After Massachusetts resident Amanda Nguyen was sexually assaulted, she learned her state has a 15-year statute of limitations for rape. Yet untested rape kits could be destroyed after six months. So every six months, survivors like Nguyen have to request an extension if they want their kit preserved.

Sexual assault survivors have consistently been subjected to intense scrutiny and uphill legal battles. According to RAINN (Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network) out of 1,000 rapes, only six offenders will spend even a day in jail. The CDC reports that 25 million Americans, roughly the population of Texas, are survivors of sexual assault.

Rape kits collect DNA and can identify rapists in an investigation but aren’t tracked by any federal agency. This means that it’s up to individual states to determine how kits should be handled, if they should be tested, and how kits are monitored by either law enforcement or survivors.

Nguyen founded Rise, a nonprofit dedicated to working with state legislatures and the U.S. Congress to implement the Survivor’s Bill of Rights, applicable in federal cases of sexual assault. President Obama signed the bill on October 7.

The Survivor’s Bill of Rights ensures the right to maintain a rape kit free-of-charge to the survivor for the length of the statute of limitations. The survivor must also be informed of the processing results of the kit and be notified 60 days before it is destroyed.

“Women like Amanda Nguyen give me hope,” Gabrielle Caro Nash, a social justice blogger, tweeted her praise for the Survivor’s Bill of Rights immediately after it was signed into law. “The only impediment I can foresee is a capital willfully ignoring the needs of the many…Given that this bill managed to pass through both the Senate and the House of Representatives with bi-partisan support, I believe this country is moving forward.”

The law also amended the Victims Crime Act of 1984, ensuring “the right not to be charged fees for or otherwise prevented from pursuing a sexual assault evidence collection kit.”

“It’s ridiculous that anyone would ever have to pay for their rape kits, so this is definitely a step in the right direction,”Hannah Retzkin, DePaul’s sexual and relationship violence prevention specialist, said. “In Illinois, a survivor shouldn’t ever receive a bill anyway.” Retzkin provides direct emotional and physical support to survivors and has been trained as a rape counselor at Rape Victim Advocates.

In 2015, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan pushed for the Sexual Assault Survivors Emergency Treatment Act. Effective Jan. 1, 2016, the law prevents sexual assault survivors from receiving bills for medical examinations and expanded medical and police training related to sexual assault.

Still, Illinois is plagued with both inconsistent training and insufficient funding.

“I think what would be the most beneficial to survivors if there was a standard of training around sexual assault, specifically medical and law professionals. What ends up happening is that response from go-to institutions can be unpredictable,” said Sarah Layden, director of advocacy at Rape Victim Advocates, a Chicago-based nonprofit, “For example, in Illinois, nurses don’t have any training on sexual assault in nursing school. So you could legitimately have a nurse that’s never done a kit in their lives.”

In Illinois, we do have Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs) that go through 40 additional hours of training in order to be more equipped to offer survivor patient care and complete forensic evaluations. But SANEs aren’t at every hospital and don’t exclusively work with sexual assault survivors but with other patients as well.

“That training is not required by all emergency room nurses. You can have a nurse that’s gone through the training somewhere in the hospital, but that nurse isn’t necessarily the one doing the kit if the hospital doesn’t ensure it,” Layden said. “So if they don’t have an on-call SANE program that can be an issue.”

The exam itself collects any and all evidence the survivor consents to, meaning it’s incredibly invasive. Retzkin, DePaul’s specialist who works closely with survivors, noted she’s accompanied a survivor to an exam that took more than five hours.

“So the kit takes time, and then they need to decide if they want to report it. Right now, they have two weeks to decide if they want to report, but there’s new legislation proposed so that they could have five years to report,” Retzkin said. “And it’s a big decision. Whenever someone experiences sexual violence, they have ownership of the narrative and once they share the story, they lose control. It’s tough and traumatic and not a decision to take lightly.”

