Gender identity isn’t black and white, and it isn’t just male or female, either

“It’s weird. I call it my weirdness.”

The “weirdness” started with a YouTube video.

Their senior year of high school, Grace Walker watched the coming-out story of transgender YouTuber Alex Bertie and began to draw some significant parallels between themself and Bertie, who spoke in his videos about feeling uncomfortable with the gender with which his body presented and the comfort he felt when someone would refer to him as male. All of these parallels related to the internal feeling and external expression of gender. This is was the catalyst for Walker’s journey as a non-binary person.

Walker would get misgendered as male on occasion, and they remembered not caring or even finding it funny. Classmates who knew Walker as a girl would assume they were a lesbian, which made them start to question their sexuality, but that didn’t feel right to them. Walker knew this had nothing to do with the people they felt a physical and emotional attraction to.

Even though these parallels relating to expression of gender existed, Walker still didn’t feel like they could completely relate to the story of Bertie.

“I was pretty sure I wasn’t totally trans,” Walker said. “But then I found out gender fluid was a thing, and that made sense to me.”

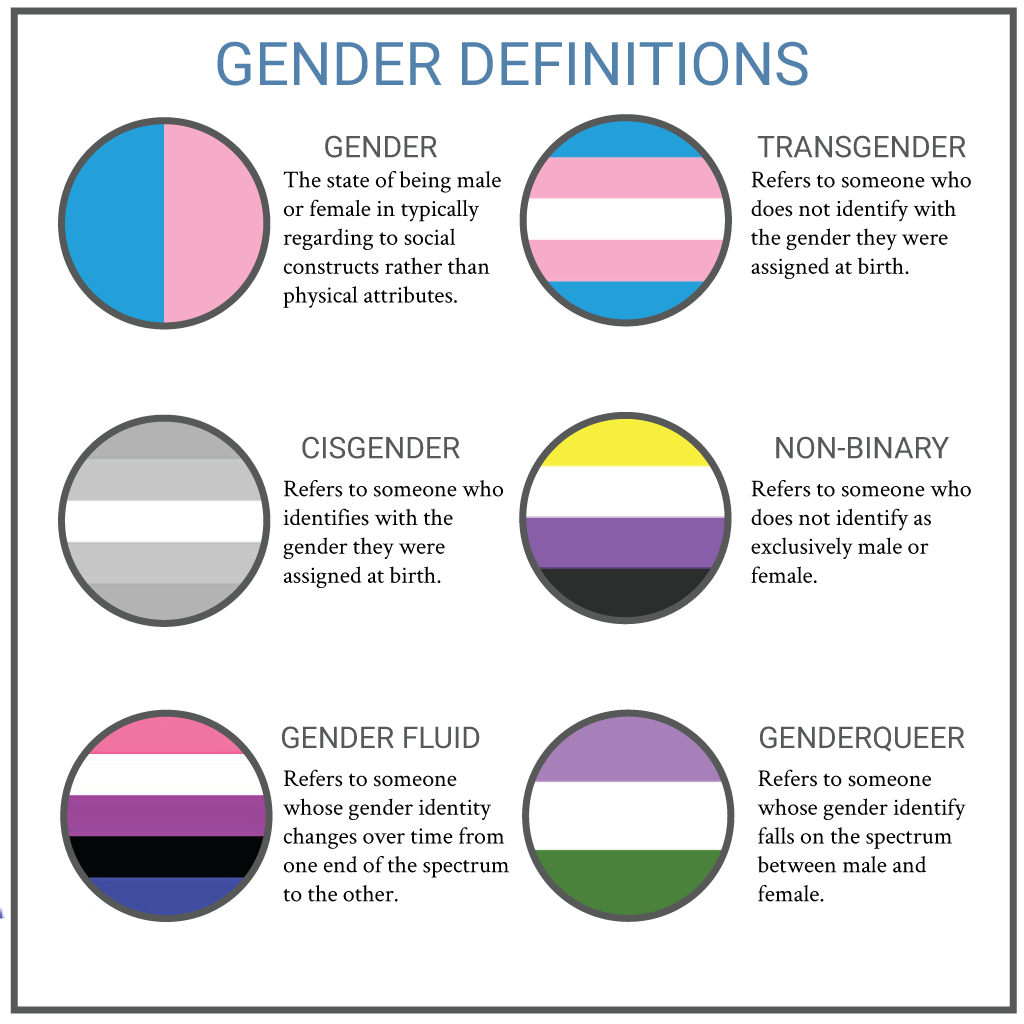

When Walker tells people they are gender fluid, they are referring to their gender identity. Gender identity falls on a spectrum that is bookended by male and female identities, but there are many in between. Gender fluid is one of those identities that falls in between. It means that Walker doesn’t have a static identity. One day they may feel completely feminine, on another they may identify as a man, and on another they may be some mix of the two.

