“Americans are the best entertained and quite likely the least well-informed people in the Western world.” -Neil Postman

If you’re anything like me, you have undoubtedly spent a lot of time online throughout the quarantine period. When you find yourself online for multiple hours a day, you start to notice trends about the content you consume.

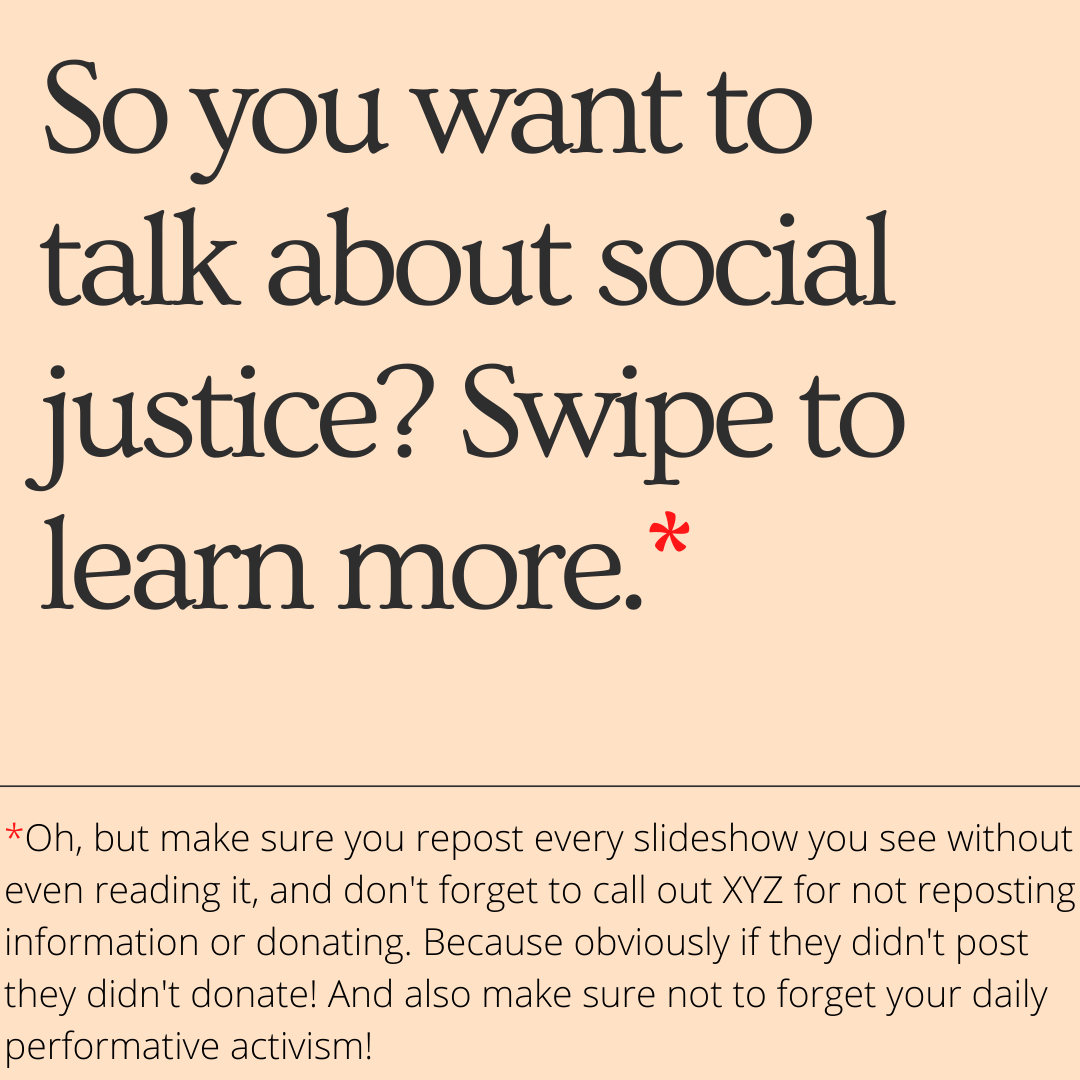

While anyone can point out a trend when exposed to it enough, it is imperative that we assess these trends and what they have to say about us as consumers. In doing so we can become more well-informed and knowledgeable people. After all –– what good is being the number one sharer of information and resources on Instagram if the content you share is incorrect or mistaken? Alternatively, what good is creating tons of captivating graphics, if you aren’t actually digesting the material or are sourcing incorrect information?

In 2017, Instagram released an update allowing for one post to contain multiple pictures and videos. This is notable because the app, released in 2010, was unlike Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook, which at that time already allowed for multiple pictures to be included in single posts. This feature was, at that point, often used for stringing together pictures from a night out with friends, random moments throughout the week or sharing some funny memes. Instagram’s carousel feature has been a largely noneducational tool as Instagram is an app primarily focused on entertainment and photo sharing. But what isn’t entertainment? And what happens when educational content is branded as such?

