It was springtime in Chicago, and the city was burning. It shuddered and gasped in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination on April 4, 1968. Riots on the West and South Side decimated entire blocks, and the glow from the fires could be seen from the Gold Coast neighborhood – over five miles away.

West Madison Street was deserted. Loose bricks were scattered across the pavement, and a sea of broken glass flashed orange under a few streetlights. The road ahead was empty – with the notable exception of the military checkpoint that Joseph Link and Martin Lowery were rumbling towards in a rust red station wagon.

Over 3,000 members of the National Guard had been deployed to the city before the weekend was over. Another 2,000 in the suburbs were on high alert. Lyndon B. Johnson sent the Army’s 5th infantry division to O’Hare Airport at the request of Mayor Richard J. Daley, who believed his city was on the edge of insurrection. The mayor infamously ordered his boots on the ground to “shoot to kill” the arsonists and “shoot to maim” the looters they saw. By Sunday morning, he had put a 7 p.m. curfew in place for everyone under the age of 21.

Link cranked his window down as he rolled up to the checkpoint. A soldier in full uniform looked him and Lowery over – a couple of cleancut kids in sweaters and slacks – and asked them a few questions. They answered politely, sitting up a little straighter and speaking slightly deeper than normal. Of course they were 21 and of course they were on their way home.

The soldier could probably tell they were lying, but he waved them through. He’d heard the reports of snipers shooting at (and hitting) cops the previous week, and he didn’t want to be out in the open any longer than he had to. Link thanked him and pulled through, cranking the window back up and wincing at the crunch of glass under the tires. It wasn’t his car – he was borrowing it from Thom O’Connor, and he didn’t exactly have the money to buy new tires.

As soon as the window was sealed, Lowery let himself breathe before he turned back to gingerly open the manila folder on the seat behind him. He smiled. It looked good. The galleys were ruler-straight, the ink was fresh and the pictures were clear. Link was white-knuckling the steering wheel – for good reason – but Lowery let himself chuckle. It looked like The Aletheia was getting published this week after all.

I. The Banquet

On the top floor of DePaul University’s Student Center, thick-framed photographs cover the walls of a wide, beige elevator lobby. Each is blown up, some nearly to life-size, and weave a rough tapestry of DePaul history. One that always caught my eye is the Nun Playing Soccer: a white habit flying across the field and a student defender whose stance suggests either a fear of being run over, of God, or some confused mix of both. The photograph I missed – until recently – is on the other side of the room.

Chicago students protest in solidarity with the DePaul Cram-in (image courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collections)

It’s nondescript and monotone. You can tell they’re protesters, at least. They’re in suits – which is sort of weird – and it looks like they’re in the Loop. But their signs offer more questions than answers: a faint imperative to “Save the STUDENT VOICE” from the back, something about student publications in the middle of the crowd. There’s even some representation from Loyola University on the far left expressing solidarity with the “DePaul Cram-In.”

The Cram-In went something like this: In 1967, on a sunny afternoon in May, Father T.J. Wangler made his daily commute downtown to the Lewis Center. At the time, he was DePaul’s vice president of student affairs – one of the highest-ranking administrators at the university. In the warm stone-tiled lobby, he stepped into an elevator and pressed the button for the sixth floor as the doors closed behind him. Then, once they’d opened, he tried walking into his office. He couldn’t.

The small hallway leading into it was blocked wall-to-wall by a dozen or so student journalists sitting cross-legged on the floor, pretending to study for finals.

That year, DePaul University’s official student newspaper – The DePaulia – had a staff around forty-strong. The paper was dynamic and bold, covering abortion, questioning the newly installed quarter system and, at times, criticizing the school’s administration.

On May 20, 1967, the university hosted the Publications’ Banquet inside the Edgewater Beach Hotel for both The DePaulia and DePaulian – the school’s now defunct yearbook. At the banquet, members of the faculty and administration recognized campus writers and announced next year’s editorial leadership. As the yearbook wryly noted the following year,

Sometimes a leader is appointed and sometimes a goat. The forced smiles and languid handshakes are everywhere. The retiring editors are given the chance to reflect, for last year the smiles and handshakes were theirs. Yet how many of them proved meaningful when the chips were down and the going rough? For the new editors, vague promises and those same smiles and handshakes.

