Click here to read the story in Spanish.

For my Winter Quarter classes this past academic year, I switched Quantitative Reasoning and Technological Literacy II with Environmental Philosophy.

It really comes back to the Environmental Philosophy class. In this course, we first looked at the historical sources of societies’ incapacity to care about the environment through philosophical books and texts such as Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer and Georges Bataille’s Theory of Religion. Taking into consideration that Nature, the Earth and the ideas about ourselves are inevitably historically driven, how do we begin to see Nature in a different way or act towards Nature differently? In the beginning half of class, we became familiar with reading on a feminist framework, thinking about Nature, using the “Land Ethic,” delving into Indigenous thinking towards Nature and the environment along with other texts. I am now seeing the curriculum from this course play out in the dialogue and writings of the Black community and recent #BlackLivesMatter uprisings, from abolitionists and from climate activists such as Cathy Park Hong, Adrienne Maree Brown, Ibram X. Kendi, and Naomi Klein.

Most of them are all asking you similar things.

To imagine.

To begin the path of solely thinking.

To start over.

To reject individualism and invite collectivism into your life.

To make sure your anti-racism plans are long term.

To implement accountability.

Now, what does any of this have to do with identity or who am I as a person?

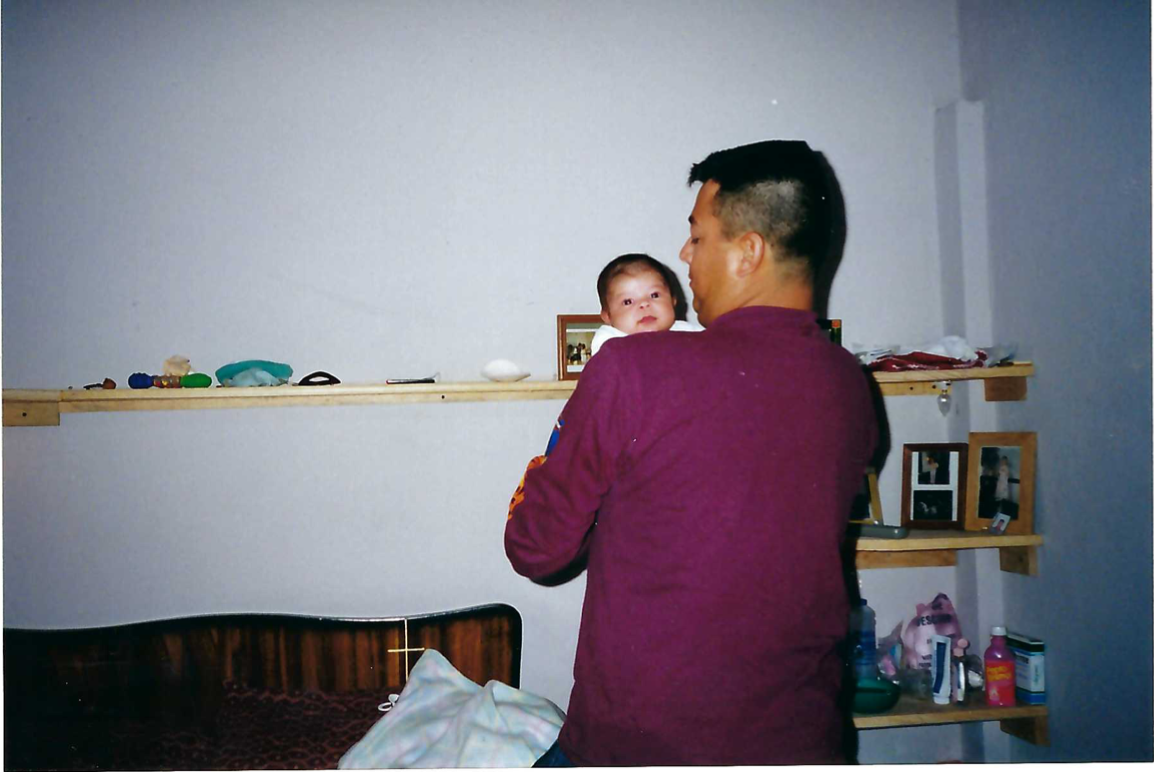

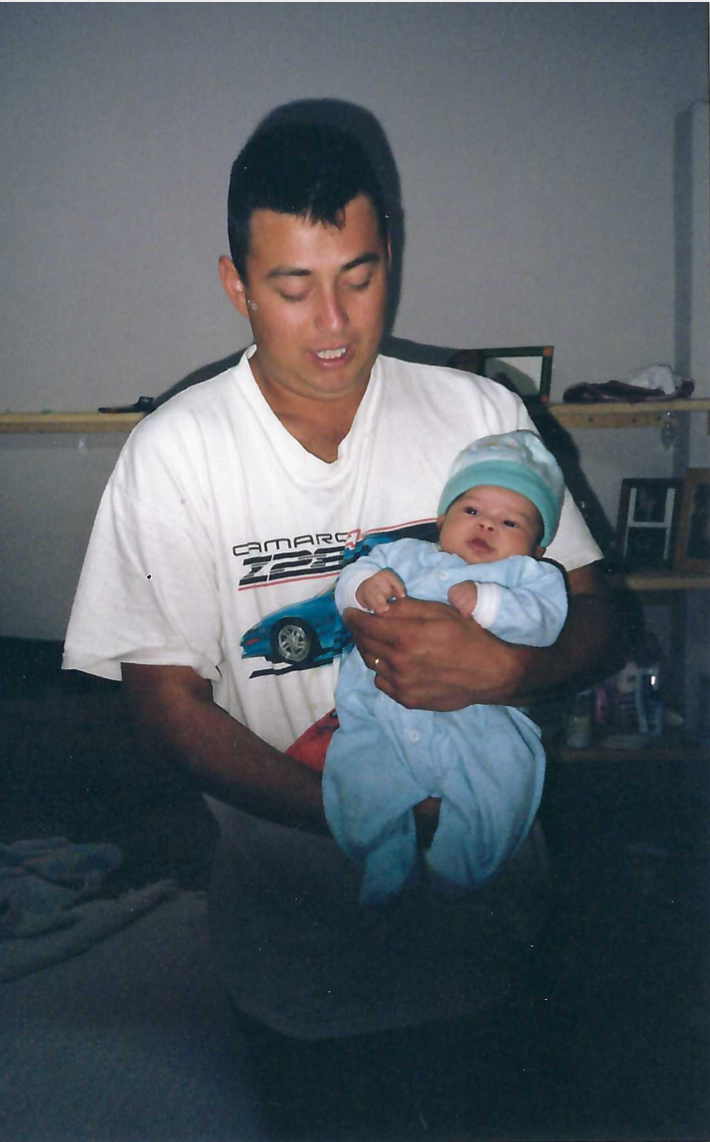

I felt helpless in the first half of the class, but later on I began to have these memories of photographs of myself as an infant to a small child on the farm my dad’s family tended in Aguascalientes, Mexico.

