Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez might not have been where she is today without the movement at Standing Rock. Three years later, and the spark we saw in North Dakota is still burning today. We have a handful of new and young politicians pushing a Green New Deal, two of the first Native American Women elected to congress and water protectors around the country who are still working to protect what is sacred.

In 2016 and early 2017 there were many demonstrations in the Standing Rock Indian Reservation against the Dakota Access Pipeline. People came from all over the world to stand with Standing Rock. These water protectors, not protesters, because that often has a negative connotations, gathered, some for months on end, to defend the land and water. This pipeline, originally supposed to be routed through Bismarck, North Dakota, a predominately white city. The city rejected the pipeline, and then it was rerouted to go under the Missouri River and Lake Oahe, which threatened access to clean water to everyone downstream. The Missouri River, as well as Lake Oahe, is the main clean water resource for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. As well as threatening access to clean water, it was also intended to be built over ancient burial grounds. While Obama eventually rejected the Dakota Access Pipeline, Trump’s presidency was so close on the horizon that as soon as he took office he approved the continuation of the pipeline. It was eventually built, and the pipeline leaked at least five times in the first six months of use.

The movement that started at Standing Rock ignited a flame within me. It mobilized me in a way that nothing else ever has. I remember almost failing many of my classes my sophomore year, because I was protesting and organizing every day instead of going to class. The fight then continued in the Bayous of Louisiana with the tail end of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which intended to rip through the fragile wetlands of Louisiana. This was a very rare instance where my indigenous identity directly intersected with my New Orleanian identity, and this just mobilized me more.

My family is Listuguj Mi’qmaq First Nation, which is located in Listuguj, Quebec. Many of my relatives live on the reserve, and as I’ve continued to connect with other Mi’gmaq people, there is a common phrase that constantly grounds me. It is translated throughout many indigenous languages, in Mi’gmaq, the phrase is “Msit No’Kmaq,” which translates to “All my relations.” The spirit of all beings, plants, animals, water, are all related. One of my new favorite podcasts is All My Relations. It’s hosted by Matika Wilber (Swinomish and Tulalip) Adrienne Keene (Cherokee Nation) who talk about contemporary Native issues and how Native people are represented in the mainstream. In one of the episodes in which Dr. Kim Tallbear, who holds a Ph.D in the History of Consciousness from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and is the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Peoples, Technoscience & Environment, speaks, she said “We can be in good relation, or we can be in bad relation, but we are all in relation. Period.”

