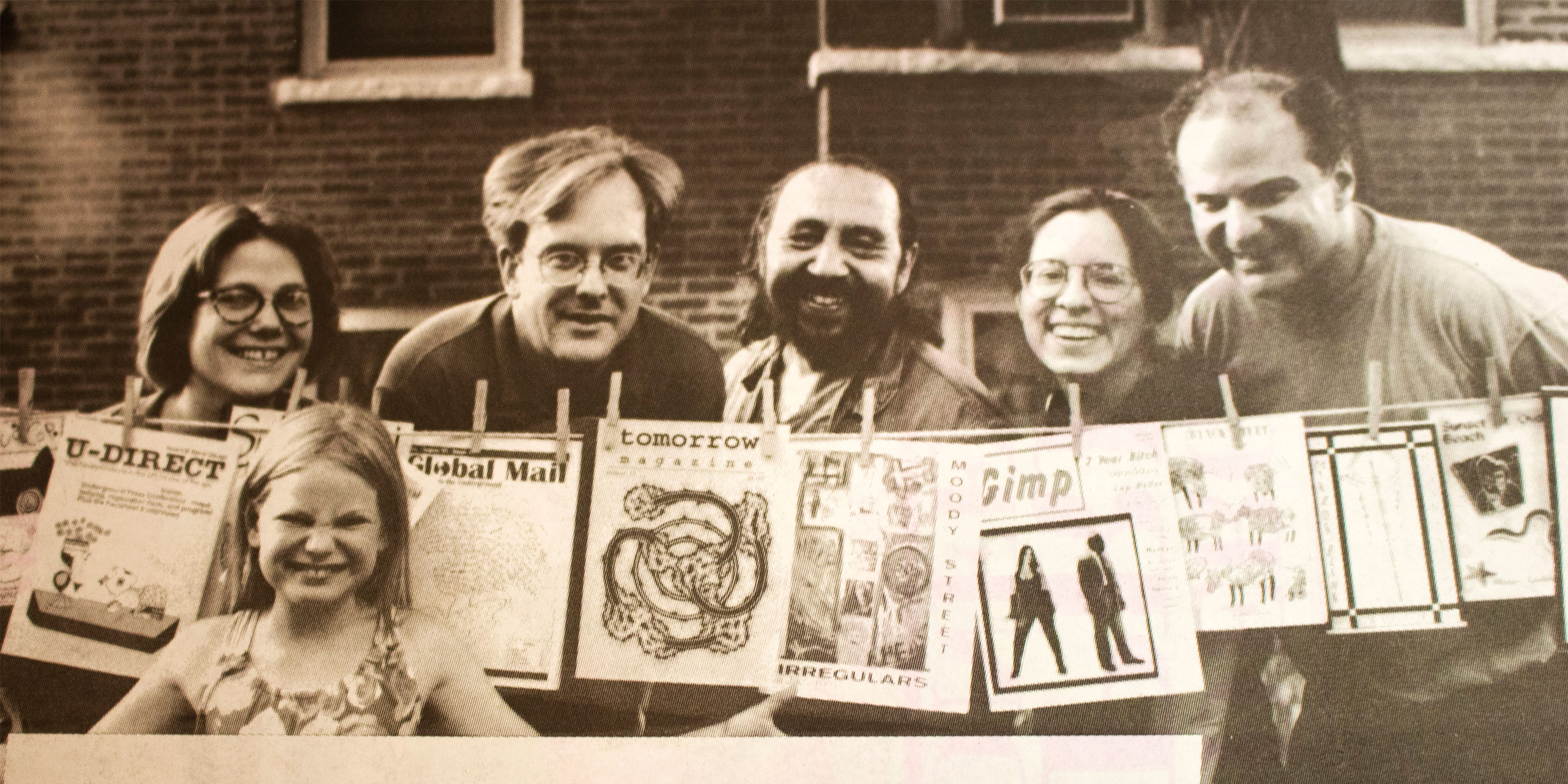

Sprawled across the university quad were tables of mismatched, pamphlet-like publications. Some were black and white with grainy imagery and chaotic font calling for abortion rights. Others were saddle-stitched and erotic-poetry themed. Some tables included neat rows of chronicled publications, while others were piled with one-off issues. People walked between rows, flipping through pages and swapping booklets.