It is very easy to passively consume and reshare content that one might think is helping to keep themselves informed. It is just as easy to do this without any additional research on the subject matter in the future.

Infographics can be fun. Designers put in an enormous amount of work to make them captivating and entertaining. Much thought is put into the colors used, poppy and bright or saturated pastels, fonts implemented and the graphics spread across these digital carousels. But Instagram is an app of vanity, consumerism and self-absorption. This makes for an issue when educational information is the “product” being marketed. We are living in a time when caring about social justice is just as hot of a commodity online as posting a nice outfit, or sharing one’s extravagant vacation photos.

Cultural and media critic Neil Postman wondered about the harmful effects of, in his words, everything being entertaining, in his 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves To Death. In this work of American cultural and media criticism, Postman argued that America’s transition away from printed media has changed the ways in which we deploy knowledge. Postman contended that our assimilation to the ideas foundational to the telegraph and photograph, which led to television culture, has negatively affected the ways in which we consume information and share knowledge.

Postman explained that the television served as the most “potent expression” of the telegraph’s and photograph’s biases regarding knowledge: instancy and imagery.

Living under capitalism provides for anything and everything to be commodified: this time, activism is on the market.

He believed that the television did this to a “dangerous perfection,” concluding by stating that “the problem is not that all television presents us with entertaining subject matter but that all subject matter is presented as entertaining.”

To be sure, I am not saying that Instagram is ruining activism, or that sharing resources and information online is unwarranted because that is simply not true. Culture writer Mary Retta argues that social media can be a tool for those without a foothold in traditional media outlets.

“The right-leaning scope of traditional media practically necessitates social media journalism, a space where activists and leftist voices can be given a platform to share their ideas,” she wrote. Retta concluded her piece by saying that Instagram journalism gives agency to those who have not had opportunities to “have control over our own narratives.”

This is why it is increasingly important that we are aware of what we consume on Instagram. If social media is to be used as a tool for those lacking mainstream reach and appeal, the posts we see across our feeds should be examined for their civic integrity. In an essay for Bustle, Diyora Shadijanova questioned whether Instagram activism is performative or helpful. Initially, Shadijanova echoed the aspect of the accessibility social media provided for activists which is unparalleled in our mainstream media, but she also points out opportunism by way of “some brands and influencers” using this politically charged moment in order to “give the illusion of making change.”

Graphic by Yusra Shah

This connects to one of the primary issues with Instagram activism, namely, persons or groups thinking that it is en vogue to preach about social justice, while not taking meaningful steps in their own lives, or in the ways in which they move throughout the world. Living under capitalism provides for anything and everything to be commodified: this time, activism is on the market. Brands and personalities are quick to jump on trends when it’s marketable.

What good is a graphic on an account with no social media traffic? asked Shadijanova. “The value lies in the ability of infographics to reach a huge audience.”

These graphics need to grab the eye. The graphics need to be something people feel proud of showcasing and sharing with their friends. This can be a problem when sharing information about sensitive topics. A designer has to walk a thin line between accurately showing the pervasiveness of anti-Blackness, misogyny, policing, plus more, and making an aesthetically pleasing design that people feel is cool enough to share around.

Some are using this moment in society to posture themselves as radical or well-informed with the goal of appearing more socially and culturally aware than others.

Shadijanova understands that most people are genuinely trying to be helpful by sharing educational resources. This situation is nuanced, however, because while it is possible someone truly believes they are helping to spread a message — what often happens is complacency post-posting. It is very easy to passively consume and reshare content that one might think is helping to keep themselves informed. It is just as easy to do this without any additional research on the subject matter in the future.

The instantaneous nature of social media is both a blessing and a curse. We can quickly divulge important information, like what was seen at the height of the Minneapolis uprisings, sparked by the killing of George Floyd. Apps like Instagram are accessible for those who might not have the access to major media outlets, but still want to get their message heard by others.

Social media journalism and online activism generally can be democratizing in that it levels the media playing field for those without immense networked connections. Unfortunately, social media is not without flaws.

Issues of self-glorification and passive consumption are still prevalent upon the introduction of using our feeds for journalism and resource sharing. Some are using this moment in society to posture themselves as radical or well-informed with the goal of appearing more socially and culturally aware than others. Some are well-meaning in that they want to become more well-rounded and knowledgeable on the issues we are met with. Either way, social media should be looked at as a tool for building a more informed worldview, rather than the primary way in which we learn about the gnarled society we find ourselves in.

Header image by Yusra Shah

NO COMMENT