Chicago Public Schools (CPS) is a news writer’s cash crop, a constant yield of breaking news stories dealing with everything from test scores to school closures and budget proposals. As a result, long-term problems – problems that only get worse over time – tend to be forgotten amid the fog of scandal that accompanies CPS.

The flaws with English Learner (EL) programs are those forgotten problems.

Non-native English speakers account for a large portion of CPS students. CPS schools are twice as likely to have EL students than the rest of state – 67,326 students, accounting for 17.5 percent of total enrollment. The issue with language transition among non-English speaking students is public perception of the necessary materials and faculty needed to foster a successful dual language program.

We tend to view EL programs as courses that teach English to non-English speakers, the way you might learn French in high school. But EL programs are anything but a simple language course. They are a completely different organism within the school system, requiring a whole departmental change in order to truly help a bilingual student transition into general education courses (taught in English).

“We make sure that they’re [students] supported emotionally and socially. Some kids are withdrawn; don’t even want to speak, let alone in their own native language because they’re ashamed,” said Kathy Trevino-Kniffin, the Bilingual Coordinator at Frank W. Reilly (PK-8) elementary school.

EL programs focus on teaching academic material and skills in a way that prepares bilingual students for applying those skills in an English setting. This means that a student must learn math in their language so they understand the material first, then learn to translate their understanding into English. This helps preserve the student’s native language and perpetuates a better understanding of English through skill-based comprehension rather than memorization.

“Changing that culture [learning environment] to ‘No you’re a value, you’re an asset, we want you here, we want to help you, please use your language, talk to others in your language, help teach us your language’ is what we go for,” said Trevino-Kniffin.

The Overview

To understand the problem with EL programs, we must begin with elementary school and middle school students – the protagonists of this story.

A student from a non-English speaking household enters the Chicago Public School system. The student can either enroll in one of the 11 (four more added in 2017) schools that offer Dual Language Programs, or enroll into a more widely available transitional school that offers English Learner programs.

Dual-Language programs are additive programs, meaning they maintain a heavy focus on native language in a collaborative environment. Non-English speakers are placed into their own classrooms from preschool to fifth grade, where curriculums are taught at first in an 80-20 fashion, the majority in native language with the minority in English. As the student reaches the transitional grade – fifth grade – students are placed in classes with a 50-50 split – half in English and half in the student’s native language.

“I personally believe in the dual language program because maintains their native language, and you want that, especially if their foundational skills were taught in their native language,” said Emily Mendez, Dual Language Coordinator at Carl Von Linne Elementary School.

“As they progress in grade every year, it complements the English part of their day and those skills are transferable.”

If a student chooses a transitional school, that student is enrolled in bilingual courses from first to third grade. Upon reaching third grade, that student is then mixed into general education classrooms taught in English with English Second Language (ESL) support.

CPS requires a minimum of three years of bilingual education for all English learner students.

Both choices require a substantial allocation of funds by the school and accountability on part of the faculty and administration to ensure that instructors and leaders are properly certified to foster successful programs.

“It has to do a lot with the buy in, you have to have an administration that wants it, that believes in it. You need staff that wants it and believes in it. You need to have families that want it,” said Mendez.

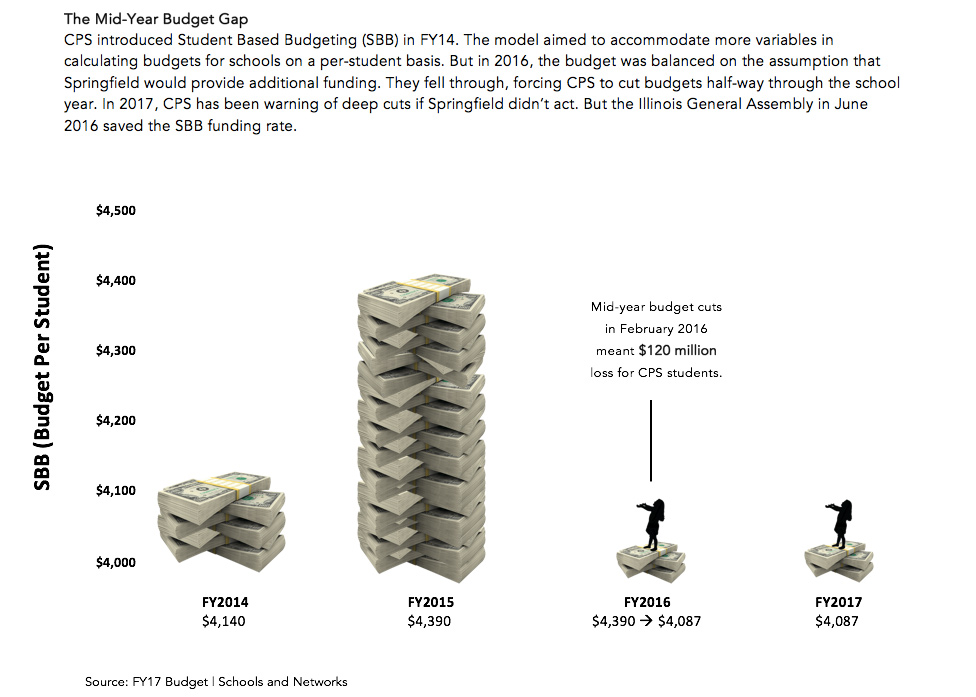

The Budget

Student Based Budgeting (SBB) determines how much money a school receives for core instruction based on the number of students. More money can be acquired based on different variables – grade, learning category, average family income level, etc. These variables are weighed differently. For instance, high school students receive a greater weight (more money per student) because they require more resources than middle school and elementary school students.

