The evidence of DePaul University as the largest Catholic school in the country is not outwardly apparent – if you don’t count the 100-foot-high mural of St. Vincent silently smiling at the soccer field from the wall of Corcoran Hall. Even walking into the Student Center, its Catholic Campus Ministries office is a small space just to the right of the doors, no opulence here.

This low-key presence speaks to the unique approach to spirituality and diversity as DePaul’s main identity. On campus, there are about a dozen different religious and spiritual groups, all of different backgrounds, all with their own space provided. From Buddhist meditation to Jewish Life’s monthly Shabbat celebration, most of the mainstream traditions are accounted for.

DePaul also tends to be a hotbed of political debate. With the underlying message that the university tries to instill in its students of being compelled to make a tangible difference in the world, Chaplain Thomas Judge sees it as an inevitability.

“To be very simple about it, I don’t think you can be at an institution like ours, that has a mission like ours, and not take politics and current events very seriously,” Judge said. “Our Catholic and Vincentian identities encourage us to be in the world, working together for the common good, asking what needs to be done.”

But what needs to be done? Therein lies the reason that some of the protests and political statements have caused friction and divide on campus. During the last election as well as after, the feelings of unease, distrust and betrayal are evident. So how do the spiritual communities at DePaul handle the division?

“From a spiritual perspective, we’re trying to open up dialogue, we’re trying to open up prayer, we’re trying to help students understand that these things really do matter,” Chaplain Diane Dardon said. “I think dialogue is a spiritual act, especially in times like this.”

Spiritual dialogue is something former Interfaith Scholar Joel Gitskin is intimately familiar with. A formerly non-religious student, after freshman year he found Jewish Life and not only found his connection to the faith, but took on the role as the Jewish representative in a group composed of students specifically chosen to represent each religious group on campus in an attempt to promote interfaith unity.

“It was my junior year, so around 2014 to 2015,” Gitskin said. “We had some events that we organized every quarter, and then we’d also meet once a week. We usually brought in a quote from St. Vincent, and then we’d also bring some sort of prayer from our religious tradition that we really connected to and we’d talk about it.”

It sounds like the beginning of a bad joke: a Christian, a Jew, a Muslim and a Buddhist all walk into a room… Surprisingly enough, it ended up being quite a cohesive mix.

“It was very awkward in the beginning, because we all felt like ‘I don’t want to offend anybody,’” Gitskin said. “As the year went on, we just realized that we were all kind of the same, just wore different religious garb at different times, so we became close friends.”

Even when hot topics and political opinions came up, the discussions were always civil and open to differences.

“It was interesting how much we were all on the same page when it came to basic morality, which is what a lot of the current events we’d talk about boiled down to,” Gitskin said. “We don’t want anyone to die, we don’t want anyone to be treated as lesser, and that’s because of our religion and the way we see the world.”

