Cook County’s property tax assessments are shrouded in mystery — even for someone who has been studying it since the late 1970’s.

“In all the topics I covered during my time at the Tribune, nothing was as confusing as property tax assessment,” said John McCarron, journalist and expert in property tax.

When McCarron took over the urban affairs beat at the Chicago Tribune, one of the main issues he covered was property tax. He said it took a lot of on-the-job education before he could fully comprehend the methodology behind the Cook County tax assessments.

It’s no wonder that it took a long time to comprehend — not only is property tax confusing to an untrained eye, but the Cook County Assessor’s Office (CCAO) has not been completely transparent with their practices. The CCAO is the office in charge of setting value assessments for all 1.8 million properties within Cook County. Their assessments are then used to calculate the tax for every property in Cook County using the rate prescribed by the CCAO.

The assessments are supposed to be unbiased and data-driven; however, the CCAO has been embroiled in controversy ever since a Chicago Tribune report found that the assessor’s office disproportionately taxed different areas of the city. According to the report, the majority of tax reductions were granted in affluent white communities. As a result, the burden of taxation shifted —working-class communities of color on the South and West Sides of the city were being over-taxed.

The issue is a lot more muddled than one might think.

Getting political

Because the assessor is an elected office in Cook County, property taxes and how they’re assessed are often a hot button issue — and this election cycle is no exception.

“Historically, the assessor has been accused of undervaluing properties,” McCarron said. “Because it’s an elected position, you know, the assessor’s name is on the envelope and [the assessor] wants to get those votes. By undervaluing properties, he can paint himself as the good guy who doesn’t want high taxes.”

This year, current assessor Joseph Berrios was defeated in the primary by Oak Park financial manager Fritz Kaegi. Kaegi, a progressive, has run his campaign on an anti-corruption platform, pledging on his website to refuse donations from property tax firms, cooperate with Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests and increase transparency overall. This is in contrast with with Berrios, whose office shut down the Tribune’s FOIA requests for recent value assessments until a lawsuit forced the CCAO to release the information.

On a larger scale, Rahm Emanuel’s office has been watched closely for his administration’s actions related to the city’s property taxes. In 2017, Emanuel proposed a controversial property tax hike to help fund the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund.

More recently, the Cook County Clerk’s office released information which revealed that under Emanuel, nearly a third of property taxes went into special taxing districts. These taxes — approximately $660 million according to the 2018 report — go into a specific fund used to promote development and create jobs, according to the Chicago Tribune. Nearly half of this money went to special districts in affluent neighborhoods.

In the race for governor, Democratic candidate J.B. Pritzker has often been criticized for removing all toilets and indoor plumbing in his Gold Coast home — a move that resulted in a $330,000 property tax break. Months after the information became public, Pritzker pledged to repay the county for his savings.

Property taxes have become a contentious issue in the current elections, but the criticisms of the CCAO go deeper than that.

The problem at hand

For decades now, the CCAO has repeatedly come under fire for inaccurate valuations of properties, leading to both over-taxation and under-taxation as well as inconsistencies between similar properties across the county.

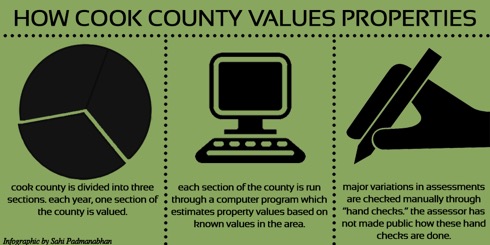

Properties in Cook County are only valued every three years, with the county divided into three sections. One section is comprised of the north and west suburbs, another of the south and west suburbs, and the last is the city proper. Every year, one section of the county is assessed, which often results a lag.

Infographic by Sahi Padmanabhan, 14 East

Additionally, properties have been undervalued in affluent neighborhoods and overvalued in working-class neighborhoods. Some properties were taxed at 120 percent of their value, according to the Chicago Tribune.

On top of the lag and inconsistency with the assessment practices, the CCAO currently uses a mainframe computer from the early 1990s to estimate property values.The computer system does not take the current market values of the homes that are being valued, nor does it use the computer-mapping system that is now standard across assessor’s offices nationwide. Officials say that the computer system is being updated, but the process will take up to six years.

As a result, the issue of regressivity, common across many counties nationwide, has been amplified in Cook County.

What is regressivity?

Put simply, regressivity refers to situations in which higher-priced properties are taxed at a lower rate while lower-priced properties are taxed at a higher rate. Property taxes in Cook County are generally regressive.

McCarron says that the issue of regressivity stems from the three-year lag in assessments in Cook County, which leads to inaccurate records of property values.

“I would argue that due to the structural problem of the three-year lag in assessments that you have a situation where declining communities are always over-assessed and communities that are gentrifying or downtown areas that are booming can be a little bit under-assessed,” McCarron said.

This structural flaw means the CCAO does not take into account rising or falling property values.