At the 1967 banquet, faculty advisor Marilyn Moats Kennedy announced the DePaulia’s next editor-in-chief: a sophomore by the name of Mike Walters. The staff quit. Each member handed a letter of resignation to Kennedy before walking out the door.

1966 had been Kennedy’s first year with The DePaulia. Twenty-three and fresh out of Northwestern, she wasn’t much older than the staff, and their relationship was a rocky one. For one, she stayed clear of the office. According to the ex-staff, Father Wangler advised her to keep her distance in order to avoid the possibility of any “indirect censorship” from faculty supervision.

“The immediate misinterpretation by Mrs. Kennedy,” one ex-staff member later wrote, “was that ‘avoiding the office’ was tantamount to ‘ignoring the staff.’”

In the weeks leading up to the banquet, they claimed Kennedy had kept the name of the new editor-in-chief in a sealed envelope – “sort of like a Miss America contest.”

Publications’ Banquet, 1968 DePaulian (courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collections)

Then, in May, she made the announcement. The outgoing editors had recommended Mary Jeanne Klasen, a junior and the paper’s managing editor. But Kennedy had picked Mike Walters.

It’s hard to say why exactly Kennedy picked a 19-year-old to lead The DePaulia. Ernie Kopczynski– one of the graduating editors – told the University of Michigan’s daily paper that Kennedy had cited Walters’ “ability to write, journalistic potential, and future plans for the paper” when she announced his appointment.

It’s not hard to see why the staff objected. Walters was a sophomore whose name didn’t appear in the paper until five months before the banquet. They claimed he’d written a total of eight articles for the paper, on top of having no idea how to set type or prepare the articles for publication – an intense technical process before anyone had bothered to invent a digital word processor.

Whatever the criteria Kennedy used, seniority and experience didn’t seem to top the list. James Krokar – a professor emeritus of history at DePaul today – attended the university in the late 1960s. He remembers choosing the school in part after seeing a copy of The DePaulia on a newsstand. A story on the front page was criticizing the administration, and the paper’s outspokenness stuck with him. He enrolled soon after.

By the time he was on the staff, Krokar remembers The DePaulia as a paper unafraid to stir the pot. In 1962, a front-page editorial had challenged the administration to do more for black students, urging them to “take action [to] overcome the many racial barriers that exist.” In 1964, they openly mocked a construction project after the school made a show of tearing down some railings by the Science building: “What a monument to scientific endeavor!” an anonymous writer rejoiced.

At one point or another, The DePaulia may have crossed a line. By the time Kennedy arrived as advisor, the administration seemed to be itching for a more sedate student voice, according to Krokar and other alumni.

In 1967, two people had the power to appoint The DePaulia’s editor-in-chief: Kennedy and Father Wangler. It seemed all they had to do was agree, and they agreed on Mike Walters, and by the end of the Publications’ Banquet, he was left with a staff of none.

The ex-staff did not go quietly. A few of The DePaulia’s graduating seniors met with Father Wangler the following Monday, asking him to form an Ad Hoc committee – made up of three uninvolved students, three faculty members and an administration official – to formally investigate Walters’ qualifications as an editor. But the resigned staff also issued a memo: “The proposals we have made are in no way an attack upon Walters or Mrs. Kennedy,” they wrote. Wangler declined the offer.

A few days later, he found a newsroom in between him and his office: the DePaul Cram-In.

“We were very angry at the time, very agitated,” Joseph Link recalled. “The administration, and especially Father Wangler, was the enemy in a sense. But looking back, from my perspective now, my personal feeling is that they were very tolerant of us. They could have had us thrown out! And they didn’t.”

Student coverage of the DePaul Cram-in (courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collections)

Father John Cortelyou – DePaul’s president at the time – didn’t seem particularly bothered. “They can stay until doomsday if they’re orderly and quiet,” he said to a student reporter from The Michigan Daily.

The protest didn’t confine itself to the Lewis Center for long.

