Think of jobs people can extract a whole career from and it’s natural to be drawn to the trades — plumbers, electricians, mechanics — unless you’re thinking of Chicago. Here, politics is a trade, and some on City Council have made careers out of a four-year job.

The longest being that of Edward M. Burke, alderman of the 14th Ward, dean of the city council and the 35th alderman to face corruption charges since the 1970s. For 50 years Burke has represented the 14th, making him the longest serving alderman in Chicago history by a full term — history that wouldn’t have been made if he were living somewhere else.

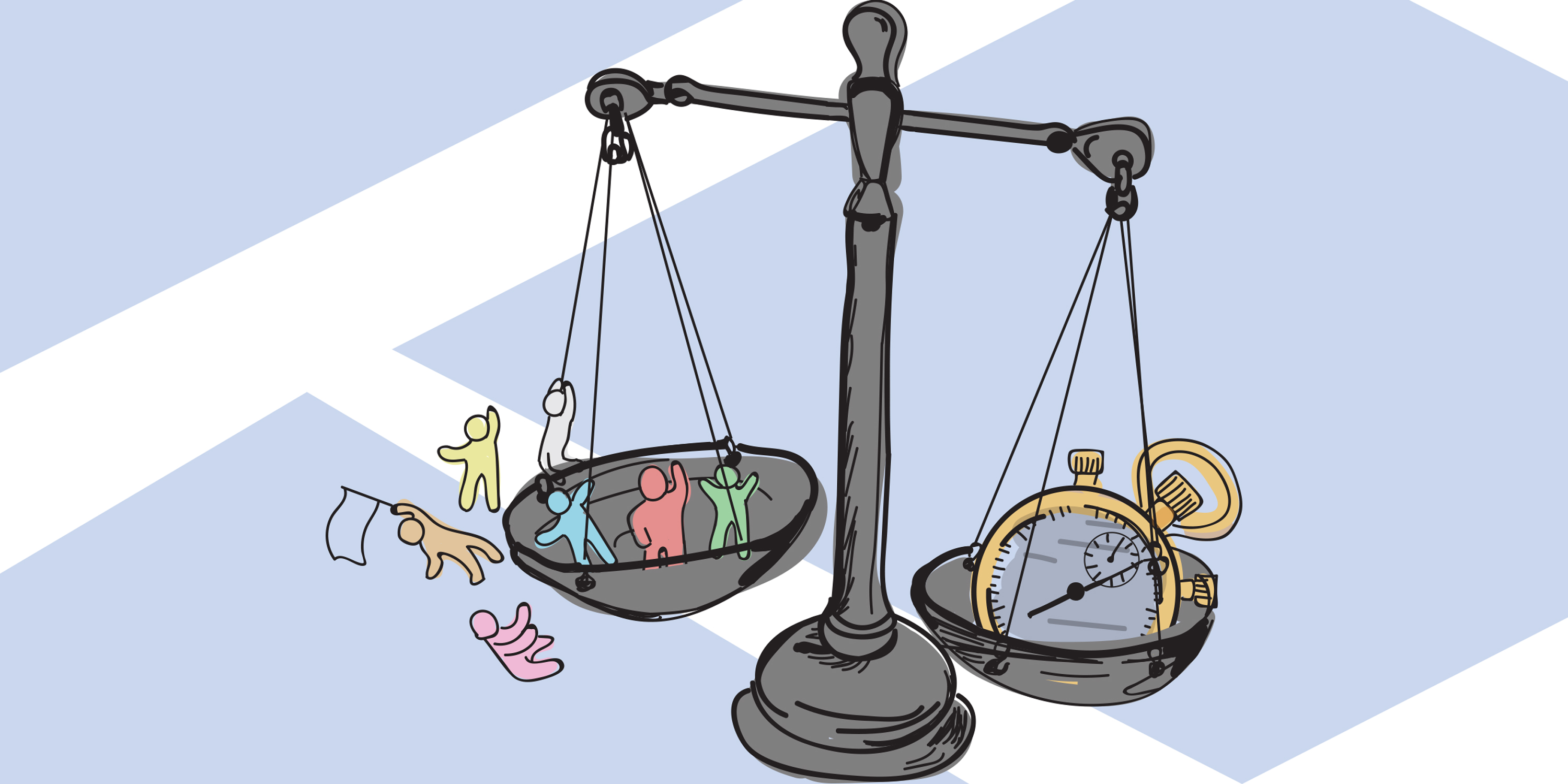

Unlike other major cities like Phoenix, New York City and Dallas, Chicago does not subject its council members to term limits. Instead, aldermen can serve for as long as they want — so long as they are elected.

