A young woman with honey brown hair walked slowly across Columbus Drive. Careful and measured, each step appeared more hesitant than the last.

The glow of stage lights and street lamps lit up the dark summer night in Grant Park. Pairs of music fans sprinted past the young woman. They raced from one stage to another as Lollapalooza’s 2017 Saturday night headliners took the stage. The young woman moved steadily toward the stage, unaffected by the rush around her.

Meggi Lampen stood behind a fold-out table draped in purple fabric and speckled with buttons reading, “my cleavage is not an invitation to dance with me” and “I feel safe when there are clear and enforced anti-harassment policies.” Situated under the tent-covered Lolla Cares section of the festival — a space dedicated to organizations promoting causes like environmentalism and political activism — Lampen watched as concertgoers moved between stages, hoping one would stop by her table. She was volunteering for Our Music My Body (OMMB), a campaign that promotes consent in Chicago’s music scene.

The young woman caught Lampen’s attention. Lampen, or the large sign above her head that read “Our Music My Body,” must have caught the young woman’s attention, too. She deviated from her path to visit the table.

Lampen gave what she calls her “elevator speech” to the young woman about OMMB — the campaign was created to start the conversation about consent in music spaces and she’s at Lollapalooza to promote awareness. Once Lampen finished, the woman relaxed, leaning onto the table with one arm. She told Lampen that she hadn’t been to Lollapalooza since someone sexually assaulted her at the festival a few years back. Her cheeks now wet with tears, she said she came this year because she liked the lineup and refused to let her perpetrator have any more power.

“I could tell that she needed to talk,” Lampen said. “She wasn’t looking for someone to be like, ‘Oh you’re great let me give you a pep talk.’ It was more like, ‘This is what I’m going to do, I need someone to hold me accountable. I’m so glad you’re here if I need you.’”

In and out of the music scene, harassment and violence is all too prevalent.

Lampen is a junior studying psychology at DePaul University. She began volunteering for OMMB shortly after the Chicago campaign launched in spring 2016 to promote consent in music spaces. She volunteers at venues and festivals a couple times a month. When at shows, she’s usually with another volunteer. They arrive early to set up, making buttons and attaching OMMB pins to booklets with tips for consent and sexual violence resources. When people arrive, Lampen and the other volunteer start conversations about consent — how to ask for it and why it’s important. Lampen said people are usually open to talking and are glad the campaign is there. Sometimes they even share their experiences.

“People will come up and be like, ‘I was just in the pit and someone just grabbed my ass,’” Lampen said, laughing nervously. Not because it’s funny, she clarified, but because the commonplace of sexual harassment makes her uncomfortable. “It’s not even like, ‘This happened like two years ago and I’m still struggling with it.’ It’s like, ‘This is so ironically exquisite that you’re here because I need you right now.’ A lot of women have said that.”

Matt Walsh, OMMB co-founder, works at Between Friends, a nonprofit that works against domestic violence by providing services to support people experiencing abuse including counseling, teen education programs and a crisis hotline (1-800-603-4357). Since going to shows in high school, Walsh remembers seeing nonconsensual touching, particularly toward his female and gender nonconforming friends.

Kat Stuehrk, a OMMB co-founder, worked at Rape Victim Advocates (RVA), a nonprofit that supports sexual assault survivors through counseling, therapy, advocacy, and education programs. Stuehrk, who often went to shows growing up and had friends in bands in, noticed the same thing: in terms of sexual harassment and violence, not everyone feels safe in music venues and at festivals. In 2016, Stuehrk, Walsh and the two organizations began working together to address the trend of harassment they saw in Chicago’s music scene, creating the OMMB campaign. Now the campaign has over 20 volunteers.