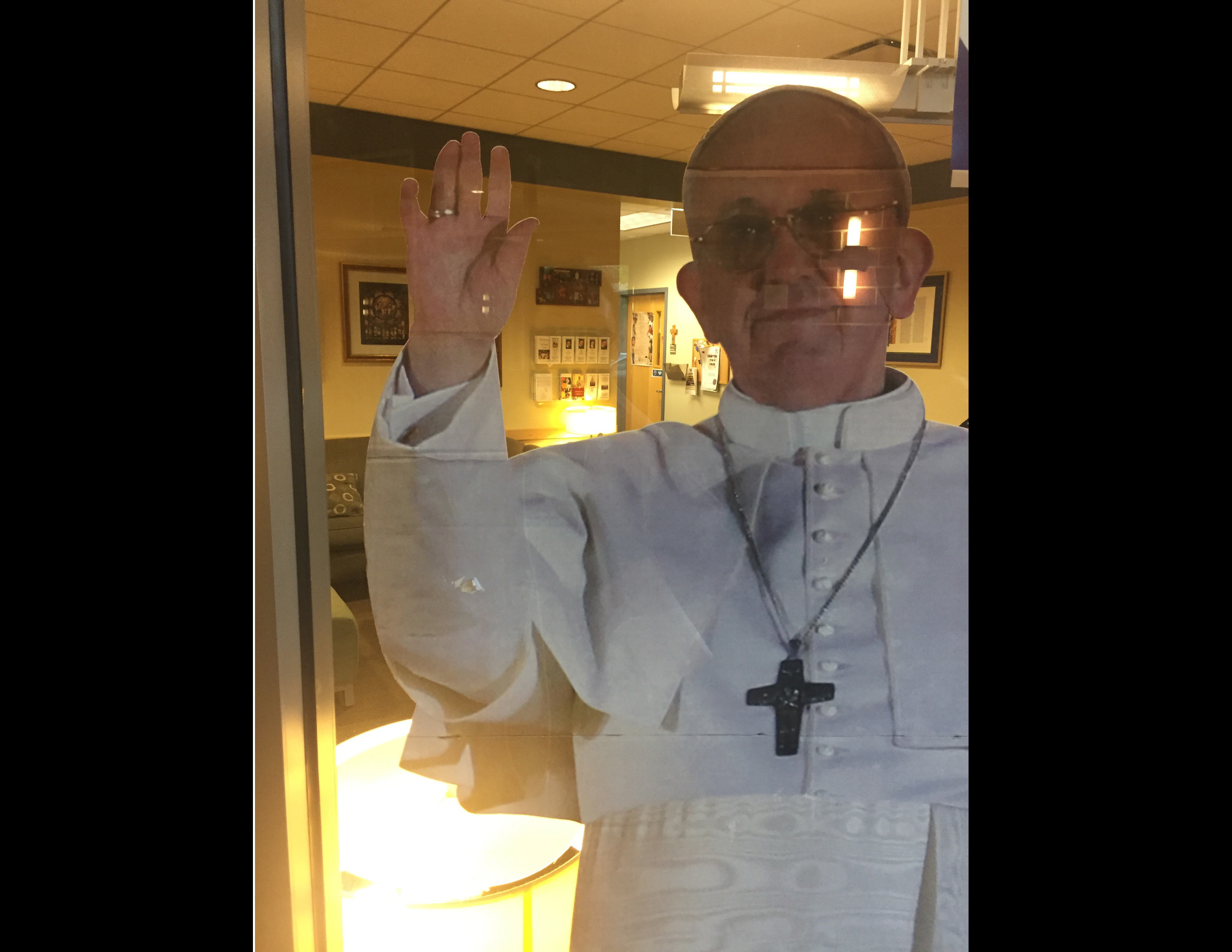

Downstairs, in another religious space announcing its affiliation via the large cardboard cutout of the pope grinning at students in the window, Catholic Campus Ministries student officer Ben Gartland sits eagerly in an office loaned for the interview, somehow looking eager and bright-eyed on an early morning. The passion he cultivates for his faith asserts itself in his various duties for the organization.

“I help lead the team that runs the Sunday night mass, I supervise three student leader assistants, I supervise the liturgical choir assistant, and I’m also on the pastoral council, and we’re a student leadership team of Catholic Campus Ministry,” Gartland said. “We talk about ways for outreach to try to get people into CCM, about culture and climate here in the office, and building our own leadership skills.”

Unlike Gitskin, Gartland had an immersion in his faith from the beginning, and became involved in various Catholic groups before stepping foot on campus.

“I was raised Catholic, so I was going to church every Sunday, I went to Catholic school from first through twelfth grade,” Gartland said. “I started to get fairly involved in high school in terms of spirituality. I started going to my parish’s youth group, and went to a couple of conferences. I’ve been heavily involved my whole life, really.”

Ironically, Gartland didn’t even know when he chose DePaul that he was about to continue his tradition of Catholic school at the largest Catholic university in America.

“I have this wonderful scholarship opportunity – my dad is a professor at a Catholic university in Kansas City called Rockhurst, so there’s competitive scholarships available for kids of faculty between Catholic schools,” Gartland said. “I didn’t know a lot about DePaul before, I didn’t know it was the largest Catholic school in the nation, I didn’t really know what Vincentianism was.”

In his time at DePaul, Gartland notes the effort to increase an open environment by the Catholic Campus Ministry space, not only to Catholics but for the student population in general.

“It’s a very vibrant community,” Gartland said. “There’s always people here, there’s always people talking. We have this big open lounge here, so we try to make that an open space for as many people as possible, Catholic or not.”

Part of creating that open space is making sure to connect to other faith groups. It’s hard to do that, however, when your own group is dwindling, which seems to be happening to the entirety of Student Affairs.

“I think, you know, enrollment is down in general,” Gartland said. “And it’s interesting to see, the parish, which is independent of the university, they’re having problems with people not showing up to mass every week. One of the things that we’ve talked about, there’s this atmosphere where people just feel tired, you know? It’s been a rough year both on campus and nationwide, and it just seems like everyone’s tired.”

Certainly the 2016 election has appeared to have a lasting psychological effect on the general population, and it’s been observable for months. A Pew Research study from October 2016 reported that six in ten Americans felt exhausted by the election coverage as early as July. Combined with the final results, which left many reeling in shock, and the seemingly constant political drama that’s continued to dominate headlines, and it’s no wonder most students just want to go home and curl up under the covers. Gartland’s trying to create an environment that’s a reprieve from the current news cycle.

“We’ve got this retreat coming up that’s focused on, you know, this is a relaxing retreat,” Gartland said. “It’s something to try and get your mind off the stress of school and everything that’s going on. We’ll see if that ends up being successful. I think what we’re trying to do is open up the space as something that’s very welcoming to people who really just need a break, who just need somewhere to go.”

