At my Catholic grammar school, we had morning prayers and announcements over the PA system every day. The routine was normally a scripture reading, reflection questions, a religious song and then the morning announcements. I walked into school on the first day of Black History Month and saw so many faces that looked like mine and my classmates. The walls were covered with paintings and photographs of prominent Black figures who impacted the world in their fight for liberation. That morning was like every other morning; I zoned out of the scripture reading and I recited the prayer as if it was muscle memory, but the song of that day was different. I heard the familiar voice of my older cousin leading the song, “Oh Freedom!” over the PA system.

No more mourning, no more mourning, no more mourning over me

And before I’d be a slave I’ll be buried in my grave

And go home to my Lord and be free

Blackness, music and revolution are bound together by Black oral tradition. Music is an Africanism or an integral part of all cultures of the African/Black diaspora. Music was — and still is — used to tell stories, share information or pass down traditions from generation to generation.

Later on that month, my school held its annual Black History Month Celebration. The kindergarten through eighth grade classes had to perform some expression of staged art to commemorate the work of Black people. At the beginning of this ceremony, my third grade teacher lead us in a song we all seemed to know by heart.

Lift every voice and sing

‘Til Earth and heaven ring

Ring with the harmonies

Of liberty

Known by many as the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was written as a poem by author and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson, then later put to music by his brother, John Rosamond Johnson. The lyrics convey a sense of reflection on the past, while looking forward into a potentially bright future.

