Chicago’s rat problem, by the numbers

These days, it seems like everybody in this town has a rat story. Aiden Kent’s picks up in the alley behind a Lakeview apartment.

Kent, a junior at DePaul University, is resourceful – an activist and a thrifty one at that. While doing some dumpster diving for a cardboard sign before last week’s protests, they wound up in company that probably should have been expected. Pulling the top off a recycling bin, Kent was greeted by two rats; plump, sitting and “staring into my soul, as if I was interrupting a meeting.”

“There was no fear there,” Kent said. “I feel like that has to be true across the city.”

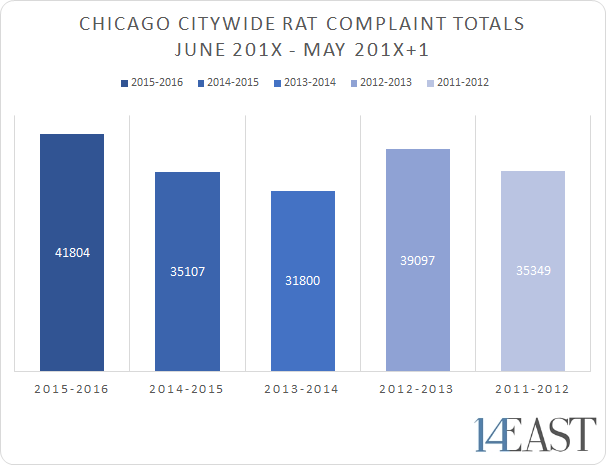

Kent may not be wrong. For Chicago – named the nation’s rattiest city by a national pest control company in 2013 – our rodent problem doesn’t seem to be going anywhere, even as Mayor Rahm Emanuel doubles down on sanitation crews devoted to “rat abatement.” Data collected by the city shows the number of rat complaints on track to be as high (if not higher) than they were in 2012, the rattiest year on record since the creation of Chicago’s data portal in 2010.

Examining citywide totals between June and May of the following year, the past 12 months has seen the highest amount of rat complaints since Chicago began posting its data online in real-time: 41,804. However, that doesn’t mean 41,804 residents filed complaints, or that 41,804 complaints were filed from separate addresses. In an analysis performed by Chicago Tribune in October 2015, they reported that one woman had called 311 almost 90 separate times to report rats on her property.

And even though the quantity of rat complaints doesn’t necessarily indicate the magnitude of infestation, it’s one of the only methods available to count the furry pests; rats don’t exactly line up for censuses, and the complaint-driven model is what the Department of Sanitation Services (DSS) uses to divvy up its resources. As we move into summer months and complaints begin to climb, residents are gritting their teeth in preparation for what’s to come.

“In the last two years, I’ve really noticed the frequency increase with rats,” Kent said. “You see them walking down the street in the middle of the day, eating lunch on your porch. Just, you know, generally being intrusive.”

“I named the one in my alley Goliath because he’s the size of about three to four full-grown rats,” Mary Catherine Nedbalski said. “He’s cool though, nothing can kill him.”

Nedbalski, a senior at DePaul, lives on the border of Lakeview, Wrigleyville, and Boystown. Through Facebook, she described seeing the alley next to her apartment littered with rats at one point this spring. A few weeks after her landlord set out traps, only Goliath remained.

“I’ve seen him run into one of those older rat traps and be so big that he broke it, and then he escaped up a pole,” she said. It’s not hard to imagine Goliath picking up the poison pellets scattered on the ground as chewing tobacco before using a nearby dumpster as a spittoon.

Infestation is in some ways an equalizer. For one of the most segregated cities in the country, rats aren’t something that Chicago’s more affluent quarters can avoid; in fact, the comparative abundance of restaurants on the North Side makes it in some ways more hospitable. DePaul’s Lincoln Park neighborhood is no exception.

In March, DNAinfo Chicago reported that the company in charge of tearing down Children’s Memorial Hospital in Lincoln Park was warning nearby residents to expect an “awful” influx of rats once the walls came tumbling down; construction often sends them scurrying in every direction, and the site is likely home to a large colony.

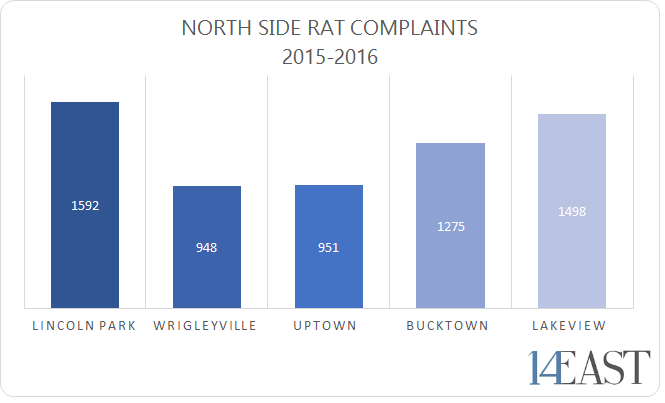

While the hospital still stands, Lincoln Park residents have continued to complain – both officially to the government and casually between friends – about the growing audacity of rats. Data from the city shows that the 60614 ZIP code has nearly the highest rate of rat complaints in the city, let alone the North Side.