“We were very clever,” Martin Lowery told me. Just as the sit-in began, he placed a few calls. The next day, the Chicago Daily News showed up to cover the sit-in. Then, a few Chicago TV stations followed their lead. Lowery remembered student protests popping up “across the city” on their behalf – from Lincoln Park to the Loop with students from Loyola University and beyond.

The students in the Lewis Center hallway held their ground for three days and two nights, sleeping in bursts against the wall or curled up on the worn-thin carpet. At the end of the third day, Wangler caved. An investigation was launched.

Nothing happened. By the end of the summer, each segment of the committee had submitted a statement: one from the students, the faculty members and the administrator. They all declined to challenge Walters’ appointment and his qualifications.

On a cool summer afternoon in August, after they heard the news, a handful of ex-staffers trudged to O’Connor’s Lincoln Park apartment. He lived at the intersection of Dickens and Dayton. They slouched down the stairs to the basement, silent except for the creaking of wood. They sat for a while. It had been a long summer of waiting and sweating, and they were exhausted by the anticlimax. Then – and nobody could remember exactly when – they started to talk.

“There were a group of about six of us, licking our wounds,” Lowery remembered. “And there was a group decision. We said, ‘We’re going to start our own newspaper.’ And I remember the moment. It was a very heady moment.”

They decided they’d call it The Aletheia.

II. The Student Voice

The word “aletheia” translates roughly to “truth” in ancient Greek. In the 20th century, the philosopher Martin Heidegger resurrected the term to invoke a sense of absolute honesty and disclosure. It was extreme and pure, in an abstract sort of way.

“It was a little bit ironic, considering what we’re facing today,” Lowery said over the phone. “It was a hubris idea, that, you know, ‘We’re going to speak the truth.’ A little bit pretentious, I would say.”

After I processed that, I had to interrupt him.

“You’re saying the name was… a joke?”

He laughed. “There was a bit of irony,” he said. “There was always that sense of – a little bit of Stephen Colbert. Most definitely.” Before he graduated, Lowery would become the publication’s editor-in-chief.

The Aletheia would be free. It would be independent – financially, editorially, logistically and spiritually. It would be the unchained student voice, free from the long arm of DePaul’s bureaucratic complex. The only trick was making it happen.

Mike Eichberger – 1968 DePaulian Yearbook (courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collections)

Advertising has been the lifeblood of journalism for decades, and a student paper starting from scratch would be no exception. At some point that summer, it occurred to the group that it would take more than donations from sympathetic faculty members to get The Aletheia off the ground. That’s where Mike Eichberger came in. A childhood friend of Lowery’s, Eichberger was never a part of The DePaulia himself. He volunteered to sell advertisements for the upstart paper, even though no one was quite sure what that would entail.

Link, who would eventually become the paper’s managing editor, remembers one evening sitting in the apartment at Dickens and Dayton. A table in the middle of the room was covered with paper – some future Aletheia stories – and the group was beginning to lose hope. Eichberger had been gone for hours, trying to sell something to someone. Then, he burst through the door.

“I SOLD ADS!” he yelled, laughing. He was waving something around in his hand – money, receipts, maybe just paper scraps for the sake of dramatics – it didn’t matter. For the first time, the group realized they were onto something. They had something.

The Aletheia’s staff formed a non-profit company: the Dickens & Dayton Publishing Corporation, mailing address 849 West Dickens. Less than 40 days later, on Sept. 28, 1967, they printed their first issue.

They started out printing with Campus Press – the same organization that printed The DePaulia. The Campus Press handled a lot of the technical aspects of publication, like stitching together the stories, developing the masthead and headlines and – of course – printing the issues. They also happened to be expensive as hell.

So The Aletheia looked elsewhere. After their first few issues – published biweekly – they eventually discovered the Students for Democratic Society (SDS). They offered free printing at their headquarters on West Madison, several miles away from Lincoln Park. They were a little out of the way and weren’t great at making deadlines, according to the alumni familiar with the process, but they usually got the job done.

Since SDS could only print – not format or develop – they bought a Varityper typesetter. It was a marvel – a physical, shining word processor created decades before the world ever heard of Microsoft. It could align and italicize text, change font and more. They paid $509.25 for it – a value well over $3,000 today.