Plus, rape kits in Illinois take about two years to be tested, an “excruciatingly long turn around time” according to Layden. In June 2016, there were 3,514 backlogged kits waiting testing in Illinois. Comparatively, Texas released a report by their state crime lab in 2016 totaling their untested kits at 19,018.

There are two different types of backlogged rape kits. One, the kit is awaiting testing at a crime lab. Two, the kit remains ignored, untested, and collecting dust somewhere since it wasn’t until 2011 that police departments had to send in rape kits to be tested under the Sexual Assault Evidence Submission Act.

Illinois is one of the few states to mandate rape kits are tested at the crime lab once evidence is collected. In other states, rape kits are tested at police discretion, which may be dependent on budgetary restrictions or the narrative (i.e. credibility) of the sexual assault.

“When police just don’t believe the victim, the kits just sit there, unreported. It’s estimated there are 400,000 of these backlogged kits,” Deanne Benos, executive director of Test 400k said.

Test 400k is a Chicago-based national nonprofit aimed at eliminating backlogged untested kits by advocating and initiating rapid DNA analysis. According to their website, it costs about $1,200 to analyze a kit, meaning to test those estimated 400,000 kits would total about a half a billion dollars.

“That’s why we’re called 400k, to symbolize what’s out there,” Benos said.

Following the Sexual Assault Evidence Submission Act in 2011, Illinois cleared their backlog over a period of three years. However, the law didn’t specify when kits are to be tested by, only when and if sufficient staffing and resources are available.

“The third part of the legislation only gave guidance but didn’t require that depending on the budget, kits should be tested in six months. The key is that they couldn’t pass the bill [if immediate testing were required] because the state didn’t have money,” Benos said. “If the state had the money, they should try and test in six months.”

At the time of the bill’s passing in 2011, the state had a budget deficit of $12 billion, in 2016, we’re at $8 billion. If the bill had included a clause on expediting kits or even testing them in a few weeks, it may have been more difficult to pass since kits are tied to state funding.

“There is no requirement that they test rapidly or with priority,” Benos said. “So it just shows that rape isn’t a priority, it’s a second-class crime to many people in our state.”

Because of the long waiting time, it’s not uncommon for police to pursue other areas of the crime, instead of the sexual assault, in order to get justice. For instance, if the survivor was also robbed, this can be an easier and more accessible avenue to prosecute. Yet, Benos questioned, “What kind of world do we live in where a robbery takes precedent over a rape?”

