A buzzed Matthew McCarty stumbles into the 7/11 at the corner of Broadway and Waveland at 1:56 a.m. in late July 2016. Lips parched and craving nicotine, he’s looking to buy a pack of Marlboro Golds since he had just finished his last pack. Just weeks earlier, Chicago raised the age to buy cigarettes from 18 to 21. McCarty was 19.

He was sporting the beginnings of a scruffy beard and wore a light sweater with brown chinos; he looked old enough. He walked up to the counter.

“Can I get those Marlboros up there?” he asks, pointing up to the Golds.

The cashier looks at McCarty and then turns back to pick out the carton of cigarettes. He turns back and rings them up. McCarty isn’t surprised by the cashier’s response.

“That’ll be $12.30.”

McCarty started smoking at the age of 18, as many young adults do to mark their passage into adulthood. “It was a new freedom for me, a time to explore and try new things,” he says. “Something to check off the bucket list, right?”

McCarty grew up in Bloomington, Indiana, where he became a social smoker as a high school senior — only having two or three cigarettes a day with friends. He was only a light smoker since he used to be a track athlete and member of the cross country team. At least half the kids at his high school were smokers, he notes, and that it was a “pretty casual thing.” The legal age to buy cigarettes in Indiana is still 18, but that wasn’t an issue for him.

Coming to DePaul marked a change in his smoking habits, though. He smoked less socially and more out of habit or stress-relief. He also found that DePaul’s smokers were different than those back home. “I noticed it more here,” he says. “People here make a big deal out of it. They smoke outside where they can be seen.” McCarty nods to the window where a DePaul student had just posted up outside to light a cigarette.

“For a while I was smoking, maybe 10 cigs a day? I dunno but I developed a nicotine dependency here at DePaul,” he says, laughing. “I mean, I know that it’s bad for me and I’ve been taking a psychology class where we’re looking at addictions, like binge drinking and smoking, so I know that I’m especially susceptible to the addiction and I get why they raised the age.”

In 2005, Needham, MA, was the first town in the United States to try the Tobacco 21 policy, which meant raising the age of tobacco purchase to 21. The reason for the change was to lower the frequency of adolescent smoking, making it more difficult for high schoolers to obtain cigarettes. According to Tobacco Twenty-One, Needham High School saw a 50 percent drop in students that reported smoking cigarettes in 2010. Today, the age to buy tobacco in the rest of Massachusetts is still 18, however.

“It’s just good public health practice,” said Evonda Thomas-Smith, the director of Health and Human Services of Evanston— the first town in Illinois to follow Needham’s example.

The ordinance change in Evanston is only two years old, so no longitudinal study has really been completed. Yet Thomas-Smith can vouch for the science behind the ordinance change, saying not smoking during adolescence “really decreases the addictive nature of nicotine in our youth population.”

Adolescence is usually defined as the onset of puberty, or sexual maturation, but the period for brain maturation can last years after puberty, up to the age of 25. Studies have shown that crucial brain development still occurs after 18. The adolescent brain changes tremendously during this period, especially the limbic system which plays a role in emotional regulation, risk taking and motivations.

During adolescence, the brain is still engaging in synaptic pruning— the process by which the brain finds the most effective neuron pathways. The introduction of nicotine to that environment pushes the brain to include it as a routine behavior. In turn, addictive behaviors can be hardwired into the brain and become much harder to quit in adulthood.

Nicotine also has detrimental long term effects to the brain’s response to serotonin and other neurotransmitters. While the brain is fine tuning reasoning skills, priority setting and impulse control, nicotine dependence makes an impact on those behaviors.

To Smoke or Not to Smoke

All states highlighted blue in the map above have enacted Tobacco 21 laws in one or more counties. Graphic by Jake Ekdahl and Maxwell Newsom

Chicago legislators reportedly cited neurological studies concerning high addiction levels in adolescents from the ages of 18 to 21 when proposing the change. At first, McCarty was furious that he could no longer buy cigarettes in Chicago. But he quickly realized that it was easier and cheaper just to go back to Indiana to buy them.

“It makes sense that they did that as far as consistency,” McCarty explains when asked about 18 being the age of adulthood. “You can drink at 21 so that should just be the standard across the board. Same for voting and being drafted.” Tobacco 21 in Needham and Evanston both cited alcohol age limits as influences for Tobacco 21.

Now, at 20 years old, it seems fairly easy for him to get cigarettes now since he can just walk into a convenience store in the waking hours of the morning and probably not get carded or just make the drive to Indiana and buy a carton of cigarettes there to avoid being heavily taxed. Despite being able to easily get cigarettes, the change has been having an effect. Lately, he has been smoking less and he shows off his e-cigarette, which is helping him wean off his cigarette habit.