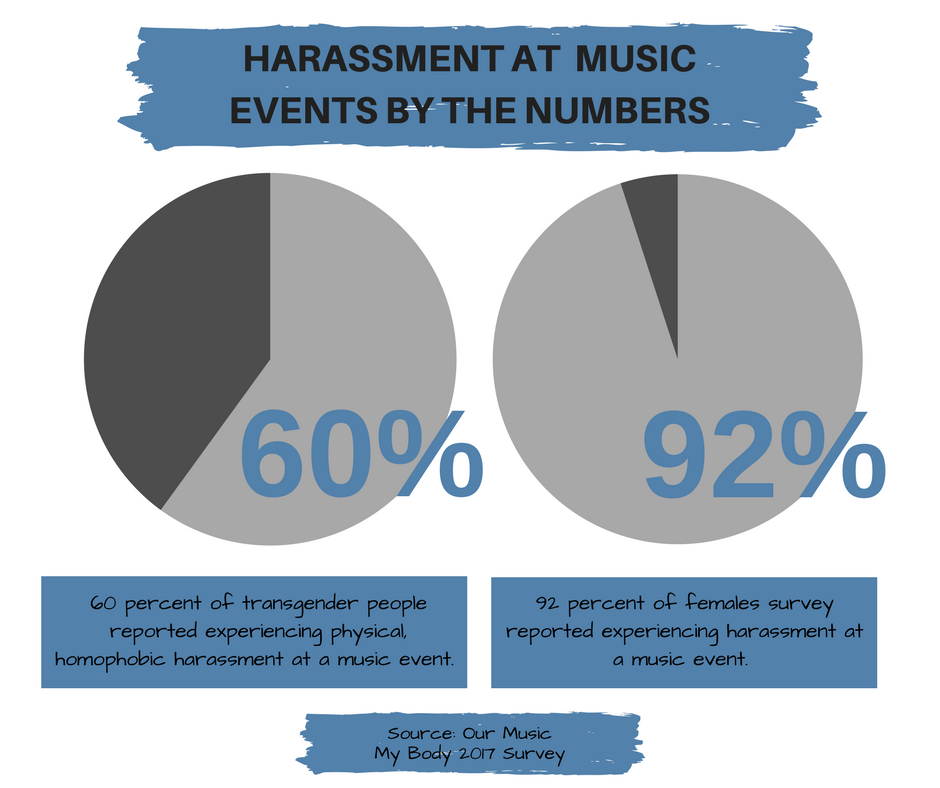

Out of 509 people surveyed at the end of 2017 by OMMB, there were 1,286 reports of harassment. That’s 2.5 experiences of harassment for every person surveyed. Harassment reported spanned from groping and sexual assault to coerced drinking and physical violence at music events. 92 percent of females surveyed reported experiencing some form of harassment and 60 percent of transgender people reported physical, homophobic harassment at music events.

(Marissa Nelson, 14 East)

However, experiences of sexual violence in the music scene aren’t unique to Chicago. Music fans around the world are speaking out about their experiences. After 11 cases of sexual assault and one case of rape in July 2017, Swedish music festival Bravalla canceled its summer 2018 event. In August 2017, Suzannah Weiss told Glamour that sexual assault was ruining music festivals for her, sharing multiple incidents of uncomfortably forward men ignoring her dissent at Belgium’s Tomorrowland music festival. In December, a man sexually assaulted a 19-year-old woman at Falls festival in Tasmania, and on New Year’s Eve at Rhythm and Vines festival in New Zealand, a man was caught on video groping a woman’s breast. Teen Vogue features editor, Vera Papisova, was groped 22 times while reporting at Coachella this year. Of the 54 women Papisova spoke with, all reported being sexual harassed at the festival.

As the Time’s Up movement continues to promote awareness of sexual misconduct across disciplines, the voices of survivors are becoming louder. Their shouts echo through the halls of Congress, studios of Hollywood and gymnasiums of athletic hubs. Now, the music scene.

In May 2017, punk band PWR BTTM member Ben Hopkins was accused of sexual assault on social media. Hopkins denied the allegations in a Facebook post in May 2017. In November 2017, indie band Pinegrove went on a hiatus amid sexual assault allegations against Evan Stephens Hall, band frontman. Hall apologized in a Facebook post in November 2017. Alternative rock band Brand New ended its European tour prematurely in November after allegations of sexual abuse and harassment against frontman Jesse Lacey arose on Facebook, including the solicitation of explicit photos from a minor. Lacey apologized in a Facebook post in November 2017. And in December 2017, indie pop artist Timothy Heller said singer Melanie Martinez sexually assaulted her. Martinez denied the allegations on Twitter in December 2017.