At the beginning of 2016, the base (SBB) rate was $4,390. The announced base rate for 2017 is $4,087, illustrating the announced reduction in annualized SBB funding by about $120 million.

See, CPS budgets are like those old suitcases you refuse to get rid of. As the years go on and you buy more clothes, larger clothes, the suitcase appears less and less accommodating. Eventually, the suitcase no longer supports the quantity of clothes it once used to, and as a result, a bargaining process begins. The traveler begins trading off clothes, such as removing a pair of socks to make room for an extra shirt. Bilingual programs are that pair of socks.

32nd Ward Alderman Scott Waguespack has called forth a resolution with the aid of students in his ward to hold CPS accountable in funding EL programs.

“We want a clear breakdown of bilingual funding by school so we can get a picture of what’s going on, if CPS is funding some schools more than others,” said Waguespeck. “The resources have to be equal or better for each one of these kids, and right now they are substandard or barely sufficient.”

Graphic by Aiden Kent

The Materials and Faculty

At the base of every successful EL School is a bilingual coordinator – the unsung heroes of bilingual programs. Good candidates are hard to come by, either due to lack of experience or lack of funding.

“From my understanding, this school didn’t have a bilingual coordinator last year and if I don’t say so myself, you need a strong ELPT [English Language Performance Test] Bilingual coordinator,” said Trevino-Kniffin.

Before Trevino-Kniffin’s arrival, Frank W. Reilly was a level-two school, categorized as “provisional support.” Her appearance was one of the strong factors leading to Reilly Elementary’s recent success as a top level-one EL School. The same can be said for Mendez at Linne Elementary, another top ranked EL school.

EL programs servicing non-English speakers also require separate classrooms accompanied with teachers holding ESL and Bilingual certifications. New teachers mean new salaries must be paid out. More necessity for room means allocating students to accommodate more space, typically resulting in larger class sizes.

“You can always use more teachers. I mean 34 kids in one classroom, you can split that in half. Ideal, heaven, would be 20 [per classroom],” said Mendez.

With schools’ budgets decreasing as the CPS financial crisis continues, most Dual Language schools have no choice but to accommodate through stacking teacher positions, or spending more time on a group-based instructional method rather than individualized help.

“You’ll have kids that are being pulled out of class to help other students in their native language. Sometimes they’ll spend time after schools helping them with aspects outside of schooling such as translating documentation and papers,” said Waguespack.

Curriculums taught in bilingual settings require materials such as books written in the native language of the student and in English. As Mendez described that sometimes the problem with acquiring these books goes beyond budgeting. When Common Core was passed throughout the nation, publishers weren’t able to publish new books fast enough to meet the demands of schools nationwide. In schools like Linne Elementary, teachers had to pull materials from outside sources in order to manufacture their own makeshift Common Core curriculum.

Testing

In order to properly measure a bilingual student’s progress, the student must take state tests – the NWEA/MAP (in the process of being transitioned to the PAARC) and the ACCESS test. In the conversation of measuring a school’s quality of education, the tests present concrete data that can be used by the school administration and teachers to see where their students need improvements and where they are performing well.

The ACCESS assessment is administered to bilingual students to track their progress in learning English. There are two standards set for the assessment. The Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) states that any student with a 5.0 cumulative score (ranked from 1.0 to 6.0) on the ACCESS no longer requires any state-mandated EL services and are deemed proficient in English.

CPS states that students who score below a 3.5 on their ACCESS assessment can opt-out of taking MAP tests and are not included into a school’s School Quality Rating Policy (SQRP) rating as a result. A score above a 3.5 requires that EL students take the NWEA assessment and be included in the SQRP rating. Schools want more of their students’ test scores counting towards their SQRP because it creates a bigger pool from which an average cumulative score can be derived from.

The Problem

When a student tests out of EL services in a school lacking the proper resources, two things can occur.

The first deals with the qualification of teachers. When a school can only hire three certified bilingual teachers, it makes sense to allocate them to bilingual courses, keeping the non-ESL teachers in general education classrooms.

“We’re lucky here at Reilly because we continue to place students in classrooms with certified ESL and bilingual teachers where other schools might not have those resources,” said Trevino-Kniffin.

When EL students transition into general education courses and are placed with teachers not ESL-certified, continued growth is hindered. Although a student tested out, that student generally still requires assistance from a teacher, which is difficult to accommodate when the teacher is not certified to translate.

The second deals with testing itself. In promotional grades, students must meet certain criteria in order to move onto the next grade. Those grades are third grade, sixth grade and eighth grade.

EL students are required to earn at least a C on their final report card and a meet the attendance criteria of no more than nine unexcused absences. Students no longer requiring EL services must also score in at least the twenty-fourth percentile of the state assessments.

“Teachers have that mentality where they think that since the test is English, they’re really going to push this English because these tests are in English and my students will do better on tests,” said Trevino-Kniffin.

You may have a bilingual teacher in a general education class, but that teacher will maintain a strong English presence for the sake of test scores.

“We still have families that don’t want the dual language because they want their kids to learn English and do well on tests,” said Mendez.

CPS and EL schools must work in sync with one another to ensure that both do their equal parts in ensuring the best education for each student. The schools that tend to fare more prominently in school ratings and testing tend to be those with strong leadership and necessary resources.

“Anybody can be a teacher, but a teacher can look at 20 kids and say ‘boom I know what I can help you with’ and group kids that complement each other, whereas somebody can teach a group but can you differentiate within a group,” said Trevino-Kniffin. “You can have 20 kids in front of you and have five different learning styles and not even recognize it.”

NO COMMENT