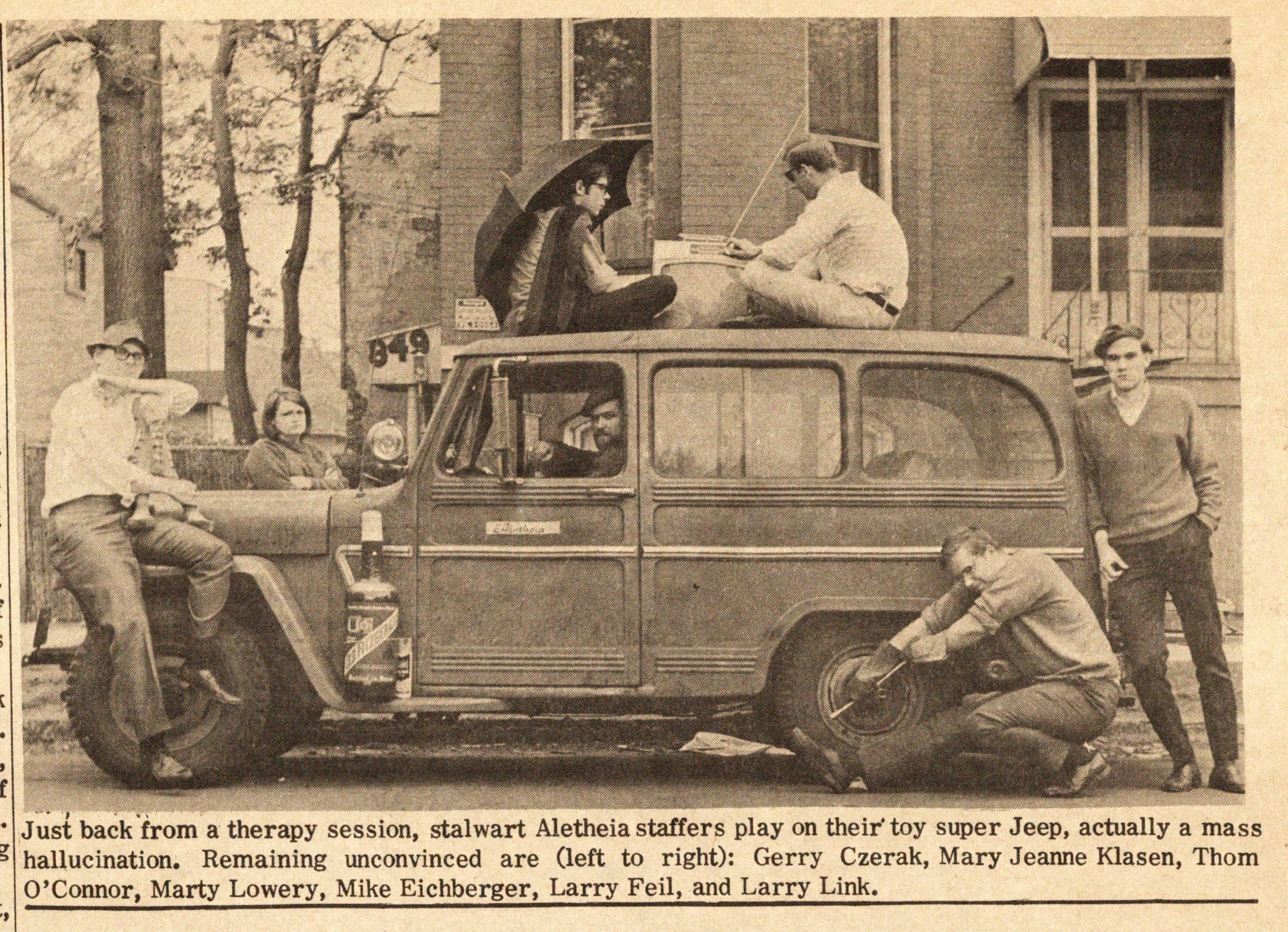

The staff of the Aletheia – 1969 DePaulian (image courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collections)

With its newfound freedom, The Aletheia tore into campus life, the administration and local politics in its first year of publication. It was pugnacious and relentless. According to an “informal content analysis” compiled by Joseph Link – something he put together completely unprompted after I first interviewed him – The Aletheia published a total of 67 stories on campus news by the end of their first year.