Pope Francis cutout in the window of the Catholic Campus Ministries (Rachel Dick, 14 East Magazine)

Cozy, neutral-toned clothes and a soft, motherly voice are the first things one notices about Protestant Chaplain Diane Dardon. Easy to laugh and with a gentle stare that suggests a nonjudgmental, curious ear, Dardon describes her job as “shepherding” the broad Christian community at DePaul.

“It means opening my office for pastoral care, for students who need a pastoral voice in the middle of some struggles, I do a ton of that,” Dardon said. “I do studies, lots of speaking, and then I work with our student religious organizations on campus, not just the Christian ones. So it’s a busy life.”

Caring for students in the midst of conflict appears to be quite a theme in Dardon’s professional history. In pastoral positions at both University of Northern Iowa and Northern Illinois University, Dardon encountered events that rocked the campuses.

“When I was at UNI, it was at the time when the Twin Towers went down, so we were in the middle of another big political thing,” Dardon said. “When I was at NIU, I had worked there only a few months, we had a mass murder shooting on campus, another high-tension time.”

From her experiences, Dardon developed a vision for how to mend political strife that drives her work at DePaul.

“I’m more and more convinced that if we do not open up more conversations and look at the importance of all voices – if we don’t break down this sense that my way is the only way – I feel like we will get nowhere,” Dardon said. “And one of the things I have to say to the interfaith groups when they’re talking about, ‘I can’t possibly understand how someone could believe this,’ I say, you know, your scripture, whatever tradition you’re from, it indicates that there is diversity in the world.”

Diversity in the world, and diversity even within the campus religious groups. Various factions of Christianity are present within DePaul, and for many years, according to Dardon, a high level of rancor existed between groups, a level of competitiveness that in her time at the university she’s hoped to mend.

“Immediately my response, as a person of faith, I am quite certain that there’s enough Jesus to go around for everybody,” Dardon said. “I’m quite certain this is not what God intended for the kingdom, that we’d all be sitting around and saying, ‘He’s mine, my way is the right way.’ It’s just been in the last 18 months that I have seen some movements by students who are coming to me and reflecting back.”

Currently, Dardon is working on putting together student leaders from every Christian denomination for a full day retreat dealing with disunity within the Christian community. If the leaders are ready to make a change, Dardon figures, they will be able to spread the message into the world. It’s something of a theme with Dardon, encouraging students to take charge and actively work toward the changes they want to see. In the current political climate, it’s been how she handles many of the visitors looking for guidance.

“I have not really encouraged students to necessarily get involved politically, because I believe everybody knows how they can make a difference,” Dardon said. “What I’ve been saying to students – and I’ve had a very, very busy office the last few months – when students are coming in, they’re so distraught. It’s because of helplessness and hopelessness, that sense of ‘I can’t do anything,’ and once they recognize that that’s why we’re really talking, then I try to lead them into something, a way of understanding.”

For Dardon, her way of making a difference might seem small, but she’s hoping to use it to spread a sense of community on campus.

“I’m really trying to be – you know, I’m trying to set aside any of the saltiness that comes from watching what’s going on in the world and just be more genuinely kind,” Dardon said. “So as a result of that, the Office of Religious Diversity once a week has a table down in the atrium, and we’re doing acts of loving kindness. We’re giving people a quote and a little treat, and then on the back of the quote card there’s a suggested act of kindness. Because doing something kind is doing something.”

University Ministry offices (Rachel Dick, 14 East Magazine)

Martin Luther King Jr. silently watches over Chaplain Keith Baltimore’s office. The entire room is small and tightly packed, but filled with rich, warm tones and a soft light that suggests coziness rather than compactness. There is also a red poster with the word “Sankofa” in gold lettering, advertising the program that Baltimore put together five years ago for African-American students who want to focus on leadership a.

“It’s a year-round program, and we have a series of retreats in the fall, winter and spring quarters,” Baltimore said. “For those, we take students off campus for the weekend, and we dive into very tense subjects, such as sexuality, relationships, love. And mental health, that’s a huge issue for us also, that we help students to develop and grow in it. And then our leadership retreat in the spring focuses on dealing with a lot of the -isms: racism, bigotry, cultural development, and levels of resiliency.”

Though Baltimore works with students of all races, ethnicities, and backgrounds, his primary focus is on the African American community at DePaul. Being chaplain and program coordinator for the Office of Religious Diversity, Baltimore not only advises the largest cluster of African American student groups at DePaul, but creates programming and events for the office and does traditional spiritual guidance. However, surprisingly, his favorite part of the work is that a lot of it has nothing to do with beliefs.