It was the Underground Press Conference: the meeting ground of the ‘90s zine scene, the mail order, underground press movement dedicated to unapologetic artistic freedom.

It was an abnormally pleasant day for the middle of August in Chicago. DePaul University’s head librarian Kathryn DeGraff and conference founder Batya Hernandez moved swiftly through the crowd, grabbing as many copies of zines as they could carry. This was DePaul history, zine history. It needed to be archived.

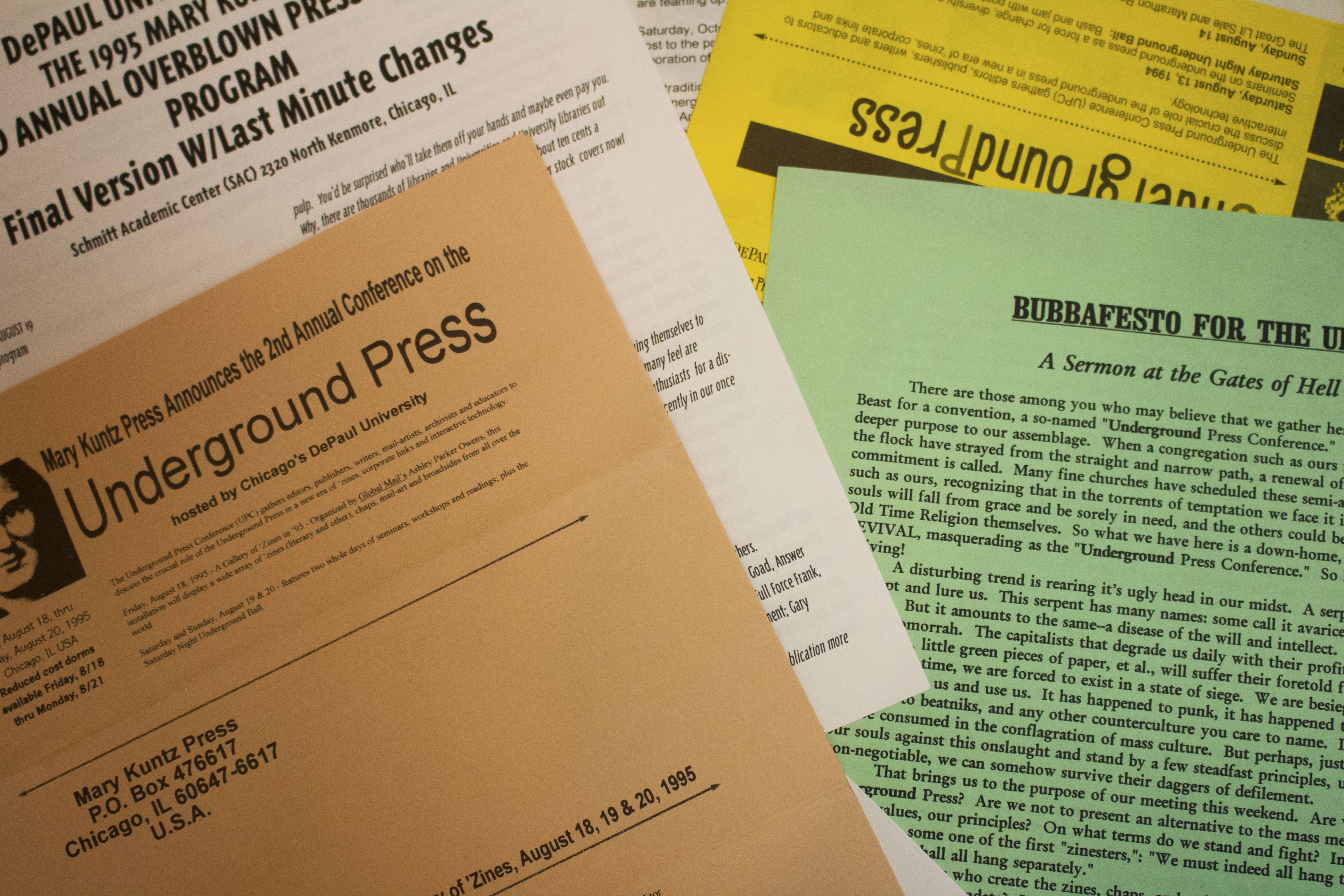

Official Underground Press Conference paraphernalia on display at the DePaul Special Collections Archives. (Madeline Happold, 14 East)

In August 1994 and ‘95, DePaul hosted the Underground Press Conference (UPC), defined as a gathering of “editors, publishers, writers, mail-artists, archivists and educators to discuss the crucial role of the Underground Press Conference in a new era of zines, corporate links and interactive technology,” according the conference’s program. The conference was the first of its kind, gathering zine creators — zinesters, they were nicknamed — to talk artistry, free speech, independent publishing and alternative culture.

Like any artistic movement, it wasn’t meant to last. After two years at DePaul, and one at the Chicago Cultural Center, the Underground Press Conference disbanded. While short-lived, it became a paper trail to an arts and zine movement now memorialized in DePaul’s library catalogues and followed by trendy zine fests nationwide.

The Zine Queen

It was May 29, 1992, and the day of Hernandez’s graduation from Columbia College Chicago. The single mother, now fiction-writing graduate, had no plans to celebrate, but her ex-in-laws offered to watch the kids for the night. She hit up Smilin’ Jim’s — owned by a friend’s brother, the bar had become a place to blow off steam and hang out for Hernandez. There, she met Shane Bugbee, editor of “Naked Aggression.” He mentioned he was looking for a fiction editor and thought Hernandez would be perfect for the position.

(Though Bugbee said he does not remember asking Hernandez to be an editor for his zine, he does remember meeting Hernandez and introducing her to self-publishing.)

Hernandez was less convinced. Why did Bugbee coincidentally need a fiction editor, and what even was a zine, anyway? Bugbee told her to wait, he had some submissions outside in his car. He returned with two U.S. mail bags full of little, stapled paper books. Intrigued, Hernandez took the mail bags home, flipped through the submissions, and was hooked.

“It was so [do-it-yourself],” said Hernandez. “That’s what I loved about it. I loved all the people from all around the world that I was meeting through the mail.”