Not all those affected by the law think as highly of it, though. Alex Leonard, a 20-year-old DePaul student, says the law is unfair since it completely disregards those who were previously able to buy cigarettes. “My friends and I just go to greater lengths to get cigarettes now,” Leonard says. “I buy mine in Missouri when I see my family.”

Leonard began smoking in high school, much like McCarty, when she was 17.

“I started smoking when I transferred high schools because everyone else did. That’s how everyone socialized there,” she says, while reminiscing about home.

Socializing was as much a theme for Leonard as it was for McCarty: “It gives you a good out when you feel overwhelmed and it makes for better conversations at parties.”

Leonard has no need to buy cigarettes in the near future since she already has two cartons to hold her over, courtesy of her grandmother. However, she doesn’t have plans to finish smoking the cartons, which contain ten packs each. “I don’t even smoke that much, so I dunno what I’m gonna do with all of them,” she says. “I’m trying to give some away.”

Even while trying to give away her cigarettes, Leonard isn’t sure what to make of the effectiveness of the law in Chicago. “I did quit for six months, but once I started going to parties and the stress of school, I started again,” she said. “I think it might help curb smoking but I’m not sure. The convenience store by my high school wouldn’t card 14 year-olds so…”

“People are gonna get cigarettes and stuff regardless, somehow,” says tobacco clerk and vapor expert Hiroki, 21, while he helps a customer select a vape flavor in the mid-afternoon. “I think it’s an unnecessary inconvenience to a lot of people.”

Hiroki works at the Roots Smoke and Vapor shop, located on 4006 N. Sheridan Road, which specializes in vapes — much like the one McCarty uses — and other nicotine products.

“I’m the government’s poster-boy for why this could potentially be bad. The first thing I puffed on was not a cigarette— it was one of these,” Hiroki says while pointing to the cloud of vapor leaving his customer’s mouth.

He doesn’t see the law as being the most effective way of getting teens to cut down on smoking, and his coworker agreed.

“Maybe it’ll work. I started smoking at 16 or 17. I had friends that bought them,” says Omar, the other vape expert at Roots. The inconsistency of adulthood in the eyes of the law bothered him as much as it did for McCarty.

“The weird thing is, you’re 18 — you can go to war but you can’t smoke cigarettes? Or have a beer till you’re 21? It’s kind of stupid. If something affects your brain in a negative way, it’s war I’m sure,” he says, while gingerly petting Frank, the German shepherd that joins them behind the counter.

Both Hiroki and Omar agreed on the need for a cultural shift in consumption habits, using European teen drinking as a prime example. They said that advocacy and education were the keys to preventing addictive behaviors. The Truth TV campaign commercials advising teens against smoking and testimonials of former smokers seem to be a step in the right direction.

Hiroki chimed in after ringing up some cigarillos for a customer that had just walked in. “If people understood the effects of it and how to use it, you can use it properly.”

“Increasing the minimum legal sales age to 21 could result in a 12 percent drop, across the board, for adults and youth,” says Lea Bacci, the Lake County Health Department assistant prevention coordinator. This prediction comes from a March 2015 report from the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies.

Deerfield is the latest town in Illinois to implement Tobacco 21 as part of their public health initiatives, changing the age of purchase and sale to 21 in January 2017. Lake County still uses the age of 18 for tobacco purchase, as does the state of Illinois. Last year, Hawaii and California became the first states to implement a statewide Tobacco 21 policy.

“If you think back to high school, the teenage brain— your decision making capabilities, weren’t what they are now, as a senior in college,” Bacci says.

Bacci cited the same studies and readings that Thomas-Smith did when justifying the ordinance. “The pre-frontal cortex in the brain is still developing in the teenage years. Because of that development, initiating drug use has a significant impact on the pre-frontal cortex.”

She also foresaw success in adolescent populations in Chicago. “In the beginning, people are kind of upset and frustrated about it,” she says. “But then over time, you see the effects.”

As far as enforcement of the ordinance, Bacci and Thomas-Smith were able to point to compliance checks that resulted in very low failure rates. These checks are conducted by underage teens in the company of a detective in an unmarked vehicle. In Lake County, the first violation results in a $250 fine; the 2nd and subsequent offenses result in a $500 fine or eventual suspension of the tobacco license. Evanston has a similar policy.

“Most smokers know after they pick up the habit that they have to quit,” McCarty says and then explains more about the controls on his Juul e-cigarette. The cartridges have different flavors and nicotine levels so you can get your nicotine fix without the harshness and without burning up your throat and lungs. In his eyes, it’s a way to avoid the effects of smoke inhalation.

“I think it’ll be good in the long term,” he says when addressing the new ordinance.

McCarty’s friend Alex walks in, past the coffee shop, to meet him.

