This piece was adapted from an episode of The Radio DePaul Podcast published in 2017.

It’s February 14, 1929, and seven members of the Irish-American North Side Gang have been lured into a warehouse in Chicago by the infamous gangster Al Capone. After being ambushed by Capone’s men, the seven Irishmen are lined up against a wall and raked by machine gun fire.

This event rocked Chicago — but the loudest shot came several hours after the guns stopped firing. The shot that rang through time came from the camera of Jun Fujita, whose photograph of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre galvanized the city against organized crime.

Fujita was the first Japanese-American photojournalist, but his work as a poet and actor, as well as local celebrity-status in Chicago, has created a sort of legend around him. This legend has attracted a number of people to study Fujita, including myself.

Inspired by his photography and poetry, Fred Sasaki and Katherine Litwin curated “Jun Fujita: Oblivion,” an exhibition dedicated to Fujita’s work at Chicago’s Poetry Foundation in 2017. Two years after the success of this exhibition, they published a catalog under the same name earlier this month.

“There was a sort of legend about him, of always being first on the scene. Sometimes inexplicably so,” said Sasaki. “For example, on the occasion of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, people just couldn’t understand how he arrived there so fast, and he was the first one to shoot it.”

The aftermath of the massacre was one of many tragedies Fujita was known for documenting as a photojournalist at the Chicago Evening Post, but what catapulted him into the town’s high-society was his status as the go-to photographer for celebrities. He captured Carl Sandburg, put Albert Einstein to film and even shot Al Capone himself.

Carrying the stories of Fujita more than 50 years after his death is his great-nephew Graham Lee, author of the upcoming biography Jun Fujita: Behind the Camera. Lee has become the one of the principal sources for those looking to understand Fujita, along with Sasaki and Litwin.

“He almost, for me, is like this great Samurai figure,” said Lee. “He’s larger than life, he’s alone, he’s got this mission, he’s fearless, he’s mysterious. All those kind of qualities just make him more intriguing and the more I unveiled the layers and looked at this man, he just was such a fascinating character. It just made you want to be a part of his life.”

Sasaki recounted a Fujita anecdote he had learned from Lee: “there’s this story that Al Capone drove alongside him at one point and said ‘Hey! I heard you’re good with a knife, how about you join up with us?’ and Fujita replied, ‘I’m better with a camera.’”

Photo of the Indiana Dunes by Jun Fujita. The Dunes were a particular place of interest and inspiration for Fujita. Courtesy of the Graham and Pamela Lee private collection.

As Litwin said, Fujita was a Renaissance man in 20th century Chicago. He loved speed and motorboats, he was a brilliant cook who would host feasts for the grand personalities of Chicago like architect Spencer Cone and homicide detective John Higgins and he was a poet who would spend days studying nature for his Japanese-style Tanka poems.