Chicago’s aversion to term limits has allowed aldermen to preside over their wards for decades, and with the city’s history so steeped in corruption, this unlimited tenure has the ability to push elements of our dark past into the present.

Today, 30 percent of Chicago’s aldermen have served on the city council for at least 15 years — and six, including Burke, have been there over a quarter of a century.

While efforts to establish term limits for the mayor and Illinois state representatives receive bipartisan support, many in Chicago’s city council are settled in for the long haul. But with 11 suburban communities in Cook County now embracing term limits for their officials, can that momentum shift toward Chicago?

Outgoing alderman and current candidate for Chicago Treasurer Ameya Pawar seems to think so. In 2011, Pawar was elected to represent the 47th Ward, taking over a council seat previously held by longtime Alderman Eugene Schulter. Shulter was elected in 1975 at the age of 26 and maintained that same position throughout the bulk of his working years.

In direct contrast with his predecessor, Pawar has committed to a self-imposed, two-term limit and remains so even after receiving over 80 percent of the votes in his ward’s 2015 election.

With that 30-point jump from his first term, Pawar clearly found some recipe for success in his ward. Sticking around could have even spared his constituents in the 47th from the nine-candidate race to replace him. Leaving, however, does fulfill his wish to “bring a fresh set of eyes and ideas to this office.”

Although Pawar is vying to remain in city hall as city treasurer, his two-term policy feels like an unfamiliar concept in a council with over half of its members seeking a third term or beyond.

Granted, it’s not too difficult to understand why people stay. Despite being the first point of contact for public grievances, Chicago’s most powerful part-time job offers a six-figure salary, generous pension and a voluntary cost-of-living increase. There are also no laws barring council members from holding down certain jobs in the private sector, like 44th Ward Alderman Tom Tunney’s several Ann Sather restaurants or Burke’s recently raided law firm.

Still, it’s a privilege Chicago’s council members have been exploiting since the waning years of the Gilded Age, with the most colorful example coming from John “Bathhouse John” Coughlin — number two on the list of longest-serving aldermen. Along with Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna, Coughlin hosted the First Ward Ball — a political fundraiser started in the late 19th century known for uniting prostitutes, police and politicians alike. The pair, referred to as the “Lords of the Levee,” ran Chicago’s red light district in tandem with their legislative duties before police shut it down in 1912.

Despite Coughlin’s reputation and the closing of the Levee, he was reelected to the city council a total of 19 times. While he ran the 1st Ward in a scarcely-regulated, expanding Chicago, it’s an interesting daydream to wonder how the city would have fared if he gave up his seat after two or three terms.

But with Pawar leaving this year, we now have some broad idea what a distinct, controlled beginning and end could look like in the city council. As alderman, Pawar helped pass an ordinance protecting single-room-occupancy hotels, worked with Mayor Emanuel on TIF reform and was co-chair on the panel that crafted the paid sick leave ordinance.

While Pawar now has his sights set on another position in city hall, his two-term limit did not make him completely immune from indulging joining his long-serving peers — at least when it comes to attendance.

In a joint analysis from WBEZ and The Daily Line, Pawar, along with veteran aldermen Patrick J. O’Connor, George Cardenas and Carrie Austin, have a city council attendance rating under 50 percent.

“I’m proud of my record and I personally don’t know that it makes a whole lot of sense to be voting on every single sidewalk cafe, stop sign, every minor adjustment that we make, and so I’ve been on the record of that,” Pawar said to The Daily Line and WBEZ.

Attendance aside, the lack of term limits on the city council have helped turn some aldermen into pension millionaires. According to an Illinois Policy report from July 2018, four aldermen have collected over $1 million in pension payments and 15 currently receive over $100,000 of taxpayer-funded money per year.

Pension laws allow aldermen to receive maximum benefits after 20 years of service — roughly 10 years faster than other participating city employees. Other workers also stand to make just 70 percent of their final pay, compared to 80 percent for those on the council.

One person interested in shaking up the city council is directly related to the mayor that helped pass the 1991 plan responsible for this. Bill Daley, mayoral candidate and brother to former six-term Mayor Richard M. Daley, wants to shrink the city council from 50 to 15, bar members from having other jobs and cut them off after three terms.

Whether Daley wins or not, Chicago residents will still be served by a city council in flux — with two aldermen under federal investigation and an uncertain mayor’s race with 14 candidates. What is more certain, however, is that the ten largest cities in the U.S. have all adopted term limits — except for Chicago.

Header image by Natalie Wade

NO COMMENT