He, Her, Their: Using preferred pronouns

People with different gender identities may choose to use pronouns other than he or she. Walker isn’t particular about what pronouns are used to identify them, but since their day-to-day identity can change, this article will use the pronouns they, them and their to describe Walker. Walker also uses the names Grace and Charlie; they aren’t particular about that, either.

Walker’s story isn’t particularly unusual. Many other people identify as something other than male or female. These identities are categorized by the umbrella term non-binary identities, meaning they break the idea that gender has to fall in a binary.

Joey Shelley, a PhD student at University of Illinois Chicago, also identifies as non-binary, but they use the term genderqueer, which means they consistently identify as the same gender, but that gender is both male and female.

Shelley spent most of their life being referred to as “she.” They weren’t completely comfortable living a life being identified as female, but they didn’t know there was another option until they were researching trans identities to be a better ally to a friend who recently came out as transgender.

“I found the term genderqueer, and I thought, ‘Wait a second, you mean everyone else doesn’t already feel like this?’” Shelley said. “This is me. This is me all over. This is all the things I’ve never understood. This is the disconnect I felt with femininity. This is the disconnect I felt with masculinity. I am not one of these things. I am these things mushed together in some weird recipe for gender non-normativity.”

Shelley likened their discomfort in their gender to being stuck in an airplane seat with no room to move or relax. To them, finding a non-binary term to identify with was like being moved to an exit row where there was more room to move.

“Finding genderqueer was finding room,” Shelley said. “Instead of being squished into a label that didn’t make sense with who I was, I just got rid of it and the idea that I needed to be more womanly to be part of womanhood or be more manly and be completely trans masculine. I didn’t have to choose.”

Men’s rooms and women’s rooms: Living in a binary world

I realized that I didn’t have to stay within this label that I never felt comfortable with and I never felt described me.

DePaul University in Chicago has programs and policies that acknowledge non-binary gender identities, and most of those policies are spearheaded by the Office of LGBTQA Student Services in the Center for Identity Inclusion and Social Change. Katy Weseman, the student services coordinator, works with students who identify as non-binary as well as other students. Weseman is a cis woman, meaning she identifies with the gender she was assigned at birth.

According to Weseman, people assume that gender identities are very easy to place, and many people still believe that there are only two options for gender identity.

“There are as many gender identities as there are people, and unfortunately we like to put things in really rigid boxes,” Weseman said. “But really when people start exploring, or thinking, or talking about their gender, it’s often way more complex.”

Elon Sloan also works in the Office of LGBTQA Student Services at DePaul. They work as an office assistant and also facilitate and founded the discussion group “Gender?” that is run through the office.

Sloan identifies as trans and non-binary, and they don’t use any more specific terminology to identify their gender.

“I realized that I didn’t have to stay within this label that I never felt comfortable with and I never felt described me,” Sloan said. “I’ve spent so much of my life thinking that there was nothing that could release me from that and I was feeling very dysphoric about it.”

Dysphoria is defined by Merriam-Webster as “a state of feeling unwell or unhappy” and has been used in transgender and non-binary communities to describe the overwhelming feeling of discomfort with one’s own body.

For the first six months after I started going by a different name, I don’t think I wore a single skirt.

Because of their long-standing discomfort with presenting as the gender they were assigned at birth, Sloan didn’t spend a long time questioning their gender identity. They discovered the term non-binary in the latter part of middle school and quickly embraced it.

“From the moment that I understood what gender was, I realized I was trans,” Sloan said. “And from the moment that I fully understood what trans was I realized I was a non-binary person.”

As a whole, American society is focused on placing people into simple categories like male and female. Because of this, Sloan faced people who were dismissive or insensitive about their personal gender identity.

“I feel like there are many different levels of challenges,” Sloan said. “I think that people feel like it’s not real, and they feel like it’s academic. I’ve literally had someone ask me if I read a certain book and that changed my gender identity.”

Many people aren’t even aware that non-binary identities exist, or they aren’t willing to accept them. The lack of acceptance can be seen through use of pronouns.

“[One of the struggles non-binary people face] is people not understanding or people not being respectful,” Weseman said. “Something that I see a lot with students who use they, them and their pronouns is people refusing to use those pronouns. They’ll just default to the way that they read the person, which is often the sex the person was assigned at birth.”

Shelley altered their gender presentation away from clothing that fit their birth-assigned gender because it would be easier for people to see their identity as valid. Instead of dressing and presenting as a female, Shelley began to dress more masculinely. They did this not for themselves, for for the sake of other people understanding, which led to its own complications.

