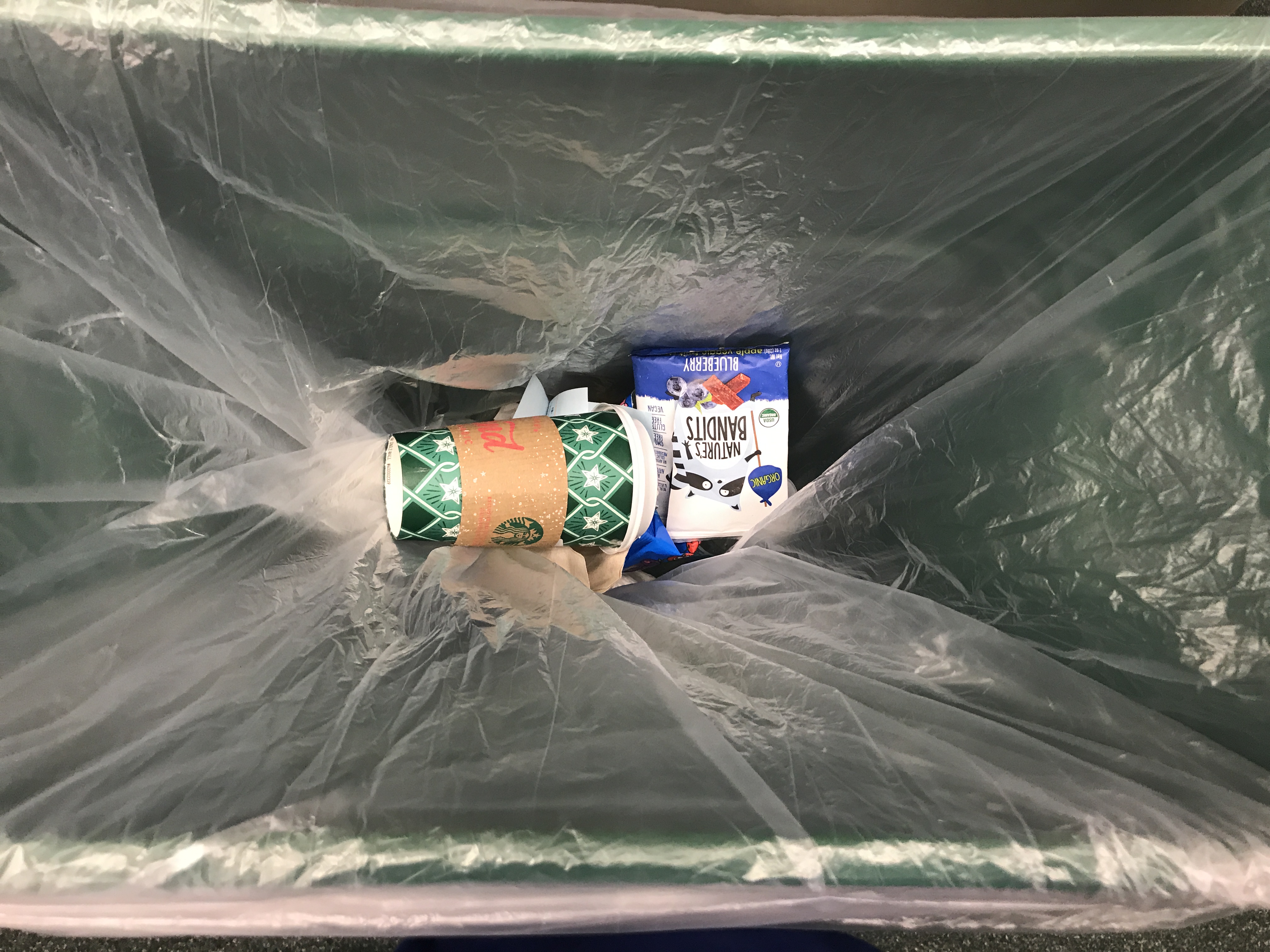

At first glance, DePaul’s recycling system looks messy. Some recycling containers look like portly mailboxes, others look like R2D2. They are blue, green, gray or taupe and reflective, cobblestone or wooden. Some outside containers operate through an elaborate drop slot, while others are dripping in sauce from the pizza box that rests atop them. What’s inside is unknown.

Similar to the diverse bins, DePaul has created different pathways and structures to increase sustainability on campus. As one aspect of sustainability, recycling weaves through campus and different departments. The loose ends of the recycling process are still not tied up as they exit DePaul, leaving people at both ends of the process still grasping at straws to understand it.

This article will explore the process, from the bins to recycled products, and sniff around for details. By understanding the foundations of recycling and its environmental and economic impacts, we can begin to sort through DePaul’s recycling system and efforts to improve our campus sustainability. But there are still unknown factors.

Photo: Meredith Melland 14 East.

How does recycling work?

“Recycling’s just kind of a messed up deal in general,” said DePaul student Twyla Neely-Streit, an environmental science major. “Most things that you think are recyclable just aren’t or are like kind of recyclable.”

Neely-Streit’s doubts stem from her confusion about the requirements of recycling and its environmental impact, which many people share. She didn’t plan to study environmental science when she started at DePaul in the fall of 2016, but ended up joining the program to help her deal with how “screwed up everything was” in the environment.

“There’s a guilt, an impending, constant guilt that is hard to get rid of, so this is like my one way of alleviating that guilt,” Neely-Streit said.

At its root, recycling is the process of taking used items or waste and remaking them into something different and new. This idea expanded into an industry in the 1970s in the U.S.

