With $500 per month, Chicago aims to help low-income residents.

Just over 5,000 Chicagoans are getting $500 a month in cash with zero stipulations, providing relief in light of a pandemic, shortages, layoffs, inflation and overall economic hardship. It’s called the Chicago Resilient Communities Pilot and it is the first government-run guaranteed income pilot in Chicago.

The pilot’s application launched in April and selected participants started receiving direct cash payments in July. The 5,000 participants are receiving payments until July 2023, a total of $6,000 in the year-long program. Participants were selected from a lottery of 176,000 applicants.

This program is just one of three guaranteed income programs providing cash assistance to Chicagoans. Applications for Cook County’s guaranteed income program closed on October 21 and, on a hyperlocal scale, the Chicago Future Fund, organized by a nonprofit called Equity and Transformation, launched a guaranteed income program last year geared toward formerly incarcerated residents of West Garfield Park.

Rachel Pyon, program manager of the Chicago Future Fund, welcomes the city’s guaranteed income program, saying, “I think it is great in the ways that they’ve been able to center low-income folks and communities that have been hardest hit by COVID.”

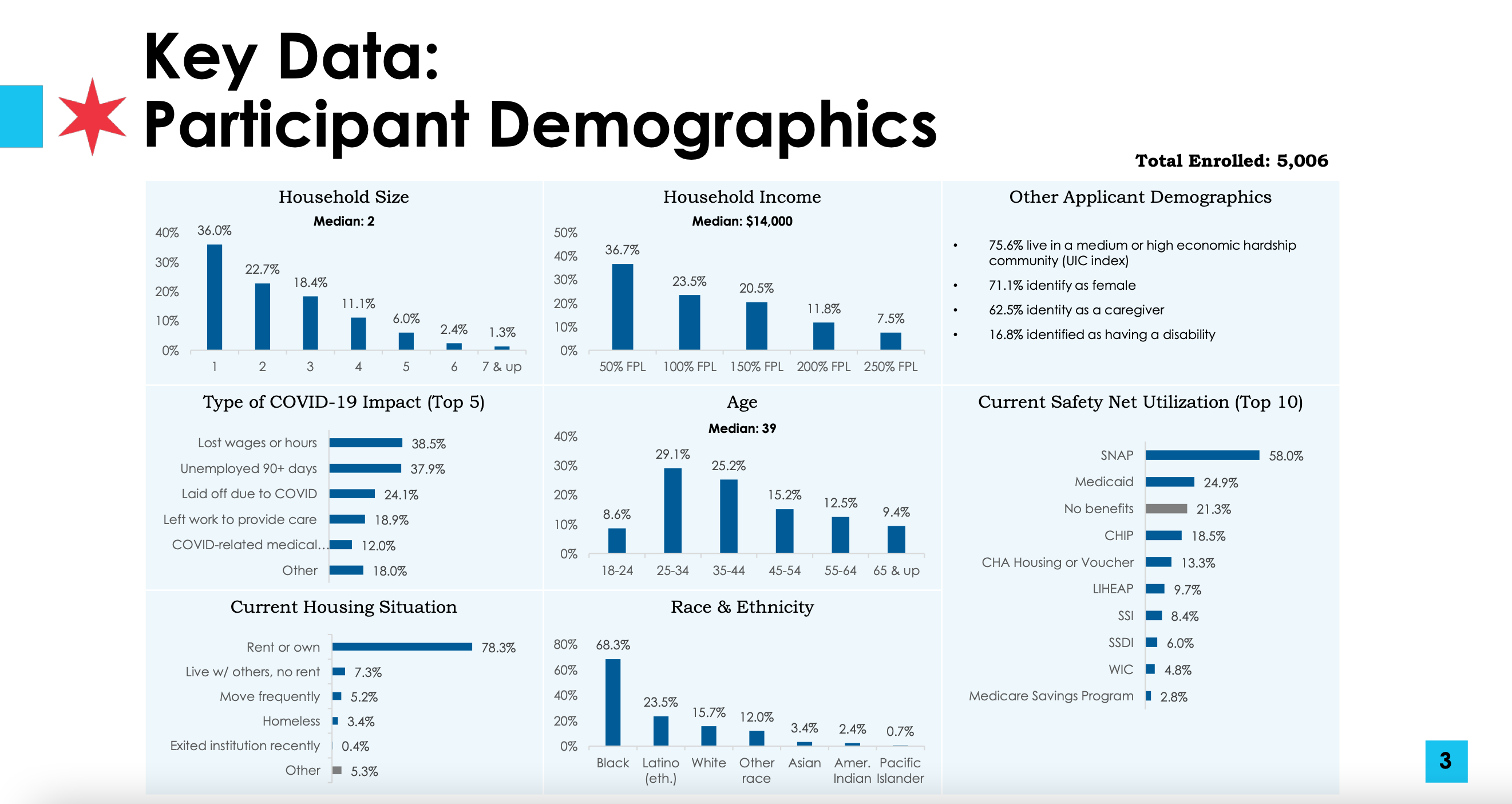

Of the 5,000 recipients, the program’s participant demographics report shows that the majority of participants are women, people of color, people living in poverty and/or people with caregiving responsibilities. The median household income of this group is between $13,500 and $14,000 per year, and participants were likely to be utilizing government benefits such as Medicaid, Chicago Housing Authority Vouchers and/or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

The pilot is just one part of the Chicago Recovery Plan aiming to help the city bounce back from the COVID-19 pandemic and other recent economic hardships. Guaranteed income, however, was introduced in the country years before it reached Chicago.

A brief history of guaranteed income

Guaranteed income in the U.S. started in Stockton, California, where, in 2019, Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs introduced the concept through the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED), which provided $500 per month to 125 residents for two years.

Since SEED, government-run guaranteed income programs of all varieties have piloted in Birmingham, Alabama, which geared their program toward single mothers. Atlanta and close to home in Evanston, Illinois, targeted low-income families.