“People have a hard time with non-binary identities,” Shelley said. “For the first six months after I started going by a different name, I don’t think I wore a single skirt. I don’t think I wore a dress. I basically dressed in masculine or non-gendered clothing. It was so hard to get people to acknowledge what I was already asking of them that I felt like if I was doing a mixed-gender presentation, they might question the legitimacy of my claim.”

Identity erasure is common for people who do not fit into the gender binary. Identity erasure is when a person or groups of people refuse to acknowledge the existence of an identity. This leads to a culture of exclusivity where a person must fit predesigned specifications to be included in that society. Ways non-binary identities are excluded from common spaces can be seen in phrases like “ladies and gentlemen” or “boys and girls.”

“What I notice with non-binary students is your baseline threshold of what to expect, you expect not to be included,” Weseman said. “That’s where I feel like people are at, unfortunately, such that it’s exceptional that people would include [non-binary people]. How sad is that? And I think a lot of that speaks to the need for a larger culture shift.”

Examples of erasure can also come in different forms like structural spaces. Many places don’t have gender–inclusive facilities like restrooms or locker rooms, which forces non-binary people to choose a gender.

States like North Carolina instated so-called “Bathroom Bills,” which mandate that people must use the bathroom that corresponds to the sex they were assigned at birth. While protests arose claiming these bills are anti-trans, the bills also affect non-binary people who may identify and outwardly present differently each day.

Unexpected reactions: Coming out to family and friends

Sometimes the struggles non-binary people face are not with strangers or society. Coming out as non-binary to family can cause tensions at home.

Shelley wasn’t ready to have a discussion about gender with their parents when they posted a video of themselves in a dance competition. Their parents enjoy seeing Shelley dance, and they just tagged their parents in a video on Facebook. Shelley didn’t remember that in this competition, they were announced as “Joey” rather than by their birth name.

Shelley’s parents noticed, and they immediately prompted a conversation despite Shelley’s efforts to put it off. Since Shelley was at work at the time, and their parents demanded to talk about it, Shelley ended up explaining their gender identity through a text message. That was a year ago.

“They still don’t get it in a lot of ways,” Shelley said. “My mom feels like I am rejecting what womanhood is because of her, which is super unfair. That’s not what’s happening.”

While Shelley’s mother hasn’t always been completely understanding of their gender identity, she does make efforts.

“My mom has tried to embrace it in the way that she does, which means sewing me bowties for Christmas instead of skirts and shopping in different departments because she shows her love through gifts,” Shelley said.

Walker came out to their parents in a more intentional way. They came out to their parents as gender fluid about six months after finding the term gender fluid. They expected them to be supportive, but it still was difficult to find the right time. Instead of sitting their parents at the table and telling them, Walker went a different route. As they were heading to their room in the basement, Walker shouted from the stairs, “And by the way, I’m gender fluid.”

Then they went to bed.

The next morning at the breakfast table, Walker’s mother asked them what they said from the stairs, and that started the discussion. Their parents immediately accepted them, but their brother had one question: “What does that mean?” Once they explained that it meant they weren’t always a girl or always a boy, their brother went back to reading his book.

The name change made me suddenly worried that they were going to change, be a different person.

To come out to their friends, Shelley used Facebook.. Two years after first identifying as genderqueer personally, they made a secret group including people they felt they could trust that wouldn’t disrespect their identity. Shelley told them that they would prefer to be called Joey, and they asked the members of the group to inform others if the situation came up.

Overall, Shelley feels their friends have been supportive.

Shelley’s spouse has also been supportive of their gender identity. They were already married when Shelley started identifying as genderqueer, but that hasn’t impacted their relationship. Although, one day, when Shelley expressed that they were considering top surgery, a procedure that removes breast tissue, their husband Braden Nesin said he might not feel the same way about them with a different body. Shelley was understanding of this, but Nesin retracted that thought a week later, saying that he married them for their brain, not their body.

Although both Nesin and Shelley say their relationship hasn’t been effected by Shelley’s gender, Nesin did become concerned when Shelley decided to change their name to something less feminine than their birth name.

“The name change made me suddenly worried that they were going to change, be a different person,” Nesin said in an email. “They didn’t, they’re still the same person I fell in love with.”

Shelley isn’t comfortable being open about their gender identity in every environment. They are not out at their college because they may face discrimination.

“To be honest, I’m probably scared for nothing,” Shelley said. “I don’t think anyone would intentionally jeopardize my career, but I don’t want to find out.”

Sloan experienced coming out in a neutral way. They began openly identifying as non-binary their freshman year of high school, and it never became a topic of conversation.

Sloan did experience situations where people would invalidate their identity. People would debate with them the existence of non-binary identities or tell them that their identity is academic and doesn’t exist in the real world. Sloan said this removed their ability to feel affirmed in their identity.

