Chicago and its Notorious Jazz – Looking at The Green Mill

At a velvet booth at 4802 N. Broadway, 55-year resident of Chicago Robert Foley and his son, Peter Foley, sit at the Green Mill watching The Chicago Cellar Boys.

“I used to come here with my father, and now I come here with my son,” Robert Foley said.

In a society today where hats seem to be only ever worn accompanied with a sports logo, certain parts of society remain wearing top hats and fedoras in a genuine fashion. Chicago’s jazz scene, for example.

Jazz and the Windy City first mingled in 1915 after people from New Orleans migrated to Chicago looking for work; with a lust for jobs in steel mills, factories, and stockyards, the sound of jazz followed. During this time, jazz was typically found in small local clubs on the South Side until it quickly became a popular ring in clubs all around the city.

Icons such as King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong were then inspired to play in Chicago, and ever since, Chicago’s jazz scene has flourished as a proud part of the city’s past and present.

The Green Mill Cocktail Lounge is a pronounced marker of the beginning of Chicago’s jazz scene when it was bought by Tom Chamales in 1910. During prohibition, the Green Mill served as a speakeasy and one of Al Capone’s hangouts. It is said that each night when Al Capone would enter Green Mill, the band would stop playing and perform his favorite, “Rhapsody in Blue” by George Gershwin. Capone would take his seat in the booth behind the short end of the bar; this way, he could clearly see whoever entered the club, be it friend or police.

The stage of The Green Mill. Photo by Kiki Dyball.

Although Green Mill no longer houses gangsters, it remains to be a distinguished jazz club in Chicago with almost identical characteristics to Capone’s time. After changing hands several times, Green Mill is now owned by Dave Jemilo, who bought it in 1986. The lush interior is reminiscent of the early 1900s as the original bar remains and the building has only been through slight renovations. Now, Green Mill’s legacy is brought to light through nightly performances with acts ranging from blues, jazz, big band orchestras and swing bands.

However, in more recent decades, jazz has digressed from America’s favorite music genre, and now generally appeals to a much smaller audience. As COVID-19 led to the closing of many businesses, it is safe to say that what the future of jazz in Chicago will be is an ominous question.

According to Chicago Cellar Boys trumpet player Andy Schumm, fewer people – specifically young people – have come out to Green Mill since the pandemic. Nevertheless, Schumm says jazz is too important in Chicago for it to truly be over.

“When I started playing professionally out of school … I was playing retirement homes, old people jazz festivals … that was all the work I could get,” Schumm said. “I was telling my colleagues [that] in ten years this will all be done because all of these old people will be gone … and now 15 years later I am doing better than I ever was.”

Assorted instruments awaiting for the musicians of The Green Mill. Photo by Kiki Dyball.

After beginning piano at age six and playing the trumpet throughout high school and at the University of Illinois, Schumm has lived a life infatuated with music. As he typically focuses on music from the 1920s to 1935, Schumm’s music carries a rather original sound of jazz compared to many other Chicago musicians who focus on music from the 1940s–1970s. Schumm’s Chicago Cellar Boys play at the Green Mill on Tuesday nights.

“I feel like my job for the hour or two hours that people are there is to make them … care about it while they’re there,” Schumm said. “I think the atmosphere of that place makes it possible for regular people to do it.”

Schumm expresses a sense of optimism and passion when considering the future of jazz in Chicago, and specifically awards Green Mill for their progressive, yet classic approach to running a jazz club. He emphasizes that musicians in the industry are incredibly supportive of each other, and his work life often blends in with his personal life.

Green Mill’s Monday night performer Joel Paterson feels similarly.

“I don’t play with anyone that I don’t like, musically or personally, because playing with them is like a conversation,” Paterson said. “I like to play with musicians who are very sensitive and conversational and interact with what you’re playing.”

Joel Paterson, right, plays with another musician at The Green Mill. Photo by Kiki Dyball.

Paterson has worked in Chicago’s jazz scene at the Green Mill for 25 years, and he specializes in jazz, blues and western swing. His band often likes to play tunes from the Beatles, and his infamous steel guitar helps to bring a unique swing to their music.

Paterson also says that with jazz being a more sophisticated style of music — meaning that jazz musicians are typically very studied and technically talented — it is nice to see that the younger crowd is still attracted to the genre.

“It was nice to see people like you come out and listen to jazz,” Paterson said. “You always need that influence of younger people that get into it so it doesn’t just totally die and people think it’s out of fashion.”