Currently, guaranteed income programs are in the pilot stages. Some, such as Chicago’s, have just started while others, including SEED, recently wrapped up. As these programs start and end, critics of guaranteed income, and other basic income concepts such as Universal Basic Income, say that the extra cash each month makes people not want to work.

“Incentives are a powerful force. And there is no greater incentive than financial security and holding a job is essential to that end. When something comes easy, it is easily taken for granted. And while it would be nice to believe otherwise, giving cash handouts to every American incentivizes them to try that much less,” said Brittnay Hunter in an article for the Foundation of Economic Education. “By removing the financial incentive to work, the state is encouraging idleness, something contrary to the entrepreneurial spirit so deeply woven throughout our country’s history.”

Based on interviews conducted by Pyon, the $500 per month is not enough to de-incentivize participants in her program who are at similar income levels to those in the city’s program.

“[The participant] is really thankful that it hasn’t replaced her formal line of work, because she knows that it’s not enough to necessarily survive off of,” Pyon said about a participant’s feedback.

Most guaranteed income programs target those living well below local and federal poverty lines who may need the additional cash to help make ends meet. These do however jointly criticize guaranteed income and Universal Basic Income (UBI), though UBI does not have criteria for receiving cash assistance but guaranteed income does.

Critics of guaranteed income, such as Investor Business Daily, interchangeably used guaranteed income and UBI without distinguishing any difference.

At the core of the guaranteed income discussion is how these cash assistance programs are going to be funded. Each program is funded differently, whether that be private contributions, state funds or federal funds. Funding is dependent on each individual government and program if they decide to move beyond the pilot.

Who’s paying?

Chicago isn’t spending a dime of city money for the pilot program; federal funds are paying the way.

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) passed in 2021, giving local and state governments sums of money to use to help repair damages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and other economic hardships. Chicago received $1.9 billion in funding, and some of those funds are used to pay for the entire Chicago Resilient Communities Pilot.