“Women, femme-identified people and transgender folks are experiencing gender-based and sexual-based violence at really high rates. It’s like part of the daily life experience and what’s unusual is confronting it,” said Christina Perez, an associate professor of sociology and discipline director of the study of women and gender studies at Dominican University. Rape culture — attitudes about sex that trivialize and normalize sexual violence, Perez said — is largely responsible for this. “The music scene, then, might be the epitome of that. What is going on there is certainly an expression of what’s going on in so many spaces.”

Alicia Maciel is familiar with Chicago’s music scene and the possibility of sexual harassment that comes with it. As a marketing major at DePaul University, she has promoted festivals like Riot Fest and venues like Metro and Lincoln Hall and is the manager for The Chicago Vibe, a student music media outlet. Once while attending Riot Fest, Maciel remembers a man darting his arm in front of her while she ran into the crowd, wrapping his arm around her side. She elbowed him.

“He literally did it because he thought it was fine and it wasn’t so I hit him,” Maciel said. “If he thought it was fine to touch me I literally had no problem elbowing him.”

While photographing a Freddie Gibbs show at Metro last June, Maciel said a man reached for her butt after shouting, “Where are all the white girls at,” in a crowd of mostly men and people of color. Maciel, who identifies as Hispanic, spoke with security. They kicked the man out. Aggravated by both of the men’s audacity to touch her body, Alicia shared her experiences without hesitation—as if unwanted touching and grabbing at shows happens so frequently that it doesn’t phase her anymore.

When Maggie Arthur interned at RVA, she began volunteering with OMMB. At the end of 2017, Stuehrk left RVA to study at the French Pastry School in Chicago. Though she is still involved with OMMB, Arthur took over her position at RVA and her formal role in the campaign. Arthur grew up going to punk shows in Indianapolis. She remembers being one of few girls at the shows and felt uncomfortable by the way she and others were treated.

“When I was younger, women at punk shows filled one of two roles,” Arthur said. “Either holding their boyfriends jackets in the back or trying to be one of the dudes in the front. Neither one is a great place to be.”

Women who chose to participate in the front were often disrespected by men and got pushed out of mosh pits. While this isn’t sexual harassment, Arthur points out, it is sexism. Being in the scene for a while now, she says she knows what to expect, but is still hyper-aware of her surroundings.

“I take a survey of the room and see if there are any other femme looking people there to almost position myself closer to them as a silent act of solidarity or something,” Arthur said. “So there’s always that consciousness of where are my exits, where are my people.”

Sometimes, Arthur said, she feels like she needs to act a little bit tougher. She crosses her arms against her chest and stands tall with her feet rooted to the floor so others can’t push her around. She glues her focus to the stage. At the same time, she feels like she has to watch those around her. She wonders if they will talk to her and thinks about how she will react if they do.

“Sometimes I feel like I can’t be very present and in the moment because I’m kind of trying to weigh all of those things in my brain,” Arthur said.

At concerts and festivals, it isn’t unusual for hundreds of people to stand shoulder to shoulder, squeezed into a small space. In fact, the confined environment of music shows is often thought to be a part of the experience. However, in tight spaces it is easy for unintentional touches to become purposeful and nonconsensual, Arthur said. By talking about consent at shows, she hopes to create a safer, more comfortable space for everyone attending.

“There have been instances when people have come up and been like, ‘I’m glad you guys are here because this shit has happened to me many times and I didn’t know who to tell.’ It’s not exactly a disclosure but it was just something that happened,” Arthur said. “It was just like picking up your mail — just a mundane detail that they’d had to deal with as the price of entry for going to shows.”