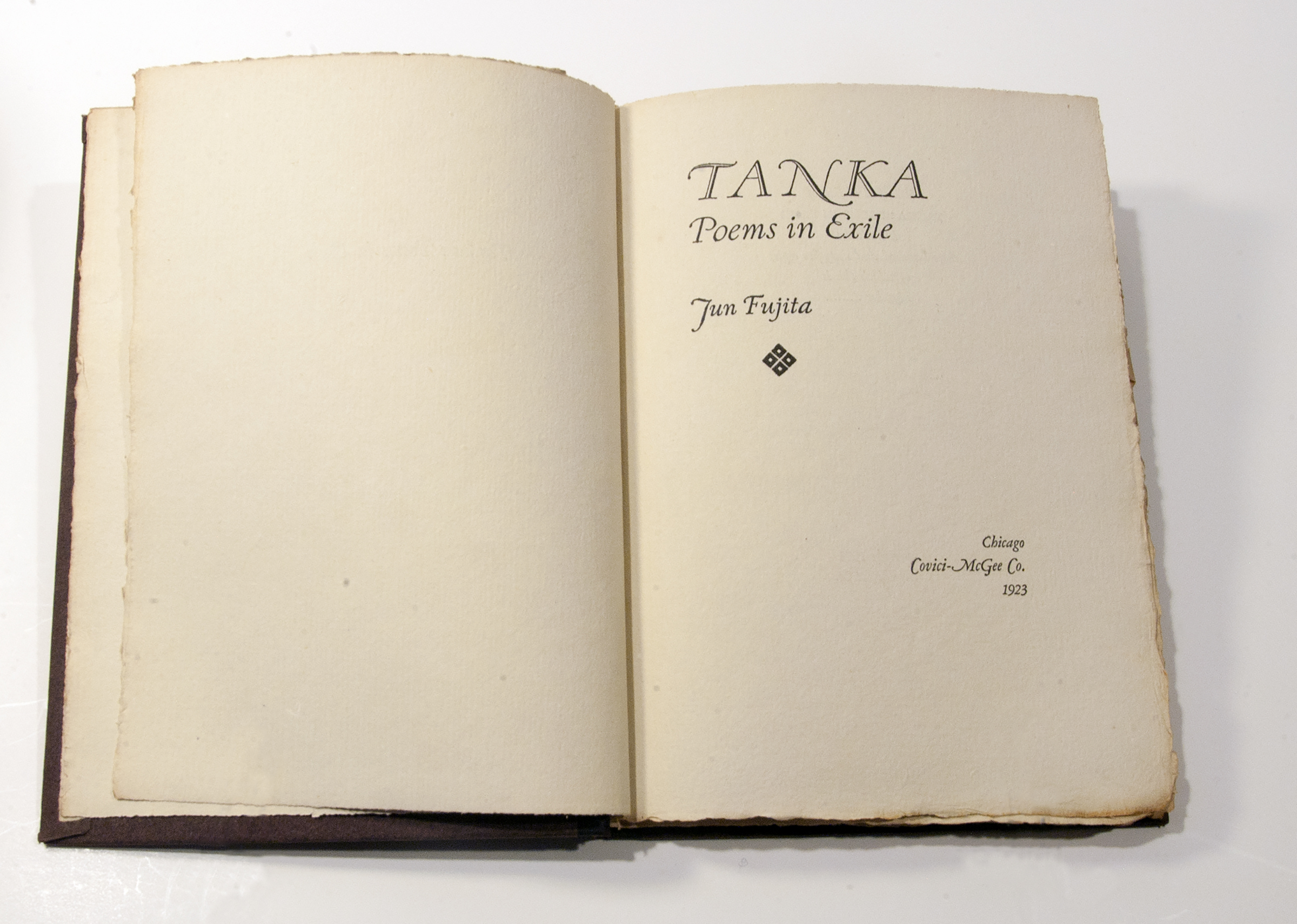

Poetry was what Fujita considered to be his true profession, though he only ever published one collection in his lifetime. Writing them throughout his life, he felt his poems captured the mood and emotion of the natural world in a way his photos could never match. He would spend months working on a single poem with only three lines and he’d change minute details years after finishing the poem. According to Lee, Fujita would go through copies of The New Yorker and scratch out poems he thought were “unworthy” of being published.

“When you look at his writing, for me it really is so distilled that you don’t get a sense of his grandiose personality, but maybe it’s sort of a microscope into this inner mood which he carried,” said Lee.

“I kind of liken it to how he’s pictured at parties. So here he’s invited celebrities of the time to his house and he’s cooking for them, he’s playing classical music and to everyone it’d feel like it’s sort of a big deal. It’s pretty loud there, people talking over each other, but Jun was probably pretty quiet. From what I’ve heard he’d sit there and just absorb everything around him. Finally the room would fall quiet and he’d speak, and to everyone it’d be like ‘Woah, there’s what Jun said, we’ve been waiting for him to finally comment on this.’ and I think that sort of feeling is what his poetry feels like. It’s that really thoughtful, observational mood that comes through when he looks at nature.”

“Tanka: Poems in Exile,” the only poetry collection Fujita published. Courtesy of the Graham and Pamela Lee private collection.

Fujita broke down barriers as a Japanese-American, but he was still affected by the rampant racism of the 20th century. From the moment he emigrated to America in the late 1890’s, Fujita was followed around by FBI agents and constantly had a large hunting knife and a gun holstered under his arm as a result. He barely avoided the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II because, according to Lee, he was pulling in favors from the newspapers and important friends of his in Chicago, most notably his former boss Michael Straus, editor of the Chicago Evening Post.

