“Sometimes I think that this could be a fairy tale. Not the happily ever after type we tell each other to make ourselves feel better — but one of those strange, dark tales where monsters eat little children.”

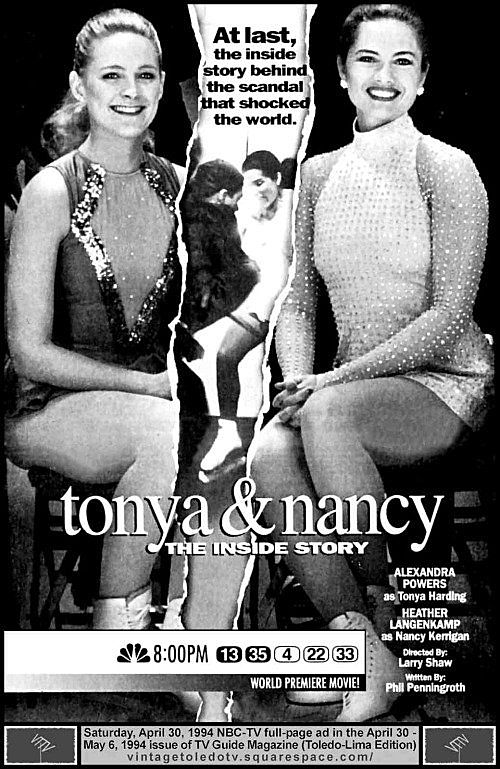

These are the first lines spoken by an unnamed screenwriter in Tonya & Nancy: The Inside Story, a 1994 made-for-TV movie about the infamous skating scandal between Tonya Harding and Nancy Kerrigan that became an international phenomenon just three months prior to its release.

The film was met with lackluster reviews, and the real life story it depicted would only get more convoluted in the months following. But while Tonya & Nancy was the first film that chronicled this moment in history — it was far from the last. Harding’s messy life and controversial decisions would become the inspiration for a countless number of reinterpretations in the 21st century — and Harding would evolve from being the most hated woman in America to a sympathetic, complicated muse.

But let’s start at the beginning.

Harding grew up in East Portland, Oregon in the 1970s. She was raised by her mother LaVona Golden, a waitress trying to make ends meet, and her father Albert Gordon Harding who took on odd jobs or was unemployed due to poor health. Money was tight and tensions were high for most of Harding’s childhood.

Harding started skating lessons at the Lloyd Center Mall at age three. When Harding started showing promise, Golden took on the role of a Kris Jenner-esque “momager.” Harding’s success was her success — so Golden paid for her lessons and hand-sewed her costumes in the hopes that she could become something bigger than their circumstance.

In retrospect, Harding describes her mother as abusive. By the age of seven, emotional and physical abuse from Golden was just something she normalized. Golden has since stated she once hit Harding on the rink out of anger, but she mostly refutes any allegations of abuse.

Harding was no stranger to abuse. In her 2008 autobiography The Tonya Tapes, Harding claims that her half brother Chris Davison routinely molested her as a child and later called the police on him after harassing her when she was 15, which led to his arrest. In an interview with Rolanda Watts, Harding said that Davison was “the only person I’ve ever hated.”

When Harding was 16, Golden and Albert Harding filed for divorce. Shortly after, Harding dropped out of high school and focused on skating full time.

Throughout the 1980s, Harding started making a name for herself in the competitive skating scene. She placed in U.S. Figure Skating Championships from 1987 to 1989, competed in the 1989 and 1990 Nationals Championships and won the 1989 Skate America competition.

And on February 16, 1991, Harding became the first American woman to land a triple axel. She won the 1991 U.S. Ladies’ Singles title with a rare 6.0 technical merit score — the first time since Janet Lynn in 1973.

Tonya Harding wins the 1991 U.S. Ladies’ Singles title. Tom Treick/The Oregonian.

Things were going great for Harding. She was winning and on a clear path to a future of success. Her talent had shone brighter than her unappealing demeanor and less than prestigious background that judges ridiculed her for. She was in control of her life and her narrative for once.

And then she wasn’t.

At around this time, Harding married Jeff Gillooly (who has since changed his name to Jeff Stone) and she found herself trapped in another web of abuse. When Harding’s career was doing well, they were happy. When it wasn’t, Stone turned possessive, entitled and violent.

“I was afraid of him, but I didn’t have anywhere else to go,” wrote Harding in The Tonya Tapes.

As she did with her mother, Harding normalized her husband’s abuse and stayed with him through potentially dangerous circumstances. She felt she had no other options, but in some way, violence was all that she knew.

“He hit me, but [my mother] hit me, but they loved me,” said Harding in 30 for 30: The Price of Gold.

Just like her mother, Stone was invested in Harding’s success. Harding was able to feed into his dream of a better life with her success but it ultimately tore them apart after she failed to medal at the 1992 Winter Olympics. Harding left Stone in 1993, but they still remained in each others lives because of the systems of abuse that consumed their relationship.

If Harding won at the 1994 U.S. Figure Skating Championship, she would garter a spot on the the Winter Olympic team and potentially $1 million in appearance fees and endorsements if she were to get the gold, which would be life changing for both Harding and Stone.

But Harding’s talent wasn’t enough — Stone wanted to ensure her win by any means necessary so that he could get the money and Harding for good. Her biggest competition at the time was Nancy Kerrigan, the previous year’s champion. Kerrigan started just as young as Harding but had every advantage Harding lacked. She was wealthy and grew up in a healthy, loving home and was much more palatable to judges and the audience at home than the brashy, rude Harding.

This juxtaposition of character was heavily used in the media. Kerrigan became the princess and Harding the trashy redneck — they were easy to categorize and thus easy to pit against one another.

