Looking for Answers at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office.

In 2006, Garry Henning’s 12-year-old grandson Quadrevion — Dre for short — disappeared near the family’s Milwaukee home. He had gone outside to play with a friend and never returned, gone “without a trace,” his grandfather said.

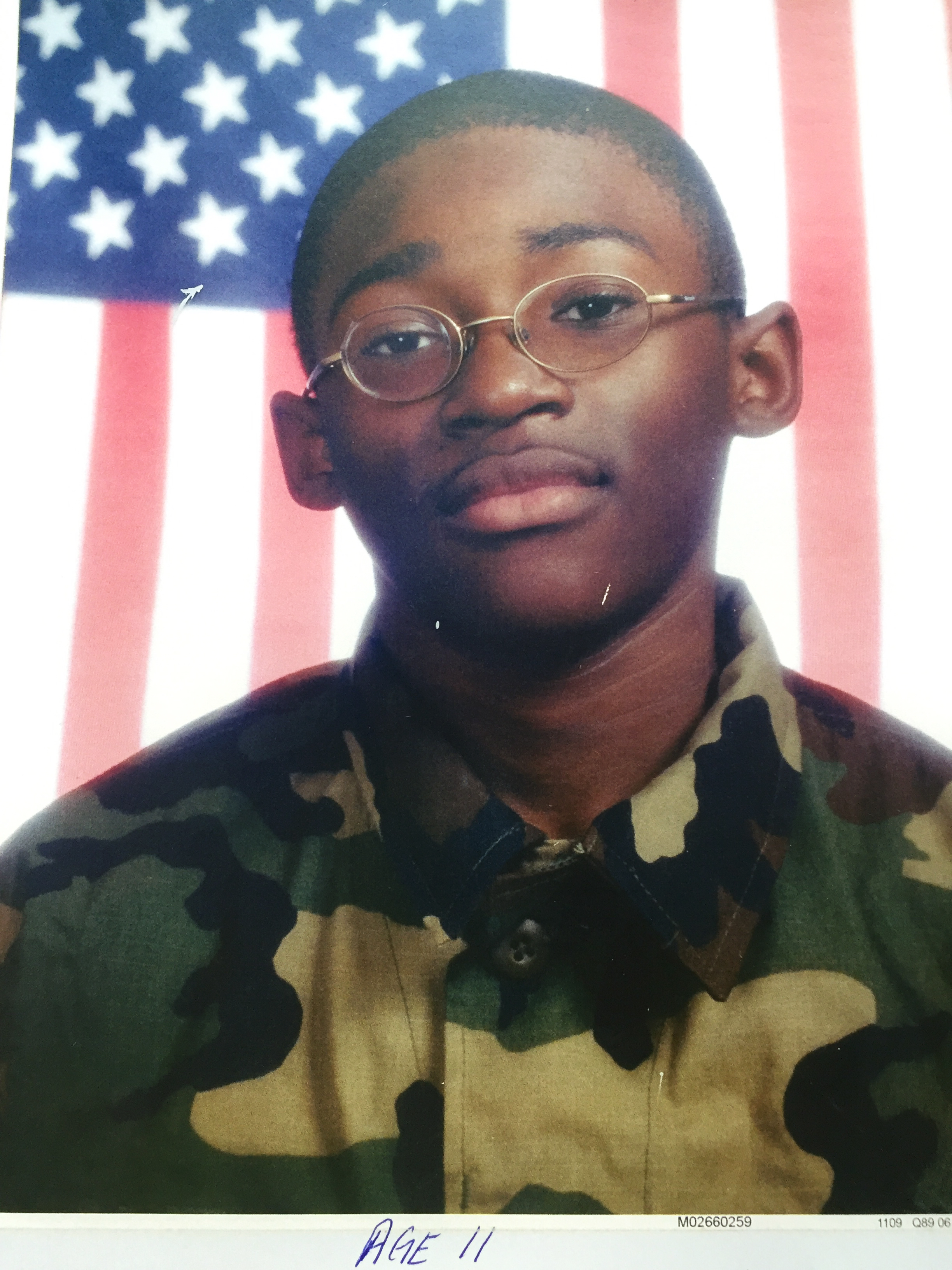

Wracked with grief, the family filed a police report and waited for news. Dre and his best friend, 11-year-old Purvis Virginia Parker, were found dead of an apparent drowning 27 days later.

“There is never closure,” Henning told me. “Yes, I know where he’s buried. But I still wonder why. I still wonder how. And what about other family members who have not found their bodies?”

