of that year, successfully unifying 25,000 tenants to demand lower rents and better conditions. The government responded with a rent freeze that held rents at 1914 levels until improvements to the properties were made and the wartime demand stabilized.

Yet even this example does not meet the scale of the mounting housing crisis in the United States. Without action from state and local governments and, eventually, the federal government, homelessness and foreclosure could skyrocket.

“Unless the government steps in to mitigate…to give rent support to people… down the line in the next few years you’re going to see high unemployment rates, high rates of homelessness,” Hague said. “It needs collective effort.”

Turning towards solutions, European nations ahead of the U.S’s virus curve have been passing massive stimulus packages and agreeing to pay high percentages of workers’ normal wages to keep things afloat.

“Whereas in other countries they’re saying, ‘Okay, we’re not going to send you a check,’” Hague said. “The government’s going to step in to cover 80 percent of your wages. So, as a result, that’s a very different way of maintaining the economy.”

As this crisis continues to unfold, the current U.S. relief package could prove unable to support an extended period of unemployment and, therefore, an ability to pay rent.

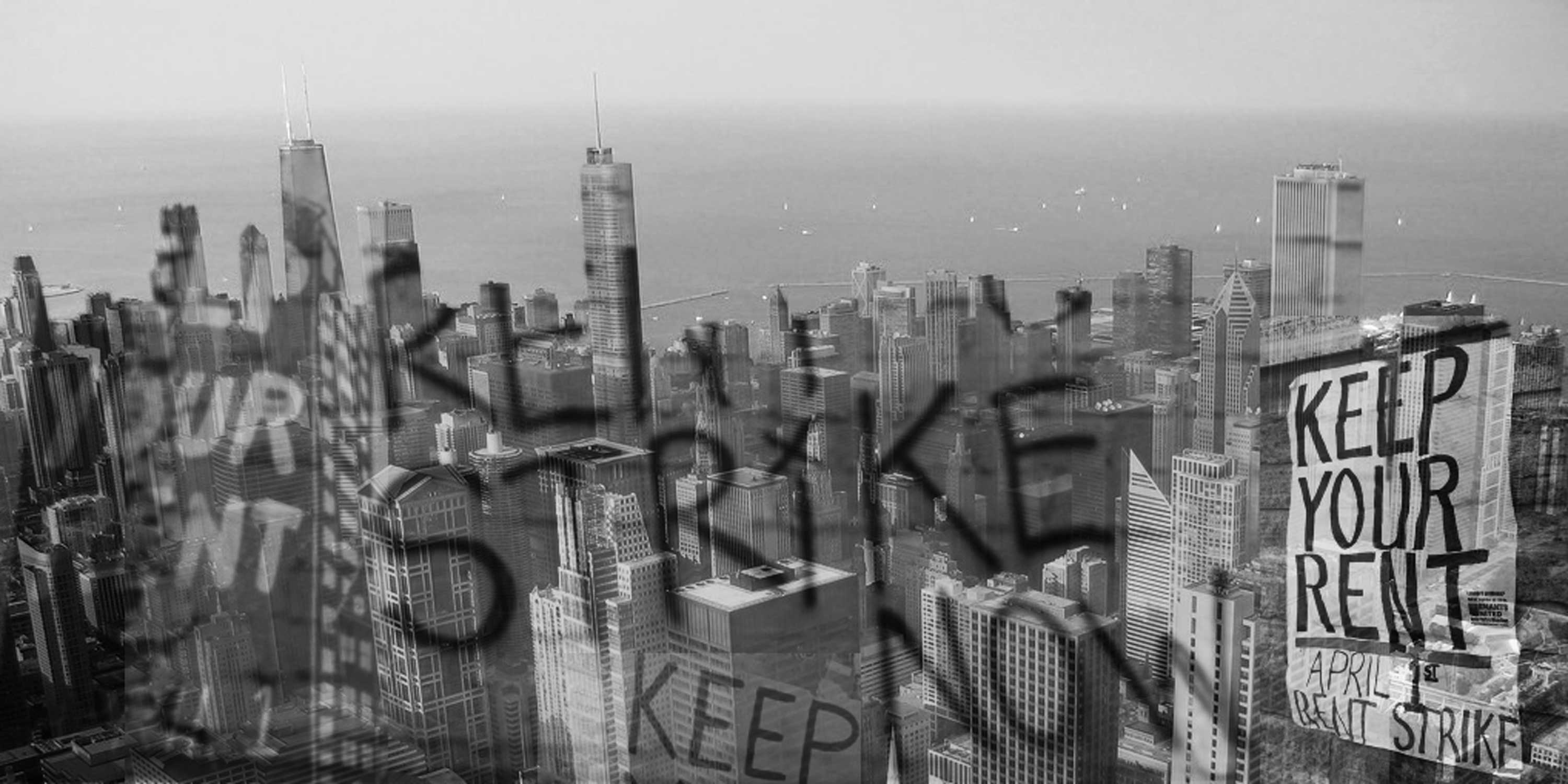

Header image by Natalie Wade, 14 East

NO COMMENT