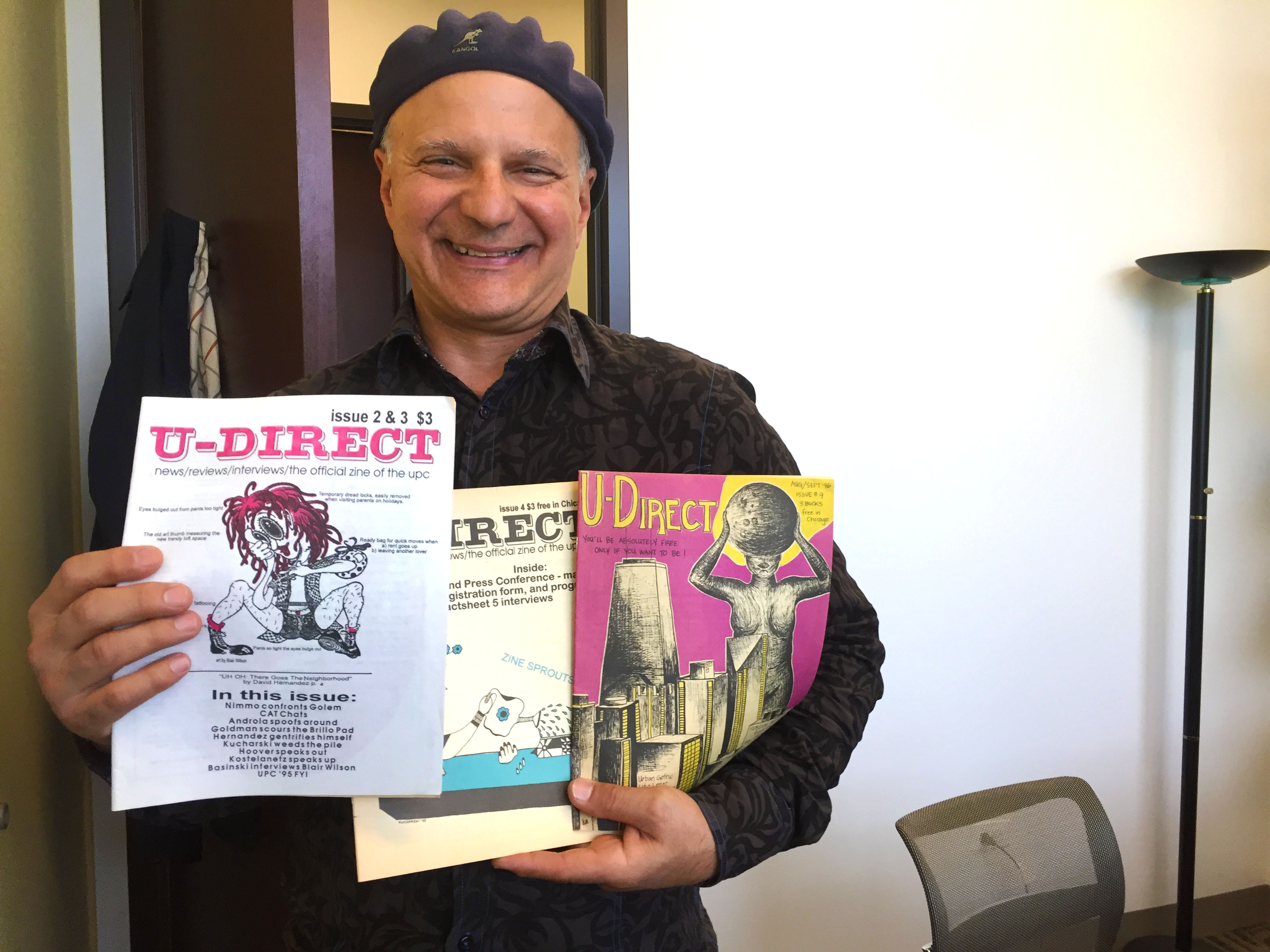

Hernandez, founder of the Underground Press Conference. (Madeline Happold, 14 East)

So what is a zine? According to programs distributed at UPC, a zine is a “self-published, non-commercial publication done by a variety of individuals… zines are among the most democratic of media, requiring not much more than having some idea or something to say.” Zines’ do-it-yourself (DIY) nature is lo-fi and outlandish, with collage designs, spitfire commentary and short life spans. Most zines are touch-and-go, their candidness contained to, at most, a handful of issues.

The UPC definition is deliberately broad, said Hernandez, to include any handmade publication on a variety of topics, like punk music or photography. But zine creation today is much different than in the mid-‘90s — digital zines allow for cheaper, faster distribution and more interactive design elements like gifs, videos and links. Most noticeably, there is the absence of physically flipping through pages.

“It’s [a] self-produced, self-made, DIY publication, whether it’s an internet publication, an e-publication or a paper publication,” said Hernandez. “But the classic zine is the Xerox [scan] with the staples.”

Zines inspired Hernandez to start her own underground press, Mary Kuntz Press, with friend Gabriele Strohschen. The feminist zine — the title is a variation of “happy vagina,” but you can use your imagination — featured the moniker of an old suffragette photo to have the appearance of an “old, established press.”