Quadrevion “Dre” Henning. Photo courtesy of Garry Henning.

It’s that sense of familiarity — knowing what it’s like to grieve without answers — that brought Henning as a volunteer to The Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office’s second annual Missing Persons Day, held Saturday, April 28, in its office on Harrison Street. Here, families with loved ones missing for more than one month could file police reports, talk to emotional support counselors and offer DNA samples to be entered in the National Missing and Unidentified Persons Database with the hope that their efforts might lead to identification.

Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Ponni Arunkumar said the event mirrors similar efforts from other large metropolitan areas like New York City, which launched its Missing Persons Day in 2014.

“We are a central location in a big city and through hosting this event, we will be able to help lots of people in the Chicagoland area and surrounding suburbs, surrounding counties,” Arunkumar said.

On the day of the event, a procession of organizations — chaplains, The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and many others — flanked the walls of the office’s sun-drenched lobby to offer iterations of emotional support to attendees.

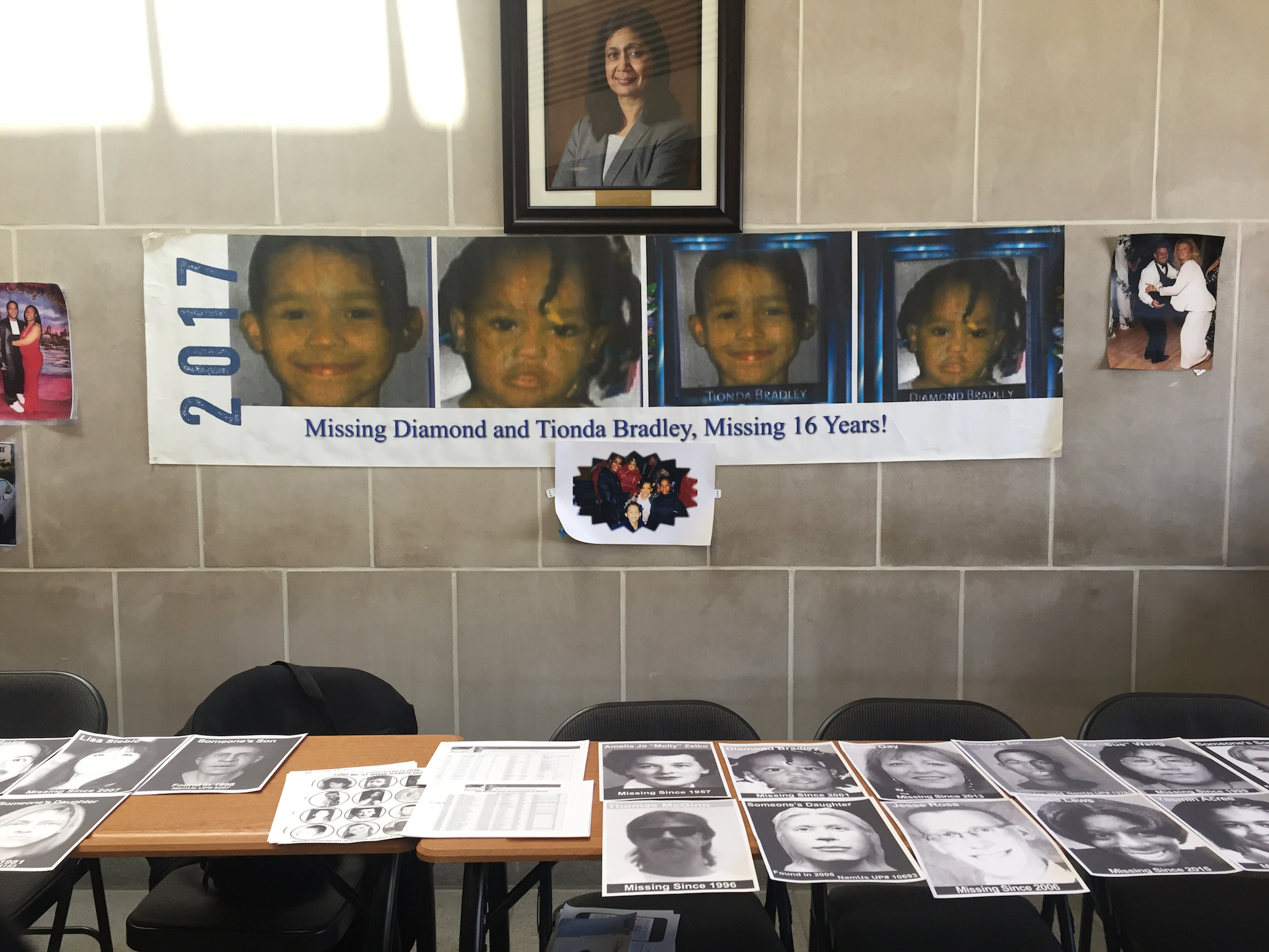

Henning, for instance, is a volunteer at Team Hope, a branch of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children that provides counseling services to families of missing children. Others came to represent their own experiences with missing loved ones, like Jeff Skemp, whose 13-year-old daughter Rachel (“bubbly, smart, a bit of a hippie,” he said) went missing from Bolingbrook in January 1996, or Shelia Bradley-Smith, whose 3- and- 10-year-old grand-nieces Tionda and Diamond Bradley were last seen at 35th and Cottage Grove in 2001.

The lineup of volunteers sat in front of a series of prints on the wall depicting people smiling and dancing or posing in formal wear, photos that looked more like something you’d see on a fridge than the wall of a county medical examiner’s office.