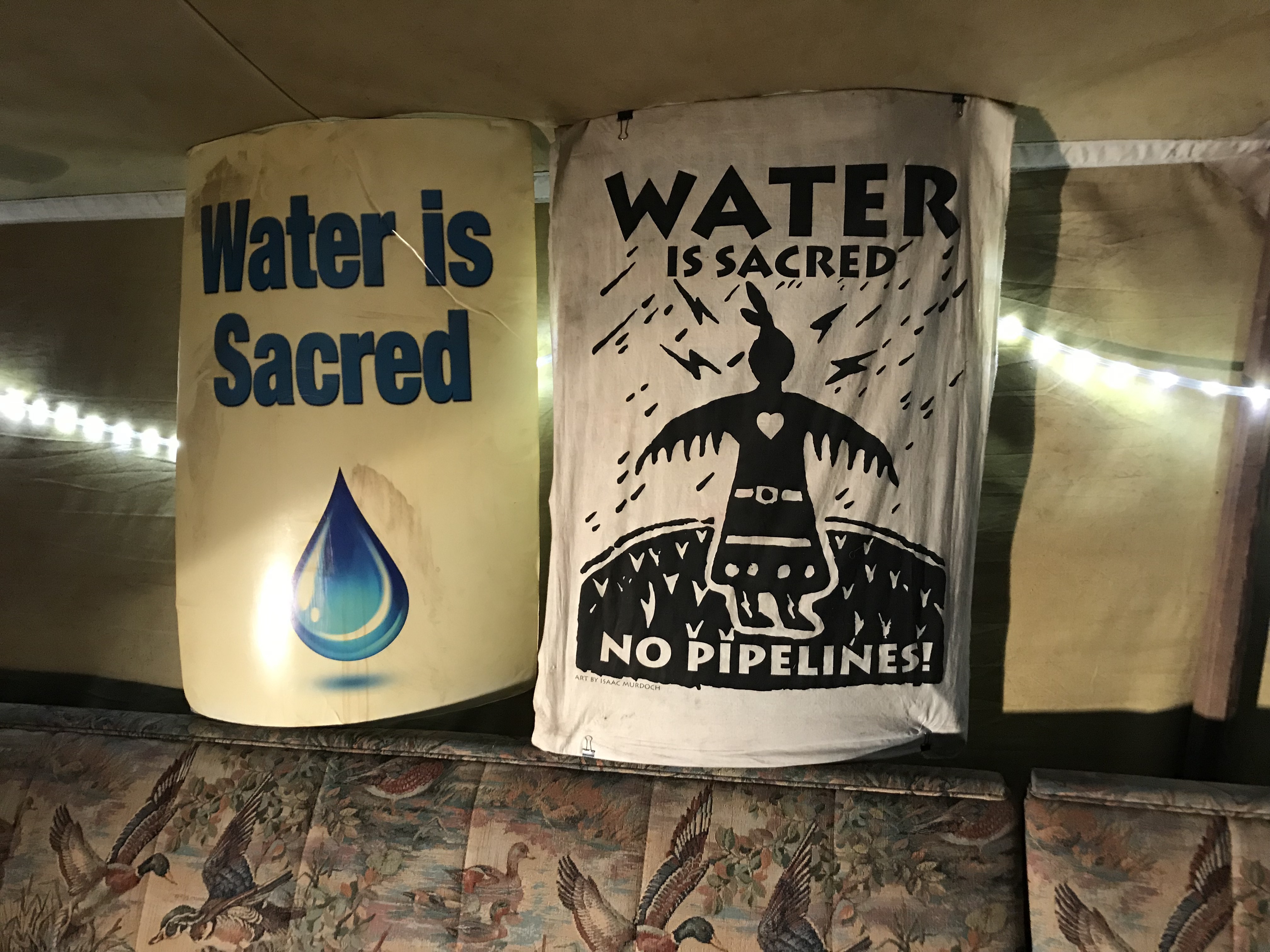

Water is sacred signs at Anishinaabek Camp. Photo: Frankie Pedersen, 14 East.