An important data point used to measure regressivity is the price-related differential (PRD), according to Daniel P. McMillen, author of “Assessment Regressivity: A Tale of Two Illinois Counties.”

The PRD of a neighborhood is calculated by taking the mean of the actual tax rates of a group of properties and comparing it to the mean of what the tax rates should be according to the assessor’s prescribed rate. A PRD of .98 or lower is considered progressive, in which higher-value properties are taxed at higher rates. An acceptable PRD is 1.03, according to the International Association of Assessing Officers (IAAO). According to these IAAO standards, anything above that is unacceptably regressive.

Chicago’s 2011 average assessment rate of 9.4 percent varied greatly from the prescribed value of 16 percent, leading to an unacceptably high PRD, according to McMillen.

Barbara Barreno-Paschall, a senior staff attorney at the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights (CLCCR), said that this high level of regressivity places an undue burden on working class and marginalized communities. One solution for individual property owners to alleviate this burden is to appeal their property tax bill through the CCAO and potentially get a reduction. But according to Barreno-Paschall, not everyone can get a reduction and the appeals in Cook County often lead to greater regressivity.

“A lot of these appeals are being filed from neighborhoods where properties are already undervalued,” Barreno-Paschall said. “There is a certain amount that the city needs to collect from property taxes, and if the reductions are being granted in neighborhoods that are already undervalued, the burden is then shifted to neighborhoods that are already overvalued.”

A history of error

A study published at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) concluded that the overall trend resulted in high margins of error across the board by the Cook County Assessor.

The 1979 study, “Relative Tax Burdens in Black and White Neighborhoods of Cook County,” concluded that there was a marked lack of uniformity in tax rates across Cook County, meaning that the taxation rate was not equal across properties of the same class in different areas of the county. Black neighborhoods were assessed at higher rates than white neighborhoods.

In 2008, two more UIC professors published a study which examined data for residential properties and also concluded that their data had a severe lack of uniformity. The coefficient of dispersion (COD), which measures the amount of variation between individual assessments, was at approximately 24 percent in 2004 and 27 percent in 2005, according to the study.

The IAAO’s recommended limit for variation is 15 percent. Cook County’s COD was too high.

In an analysis of Chicago’s tax assessments from 2011 to 2015 by the Center for Municipal Finance at the University of Chicago, it was confirmed that Cook County had consistently regressive assessments.This means the most expensive homes in the city were the most likely to be under-taxed, putting the burden of property tax onto the owners of lower-priced homes who often couldn’t afford the higher taxes.

What next?

The claim of a disproportionate burden on communities of color led to a lawsuit filed by the CLCCR.

The complaint was filed on behalf of plaintiffs Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, South Suburban Housing Center and Logan Square Neighborhood Association in the wake of more information coming to light regarding inaccurate property tax assessments. Barreno-Paschall is the lead attorney on the case.

The plaintiffs claim that the CCAO systematically and purposefully pushed the burden of taxation onto communities of color, resulting in overvaluation of properties and unacceptable levels of regressivity. The assessments under current assessor Berrios are neither uniform or accurate, according to the complaint.

The CCAO has cited a faulty statistical model as a reason for the high error rate. The model was supposed to be fixed in 2015, but the CCAO still uses the old one.

Barreno-Paschall said that something has to change, but it is difficult to know exactly what changes have to be made.

“We’re not statisticians, so we have only some ideas about the type of model that could be implemented, but what we would like to see is a system in which there isn’t 20 percent over-assessment of properties,” Barreno-Paschall said. “There should be a system in which the standards that are provided by the IAAO are followed.”

Barreno-Paschall said the ideal outcome in the CLCCR suit would be the establishment of an independent monitoring system to verify assessments by the CCAO.

The suit is currently pending a ruling on a motion to dismiss filed by Cook County.

Unclear future

“I think now that we live in the age of computers that it would be possible to have a system where when a property sells on the market place, they can input the size and value of the property so that it can be compared to other properties of the same classification throughout the neighborhood,” McCarron said.

Even that would not completely fix the issue of regressivity in Cook County.

“Inevitably, it starts getting a little subjective when really no two properties are exactly alike,” McCarron said. “Someone could fix their bathroom or put in new countertops, and their value will be different than homes without those changes.”

The use of an outdated computer compounds this issue — in the digital age, there are systems which use a combination of aerial photography, real-time data updates of market values and property maps in order to have the most accurate representation of the area being assessed. The current system does not include these tools.

Despite obvious issues in the CCAO, there is no clear solution to the problems of regressivity and disproportionate taxation. The combination of a three-year lag in property evaluations, a faulty statistical model and outdated technology makes the issue of property tax multifaceted and requires a multifaceted solution.

Header illustration by Jenni Holtz

Portfolio – Sahi Padmanabhan

4 February

[…] Regression: Cook County Property Tax Assessments Consistently Flawed […]