Developing Our Music My Body

Before OMMB was known as OMMB, RVA and Between Friends organized at Pitchfork in 2011 when the festival booked Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All (known as Odd Future), a hip hop collective Walsh said has “hateful” and violent lyrics. Pitchfork gave the two organizations a booth at the festival that year to talk about violence against women. In 2014, Walsh and a few others at Between Friends mobilized the #GetConsentAtRiotFest campaign to encourage attendees to talk about consent — or the lack of consent — at music festivals. This initiative helped jump-start the campaign in 2016 when Walsh and Stuehrk debuted OMMB at Pitchfork, distributing buttons and asking attendees to share what they think safety and consent looks like at music events.

“We are just trying to be your cool cousin to have the conversation with, to be like, ‘Hey, don’t grab someone,’” Walsh said. “Plain and simple.”

Approaching its third summer, OMMB talks about consent at shows across Chicago and works with venues and festivals to create anti-harassment statements and policies. It has worked with Lollapalooza and Riot Fest to release anti-harassment statements. However policy, Walsh said, runs deeper than hanging a sign on a venue’s wall. It’s educating staff about harassment and training them on what to do when violence occurs, which has proven to be a more difficult task for the campaign to accomplish.

“We have offered to work with any venue or festival about how they are training their staff and how they are engaging with fans if they have experienced sexual violence and we have not gotten very far,” Walsh said.

“It’s frustrating because we are literally offering up free services,” Stuehrk said. “We just want you to be able to go to a music festival and have a good time and not be worried about somebody else’s bulls**t.”

Stuehrk and Walsh hope their efforts get festival organizers to start thinking about their ethical responsibilities. Right now, the organizers seem to be more concerned about their legal responsibilities, according to Stuehrk. There are enforceable policies pertaining to drugs, alcohol and weapons at festivals, so Stuehrk and Walsh think there should be policies for harassment, too. Lollapalooza, Riot Fest and Pitchfork did not respond to multiple email requests about the OMMB and anti-harassment policies.

“It’s not an easy fix, but there’s really no excuse to not have anything,” Stuehrk said.