“It’s not always religious or spiritual, in fact, a lot of people don’t realize that the majority of the things that we do don’t have a spiritual or religious category,” Baltimore said. “That’s why I say it has a spiritual or religious component, not religious events. These aren’t things you’d see in a Christian church.”

Baltimore didn’t envision himself as going into clerical work at first, and originally pursued a career in politics. After a couple of years, he decided that it challenged him ethically too much to continue, and came to DePaul with an interest in working in a higher education environment.

“I was and am still interested in working at DePaul as faculty,” Baltimore said. “But this opportunity just came along the way, and it’s incredibly fun.”

Fun as it can be, Baltimore, like everyone in the Office of Religious Diversity, faces the challenge of guiding his students through a world that has appeared to change incredibly rapidly. Like the others, he talks about high levels of anxiety, and a sense of betrayal toward people who may have voted a certain way. While he compares it to the aftermath of a visit by Breitbart writer and controversial personality Milo Yiannopoulos in spring of 2016 that resulted in protests that interrupted Yiannopoulos’ presentation, Baltimore says the attitudes have a very distinct and important difference.

“I noticed then that I saw African American students feeling unsafe on campus,” Baltimore said. “And so you would see large clusters of African American students banding together, and as a person who works with African Americans, you’d think it would make me feel good, but it didn’t, because they were saying, we need to protect ourselves, and the only way we can do it is to kind of close ranks. It’s happening again, but this time it has a different spin. I feel that there’s a kind of positive mobilization. So I sense now folks coming together.”

In a time that has invited attitudes of nihilism and pessimism, where the focus for many groups has turned to sheer survival, Baltimore is hoping to preserve the type of long-term hope that enables people to envision a future. However, he laments, that kind of attitude isn’t always accessible to people in marginalized communities. So how to shift the focus to a larger scale?

“Our programming is about helping people to heal, it’s not just a desperate survival of reactionary tactics to what’s going on,” Baltimore said. “It’s not always healthy to be calling EMS because you’re gushing blood. At some point, the blood’s got to stop, you’ve got to start healing. To save something for the future, you have to trust in the future, you have to believe there is one. And so that’s the value of spirituality and faith, which is trying to say, yeah, I think I will set aside something for the future, because I believe there is something worth it and valuable about the future. In our community, we gravitate toward conversations about God, which helps them to think about the future and the larger scale of their life.”

Though most of DePaul’s religious organizations are centralized in Lincoln Park, the Loop campus holds small offices for the school’s spirituality workers as well. Seamlessly integrated into the hustling academic space, there’s little to suggest Chaplain Thomas Judge’s cozy little enclave, cleverly situated right next to the cafeteria, has anything to do with Christianity and spiritual counseling. Judge speaks softly, and pauses often, choosing every word with the utmost care. Softball or hardball questions, he considers both with the same weight.

Judge has a bit of a different crowd to serve than most of the others in the Office of Religious Diversity. His work is geared toward the adult students, the law students, and business school students who center their education downtown. But working with students in general is his passion.

“I just paid attention to myself, and I knew that I liked higher education, that I really loved people and getting to know them and maybe trying to help them, and I was really interested in the deepest, what I consider to be the deepest questions in life,” Judge said. “It took me years to figure it out, but all of it made me realize that I wanted to get into ministry, and doing it at a university was a good fit for me.”

Coming from Loyola, another college rooted in the Catholic faith, Judge observes many differences in the way their specific approaches influence their missions.

“Loyola is a Jesuit school, DePaul is a Vincentian School,” Judge said. “To many, there’s not much of a difference. But perhaps to people who know something about both, there is. The Jesuits are very intellectual. They’re zealous about their work in higher education in Chicago and around the world, and in some ways, they’re one of the more elite communities of higher education. The Vincentians are just as committed to their educational mission, but they are also very pragmatic, rounded in the real world, and committed to working with the poor.”

As to whether this plays a role in the high political involvement on campus, Judge says: definitely. DePaul’s mission to get students involved in the community through service, Judge says, encourages an awareness and passion that might otherwise not surface. However, he says, it is important to supplement activism with a self-care regimen.

“Being in touch with my faith helps me, nurturing my relationship with God, and asking God to be with me,” Judge said. “I think He makes his presence very real to me through my family, friends, and colleagues, so I try to reach out to them. I try to do things I enjoy: working out, doing community service, reading good books.”

Judge also reiterated Baltimore’s advocacy of faith, and trust in a future with a positive outcome.

“Now, today, as we experience a lot of political discord, a change in presidential administrations that has resulted in some being fearful of their future, because of those things, people begin to lose hope,” Judge said. “And so I’m trying to be present, to encourage them to know that they’re wanted and loved, and that together we can resist these voices that are maybe less kind.”

Header image by Rachel Dick

Correction: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly labeled a cutout of Pope Francis as St. Vincent de Paul. We regret this oversight.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST