El vaquero came before the cowboy. When the Spanish claimed ownership of North American territory in the early 1500s, el vaquero was a Native laborer who was taught the cattle-handling ways of Spanish customs and culture — that is, at least according to the Library of Congress. I question whether the Natives consented, and, if they did, I have to wonder what methods of intimidation the settlers used to force them into labor. I wonder what happened to those who resisted, refusing to betray their beliefs in pursuit of land ownership and I know that those erasure methods are still used by governing oppressors today.

During the early 1800s, English-speaking colonists who had come to the United States began to take on the ways of dressing and herding of the vaquero. Thus, three hundred years after the Spanish created the role of el vaquero, the Anglos took it and created the white American image of the cowboy. It can be said, then, that the modern characterization of the “cowboy” is rooted in a history of North American conquest and appropriation. It is nonetheless one that is very dear to my heart.

My stepfather was raised on a ranch in Mexico; he grew up a “real” cowboy. In addition to the horses and livestock, any picture you find from his youth includes cowboy hats, vests, bolo ties, boots — the “real” cowboy accessories. It’s no wonder, then, that his favorite music is country music.

Mexican corridos, a popular style of folk song, feature outlaw narratives identical to those in songs by Marty Robbins or Townes Van Zandt. Linda Ronstadt, an American singer who got her start in country and folk rock scenes, later paid homage to her Mexican ancestry by recording two Spanish-language albums of mariachi rancheras. And yet, country music scenes are notoriously, historically white. Country music, a withstanding stereotype of whiteness, is so deeply indebted to, among others, Mexican culture.

There are writers far more skilled and well-read than me who can explain the development and popularity of country music in America. I will say that when you look at a genre so rooted in Black and Mexican tradition and then look at the artists who have dominated its charts over the last century, it does not seem like non-white people are too kindly invited.

Why, then, was my Mexican-American childhood soundtracked by the music of Tim McGraw, Rascal Flatts and Faith Hill (i.e. not “real” cowboys or outlaws) as much as it was Paulina Rubio, Vicente Fernandez and Rogelio Martínez? If you were to ask for my theory, I’d say that country was the musical compromise for so many of my family members to both hold on to their ranchero ways and assimilate into a country that relies on immigrants for labor — even though el vaquero did indeed come before the cowboy. This unsettles me because I love country music and the beautiful songwriting that has come from it.