They were incredibly intense feelings. I would start out crying but not from sadness. It felt similar to when you miss something or someone, but I was confused because I was only missing memories of photographs and not the actual memories that coincided with them. The first time it happened was when reading Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, about his life on a farm in Wisconsin. With his witty and poetic tone, he taught us how we can appreciate nature because it serves as cultural education but also because it is beautiful.

These memories of the photographs felt like they served a purpose towards something I did not understand quite yet – until we read an excerpt from Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. In this text, Kimmerer breaks down the grammar of animacy in relation to her learning the Indigenous language of Potawatomi. Animacy is implemented into languages to describe how there is life within itself. Kimmerer says, “Water, land, and even a day, the language, a mirror for seeing the animacy of the world, the life that pulses through all things.” In this chapter, she discusses how learning the language of Potawatomi and understanding the grammar of animacy, as a person of Indigenous background, feels not like something new but something that has always been there. She refers to it more as remembering.

That was when I felt that something settled in me.

There are some things that exist beyond matter. For me, it is this feeling that I have with these photographs of memories as a small child on my father’s family farm.

Everyone has told me bits and pieces of this story in the photographs.

In 1999, my parents were married in Mexico while my mom was 7 months pregnant with me.

My mother was already an American citizen, but my parents met while my dad worked in the United States for support to the family farm. Once they were married, my mother worked to get his paperwork together so he could come to the United States and we could all be together.

Overall, they spent 18 months on all the paperwork and issues with immigration. My mom traveled with me while she was pregnant and would visit my dad after I was born throughout all this time.

I spent my time in my mother’s womb on this farm.

I spent my first month of life on this farm.