Many people do not understand that gender can exist on a spectrum rather than in a binary. According to Weseman, it is easier for people to understand identity changes when it is on a linear and binary level. She credits this understanding in part to growing media attention on trans issues and trans people such as Caitlyn Jenner.

In Weseman’s ten years working in higher education, she has seen “tangible growth” in areas relating to education around pronouns and gender inclusivity.

Although there has been progress in terms of non-binary gender visibility, non-binary people are often expected to justify their identity and existence to people who don’t identify as a gender other than male or female.

“The burden of education is placed on the person with the identity,” Sloan said. “And that can be very hard when you are just trying to have your identity acknowledged, and you’re just trying to get through your day and not have people constantly contest your identity to you.”

Part of the struggle non-binary people face is due to immediate misidentification. Since many people see others on a binary of male and female, initial assumptions are made about a person’s gender based on their physical appearance. This leads to dysphoria.

Shelley chooses their clothing to fit their gender identity by mixing feminine and masculine clothing like a miniskirt and a bow tie with a button up shirt or by wearing gender-neutral clothing like jeans and a t-shirt. Despite this, Shelley still doesn’t feel like the way they look represents their identity.

“If I were a vaguely androgynous, female-bodied person with less than 42 inches of booty, I might not even be considering any kind of surgery,” Shelley said. “It would more be about presentation choices, but my body I.D.s me as female far faster than I want it to.”

While Shelley has considered top surgery to make their appearance less feminine, they don’t see that as their only option. Currently, Shelley chooses to wear a binder on most days. A binder is an article of clothing that is used to minimize the appearance of breasts. They are often uncomfortable, as they are made of extremely tight nylon or spandex. Binders can even be dangerous to wear for extended periods of time because their tightness restricts the chest’s ability to expand and take deep breaths.

“The mental comfort of wearing a binder is so much higher than the physical discomfort,” Shelley said. “I’m less aware of my body as an impedance. I do a much better job of forgetting about my body when I wear a binder until I can’t breathe, which is the problem.”

Another option for people experiencing dysphoria is hormone replacement therapy (HRT). HRT is used for people who want to physically transition from one end of the gender binary to the other. People assigned female at birth can take testosterone to achieve a masculine appearance, and people assigned male at birth can take estrogen to achieve a feminine appearance. However, this option is not often used by non-binary people because most non-binary people aren’t looking to physically look like either end of the gender spectrum.

Sloan also likes to display their gender identity using masculine and feminine clothing. They also wear a binder on most days, except for when it could affect their asthma, like in the colder months. Sloan hasn’t medically transitioned and doesn’t intend to.

“I think for a lot of people there’s a fascination and sort of exoticized focus on surgery,” Sloan said. “So many people don’t go on hormones, or if they do, they don’t have surgery. A medical transition is not for everybody.”

When dressing, Walker tends to focus on comfort. They wear men’s jeans most frequently because they are more comfortable than jeans designed for women, and they like the deeper pockets. They occasionally wear dresses, but they don’t find the skirts very comfortable. Since Walker is gender fluid, their outward presentation of their gender is more dependent on their identity that day.

The name game: Choosing an identity

Part of Walker’s gender presentation is their name. Walker was named Grace at birth and is still uses that name, but they also use the name Charlie to fit the days when they felt more masculine.

“I went through a big, long list of names and narrowed it down to a few that I thought were really cool or I wouldn’t mind being called,” Walker said. “I talked to my friend Noah, and I talked to my friend Celestia, and both of them had insights. And we kind of ended on Charlie because it was masculine, but it wasn’t excessively masculine.”

Shelley also adopted a different name from the one they were given at birth.

Shelley’s name comes from a penname they created for a blog. They used the name “Joey G. Lovelace,” which is in homage to actor Joseph Gordon Levitt and mathematician Ada Lovelace.

Shelley recently completed the legal process to officially change their name to Joey Shelley, which includes multiple forms and fees totaling around $500.

While Walker chose the name Charlie while they were still in high school, it wasn’t until arriving in Chicago that they decided to first use that name.

“Charlie did exist on the first day of school here at DePaul. It was a split-second, last-minute decision to be like, ‘Hi, my name is Grace. Or Charlie.’ It was very much like a moment of panic. Like, if any time was the time to do it, the time was now,” Walker said.

Walker still goes by Grace at home in Minnesota. They use the name Charlie frequently at DePaul but not all the time, so they didn’t realize the impact that their gender inclusive name could have.

“I didn’t really notice it until I went back home for break, and I was just Grace and I was a female for two-and-a-half weeks. And then I came back and somebody called me Charlie, and I’m like, ‘Say that again.’ That was really cool.”

NO COMMENT