They often managed to scoop The DePaulia – which, to be fair, wasn’t altogether surprising, since the staff had been The DePaulia a year earlier. The competition didn’t go unnoticed. Bill Bike, writing for The DePaulia in 1978, admitted that after The Aletheia’s success and “a lapse of a few years in the early 1970s, The DePaulia began to concentrate on investigative journalism more than ever in the middle of the decade.”

All things considered and under the helm of Mike Walters, The DePaulia seemed to do just fine. After a year or two, The Aletheia’s staff and The DePaulia’s were even friendly. DePaul was a much smaller school back then; it would have been hard for them to avoid one another. Before he graduated, Walters started a breakfast program with a few friends that fed kids in Lincoln Park. More than a few of The Aletheia’s younger alumni remember meeting each other there. Walters could not be reached for comment.

It was just after midnight in the winter of 1968, and the Schmitt Academic Center (SAC) was quiet. On Kenmore Avenue, the only source of light was a street lamp down the block, which reflected a dull orange off the building’s glass doors. After a moment, a figure appeared. They checked their watch. Five minutes later, a few more had arrived. They waited. The watch was checked again. Then, from down the street, a final person crept into view. As they got closer, they nodded.

Empty.

A coat hanger appeared from inside a jacket, and one of the shadows hunched over the door. After a minute of scratching and a moment of vulgarity, click – the door swung open. They stepped in, popped on their flashlights and started down the hall. The building was theirs to roam.

In October, The Aletheia had published an editorial on campus security, claiming whatever DePaul had wasn’t enough. After three months and sensing little had changed, the staff decided to make its point a little more clearly.

Inside, the first floor was pitch black and the escalators dead still. The elevator doors had been locked for the night, so the raiding party swung around to the south stairwell. The beams of their flashlights cast deep shadows around the corners and on the stark concrete walls as they climbed – past the second floor (too many windows), past the third and fourth floor (too many alarms from the library), all the way up to the fifth floor. There, the doors were unlocked.

The Aletheia’s coverage of their own break-in, circa 1968 (courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collections)

The room opened up to a small sea of secretarial desks and typewriters – costly IBM Selectrics, no less. The group fanned out, wielding small slips of paper and Scotch tape. Every few desks, they tagged typewriters, staplers and chairs with a tight, typed message:

If we were burglars or vandals, we would have stolen or destroyed this valuable item.

They popped back down to the fourth floor through the escalator well into what was then part of DePaul’s library, taping every aisle. On the third floor (one coat hanger later), they used their final few slips on a priceless collection of Irish history books before hauling an “Irish Throne” – a chair over six feet tall and weighing a hundred pounds – down two flights of stairs to sit in the middle of the main floor. They were giggling at that point – their initial seriousness had dissolved into giddiness from the adrenaline and lack of sleep – and decided they’d done enough journalism for one day.

Around 2 a.m., a Chicago police cruiser rolled slowly down Kenmore Avenue past the SAC. If the lights inside had been on, the officers may have noticed the trespassers standing stock still ten yards from the street. They did not. As soon as the car was out of sight, the staffers dipped out of the building and scattered into the frigid night. Suddenly, they had a front-page story to write.

III. The Dragon Slayers

It’s difficult to appreciate how incredible – how traumatic – the 1960s were to the people who lived them.

Americans watched police brutalize nonviolent protesters across Alabama on the nightly news in 1965. They watched the sky above Los Angeles darken with smoke from the Watts Riots in 1966. By the end of the decade, tens of thousands of Americans had been killed in Vietnam. The world was watching when Chicago got rocked by the 1968 Democratic National Convention, featuring a legendary clash between anti-war protesters and the Chicago police. That night, a wave of sky blue helmets crashed on top of students with tear gas and nightsticks on national television, and millions of viewers were shocked to their core by the violence. America changed. So did The Aletheia.