“The whole thing was a prank,” said Hernandez. “It was very feminist; very in your face.”

Strohschen helped Hernandez co-found Mary Kuntz Press and the ’94 Underground Press Conference. (Madeline Happold, 14 East)

Strohschen also had her own zine, “WISdom,” an extension of her community organizing group World Independence Society. She got involved in spoken word performances at the now-closed Weeds Tavern, where she met Chicago poet David Hernandez, Bayta Hernandez’s husband, who introduced the pair.

Through the press Hernandez formed a community with other zinesters, but their only correspondence was through snail mail or email. There was no personal connection or face to match a written voice. In 1994, Hernandez and Strohschen decided to gather a copy of “Factsheet 5,” a quarterly zine that reviewed other zines from across the world, and bulk-mailed roughly 5,000 surveys to gauge interest in an in-person conference. They received around 1,500 replies.

Underground is not Mainstream

The number of responses was a call to action for the zinesters. At the time, David was a visiting professor at DePaul and wanted to find a way to host the conference at the university. He took the letters of interest to his creative writing colleague Ted Anton.

“It was partly a conference on issues, partly a book sale and partly a how-to about zine[s],” said Anton.

Anton with copies of the UPC’s official conference zine U-Direct. (Madeline Happold, 14 East)

Tim W. Brown, editor of “Tomorrow Magazine,” which printed from 1982 to ‘99, was asked to join the committee, now comprised of the Hernandez pair, Strohschen and Anton. With his experience, he worked with Hernandez on marketing and corresponding with other zinesters.

“[UPC] was a way to learn about the subject as well as to sort of promote your product,” said Brown.

The term “underground press” was first used to define radical anti-war newspapers that circulated between 1964 and 1973 (take DePaul’s own counter-culture newspaper, The Aletheia, for example). How the phrase recirculated in Chicago literary communities is lost to its members, but the definition remains similar. According to Hernandez, underground was just not mainstream. It was building your own community, separate of mass media culture.

Anton brought the proposal to DePaul’s librarians Kathryn DeGraff and Stephanie Quinn, who were interested in hosting the event at DePaul. With some funding from the Illinois Arts Council, dorm rooms donated by the university and a $25 admission charge, the first UPC was set to take place August 12-14, 1994, with a second annual conference the following year.

In each of those two years, the conference brought roughly 300 community members and zinesters from California to New York. The events even gained larger attention, after being featured in the Chicago Reader and now-defunct Chicago City Pages.

“I had three or four of them stay out of my house on mattresses on the floor,” said Strohschen.

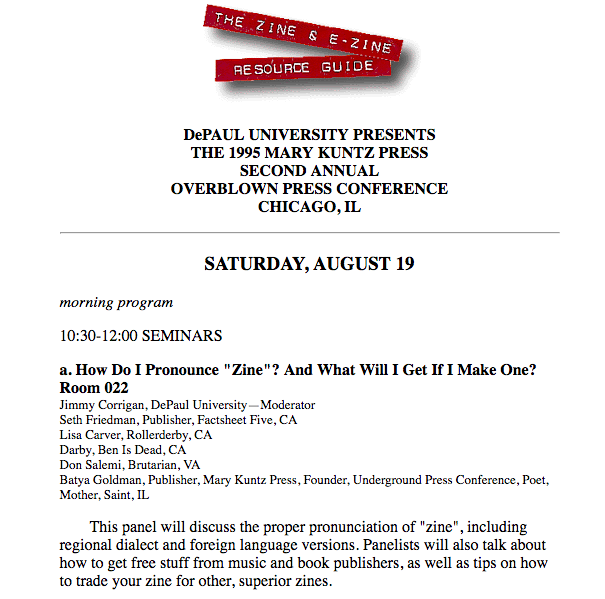

Featured zinesters and readers included Jen Angel of angsty rock and anti-capitalist zine “F—tooth,” R. Seth Friedman of the zine reviewer “Factsheet 5,” Mike Brehm of “Storyhead,” Chip Rowe of “Chip’s Closet Cleaner” and more. The conference even distributed its own “U-Direct” zine, including think-pieces on zine creation, raunchy poetry and sarcastic op-eds.