Despite the ever-present feeling of danger, Fujita still offered his services to the government. “In both world wars he reached out to the government and said, ‘Here’s who I am, can you use my services in any way, how can I help?’ and each time he was rejected,” said Lee. “I think it helped to impress others that he was an American first. He held the country dear to him and he was willing to serve if needed.”

This idea of “testing” immigrants is part of what inspired Litwin and Sasaki to curate “Jun Fujita: Oblivion,” at the same time as the United States began enforcing an executive order banning travel from several Muslim-majority countries.

Perhaps the strongest racism Fujita experienced came in the form of his personal life. Fujita was in love with a white journalist named Florence Carr, but they chose not to marry until decades later. The two never had kids, fearing the injustice that may be inflicted on a biracial child.

Fujita and Florence Carr at the Indiana Dunes. Courtesy of the Graham and Pamela Lee private collection.

Lee still struggles to reconcile with the two sides of Fujita. On the one hand, he was an engineer, a mathematician and a workhorse in his photography. On the other hand, he was “this deep soul who was looking for poetry, for these small little tanka poems that speak with a deep voice that bloom and grow the more you read them.”

“I think in one sense there’s a little bit of sorrow and heartbreak because when you look at it, there’s really these tragic events that he captured,” such as the sinking of the SS Eastland in the Chicago River and the 1919 Race Riots. “All those things just cut him to the quick. Those were heartbreaking events to capture and it was his job to be there and capture that. Obviously it was just heartbreaking for him, and maybe that fueled his need to resolve that through his poetry.”

On February 1, about 30 people gathered at the Japanese American Service Committee in Chicago to celebrate the launch of the “Jun Fujita: Oblivion” catalog, as well as to hear from a panel of Fujita scholars like Lee, journalist Takako Day, DePaul University professor Nobuko Chikamatsu, as well as Litwin and Sasaki.

Chikamatsu found this gathering of different people interested in studying Fujita to be incredibly helpful. “We can bring each of our strengths and knowledge together so we can find out more, and that’s wonderful,” said Chikamatsu.

After studying Fujita, Chikamatsu believes he represents something hopeful for first-generation immigrants. “I think for many of us, there’s this experience of being kind of a misfit in our own native community,” she said. “But [I] was given the opportunity to study and graduate here, and I can never thank enough for that. That’s why I’m teaching now at DePaul.”

“I think we are misfit[s], but the U.S. kind of saved us and gave us opportunity and I think Jun was somebody like that,” said Chikamatsu. “He really broke this stereotype of what Asian-American could be.”

The catalog launch was full of celebrations and discussions of Fujita’s life, as well as new discoveries from the convergence of different experts. For instance, Lee says that Fujita always claimed to be the descendant of a samurai family. As a Japanese-American, Sasaki said his family also had this personal legend. Once Day heard about this, she took a look at Fujita’s birth certificate and confirmed to the two of them that he absolutely was not a samurai. According to Lee, it’s unclear why this myth was perpetuated or if Fujita himself even played up the stereotype. But for some reason he allowed the legend of the “Samurai Fujita” to persist.

Fujita was a man of contradictions. He destroyed the perception of what a Japanese-American was and wasn’t able to accomplish — and he was punished for it with discrimination rooted in fear. He was famous for his photography, yet shunned it in favor of poetry. He was beloved by his adopted city but eyed with suspicion by his adopted country.

Widespread knowledge of Fujita may have faded from history, but the memory of him remains in those attracted to the magnetism of the man who shot Capone.

The Poetry Foundation recently published a catalog entitled “Jun Fujita: Oblivion” featuring works shown in the 2017 exhibition.

Bombs, Ghosts and Bus Tours: The Dying Gasps of the Chicago Mafia – Fourteen East

25 April

[…] on it skirting around town, or been to Chicago’s macabre mafia tourist sites like the site of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre on the North Side or outside the Biograph Theater where John Dillinger was […]