Amanda Kass is an assistant professor at DePaul University’s School of Public Service and is researching how local governments are spending ARPA money.

“[ARPA] gave discretion to governments to be able to spend that money,” she said. “One of the kinds of eligible areas is around providing economic assistance to households … vulnerable to the economic impact of COVID.”

Due to ARPA assistance, Chicago had a simple avenue to get this program off the ground. However, ARPA money is not for long-term investments. It must be obligated by the end of 2024 and fully spent by 2026.

“I think the city of Chicago has created and framed the project as a pilot,” she said. “[They’re] not creating an expectation that’s going to be a recurring program. If they do this pilot, and they find that it’s an effective policy, then yeah, we’ll have to [start a] debate and discussion about if we make this a permanent program. And if so, how do we fund it?”

According to Kass, it is also likely that federal funding such as ARPA will not come back soon.

“We haven’t seen that kind of assistance or federal money that’s discretionary, in the way that our ARPA money is, since the General Revenue Sharing Program, which ended in the end of 1986,” she said. “At the federal level, there’s not a discussion about how we provide ongoing inter-governmental aid to state and local governments. From the federal government perspective, this is a one-time emergency situation funding.”

For any continued funding, privately, locally or federally, the Chicago Resilient Communities Pilot will need to produce extensive research from the pilot to show that guaranteed income should become permanent in Chicago.

Pilot Research

The Inclusive Economies Lab at the University of Chicago is leading the research for the Chicago Resilient Communities Pilot in support of the city’s guaranteed income initiative.

Misuzu Schexnider is a program director in the lab and is working on research, which involves quantitative and qualitative assessments.

Quantitatively, “We’re taking data that already exists about people and also comparing people who are participating in this program to people who applied and look very similar to both people [in the program], but they didn’t win the [program’s] lottery, so they’re not participating in this program. And thus, [we’re] making a comparison about these outcomes,” Schexnider explained. She says the lab is using quarterly surveys to measure mental health, stress and relationships, which are more difficult to measure.

Qualitative research will come through interviews, which the lab just started conducting though they have yet to release any findings.

“All of that will really help to provide a glimpse into what this program is like for the people who participated in it,” Schexnider said.

Four months into the 12-month program, Schexnider says the lab cannot make any conclusions yet. The lab will be releasing some household demographic data, such as education, credit scores, employment and wages, around the end of 2022.

Beginning in 2023, the lab will start a process evaluation using surveys and participant interviews.

“One of the things that we’re really excited about is to do focus groups, collect program data on and really better understand, did this program stay true to its intention to its design principles?” Schexnider said. “Did the outreach reach all the target populations that the city wanted to? Did the application feel accessible and easy and streamlined for people compared to other government applications that they’ve had to fill out?”

Looking ahead, Schexnider said the lab plans to look beyond July 2023 and ask participants about their plans when the program ends and if they received benefits counseling.

Pilot before policy

Guaranteed income research has a long way to go in Chicago, and impacts are yet to be determined from the current pilot. However, the vast amount of guaranteed income pilots across the country shows its popularity.

Pyon, who hopes to eventually see guaranteed income pilots become permanent policies, says this is an investment in underserved communities.

“Ultimately, it’s about believing that the best investment we can make is directly into the hands of the people,” Pyon said. “ I think a lot of times, guaranteed income is going to come across like, ‘Oh, this is just a fun experiment, like a fun, innovative idea that we can try out,’ which, sure, it can be, but I think people forget that it really is folks’ livelihoods at stake.”

As the Chicago Future Fund grows in conjunction with the city and county pilot programs, a permanent guaranteed income policy could potentially reach decision-makers throughout Illinois if government-funded pilots are deemed successful.

“At the end of the day, it’s about connection,” Pyon said. “It’s about investment, and it’s about really going deep with the people that have historically been pushed out. And so we’re really glad that we were able to play a part in that.”

Header Illustration by Samarah Nasir

NO COMMENT