A local film photographer turns home into film development studio to make ends meet during stay-at-home order

After Governor J.B. Pritzker’s stay-at-home order announcement on March 20, Anna Malek didn’t know how she was going to make ends meet.

A film photographer of almost nine years, and employee of Central Camera for two years, Malek works in sales.

She said upon the announcement she felt uncertain and just days later was told that she would not have a job for the duration of the stay-at-home order.

“I was just like, ‘Oh, great, I’m not going to have a job,’” said Malek. “I wasn’t sure how unemployment was going to work so I said, ‘Let me start developing film.’”

Since beginning her at-home development studio at the end of March, Malek has made over $300 in profit and has over 20 regular customers.

For anyone who still may not be familiar with what analog photography is, Malek’s explanation described a process of combining both art and science.

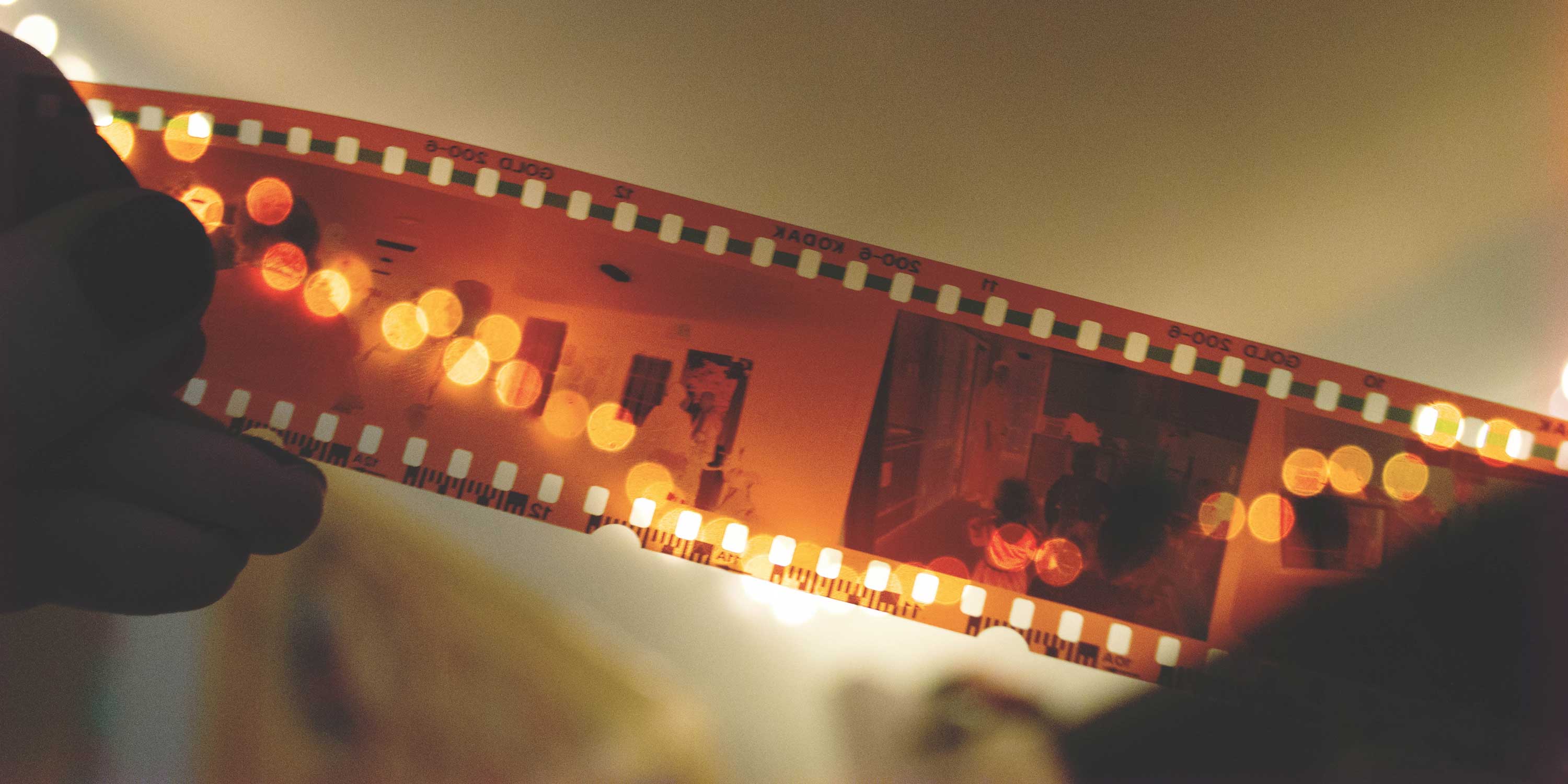

“Negatives are blueprints of your pictures,” she said.