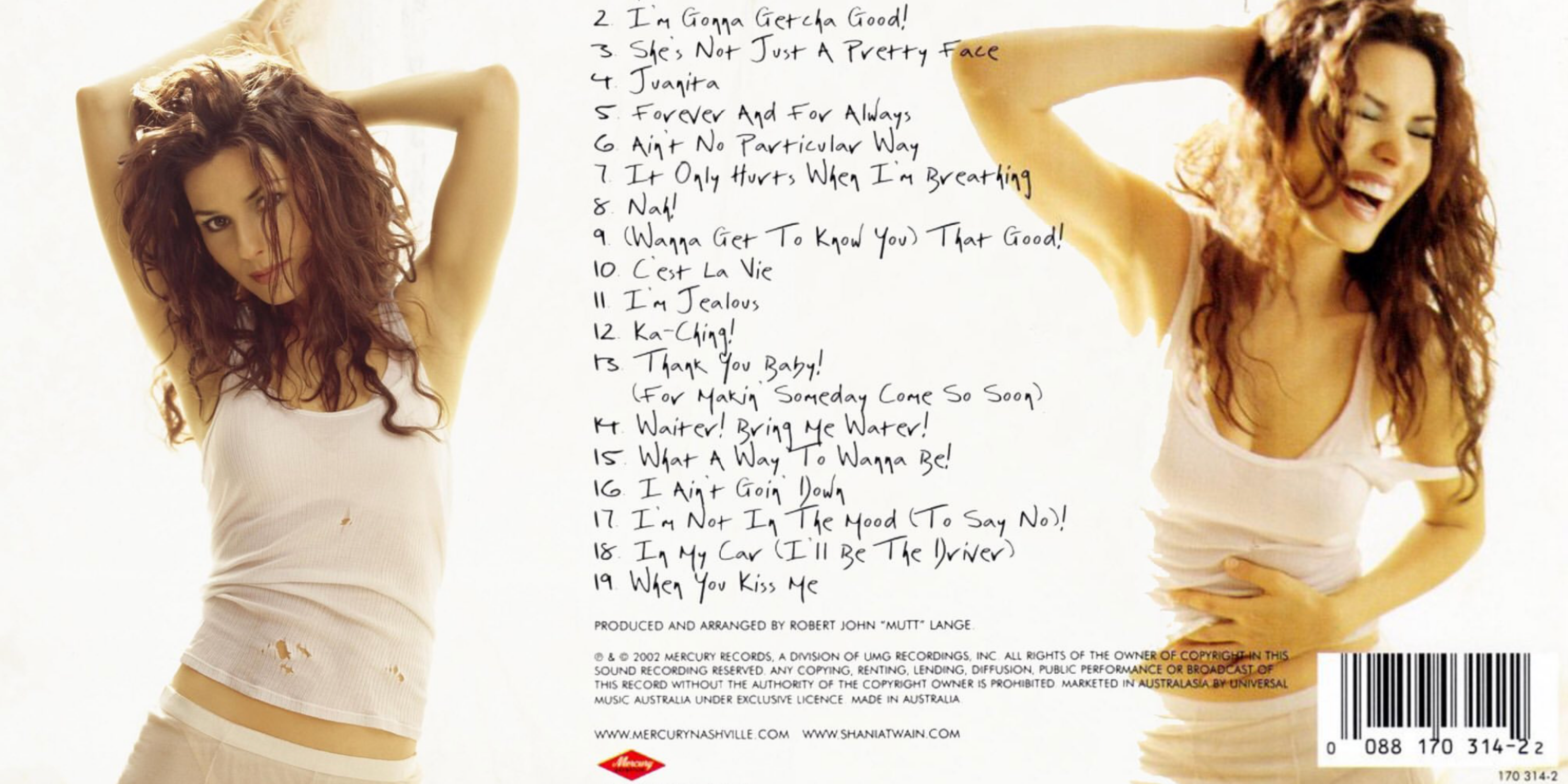

As a kid, country music was always playing in the car. The CD we rented from the public library most often was Shania Twain’s Greatest Hits, released in November of 2004. It is an album of the catchiest country-pop songs I have ever known, each as polished as they are loose and fun. They are devoted to the disciplines and indulgences of love, and it taught those things to a kid who felt welcome in her songs. It taught those things to the immigrant parents who didn’t speak the English language but found solace in its music in a contradictory land they were told to call their new “country.”What’s most striking about the songs on Twain’s Greatest Hits album is how much they are willing to trade country tropes for great pop songwriting. “Forever and Always (Pop Red Edit)” is the first song on the album, and its warm synths remind me less of a twangy folk number and more of Allen Toussaint’s “Southern Nights.” Ironically enough, Glen Campbell canonically covered “Southern Nights” in the country tradition and hit the number one spot of 1977’s country Billboard charts with it. “Forever and Always” is a song about hope, reassurance and mornings, and if you’re not willing to allow sappy heartfelt lyrics past you, I will gently say that this is not the album for you.

It’s worth noting that all of the songs on this record were written by Twain and her then-husband, Robert John “Mutt” Lange, besides one, which was written only by Lange. The sentimental language of these songs, then, is not a gimmick; it is a testament to a real bond and partnership in both music and life.

Perhaps it is thanks to this, and to my newlywed mother and stepfather who soundtracked themselves with country devotionals, that I have a real soft spot for the pureness of love songs. I am most obsessed with the songs that are too genuinely sweet to be true, and yet they persist, all the while moving me to tears. Of the ones I know, “You’re Still the One” by Shania Twain is a personal favorite (“Always Be My Baby” by Mariah Carey and “By Your Side” by Sade are up there, as well).

“You’re Still The One” is another song of reassurance, the kind that a long-term relationship sometimes needs to be spoken when doubt clouds. But it is less about promise and more about the now — about what has been endured, good and bad, to get here and the love that it has only strengthened. As the slide guitar is first quietly heard and the backing harmonies of the chorus hit, the song functions as a beacon, an embrace. It has to be my favorite Shania Twain song.