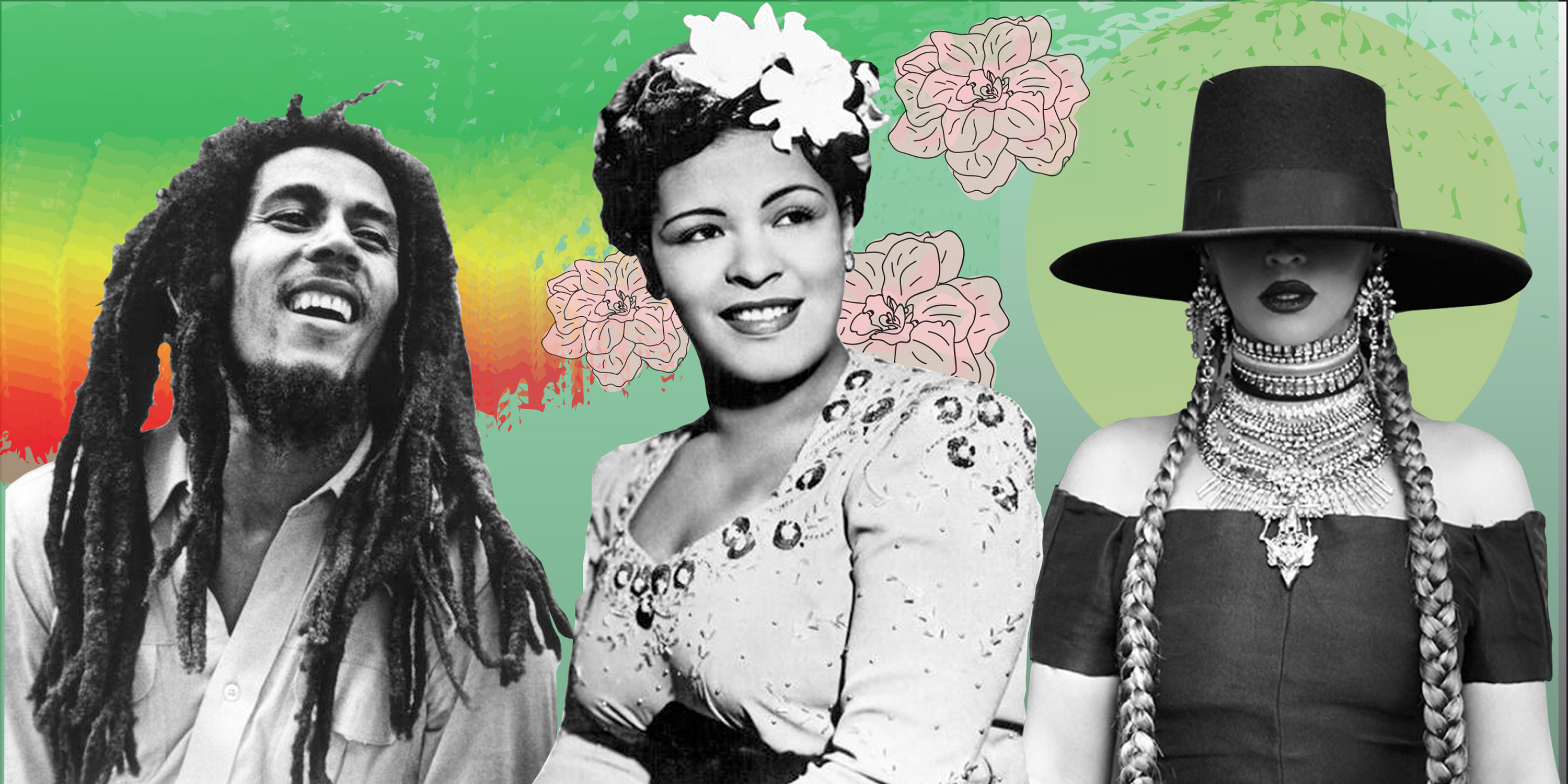

Similar to “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the political song “Strange Fruit” started as a poem. “Strange Fruit” was created as a reaction to the influx of racialized attacks in the United States. Racialized violence in the United States mostly revealed itself through lynchings. From 1882 to 1968, 4,743 lynchings were recorded and over 85 percent of those victims were Black. However, it is important to keep in mind that lynchings and other forms of racialized violence often went unrecorded, so these numbers were likely much higher. Contrary to the victim demographic, Abel Meeropol, a white Jewish man, wrote the poem that sparked the musical rendition, which was composed by his wife. Billie Holiday was performing at Cafe Society when Barney Josephson, the founder of the club, presented the song to her. What followed was later considered Time Magazine’s Song of the Century.

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Later covered by Nina Simone in 1965, the power of the song and the pervasiveness of racialized violence continued to impact Black Americans.

Musically, James Brown entered my life through HGTV soul music box sets. A song I never heard sung in an inside voice makes it back into my mind whenever I needed it the most.

Say it loud: I’m black and I’m proud!

Say it loud: I’m black and I’m proud!

The power in saying — no — shouting, exclaiming the lyrics, “I’M BLACK AND I’M PROUD!” is a huge slap in the face to racism. Taking pride in something that has been demonized, in something that people have built entire structures against, taking pride in the counter-narratives of Blackness, is revolutionary.

Every Sunday, my parents would fill the house with reggae music. The lyrics of Bob Marley would reverberate through the house for hours. Marley has a hefty discography, most of which reflect only an aspect of the Black experience. “War,” a song Marley adapted from Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie’s 1963 speech to the League of Nations regarding Benito Mussolini’s siege of Ethiopia, always gave me chills. The combination of the words of the speech and the heavy reggae influence combine two worlds. It made separate struggles feel universal.

Until there no longer

First class and second class citizens of any nation

Until the color of a man’s skin

Is of no more significance than the color of his eyes

Me say war

Conceptions of Blackness tend to be static. Situating Blackness solely in the United States isolates the global realities and repercussions of life as a Black person. Marley, along with other reggae artists, gives a voice to the Black diaspora in the Caribbean.

My freshman year of college, I was ranting about how so many Black movements isolated Black women and queer folx. After taking some classes and doing intense reading, I discovered the world of Black feminism. Intersectionality, a concept coined by Kimberle Crenshaw, interrogates the way multiple marginalized identities function in creating a specific experience under systems of oppression. In the same year, Queen Latifah released her single, “Ladies First.” Latifah, along with London rapper Monie Love, emphasized the role of Black women in different facets of their lives.

Who said the ladies couldn’t make it, you must be blind

If you don’t believe, well here, listen to this rhyme

Ladies first, there’s no time to rehearse

I’m divine and my mind expands throughout the universe

Beyonce’s release of Lemonade, closely followed by Solange’s release of A Seat at the Table, left me shook beyond repair. Visually, Lemonade left an impact on the realm of Black aesthetics. The song “Freedom” felt too familiar on my first listen.

I’ma wade, I’ma wade through the waters

Tell the tide, “Don’t move”

I’ma riot, I’ma riot through your borders

Call me bulletproof

“Wade in the Water,” a popular Negro spiritual, emerged during the Underground Railroad. The song describes the journey enslaved Black people took to freedom. Beyonce’s nod to Negro spirituals brings the journey towards liberation full circle.

On September 30, 2016, I cried through my first listen of A Seat at the Table. Solange was able to convey every emotion I couldn’t verbalize, let alone write a whole album on. The album seamlessly combines the pro-Black confidence of “I’m Black and I’m Proud,” while centering the intersectionality presented in “Ladies First.” Alongside her striking lyrics, the interludes strengthen the album’s impact. The aesthetics during this era solidified Solange in a league of her own, while simultaneously amplifying different depictions of Blackness. The track “F.U.B.U.” is titled after a Black owned fashion company. The abbreviation stands for “For Us By Us,” and that is the energy that is conveyed in the song.

When you feeling all alone

And you can’t even be you up in your home

When you even feeling it from your own

When you got it figured out

When a nigga tryna board the plane

And they ask you, “What’s your name again?”

Cause they thinking, “Yeah, you’re all the same”

Oh, it’s for us

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The sense of community in “F.U.B.U.” reflects the Black experience. The negative and positive experiences we have is something specific for us. The song highlights the specificity and uniqueness of the Black experience.

Black music’s conjunction with revolution goes way back. Like, way before Tidal, Spotify and Apple music were even thought of. The presence of music in the never ending journey for Black liberation has been a key part of its history. The shift in my life from being the child who listened to her elder’s music to the elder with the great music taste has been interesting. The eight-year-old girl hearing and loving historical songs has evolved into a playlist junkie who combines different genres and time periods to elicit a specific set of emotions. Hopefully, this playlist brings back memories of your favorite family member or has songs can be used as words of affirmation.

Black History Month: It’s The Most Wonderful Time of the Year

A playlist converted by Soundiiz from another music platform ! https://soundiiz.com

Header image by Natalie Wade

NO COMMENT