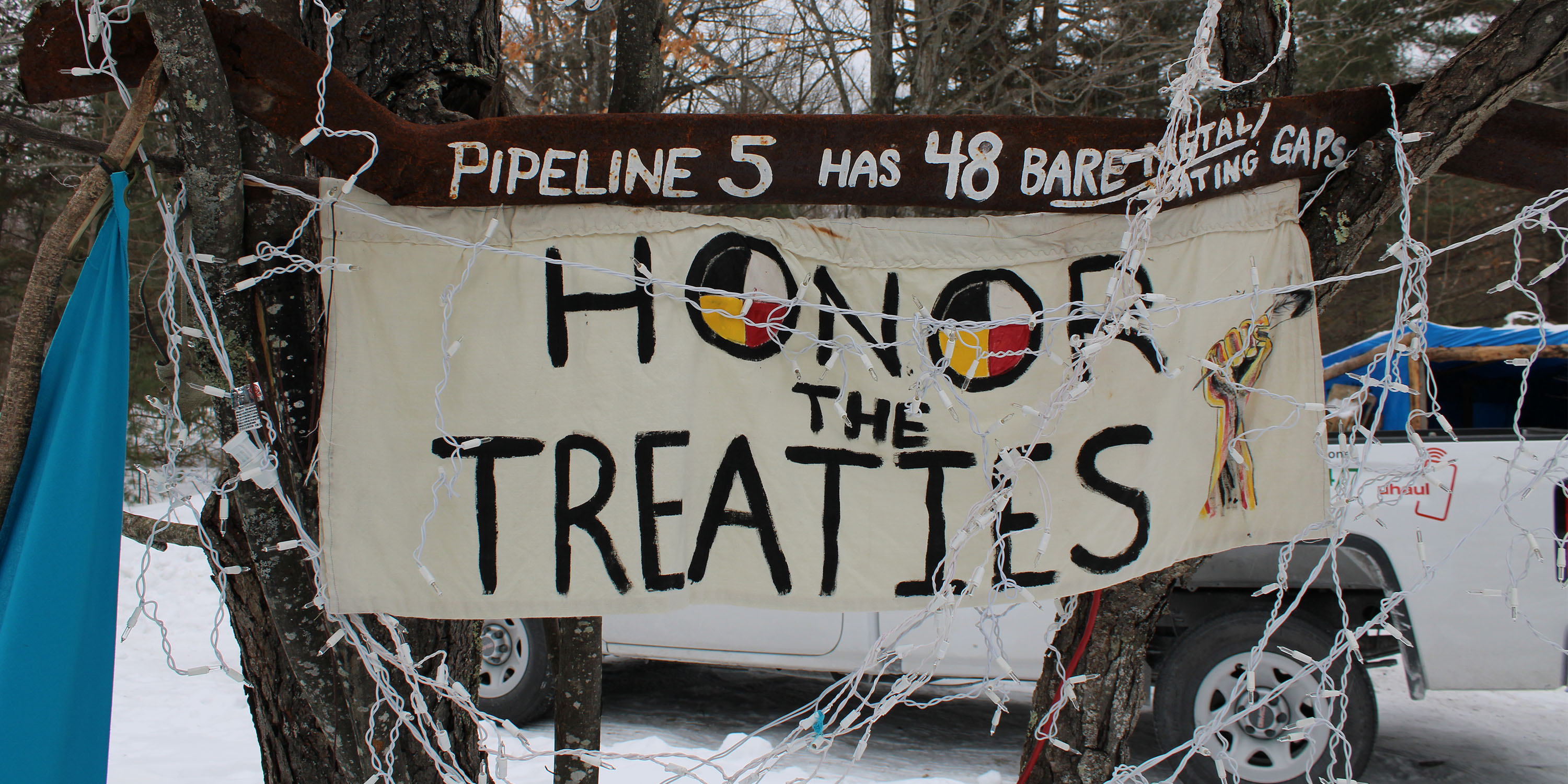

I have been working on a project that includes interviewing water protectors from around the country that have worked or are still working to defend water and land. I interviewed a few water protectors at the Anishinaabek Camp, a camp working protect the water of Lake Michigan and to shutdown Embridge Line 5, which is an oil pipeline that goes under the Straits of Mackinac. I spoke to Sarah Jo Shomin, a resident at the camp, who also demonstrated at Standing Rock three years ago. The way she talks about the Great Lakes is informative of how indigenous people see the world and our many relations.

“In Michigan, you grow up and they’re your friends, they’re your family, they live with us.” Said Shomin, discussing the Great Lakes, “We live together. So when I found out they were in danger, it was heartbreaking.”