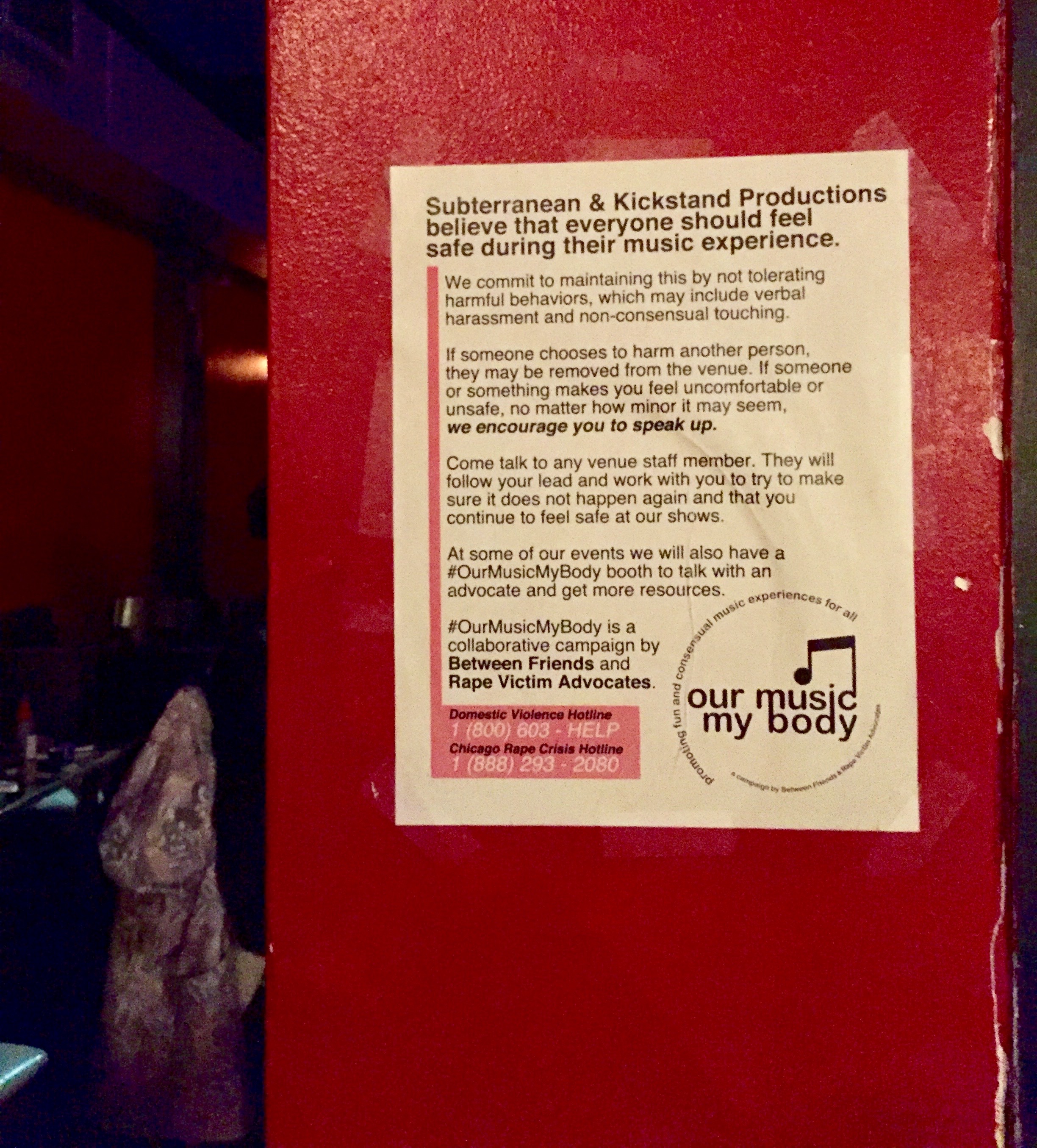

OMMB also works with local venues, particularly Subterranean, Schubas Tavern and Lincoln Hall. All three venues developed anti-harassment policies with the campaign and invite volunteers to talk about consent at shows held in their venues. Dan Apodaca is the talent buyer at Schubas. He’s been working with OMMB since September 2017 to integrate the campaign into Schubas and Lincoln Hall.

“Safety is a huge thing for us,” Apodaca said. “We are all music fans, and the last thing we would want is for someone to have anything get in the way of them getting to enjoy a show at our venues — especially something to the extent of harassment or assault or abuse because that doesn’t just ruin a night.”

Over the past six months, OMMB has begun volunteering at shows held at Schubas and Lincoln Hall. Apocada hopes the campaign’s presence encourages concertgoers to speak up if they experience harassment or assault. In the coming months, Apodaca wants to work with OMMB to create policies surrounding harassment for staff and attendees.

“Right now, we have a cover-all approach in that if you have any kind of issue please don’t hesitate to let us know and we will absolutely address it,” Apodaca said. “I think based on what we have talked about with OMMB there is a lot of benefit to having specific commitments laid out.”

Creating concrete policies pertaining to harassment at Schubas, Lincoln Hall and other venues or festivals could benefit their reputation and bottom line. 84 percent of those who responded to OMMB’s 2017 survey said they “prefer a music venue where the staff and security have been trained in violence prevention and crisis intervention.” 75 percent of those surveyed said they would “prefer a music venue with well-displayed signs that clarify the venue’s anti-harassment policy.”

An anti-harassment statement that hangs on the wall at Subterranean.(Marissa Nelson, 14 East)

What about the DIY music scene?