Conversely, Twain can record a hell of a banger. “I’m Gonna Getcha Good!” is accompanied by crisp electric guitars and undeniable rhythmic claps. “Whose Bed Have Your Boots Been Under?” lilts with upbeat drums and piano, and though its lyrics ask about infidelity, the catchiness of these melodies gives it a confidence that only pop music can. “Man! I Feel Like A Woman!” smoothly layers slide guitar and electric violin over its pop elements to create an anthemic song with so much spirit and sway. One can’t help but smile.

Listening to these melodies now brings me to the backseat of my mom’s old sedan, parking outside a supermarket in the rain or turning off the expressway to get to a birthday party where vaqueros are dancing to mariachi music that booms out of giant speakers. It makes me think of going with my stepdad to work, him walking around on stilts, installing drywall on empty houses as I ate sandwiches by the dirty, staticky radio playing country hits. The songs are barely comparable to corridos in sound, and yet, they made him feel at home.

Over the course of its hour and 17 minutes, Twain’s Greatest Hits drags around the last third or so for me. Maybe it has nothing to do with the songs themselves; maybe it’s because the first few tracks of an album you love tend to hit with the most magic. It could be that the sheer positivity of these last songs becomes too saccharine to my adult ears, knowing that an abundance of good years have been humbled by financial worry, illness, court cases, bum lawyers, griefs, detainments and separations. Against all odds, this does not degrade the reassuring power of a song like “You’re Still the One.”

Twain (who is Canadian, I recently learned) said in a 2018 interview that had she been able to vote in the U.S. presidential election of 2016, she would’ve voted for Donald Trump because “he seemed honest.” She later apologized for these comments, saying that she does not support discrimination of any kind, but I have to wonder what possible pressures of political correctness pushed her to apologize. I think about how different these pressures are from those of an immigrant looking to assimilate, not out of public shame but out of what feels like survival. Country songs aided in this survival, at least for my mother and step-ather.

One of the love songs I am obsessed with is “Y Sigues Siendo Tú” by Rogelio Martínez. In the years before my mother married my stepfather, my mother and I lived with five of my aunties, all of whom came from Mexico to make a living in Chicago. “Y Sigues Siendo Tú” became something of an inside joke for us because, as a toddler, I would belt the song’s lyrics of eternal love whenever it came on the radio, and whoever was driving would too. It’s another one of those ballads that I can’t help but grin through the entirety of, no matter the occasion.

While rediscovering Twain, I scrolled through her songs’ Wikipedia pages. Towards the bottom of each page, there were lists of all the cover versions. I was floored to read that “Y Sigues Siendo Tú” is actually a cover of “You’re Still the One.”

I immediately called my aunties and mother, asking if they were aware that two of the most nostalgic songs for us had always been one in the same. Some of them chuckled, having known since the songs came out. My mother, however, gasped with the same urgency that I did. As we hurriedly mumbled Spanish and English lyrics, we realized that they were indeed the same melody, only dressed in slightly different cultural angles. We were awash with awe.

This is all to say that, at their core, songs are vehicles of the feeling we attach to them. Some quiet part of me wishes I had never found out “Y Sigues Siendo Tú” is a cover of “You’re Still the One” because it confirms that the only difference between these songs (besides language, a slide guitar and a horn section) is the cultural context of Mexican pride or American assimilation. The versions themselves are still distinct, but my nostalgia feels gentrified.

I am as conflicted about this as I am about the country Western aesthetic itself. It is because colonial racism and Mexican pride are inherently connected by country music. It is because of various appropriations on Native and Mexican people that I have been asked, when dressed as a cowboy for Halloween one year, why I was dressing as “a Mexican.” It is because of this that Twain said she would support an overt racist but her Greatest Hits album still feels like love to me and my immigrant parents.

It is because of these appropriations that when I think of my stepfather, I think of him sitting on the couch after work in his worn denim — a painting of a horse above his head — as he watches a film where Clint Eastwood shoots at Mexicans and he roots for Clint Eastwood. As a kid, I’d sit by his side, enamored with the movie because he was — because I was proud to be the son of a cowboy. Nowadays, I am proud to be the son of un vaquero.

Header Image Courtesy of Shania Twain (@shaniatwain) on Instagram

NO COMMENT