When using an analog camera, the image is taken by light being captured on a roll of film. The image is hidden until specific chemicals are poured onto the film, which in turn allow the images to appear. The images can then be scanned into a computer to make digital copies, but they always start as rolls of film — tangible blueprints of images that are coaxed to the surface by a chemical concoction.

Malek’s at-home services have caught the attention of the Chicago analog community, creating loyal customers out of photographers who needed their film developed when other businesses are closed. One of these customers is Tom Simmermaker.

Simmermaker works for a local tech company in Fulton Market, but spends as much time as possible outside of work with his Minolta XG-1, an old film camera he’s been using for five years.

As non-essential businesses closed due to the stay-at-home order, Simmermaker started looking for other ways to have his film developed. So, he was relieved to receive a message from Malek on Instagram saying that she was developing film at home.

In order to exchange the film, customers can drop it off on Malek’s doorstep (although she does offer to pick up for a fee of five dollars). Post-development, it works the same way but Malek also offers to mail the photographs to customers.

“I think it’s so badass that she’s doing this now,” said Simmermaker. “It’s a hard time to be … a successful and productive creative. I’m inspired by it, that she took this initiative and I’m so thankful she’s doing it.”

While Malek started with only a few customers, the rapid rise in the number of her customers — going from three to 20 in a matter of days — connects back to one of her regulars, Ethan Chaparro.

Chaparro belongs to a group of local film photographers, many of whom needed places to have their film developed during this pandemic. This group — the Chicago Analog League — put Malek’s contact information on a section of their website devoted to local photographers who offer development services from home.

Rogelio Vega, one of the two League founders, said Malek’s work is truly important.

“People need to record their life, and they need to be able to see it [their photos] and hold it in their hands, like it’s okay, this is happening,” said Vega. “A lot of people are scared to develop their own film, they want to get it back so they can say, I have this now. This is mine. Whatever happens, I have this. It’s awesome that she’s doing this.”

Another customer, Khoa Dao, said Malek’s business is key in aiding photographers in their recording of history.

“Who are essential workers? Technically, photography isn’t essential, but we should have records of what’s happening,” said Dao. “She is providing relief to artists who are recording this pivotal moment.”

Throughout every conversation had with Malek’s customers and others alike, the photographers all harped on the single same aspect of film photography: its tangibility.

It’s a feature that digital photography, no matter how dimensional, can’t offer.

Gerri Fernandez, also a founder of the Chicago Analog League, said that for her, the tangibility of taking a photo and going through the process of developing it from start to finish is one of the biggest draws to film photography.

“For analog, in particular, it forces you to slow down and think about what you’re doing,” said Fernandez. “You make something with your hands; you’re with it through the whole process. I care more about the process than the end result. I feel like it helps you sort of just slow down and think about what you’re doing.”

Although the process of developing their own film is very important to Vega and Fernandez, for photographers like Simmermaker, Dao and Caparro who can’t develop their own, Malek has proven herself to be the next best thing.

“Working one on one with an artist and photographer during this time felt extra fun and rejuvenating,” said Simmermaker. “[I] felt like we were supporting each other’s creative work, and she did such an amazing job, I love these pics.”

Although Malek comes from a family of small business owners — her mother owns a goat cheese shop in her hometown in New Hampshire — she doesn’t intend to continue her at-home business once Central Camera reopens because she doesn’t want to take business away from the store. However, she said she hopes other creatives will take this opportunity to open their own businesses.

“If you have the skills, do it. I definitely had a sense of, ‘Should I do this?’ I felt a sense of, ‘Is this going against my job?’ But then I was like, ‘Wait a minute, hey, I’m only doing this until the store opens back up,’” said Malek. “There is no shame in charging people for your craft and your art. You’re putting time into this.”

Have film you want developed? Message Anna on Instagram @anashootsfilm or email her at amalek310@gmail.com.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story said Malek develops analog film in Central Camera’s darkroom. She does not, she works in sales at the store. A change has been made to reflect this.

NO COMMENT