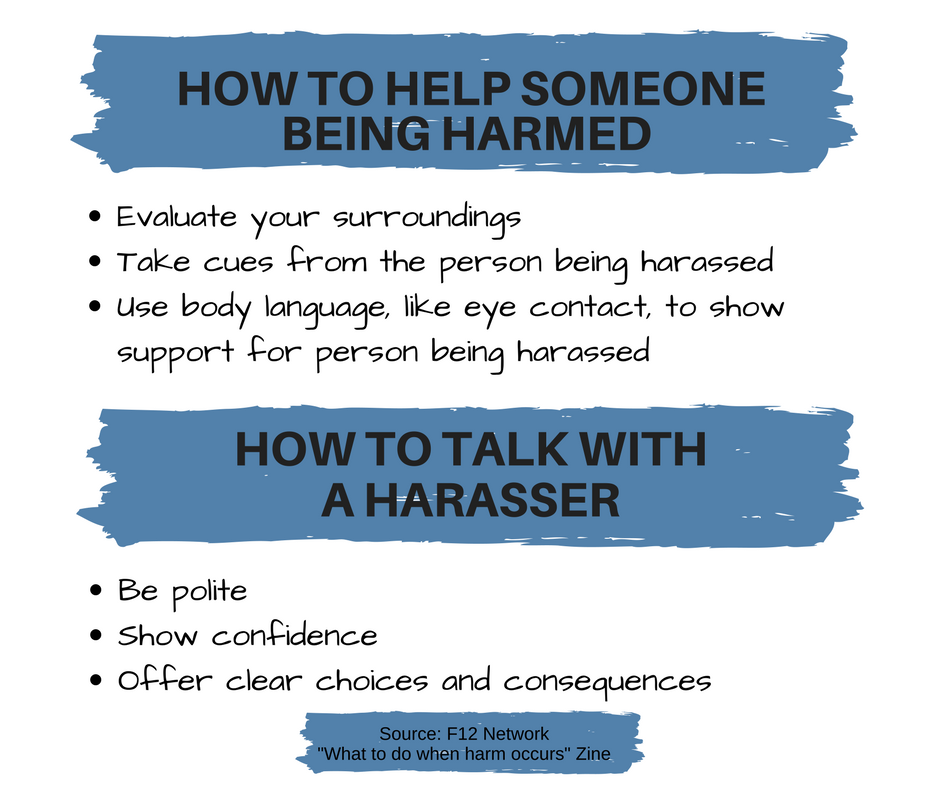

OMMB isn’t the only organization mobilizing to end sexual harassment in Chicago’s music scene. The F12 Network is a group that works to prevent sexual violence in Chicago’s art and music scenes, particularly in DIY spaces (independent venues, often located in apartments, basements and old industrial buildings). F12’s efforts formed from a desire in the DIY scene for safer environments. Instead of putting their efforts toward intervention, F12 emphasizes prevention, offering free workshops for DIY venues and organizations about conflict, de-escalation and nonviolent communication. One workshop, called Let’s Make a Plan, works with DIY venues on an individual basis. It goes through a variety of sexual violence scenarios that might occur when running a venue, allowing the DIY space to develop a response strategy specific to its location. F12 also creates educational resources such as zines, radio PSAs and posters about how to navigate and de-escalate situations of violence.

“We try to encourage venues to take up the charge themselves. We don’t try to mediate conflict,” said Sasha Tycko, an organizer at F12. “We think that conflict resolution is most effective when the people directly involved are a part of the solution.”

Until last summer, OMMB and F12 existed independently, doing complementary work in separate spaces. In July 2017, Tycko and other members of F12 spotted OMMB volunteers holding posters at Pitchfork Music Festival. Intrigued, they stopped by OMMB’s table to learn more about the campaign. Seeing similarities in the work both do, F12 invited OMMB to be a part of a campaign they were preparing to launch in the fall called #100Venues. At the beginning of 2018, OMMB kicked off its collaboration with #100Venues.

“They are on the music festival and venue level, where we work almost exclusively with DIY, grassroots or community led venues and organizations,” Tycko said. “So we’re trying to together bring this kind of sexual violence prevention work to 100 venues in 2018.”

The Conversation Extends Beyond Chicago

So Chicago has anti-harassment campaigns — what about everywhere else? In February, Bonnaroo Music and Arts festival announced on Twitter that it is working with Rape Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN) to educate festival attendees about sexual assault. Irene LaTempa, the Community Builder at Bonnaroo, said RAINN helped them create infographics about sexual assault and harassment prevention that have been shared online. The same information will be displayed around Bonnaroo’s festival grounds.