The conference included informational seminars with eclectic topics like “Feminism, Post-Feminism and Grrldom,” “Is the Internet All It’s Cracked up to Be?” and the beginner’s basic “What’s a Zine? And How Do I Make One?” Saturday night would feature a free Underground Ball at the Bop Shop with Sunday bringing the Outdoor Underground Lit Sale and Read-In. There were zine swaps, discussions on free speech and outdoor poetry readings on the surrounding university streets.

“It was either buy a beer or buy a little zine,” said Strohschen.

The conference wasn’t without its controversy, either. One seminar included a panelist stripping naked in front of participants. Another panelist wrote obscenities on the school blackboard — to which was later amended to say, “Let us all f–k peacefully.” Debates could turn argumentative, with the amalgamation of zinesters questioning free press, who had the right to publish and what separated artistry from obscenity.

“It felt like a circus, a kaleidoscope of activity,” said Anton. “It was very exciting; things were scary.”

The conference helped Anton turn his short story into the novel “Eros, Magic and the Murder of Professor Culianu.” He remembers reading the opening scene on Kenmore Street outside DePaul’s Schmitt Academic Center as people walked by, not listening.

“All of a sudden it gave me a greater urgency, like I’ll make sure every word is good if I have to publish it,” said Anton. “That’s sort of how I changed my whole style and it became a book. So it was very cool, the Underground Press, in the evolution of my style.”

Zines — Who Started Them, Anyway?

The Chicago underground poetry and zine scene of the ‘90s wasn’t all snaps and zine swaps. Trying to break into the scene included a bit of hazing, and arguments weren’t uncommon at readings.

“It was rough and tumble,” said Strohschen. “It wasn’t always nice.”

Surrounding the conception of the conference was the quintessential artist debate of underground versus mainstream. Some participants were wary of the the event’s connection to the university as an institution, or the “Belly of the Beast,” according to the Bubbafesto for the UPC — a spoof on the conference’s manifesto written by a so-called Father A. Wolfgang of the Church of Bubba.

“People questioned even the idea of having a conference because it was somehow selling out, especially being affiliated with the university,” said Brown.

Some, like Bugbee of “Naked Aggression,” argued about the conference’s accessibility. Since the event charged an admission fee, he argued it excluded low-income voices from the Chicago scene. And once the conference fee was collected, where was the money to go?

The Bubbafesto echoes the anti-capitalist sentiment of the conference: “Tell your readers where the money goes. Demand financial statements from things like the Underground Press Conference and ‘Factsheet Five’ — see where the money is going, and hold them accountable for the profits made in the scene.”

UPC also promoted free speech and free press, which brought a variety of competing voices. Arguments would rise over seminar topics or opposing viewpoints. There was also disagreement over seminar topics — which ranged from “How Do I Pronounce ‘Zine’?” and “What Will I Get If I Make One?” to “F—k ME!?! F—k YOU!!! Settling Your Difference in the Zine World” — with some arguing topics were too beginner-focused.

“I think a few people kind of got into each other’s hair, but by-and-large it was very amicable,” said Strohschen.

Strohschen left the planning committee after the 1994 conference. Other organizers got tired of the long volunteer hours and were ready to settle into more stable, “adult” jobs, according to Strohschen. They also got tired of the community backlash and “flame wars” that could spark in online chatrooms, according to Hernandez.

At the 1995 conference, Steven Svymbersky, owner of well-known zine bookstore Quimby’s, and zinester Dan Kelly pranked the event, distributing a fake conference program after Saturday’s keynote address. The alternative conference program included spoof seminars like “The Reviewer’s Dunk Tank” and panelists including the likes of Kurt Cobain and The Professor from Gilligan’s Island.