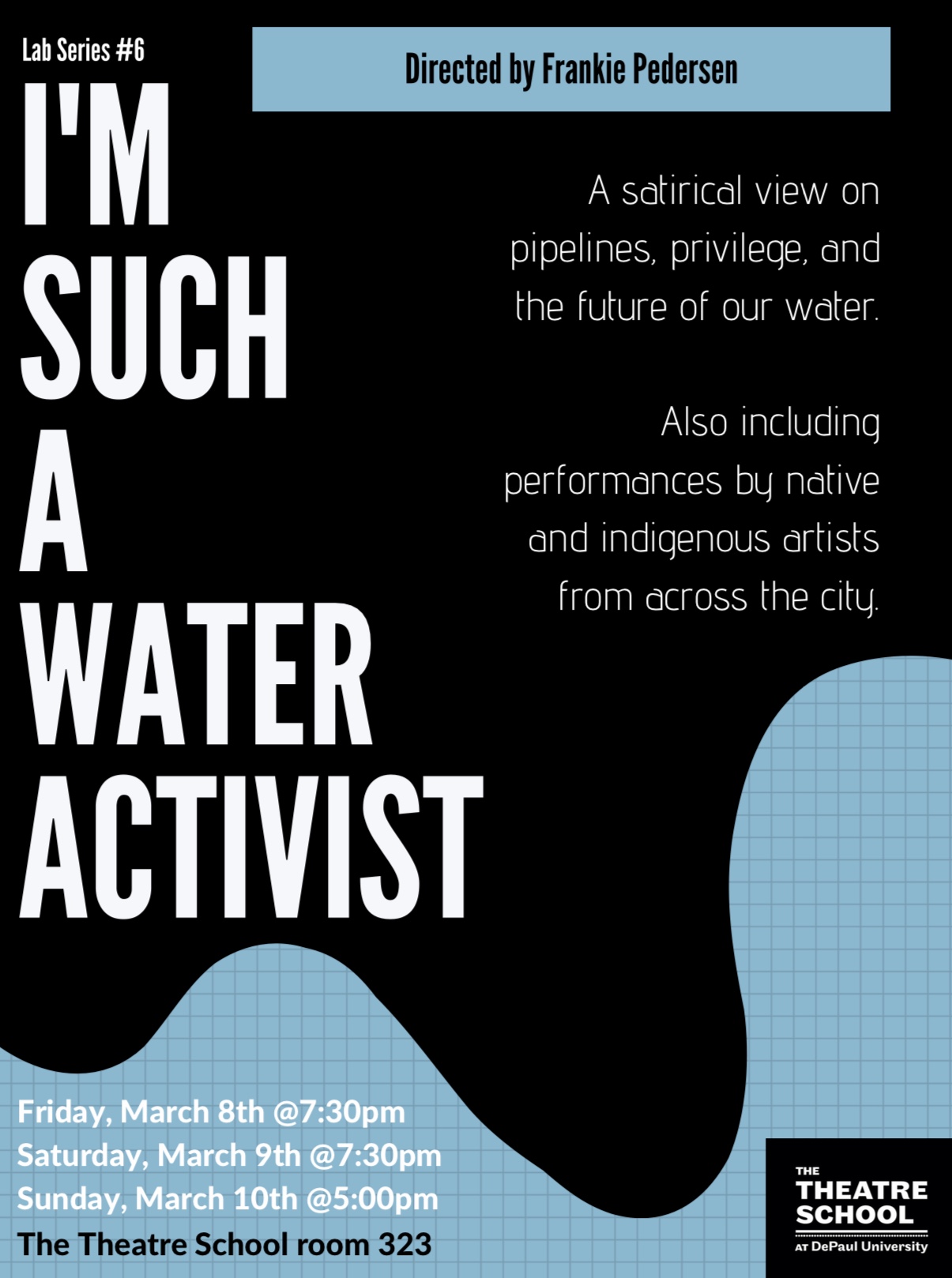

This project, which I will continue to pursue, was the starting point for my senior year lab piece at The Theatre School at DePaul University. My original idea for the project was to create monologues and scenes based off interviews to make this docudrama piece. But as life happens, and people’s schedules shifted, I found myself having to reframe how I was going to look at my topic.