“Going forward we are exploring possible trainings on [festival grounds] with RAINN or additional leaders in sexual health, consent, autonomy, sexual assault and harassment prevention at The Well, one of our new Plazas in the campgrounds which is dedicated to all things wellness,” LaTempa said.

Bonnaroo is proud to announce that we are working with with @RAINN, the nation's largest anti-sexual violence organization, to help educate and inform all Bonnaroovians about sexual assault prevention. More details in the coming weeks. pic.twitter.com/6MrktIUMjE

— Bonnaroo (@Bonnaroo) February 9, 2018

Performers have also begun taking a stand against sexual harassment at their shows. In August 2016, Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam stopped in the middle of a song at Wrigley Field when he saw a man in the crowd harassing a woman. In August 2017, Sam Carter, Architects singer, called out a man he saw grope a woman who was crowd surfing at Lowlands Festival in the Netherlands. Drake stopped his performance while singing “Know Yourself” at Sydney’s Marquee in November when he saw a man groping a woman in the audience.

Public call-outs by performers like Drake and Eddie Vedder stand out to OMMB volunteers like Keely Brennan. She began volunteering with the campaign in January, but has been working with RVA as an advocate since 2013. At first mention she said she likes when artists take a stand in such a public manner. After a short pause, she rephrases her thoughts.

“I guess I appreciate that in a way,” Brennan said. “In another way I think it can be problematic because it also shines a spotlight on the person who is being harmed.”

Keely would rather an artist begin their show by saying they won’t tolerate harassment of any form or, if OMMB is tabling, mention their support for the campaign. This way the expectation of consent is set at the beginning of the show and unwanted attention is not brought to the person being harmed. Though all spaces should be safe, Brennan emphasized making the arts a safe space because it can often be where people turn when they don’t fit in anywhere else.

“You know we are like the Island of Misfit Toys,” Brennan said, referencing the indie and punk music scenes she grew up a part of. “We come together because it’s a place for us to belong and share an experience of music. When someone makes us feel unsafe and causes harm, we can’t participate in the same way anymore.”

How to Start The Conversation Yourself

OMMB is starting the conversation about consent with venues, festivals and audience members because harassment is not just one party’s responsibility to address, it’s everyone’s — and everyone can do something about it. Venues and festivals can develop anti-harassment statements and policies; performers can make it clear that they don’t tolerate harassment at their shows; and audience members can educate themselves on what consent looks like, how to ask for it and what to do if you or someone around you experiences harassment.