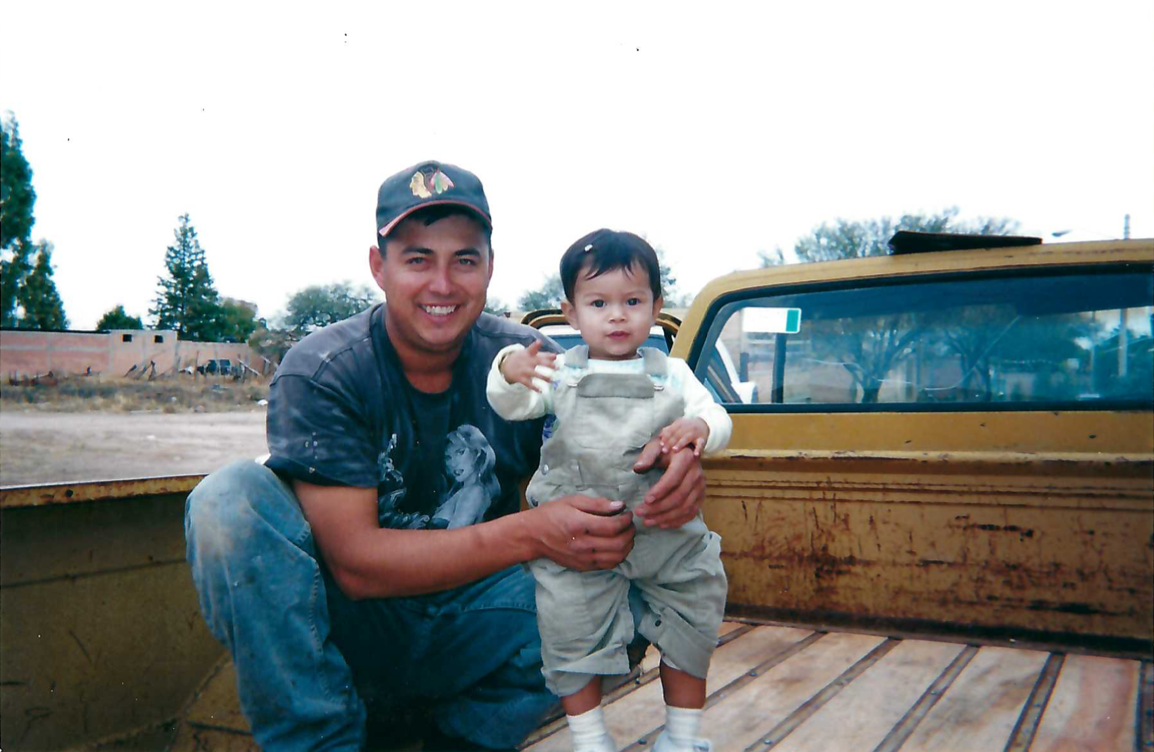

I spent time with my dad on this farm as a child.

As I am writing this, I am crying.

The lengths my mom went so that we could be a family reflect highly on the love she has for my father and me. That is worth many tears.

Yet, I did not know this story in full until I chose to write this. Only the pictures.

It is as though I can see the memories in the photographs in my mind like the memories of my most recent birthday festivities. Yet, I have this relationship with Nature, specifically a family farm, and those memories have become a part of who I am.

These memories guide my decisions and my implications in the world. In the preface of Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer vividly describes the smelling of sweetgrass with connection to Mother Earth. You “breathe it in and you start to remember things you didn’t know you’d forgotten.”

These memories and the feelings I have with where I started my life are everything about who I am.

I am aware that I overused the verb to feel. My argument, whether you believe it or not, comes from pathos. In colonized cultures, pathos has been denoted solely to emotion. When in fact, arguing from pathos means receiving the world’s intelligences and how the world affects me.

For me, Nature and my Mexican identity are deeply intertwined.

They do not feel separate from one another but in fact help me to understand that I am not separate from anything. I am not separate from what is happening to Black and Indigenous people all across the United States. I could never know what it means to be Black or Indigenous but that does not mean we are not connected by something larger. That does not mean my vision for the world doesn’t include rebuilding and reimagining our society out of frameworks that honor Nature and empathy. You listen. Though I am Mexican and my parents are both immigrants, we have never been interrogated about our citizenship status. To me that implies the privilege I carry and my responsibility to stand up and give support for other immigrants, DACA students, refugees, asylum seekers, every and anybody.

We must think of everyone and everything to be fundamentally connected. We at a base level are all a part of one larger thing. This thing I cannot tell you what it is because I can only imagine what it will be. Therefore, in the meantime, we must connect and follow that everything has to do with everything. Our past is moving behind us and the future stretches.

Header image courtesy of Belinda Andrade

NO COMMENT