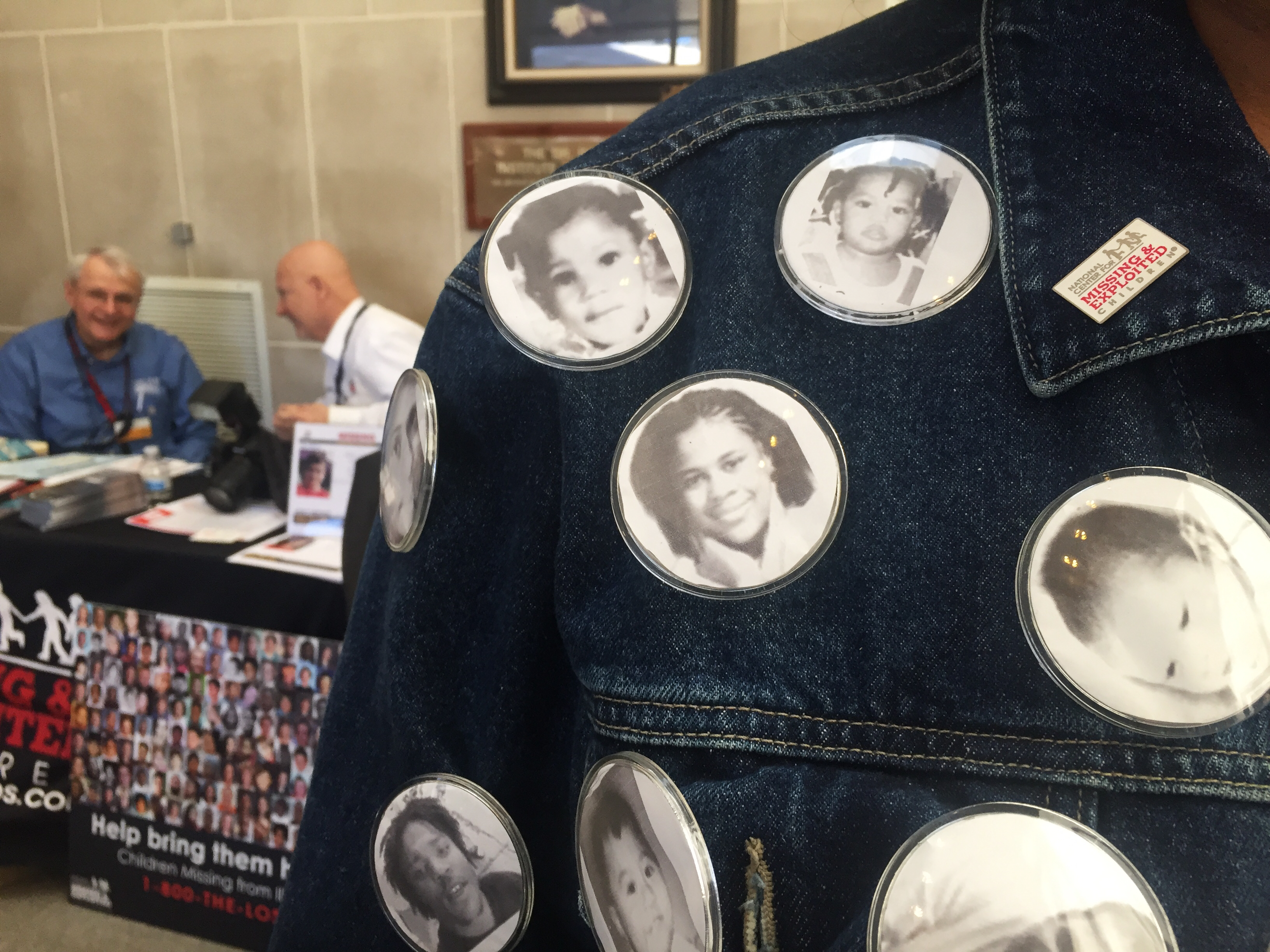

Attendees gather around photos of those missing.(Emma Krupp, 14 East)

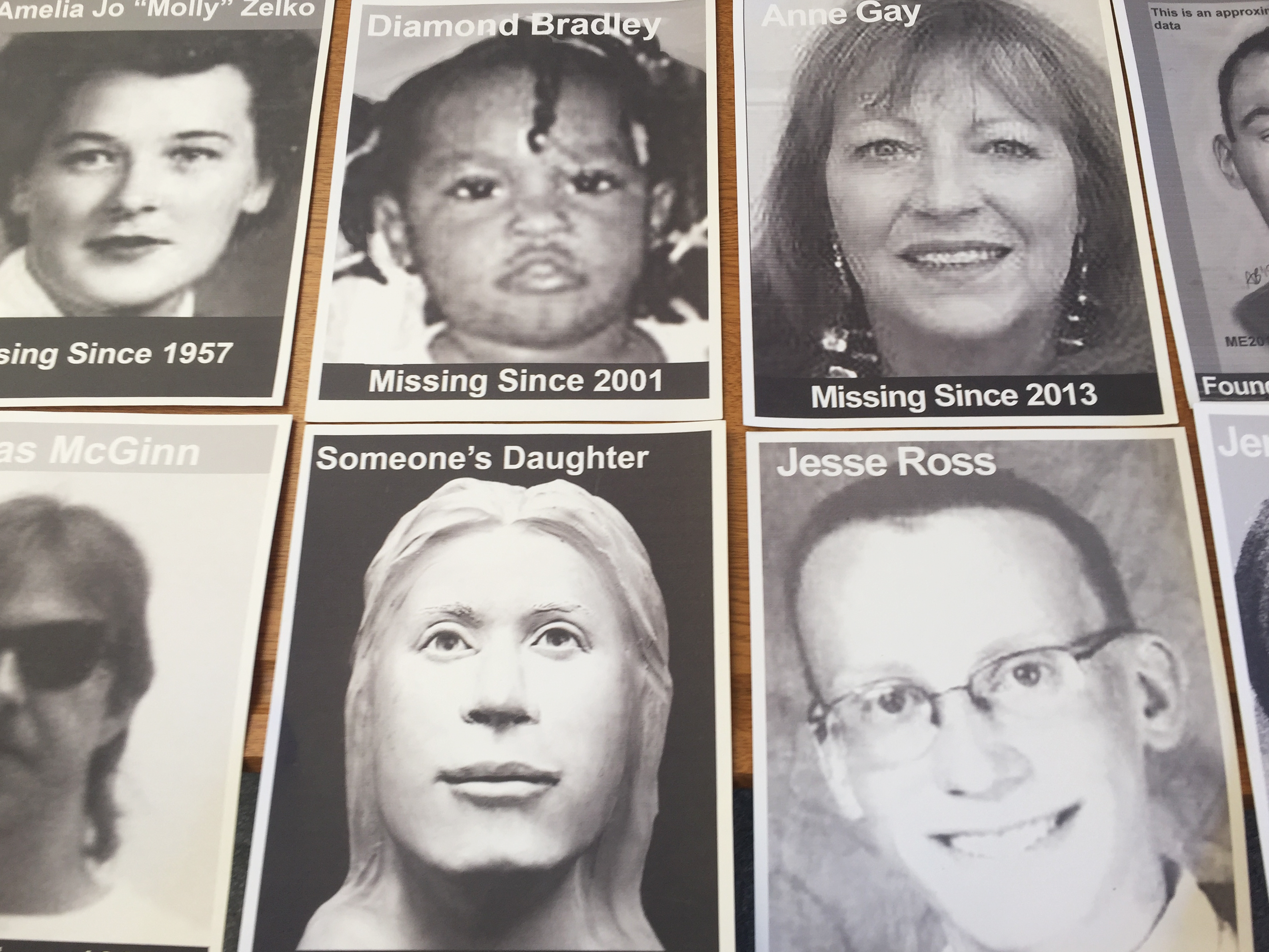

“People have a lack of compassion,” Bradley-Smith said. Her jean jacket was emblazoned with pins depicting the faces of missing people, a swath of black-and-white images studding indigo denim. “They’ve become desensitized [to the fact] that this really does happen. And it doesn’t just happen to a certain race, or creed or color.”