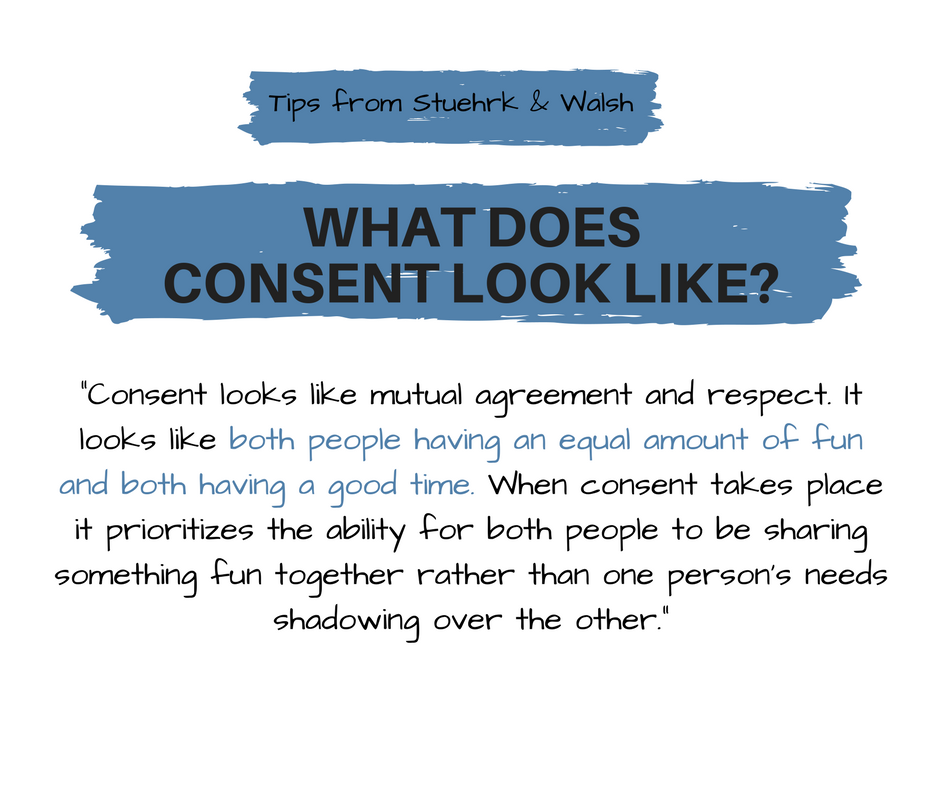

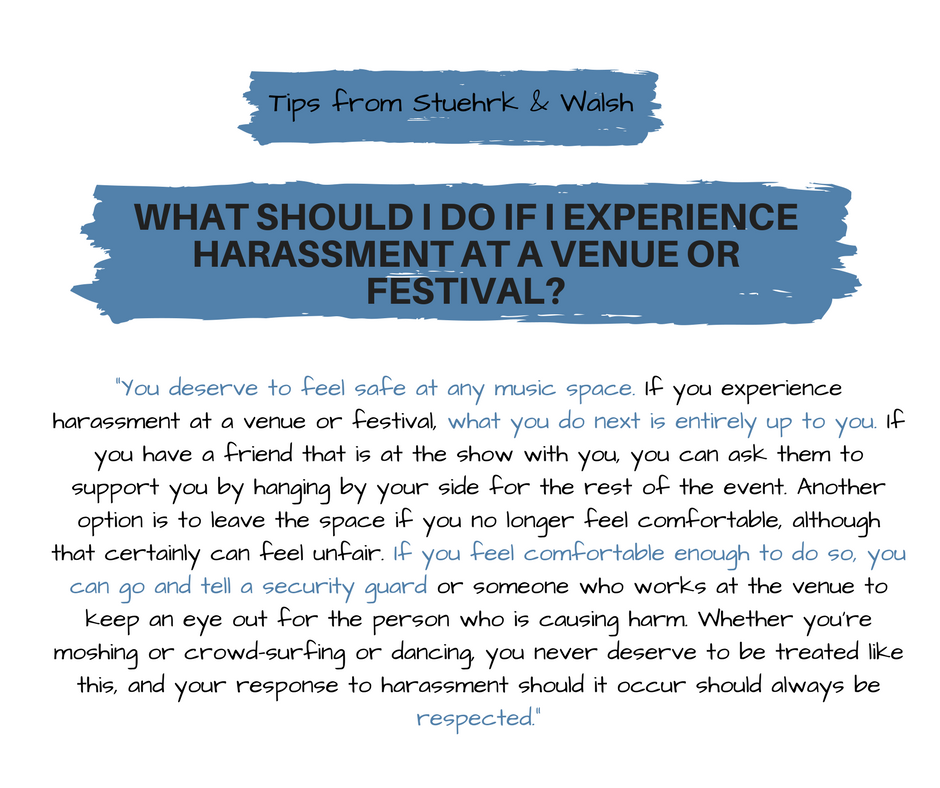

Here are a few tips from Stuehrk and Walsh:

If you’ve experienced sexual violence you can call the RAINN hotline at 1-800-656-4673 or the National Domestic Violence hotline at 1-800-799-7233 for help.

To get involved with Our Music My Body follow the campaign on Facebook or email Walsh at mwalsh@betweenfriends.org.

Header image by Cody Corrall

NO COMMENT