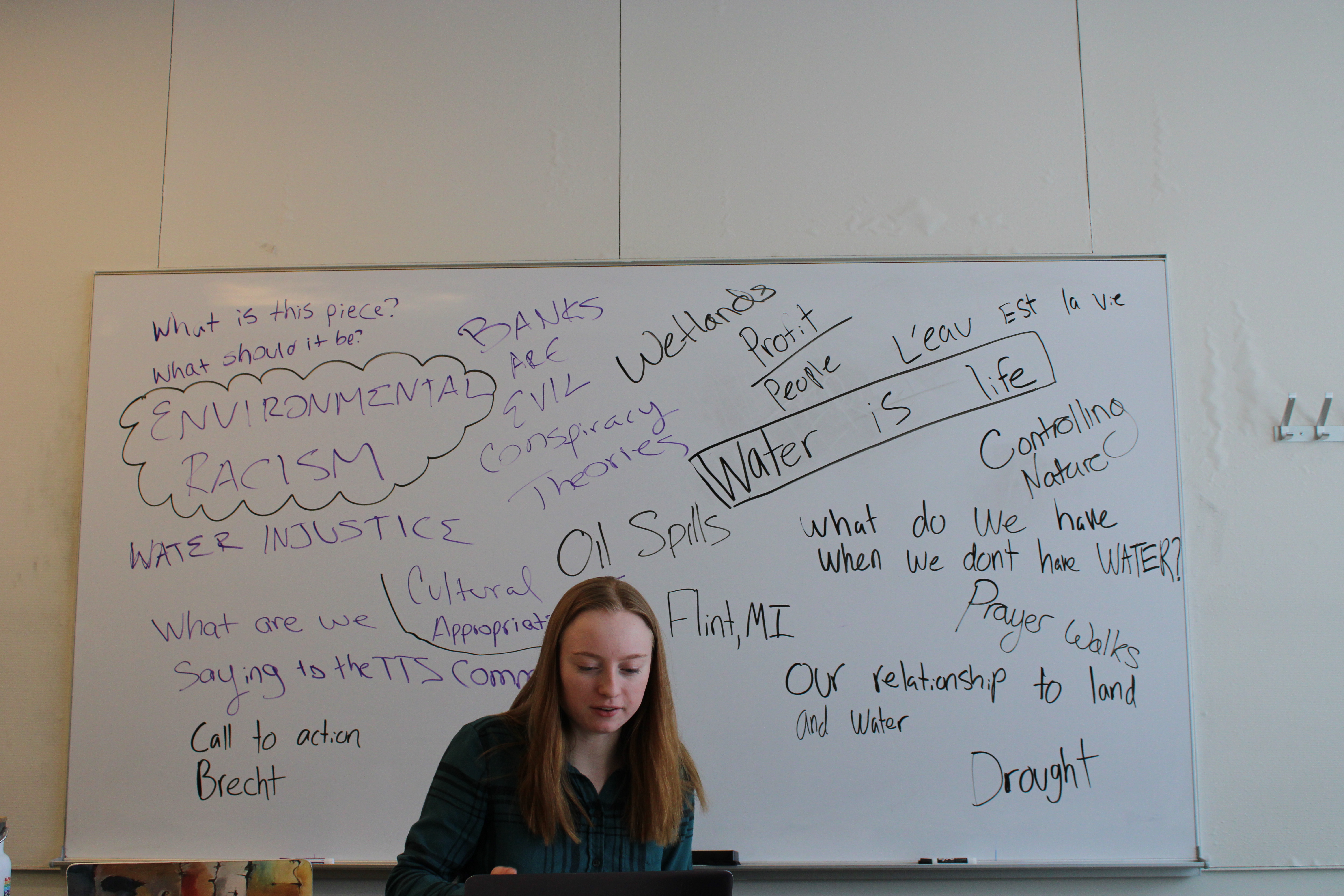

As I developed this piece, which turned into a satirical piece that looked at privilege, environmental racism, and the fight against big oil, I realized how many people, specifically non-indigenous people, think that everything ended after Standing Rock. When I was giving my first dramaturgical presentation at the beginning of the rehearsal process, many of my performers who I consider very strong allies, were still given a lot of information that they were not aware of. Instead of presenting information I thought they already knew, a lot of it was new information for them.

Contrary to popular belief, the fight against big oil did not stop at Standing Rock. In fact, one could argue that Standing Rock was the catalyst. This moment in history was a jumpstart for a whole movement, for which people continue to fight today.

There are still a handful of indigenous camps across the country that are defending water, land, and treaty rights. The Anishinaabek Camp in Levering, Michigan is trying to shut down Line 5, and L’eau Est La Vie is defending the Louisiana wetlands and trying to shut down the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, to name a few. All these camps emerged after Standing Rock, as well as a youth organization, International Indigenous Youth Council, that has chapters all across the country to inspire indigenous youth to be leaders in their communities and protect the environment.

We weren’t able to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016, and the pipeline has already experienced plenty of spills, including five spills in the first six months of use, but other camps and the use of direct action have proven to work. The L’eau Est La Vie Camp has been in operation since after Standing Rock, and has been defending the Louisiana wetlands against the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, which is the tail end of the Dakota Access Pipeline. It was announced a little more than a month ago that production on that pipeline would stop, because the water protectors have delayed construction of the pipeline for so long that the company was losing too much money on the project to continue.

This is one of the few wins we hear about coming from these camps. Big oil corporations clearly don’t care about the future of our land and water, and they definitely don’t care about treaty rights or indigenous people.

- Photo: Frankie Pedersen, 14 East.

- Photo: Cody Corrall, 14 East.

- Photo: Frankie Pedersen, 14 East.

Over the past fews days I’ve been seeing a lot of pictures and posts about the Notre Dame Cathedral catching on fire. How over the course of 24 hours, billionaires have pledged over 600 million dollars to help restore it. One of the largest and wealthiest institutions in the world, the Catholic Church, is accepting millions of dollars to restore the building.

I’ve seen a lot of posts about how many non-natives were feeling a sense of distress and hopelessness while watching the Notre Dame burn. While seeing any religious place of worship being destroyed is upsetting to me, as I scrolled through native Twitter and Instagram, many people have made the point that this feeling of pain is how native people have been feeling for hundreds of years.

The amount of sacred sites that have had pipelines ripped through them or have been leveled to build malls is alarming. This feeling of hopelessness and distress people felt watching Notre Dame burn is the same feeling many indigenous people feel when pipelines are being cut into the earth and our water is threatened. These large organizations have been destroying and building over our sacred sites and relatives. Native people have been defending what is sacred, and putting their life on the line to protect land and water, and have activity had to watch it be taken and destroyed.

The Notre Dame caught fire, and within a day we knew that there would be enough money and resources to immediately start fixing it. The cathedral is a place for worship that is full of history. But that’s much different than our sacred lands, right?

As many people sit by and watch sacred lands get torn through, our water poisoned, and as our communities still struggle to gain access to clean drinking water, the action of the people has proven to stand strong. The help of people like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Deb Haaland advocating for indigenous people and pushing a Green New Deal in congress, and indigenous camps popping up across the country to protect the water are all happening without the help of millionaires, the Trump Administration or the mainstream media. While it constantly feels like we are working against the clock, and at times I have to battle this feeling of hopelessness and devastation, this ongoing fight has shown me there is so much strength. While most people will not meet these devastations with the same sense of urgency or compassion that they did a cathedral, the people who did act have shown that they are strong, and this fight will continue for as long as it takes. Until everyone realizes that we are all in relation.

Header photo by Frankie Pedersen, 14 East.

NO COMMENT