The Aletheia began to call itself a “journal of issues.” It looked outside of Lincoln Park and Chicago. According to Link’s informal analysis, stories with a campus focus dropped from 1968 through 1970. Their first year featured nearly 70 stories about DePaul news. That dropped to 22 in their second year, and then only 10 in the third.

Thom O’Connor and Joseph Link work on an upcoming issue of the Aletheia (courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collections)

“It was just the times,” Link told me over the phone. “It was just so unsettled, and very difficult to find an outlet for that kind of protest.”

In a world long before you could express any angst in a Facebook monologue, The Aletheia filled a critical gap in the 1960s: self-expression. “I don’t think there were many print vehicles that captured that sense of energy and protest,” Link said.

Lynne Adrian attended Bradley University in central Illinois during the late 1960s, but a friend from high school – Kenneth Stikkers – went to DePaul. He worked as a staff writer for The Aletheia. After reading some of his coverage, Adrian wrote a letter to Stikkers asking if the paper would be interested in a downstate correspondent. When they said yes, she mailed back a few articles about the 1969 Vietnam War Moratorium. She captured the massive crowd that marched through the streets of Peoria, Illinois, showing DePaul students that their own anti-war sentiments weren’t an isolated phenomenon.

Today, Adrian is the department chair of the American Studies program at the University of Alabama. When I talked to her in March, she said that writing for The Aletheia was her first brush with activism, which she pursued as a second-wave feminist in the 1970s.

“It was the first way the political drive I was developing came out,” she said. As she watched the protesters and police clash outside the 1968 Democratic Convention on TV, she was “literally about to go down to the Loop and file paperwork for the demonstrators to get them out of jail and stuff.”

“My parents said ‘oh-hell-to-the-no,’ but I think in that sense it was reshaping – to be able to see that there were things you could do,” Adrian said.

But as the world turned, The Aletheia couldn’t keep up forever. Only one new writer joined the paper in the fall of 1970, three years after the founding. Recruitment had dried up. At the same time, in the wake of the Kent State Massacre, there was a sense among student activists that they’d hit a wall.

John Fitzgerald was an Aletheia staffer in the paper’s later years, and he remembered the beginning of the end for America’s counterculture. “When Nixon said the war was over and we started to pull troops out of Vietnam,” he said in a phone interview, “it was like a balloon, where all the air goes shhhhhh out of it.”

Martin Lowery works on an upcoming issue of The Aletheia (courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collections)

There was also the issue of money. Despite its early success with advertising sales and faculty support, the place was always run on a shoestring. While the staff was never paid, there were good months and bad months. It became harder and harder to pay the rent as interest dissipated.

The staff decided to suspend publication indefinitely following the Feb. 24, 1971, issue. In the final paper – issue number 42 – the editors filled the entire second page explaining why they’d decided to shut down production. Gerry Czerak, an executive editor at the time who had worked on The Aletheia almost from the day it began, had the first word.

“The reasons behind the decision are basically two,” he wrote. “The current staff has no more dragons to slay, and there appear to be no others who would like to inherit the role of editorial dragon slayer.”

Thomas Hartmann, another Aletheia alumnus, remembered the move-out. “The day they closed shop on us,” he told me, “either the landlord had taken a dislike to us or we weren’t paying our rent, but they let their dogs dirty up the place. We walked down there, and the stench of dog in there – it was pretty striking.”

“That was the end of the paper,” he said.

IV. The Alumni

As I interviewed more and more former members of The Aletheia, I noticed something remarkable: nearly every person had a copy or two of the paper in their possession. They’d managed to hold onto them for almost fifty years. Some of them sat in a box under the stairs – or in the attic, or in the crawlspace – for years, but they had them. Gerry Czerak thought he had every issue the paper had ever published, but he couldn’t be sure.When I spoke with him, he spent more than a few minutes digging through manila folders and shoving boxes around.

The Aletheia has stuck with a lot of people. Even Marilyn Moats Kennedy – the paper’s old “nemesis” who died in January 2017 – said she respected the publication in a farewell interview with The DePaulia, 10 years after The Aletheia was born.

“Those kids were talented,” she said. “They had a mission, and they were perceptive enough and had enough nerve to point out the bad things at DePaul.”