“Hey man, thanks for coming by. Can I bum a cig?” asks McCarty as he zips up his jacket. Alex nods and they both venture outside into the windy and blustery night that Chicago offers.

Both struggle to light their cigarettes in the wind, and have to cup their hands around their lighter so a flame can be produced. After a few flicks of the lighter, both find success in lighting their cigarettes and begin to puff away.

McCarty has seen the effects of his addiction and its inevitable conclusion up close. A close family friend— his mother’s high school friend— had recently passed away due to lung cancer. McCarty described her as a “pack a day smoker” for most of her life.

“That’s something I think of when smoking,” he says when asked if he has hopes of eventually quitting.

“They do kill in the end.”

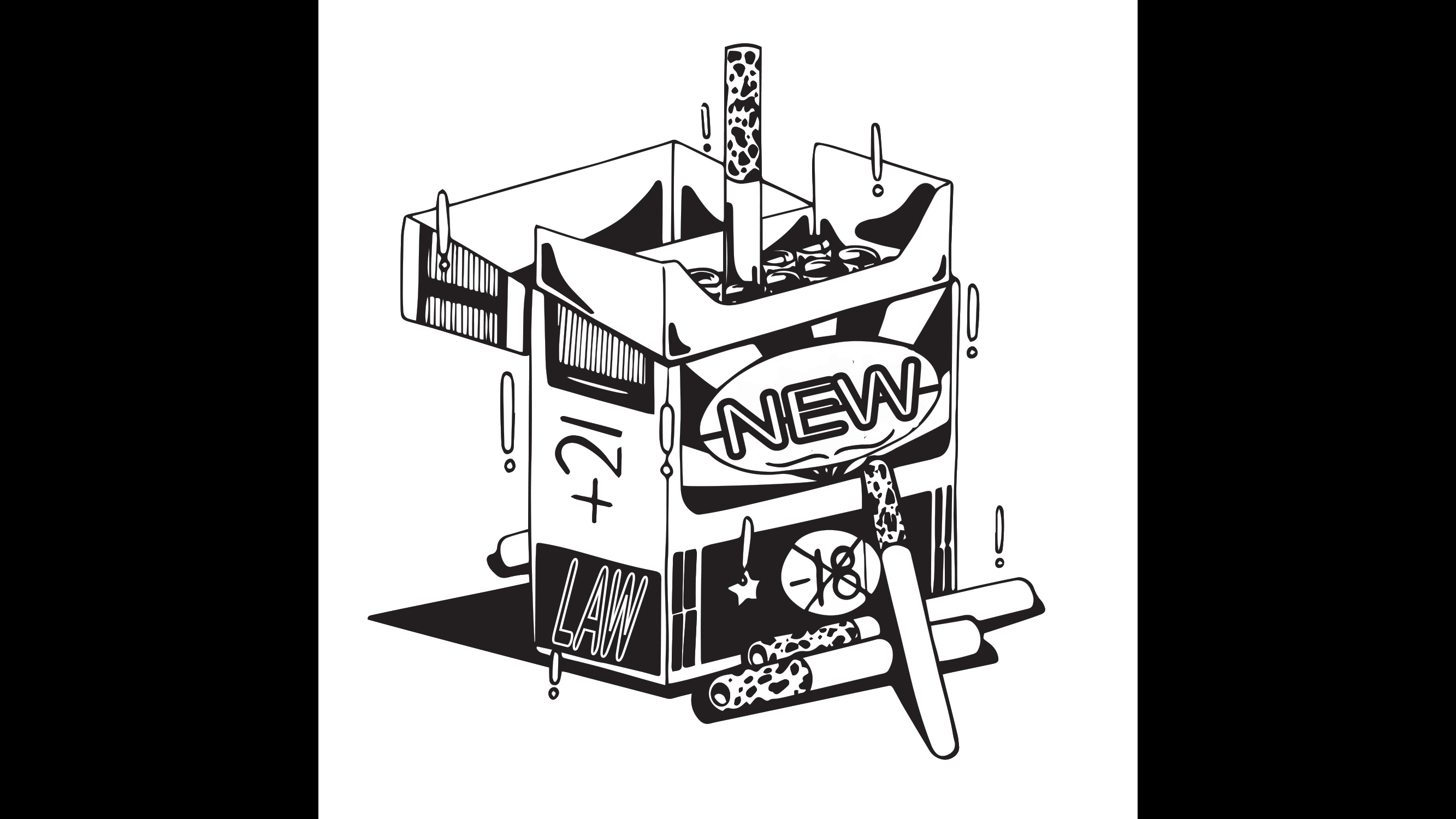

Header illustration courtesy of Joey Stupor.

Correction: an earlier version of this story referred to Bloomington, Idaho instead of Bloomington, Indiana.

NO COMMENT