Bradley-Smith wearing her jean jacket, including pins with the faces of those missing. (Emma Krupp, 14 East)

Bradley-Smith came to the event with a cadre of family members, including a teenaged cousin named AJ Carr. Together, Bradley-Smith and Carr talked about how over time, the community — once robust in its support of the missing Bradley sisters — seems to have forgotten about them. The vigils, originally meant to bring home two small girls, are now held for 20- and 27-year-old women. Over time, their memory fades at the edges of public memory; the news reports slow. But this sense of distance, natural for the outside observer, is an impossibility for the Bradley family.

“It was 17 years ago, but every anniversary date I relive the same feelings, the same pain,” Bradley-Smith said. “I remember what I had on that day. I remember what the breeze felt like. That’s only because that day is frozen in time. We’re frozen in time.”

One by one, the volunteers echoed a similar sentiment: You cannot understand what it’s like to lose someone this way until you go through the process yourself, they said.

“People divorce,” Henning said. “Some people become reclusive.” He gestured to himself. “I know it’s hard. I know, because I almost lost my mind.”

Other little-discussed side effects: you forget to eat, take your medication, bathe. You may face hours of interrogation from the police. Sometimes, the police don’t call you back. And although the public will sympathize, they can only fathom glimpses of your grandson Dre, who loved football and wanted to join the military like his dad someday, or your daughter Rachel, who was smart enough to teach herself to read at just three years old. They will forget how Tionda laughed at everything, “even if someone broke their leg, until she realized how serious it was,” Bradley-Smith said.

Public tributes and memorials help — Henning, for instance, runs a football league in his grandson’s memory — but sometimes, the best system of support comes from the inside. Skemp said he tries to attend memorials for other missing people, and has been to events for Diamond and Tionda Bradley. All said they had been to multiple iterations of events like this one in an attempt to connect with families and friends of the recently missing.

“We have a saying,‘We will loan you our strength until you’re strong again,’” Henning said. “These families here, you really feel sad for them. You hope that they have something, some kind of hope. I always tell them: don’t lose hope. Don’t lose hope. Don’t lose hope.”

Headshots from Missing Persons Day. (Emma Krupp, 14 East)

Last year’s event, which drew more than 100 attendees, led to the identification of one body in the morgue. This year, 10 people brought DNA samples in for testing; a spokeswoman for the Medical Examiner’s Office said the results are pending. Now, as before, the families and friends wait.

Among those who brought DNA is Balqees Hamden, who came to the event from suburban Westmont with her mother. Speaking matter-of-factly, she told me her brother, 43-year-old Constanteen Hamden, has been missing since December 7, 2017, when he took a half-hour break from his job at a car dealership and disappeared — no signs, no phone calls, nothing. He’s a people person, and it’s out of character for him to go more than two weeks without checking in.

“We’re just looking for answers,” Hamden said. So far, no major news outlets have picked up his story, and it’s been difficult for detectives to find leads because he doesn’t carry an ID or use social media. Still, his sister and mother remain hopeful he’ll be found alive.

I asked if they’d had a chance to talk to any of the volunteers about this; the younger Hamden shook her head no. They’d only just ascended from the basement, where DNA sampling was being conducted.

Then, as if on cue, Shelia Bradley-Smith walked up to Hamden’s mother, who was sitting quietly behind us in a metal folding chair. Crouching to eye level, she inquired about the circumstances that had led them to Missing Persons Day. What was the name of their loved one? Were they trying to raise awareness about his case? To this, Hamden nodded.

“OK, well have you given DNA?” she asked. “Have you given a DNA sample? OK, OK.” She rattled off a to-do list — she will get them media, she will help them learn how to talk to police. Slowly, she listed her phone number while the two Hamden women scribbled it into their notes. It was important, she said, that they know she was there to help.

“Tionda and Diamond Bradley up there? Those are my nieces,” Bradley-Smith said, pointing at the girls’ blown-up portraits hung on the back wall. “You’re not alone in here.”

Header image by Emma Krupp

NO COMMENT