I asked alum Dr. Martin Lowery – now an executive with the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association – the last time he’d thought about The Aletheia. I expected the answer to be in months or years. He surprised me.

“I actually think about it all the time,” he said. “I’ve found it to be one of the greatest experiences of my life.”

“I can remember a time on the North Side – when the issues would arrive, people grabbed them up like it was the most important thing for them to be reading,” he said. “And it was a hugely formative experience for me, to see the power of the press.”

The Aletheia’s Third Annual Genghis Khan Awards, awarded to individuals responsible for “a significant contribution to the lack of progress civilization has made.” (courtesy of the DePaul Richardson Library Digital Collection)

Joseph Link, who went on to work at McGraw Hill for 30 years and Bloomberg News for eight, echoed that: “The way we looked at issues – the way we questioned things – always stuck with me,” he said. “I believe that throughout the rest of my career, the experiences I had from The Aletheia helped me question things around me, in my own workplace and life. That inquisitiveness never left me.”

After graduation, most of The Aletheia’s founders I managed to contact had drifted across the country. Lowery lives in Maryland, Link made it to New Jersey. Czerak did journalism and PR in Chicago for a few years before moving to the suburbs to work for Illinois Benedictine College (now Benedictine University).

Mary Jeanne Klasen, The Aletheia’s first editor-in-chief, taught high school math in Chicago until she died in 2013. She lived in her apartment at 847 West Dickens – next door to The Aletheia’s original office – long after the paper had shuttered.

Names tend to warp over decades. For instance: Joseph Link spent the entirety of his undergrad writing under his middle name – Larry, short for Lawrence – before switching back to Joe post-graduation in order to avoid the alliteration.

As I started to make contact and talk to old members of The Aletheia, they had a tendency to ask the same questions: who had I managed to contact? Who was still around? How were they?

Gerry Czerak was one of the first people to ask who I’d found. It was early in my research, and I had just sent out my first batch of emails. When I replied to him, I quickly listed a handful of people who’d responded, as well as a couple of people I’d found in obituaries: Mary Jeanne Klasen, and – for reasons I will never fully understand – Larry Link.

A few days later, I got a reply from Czerak. “Ouch,” he wrote. “Larry Link was one of my best friends from the DePaulia and Aletheia. Sad to hear.”

My stomach dropped a few inches after I’d read that. I wasn’t sure what I expected, but I hadn’t wanted to bring anyone grief.

Then I looked back at my inbox. Two emails above Czerak’s, a message had appeared from a Joseph Lawrence Link, who was – in fact – very alive. My stomach plummeted. I immediately responded to Czerak with an emphatic JUST KIDDING before apologizing effusively and giving him Link’s email. I assumed he would not be interested in an interview.

Thankfully, I was wrong. In early April, we talked for a couple hours, and afterwards he emailed me to say thanks for putting him in contact with Link. The two had been catching up, and Czerak forwarded me the first letter he’d sent in the exchange. In a five-page letter with single-spaced, 11-point Garamond font, he wrote:

Certainly you are among the old friends from our earlier times, and we treasure that fact. Now we can get reacquainted via the ether, but that is better than not at all…. I am sure we both look exactly now like we did on pages 152-53 of the 1969 DePaul yearbook (the last one I was able to keep my hands on)!

Odd too that you wrote the story in Year 1 about how the paper came about, and I wrote in 1971 about how we decided to end it…. Looking forward to future catch-up with you – glad to know you are happy and well. Whenever you talk with Barbara again, please say hello for us.

Cheers for Easter and Spring!

Gerry

Correction: An earlier version of this piece used The Michigan Daily’s spelling of Ernie Kopczynski’s last name, which was incorrect.

An earlier version also stated that Gerry Czerak taught at Illinois Benedictine College, which was incorrect. He was a marketing and communications director.

DePaul’s Secret Zine Scene – Fourteen East

5 October

[…] was first used to define radical anti-war newspapers that circulated between 1964 and 1973 (take DePaul’s own counter-culture newspaper, The Aletheia, for example). How the phrase recirculated in Chicago literary communities is lost to […]