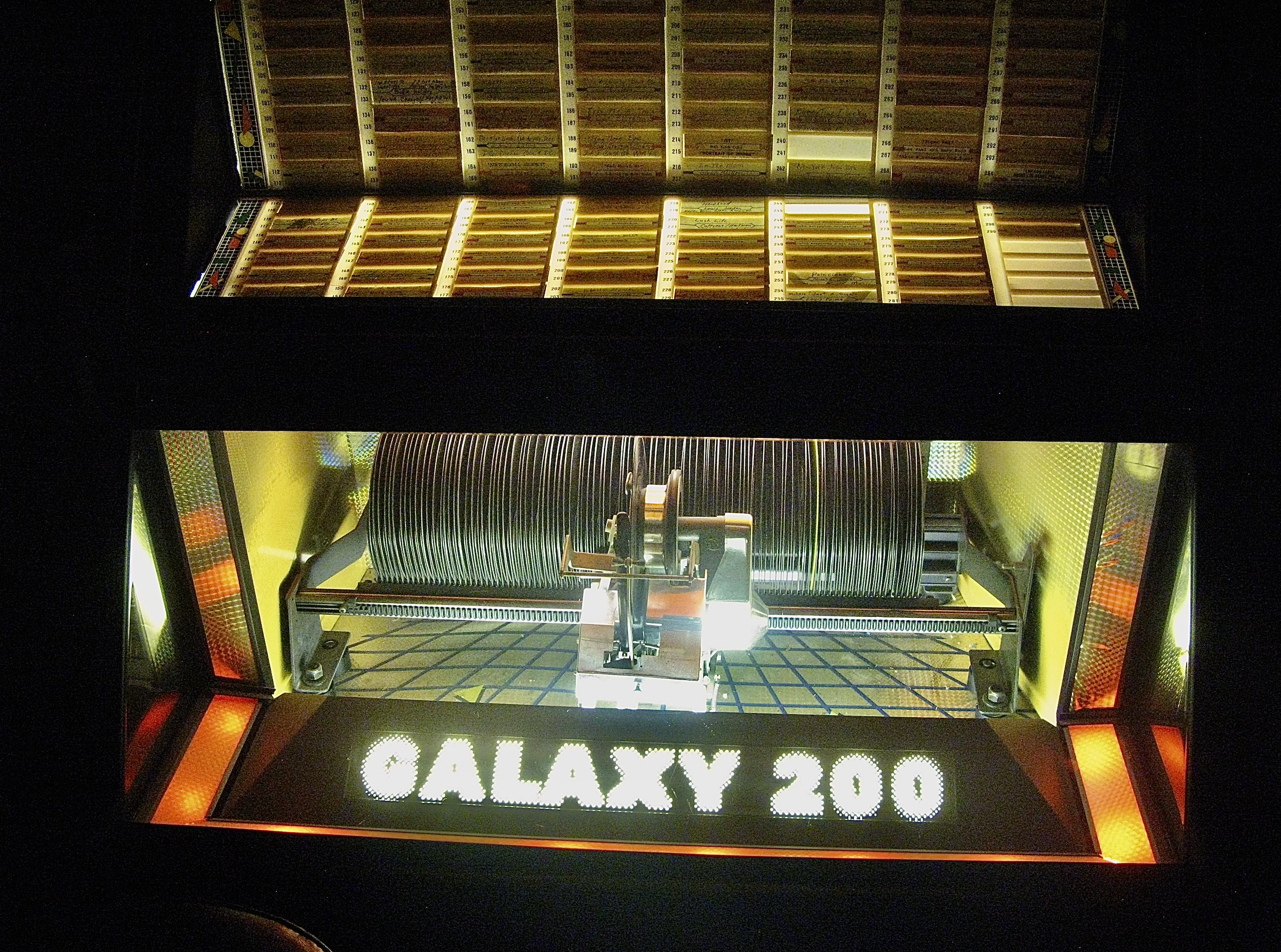

A jukebox with hundreds of selections of songs that play at The Green Mill. Photo by Kiki Dyball.

Chicago is notorious for its historic jazz scene; thus, the thought of the historic Windy City without its current jazz culture and talented musicians is unfathomable. To put it frankly, jazz will remain a part of Chicago’s culture for as long as musicians wish to keep playing, and it does not seem they will ever be ready to give it up.

“For me, jazz music is my entire life,” Schumm said.

Header image by Kiernan Sullivan

NO COMMENT