By the numbers, Lincoln Park has netted the highest amount of rat complaints in the last 12 months on the North Side. That’s impressive, considering this year’s construction at Wrigley Field and the Wilson Red Line stop (in Wrigleyville and Uptown, respectively) which increased resident complaints in the months during and after the work, according to DNAinfo Chicago. How Lincoln Park’s numbers will look after the hospital actually comes down is anyone’s guess, although it’s hard to imagine complaints will go down before they go up.

However, Lincoln Park is also one of the most populated neighborhoods on the North Side. Dividing the number of complaints by the number of residents (according to the 2010 US Census), we can arrive at a rough estimate of an adjusted rate – a ratio consisting of complaints per resident, or a tentative percentage.

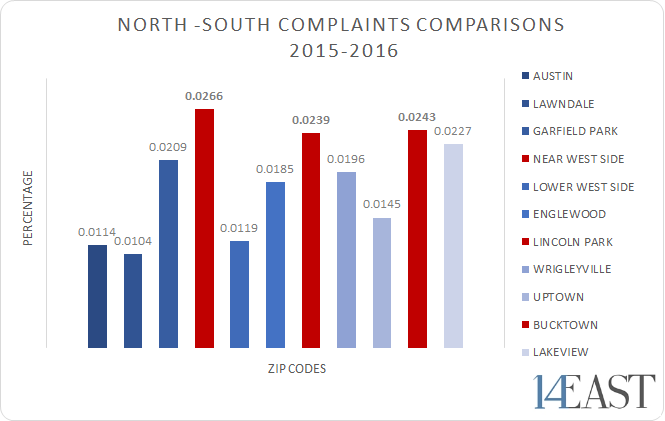

Analyzing the data between ten neighborhoods on the North, South and West Sides, Lincoln Park still manages to stand tall relative to its population. For every resident, 0.0239 rat complaints were filed with the city. The only ZIP codes that beat Lincoln Park (60614) in this metric were Bucktown (60622) and the Near West Side (60608). Bucktown managed to score a 0.0243 complaint-to-resident rate, while the Near West Side found itself with 0.0266 complaints per resident.

Looking at the chart, there also appears to be a disproportionate weight on the North Side. This is borne out by both the sheer number of complaints as well as the comparative ratio; while a cumulative 6,264 complaints were filed by the North Side neighborhoods included in this analysis, only 4,848 were filed by the South and West Side neighborhoods. Accounting for population, the North Side’s rat rate was about 0.0209, while the South and West Side came in significantly lower at 0.0146.

Despite that, the response time taken by city crews tends to lag if you don’t live north of the Eisenhower Expressway; the Chicago Tribune noted in their October analysis that, on average, cases were closed after 25 days for the Near West Side but after only 14 for the Gold Coast and Streeterville. The city’s self-prescribed goal is to get most complaints dealt with in five days. This isn’t necessarily evidence of neglect, however; crews can only bait a property with the permission of the homeowner, so the solution often depends on someone being home during the day.

However, as the rate of rat complaints continues to rise for its third straight year in Chicago, residents have to ask: is a solution really a solution if the problem is getting worse?

As Edward Evins walks down his alley on trash day in Lincoln Park, his mind bounces between two words: rats and cats.

Evins had dealt with rats. He was familiar with their ways. Before he’d jumped into DePaul’s academia as a visiting professor in the department of Writing, Rhetoric and Discourse, he’d owned a restaurant in the northwest suburbs of Chicago. He’d seen a few of them in his time, but only once actually inside the restaurant. When traps failed, he’d arranged an overnight sting with a few employees (complete with camouflage, crossbows and BB guns), and together slayed what turned out to be a rugby ball-sized monster.

But now he was thinking about feral cats, unleashed on their natural prey. That was the solution the city seemed to be considering now. What were people supposed to do when the cats became the problem? Bring in coyotes? And then wolves for the coyotes? And bears for the wolves?

And then he heard scratching – a lot of scratching – from his trash can. As he gingerly reached for the top of the bin, he planted his feet.

Six rats. Plump with points for eyes, jumping for the top ridge of the bin, sliding down by their claws after every attempt. Evins had to laugh as the scene played out in front of him: this was nature, with all the glory and perpetual motion of its stubborn, stupid persistence.

He kicked the bin over and watched each rat fly off in a different direction. He reconsidered cats.

Header image: a warning posted by Chicago sanitation services, alerting residents in Andersonville about a nearby infestation (Brendan Pedersen)

Charts compiled using data from Chicago’s 311 City Data Portal and designed by Brendan Pedersen.

NO COMMENT