And even if Harding’s technical skills were good, she would still be penalized by the judges for her homemade costumes, use of metal music in her routines and bad behavior that contrasted the image of a distinguished figure skater — an image that Kerrigan fit to a T.

So Stone paid two of his friends and Harding’s bodyguard — Derrick Smith, Shane Stant and Shawn Eckardt, respectively — $6,500 each to ensure a Harding win.

On January 6, 1994, Stant swung a 21-inch baton over Kerrigan’s right knee. Later dubbed “the whack heard ‘round the world,” the impact forced Kerrigan to withdraw from the championship and her title.

Two days later, Harding won the Ladies Championship title and a spot on the Winter Olympic team. Kerrigan, even though she was unable to compete, was also selected for the team.

The following week, the FBI began an investigation on Kerrigan’s attack. Eckardt confessed to the FBI and implicated Harding, Stone, Stant and Smith. Eckardt and Smith were then arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit second-degree assault. Stant, who went to his home in Phoenix, Arizona to flee, was caught and he surrendered to the FBI.

Throughout all this, Harding was still training for the Olympics like nothing had happened. Everyone thought she did it, or helped orchestrated it, or at least knew about the plan at some capacity. Trashy Tonya tried to ruin sweet, precious Nancy’s career. It perfectly fell in line with what the public already believed about each of them.

“I’m for Tonya. What about you?” Katha Pollitt wrote in her 1994 column for The Nation. “You have to like a woman who gets reamed out by prissy sports-writers because she smokes, peroxides, wears loud nail polish and teeny tank tops, and says she wants to win a gold medal at the Olympics for the money.”

Because of the controversy, Harding was unlikely to receive any of the lavish endorsement deals she expected. But she still skated. She didn’t want the money anymore, she was there to prove herself to everyone who doubted her. She wanted to win.

Tonya Harding practices for the 1994 Winter Olympics. Photo: Andrew Parodi, CC 2.0.

On January 31, 1994, Stone stated that Harding approved the Kerrigan plan. He later pleaded guilty to racketeering for a 24-month sentence. Gillooly’s attorney accused Harding of conspiracy after a restaurant owner found Stone and Harding’s trash and gave it to the FBI. The trash revealed incriminating notes allegedly in Harding’s handwriting, which included the phone number of Kerrigan’s practice arena along with her training times.

Harding sued the U.S. Olympic Committee in attempts to stop a planned hearing to decide whether or not she should participate in the Olympics. Harding ultimately dropped the lawsuit and the committee canceled the hearing — Harding was allowed to skate in the Olympics.

Kerrigan won the silver medal at the 1994 Olympics and Harding, still under investigation, placed eighth after one of her laces breaks. It was the third highest rated sports event in television history at that time.

In March, Harding went back to Portland and plead guilty to conspiracy to avoid further prosecution. She was sentenced three years probation, paid $160,000 in fines and resigned from the U.S. Figure Skating Association. In June, Harding was banned for life from the U.S. Figure Skating Association and was stripped of her 1994 national figure skating title.

Harding remained in the limelight for better or for worse. She managed wrestlers Eddie Guerrero and Art Barr and even became one herself, returned to skating while angry audience members booed and threw batons on the ice, did various high profile (and paying) interviews and even placed third on season 26 of Dancing With the Stars.

Poster for Tonya & Nancy: The Inside Story.

But what is truly remarkable is how this story of someone so publicly hated and villainized has become the inspiration of several contemporary works, most of which see Harding as a sympathetic, misunderstood heroine.

In 2008, Tonya and Nancy: The Rock Opera premiered in Portland and later toured in Los Angeles, New York and Chicago. The show is a dark comedy based on the events of the Harding story. “The story is in a sense beyond satire, since the level of absurdity and melodrama in the real events is already so high,” according to the show’s website. Harding even went to a performance. “She got onstage and said everyone here deserves a big applause,” Elizabeth Searle told The New York Times.

In 2014, the Harding story was turned into a full comedy in the form of Tonya Harding: The Musical written by Jesse Esparza and Manny Hagopian. The United Citizens Brigade Theater hit characterized Harding as a woman sick of her lousy husband and being forced to share the spotlight with goodie-two-shoes Kerrigan.

Also in 2014 was The Price of Gold, part of ESPN’s 30 for 30 series which focused on Harding’s issues with class in a sport that reeked of the elite.

In 2017, Dan Aibel’s play T. told the Harding story without Kerrigan at all. Kerrigan was referred to as “Horseface” by the characters but was never on stage — further feeding into the narrative of Harding being a misunderstood dark horse.

The most notable fictionalization of Harding’s life was the 2017 film I, Tonya which similarly saw Harding as an unlikely and unlikable hero attempting to overcome her circumstance tooth and nail. The film is based on “irony free, wildly contradictory, totally true interviews” with the story’s key players — and Harding (Margot Robbie) never lets the audience put the blame solely on her.

The film garnered Allison Janney acclaim for her portrayal of Golden at the Oscars, Golden Globes, Screen Actors Guild Awards, BAFTAs, Critics’ Choice Awards and the Independent Spirit Awards. Margot Robbie was also recognized for her portrayal of Harding at the Critics’ Choice Awards and AACTAs.

“America…you know they want someone to love, but [they] want someone to hate,” said Harding at the final scene of I, Tonya. “And they want it easy. What’s easy?”

And there is something so uniquely American about Harding’s story. Regardless of how one feels about Harding or whether or not one believes she had something to do with the attack, Harding couldn’t care less. She wanted to make a name for herself and she did so in a way that was truly her own. She was known not just for her skating prowess, but for her very persona — one that was entangled in the various complexities and contradictions that made up her life. Everyone has an opinion on Harding, but when it comes to a lasting image — Harding has the gold.

Header image by Andrew Parodi, CC 2.0.

NO COMMENT