Excerpts from the 1995 prank conference pamphlet. Screenshot from zinebook.com

In 1996, UPC’s third and final year, the conference partnered with the city’s Independent Comics Expo (ICE) for a final event at the Chicago Cultural Center, but by then the scrappy DIY charm began to fade. Slam poetry and e-zines were on the rise, and print was too expensive and time-consuming in comparison. For Hernandez, the event had run its course. The Underground Press Conference had blossomed then vanished, just like the zines that scattered DePaul’s quad those two August weekends.

“We captured something at the heyday and the end at the same time,” said Hernandez.

‘The Rest is Zine History’

Almost 25 years later, DePaul’s Special Collections Archives still houses a collection of over 300 zines from the two-year conference. Students are allowed to sit in the special collections room and check out one box at a time, whether to peruse or to study.

But the zines weren’t moved immediately to the library archives following that warm August conference in ‘95. Due to the unique nature of zines, the archival and organizational process is complicated. Instead, those copies collected by DeGraff and Hernandez were kept in boxes and moved to storage for almost a decade — until Bradley Adita came along.

Adita was a zinester himself, making zines in high school after receiving one from a mutual friend (Adita’s first zine was all about juggling). As a student at the University of Iowa, Adita heard about the conference after curating his own art and zine shows.

So in 2004 Adita, now a Chicago resident, visited DePaul in hopes of sifting through the collection. He found dozens of boxes filled with unorganized zines. The library had yet to create a finding aid, or index, for the collection. Adita volunteered.

“I didn’t really know what I was getting into until it was happening,” he said.

Zines archived in DePaul’s Special Collection Archives are separated by themes such as music, poetry or riot grrrl. (Madeline Happold, 14 East)

Size matters when organizing the collection, said Adita. Zines were categorized by themes, such as music, poetry or politics. The full system and cataloging took roughly a year, with Adita visiting the library every other week to help sort. He said zines serve as a means of connection and inspiration for creator and reader both.

Much like Doc Martens or the lovable Winona Ryder, zines have made their comeback. Despite the fears of those at the conferences, the internet didn’t kill zines. Instead, it offered a new platform for creation, while driving those that wanted to move off screen back to the paper product.

In 2010, Chicago Zine Fest seemed to revitalize the sense of community started by the Underground Press Conference. The zine fest, now in its ninth year, includes a zine fair, readings and featured workshops. In May, DePaul hosted an event in partnership with Chicago Zine Fest on the history of its zine archives, which sold out less than 24 hours after being advertised.

Quimby’s in Wicker Park still remains a haven for local zinesters to sell and share their work. The bookstore also hosts Zlumber Party, an all-night zine-making event where zinesters stay overnight at the store. E-zines, or online zines, are also a popular medium due to their interactivity and low production cost. But, more about that here:

In the mid-‘90s, though, before technology and social media made it easier to connect, zines thrived as social currency and connection. Zines were an intricate string of pen pals exchanging little booklets via mailbox, when checking the mail was more than just bills and coupons. “Factsheet 5” listed thousands of zines — and those were simply the ones recorded. The Underground Press Conference sat at the moment between Xerox and internet.

In a ‘95 Underground Press Conference U-Direct letter from the editor, Hernandez reflected on the conception of the conference:

“I thought maybe we could really build an international zine community. I thought maybe we could even get academic and mainstream individuals to help out with resources. One long term zinester said it’ll never work….

I don’t take no for an answer very easily and when my husband David Hernandez was teaching for a semester at DePaul he suggested asking them for a space and maybe a little cash… ‘No way.’ The rest is zine history.”

Header image courtesy of DePaul Special Collections Archives

Correction: A quote by Bradley Adita has been removed for clarity. The original quote was not in reference to zines.

NO COMMENT