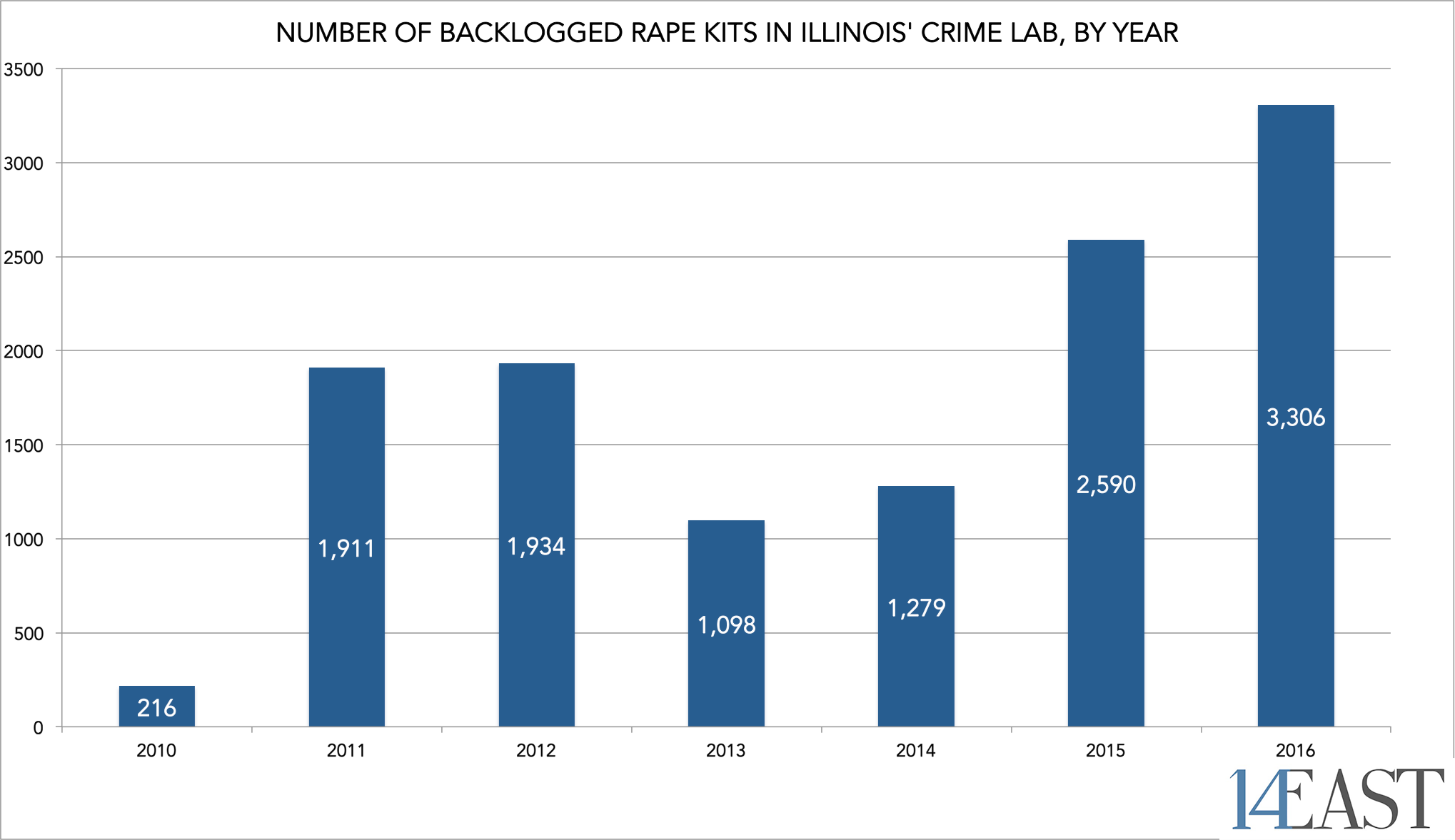

According to Illinois State Police’s (ISP’s) DNA accountability reports, the backlog at the crime lab was seemingly declining prior to this bill’s mandates. The crime lab had reached an all time backlog low of 128 cases in 2009 simply because police weren’t required to test kits.

Afterwards, there was a 68 percent increase in submitted rape kits.

Data from Illinois State Police (ISP) Yearly Accountability Report

In June 2016, there were 62 forensic scientists employed at the Illinois crime labs, down from 68 in 2015. On average, they’ve lost 12 scientists each year since 2009, though Brenda Danosky, ISP’s DNA Project Manager, says that Illinois’s recent budget issues haven’t impacted staff.

According to ISP’s 2016 DNA accountability report though, “failure to maintain the necessary staffing levels results in cases remaining unsolved and serial criminals could remain free to commit additional crimes. The ISP’s inability to fill lost forensic positions has resulted in staff performing work outside of their official duties, which increases the backlog of forensic cases submitted to the labs.”

Meaning if the backlog persists, serial rapists can continue to terrorize communities, and single perpetrators can go unpunished. Scientists simply aren’t able to keep up with them.

Still, untested rape kits are only a fraction of the problem regarding sexual violence. Rape is still the most underreported crime in the United States. Perhaps because the criminal justice system doesn’t seem inclined to aid survivors or because the new president-elect has boasted about this very type of brutality.

“When it comes down to it, rape kits are not the end-all be-all of this issue. There are so many challenges with this kind of culture,” Benos said. “People advocate for different parts of the solution, and we’re advocating for this one.”

Header Illustration by: Rob Kelsey

NO COMMENT