Since energy costs were rising, materials like used aluminum and paper were cheaper because they required less energy to produce. This process was popularized because of its profitability and environmental incentive — less trash gets deposited into landfills if paper, metal, plastic and glass materials can be put back into production.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began monitoring waste as soon as it was founded in 1970. States and cities over time developed legislation for the curbside collection of recyclable items.

The City of Chicago currently provides blue bin curbside recycling through the Streets and Sanitation department only to buildings with four units or less. Large businesses or multi-unit apartment complexes are left to find systems of recycling that work for them, whether that is through the contract of a licensed recycling operator or handling recycling off-site. In 2011, Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration contracted private recycling businesses Waste Management and Midwest Metal Management to encourage “managed competition” between services and save money. Lakeshore Recycling Systems is contracted now instead of Midwest Metal.

“Recycling tends to prolong the life of things, but it’s not like we’re refilling,” said Assistant Professor Christie Klimas of the Environmental Science and Studies department.

The recycling process is not the full circle its classic logo makes it out to be. Products are often not designed to be remade or serve the same process, and regulations conflict with that possibility. For instance, a plastic soda bottle that gets recycled will likely not be remade into a plastic soda bottle because the Food and Drug Administration requires that only fresh plastics be food-grade. Because the plastic bottle can get recycled into plastics for tables, but not into a bottle, it is down-cycled.

Another challenge recycling faces outside of downcycling is contamination.

“It’s hard because we want to recycle, so we look at things and say, ‘That should be recyclable,’ in spite of the fact that it’s not,” Klimas said.

Contamination — from food, liquids or other single-use waste — causes entire bins of recycling to be thrown out because the contents are too impure, or because problem items like plastic bags can clog machines. That’s why some recycling containers designate different shapes and colors for different types of items — keeping items like soda bottles separate from paper decreases the likelihood that the paper will get damaged.

Photo: Meredith Melland 14 East.

“If any amount of paper recycling gets wet, it goes into the landfill because it can’t be recycled,” said Sophia Modzelewski, Executive Vice President of Operations of the DePaul Student Government Association.

The third obstacle is that each recycling provider has different requirements for what materials they accept. City recycling policies are different from DePaul recycling policies, which can be hard to keep track of on the go.

“We see recycling as a solution, and it’s better than the alternative in many cases of throwing things away, but it could be masking the fact that we have a consumption problem,” Klimas said.

How effective is recycling at DePaul?

Recycling receptacles are easy to spot along the hallways and sidewalks around campus, but there is no publicly accessible data that indicates how much of the contents are successfully re-processed and how often they’re contaminated.

The Public Relations department’s “DePaul and the Environment” website states that DePaul has been recycling for 30 years, both collecting items in bins to ‘clean sort’ them and then send them to recycling centers for ‘in-plant’ recycling. This means that instead of collecting all recycling items in one single stream, they do some pre-sorting by using different receptacles for different things. “As a result of both efforts, DePaul recycles over 40% of its waste stream.”

Logistically, the department of Facility Operations handles recycling. The university has contracted different vendors over the years to handle recyclables. Facility Operations currently contracts Republic Services to collect DePaul’s trash, composting and recyclables.

Republic Services, incorporated in Delaware in 1996, claims it’s the nation’s second-largest trash and recycling company. As of December 2018, they operate 341 curbside waste collection services, 190 landfills and 91 recycling centers in municipalities in 41 states. They also accept business and institution contracts usually lasting for one to five years, but can be arranged for longer deals, according to the company’s annual 10-K report. Republic Services could not be reached for comment on its contract with DePaul.

Republic Services posted a net income of $1.04 billion in 2018 in the company’s 10-K, a drop from $1.28 billion in 2017. However, the company’s stock price has increased by $45 in the last five years and is currently at $79.04.

Republic Services operates trash and recycling dumpsters around campus, though the frequency and volume of the amount deposited in each dumpster varies by time. All of the recyclables get co-mingled in the truck and hauled to one of Chicago’s Republic recycling sorting centers: Shred-All in New City and Planet Recovery in the Near West Side.

After that, DePaul is out of the contract and is no longer obligated to see the process through.

“I kind of feel that DePaul tries to portray itself as being a pretty front-of-the line accepting and forward-thinking place, but I think people tend to go for social issues and tend to forget about environmental or more physical structural issues,” Neely-Streit said.

Is recycling the best way to be sustainable?

In October, Better Government Association reported that Chicago only recycles nine percent of its waste and that its system is mismanaged because Waste Management, one of the companies it contracts, also operates a landfill that they have an economic incentive to dump waste in.

This kind of activity can cause distrust, which may be why Neely-Streit feels so alienated by the system.

However, DePaul’s Student Government Association (SGA) is working to change that. Modzelewski works directly with Facility Operations and SGA Sustainability Senator Kaitlyn Pike to develop new recycling ideas that work for students and their schedules.

“I know I’m not perfect when it comes to sustainability, so I’m just trying to find systems that work and systems that are easy,” Modzelewski said.

Klimas commended previous SGA staff members for developing helpful recycling signage. The current SGA has cut down on the use of straws on the campus, but kept them available by request. They also have installed a system with Facilities to improve the effectiveness of recycling clusters by moving them out of classrooms and into hallways.

“Students can take a little bit more time to like take their soda bottles and put it into the right container and make sure their paper goes into the paper container,” Modzelewski said.

She hopes this will cut down on contamination because students won’t put items into the wrong containers as they hurry to leave class. Neely-Streit disagrees with this model.

“Adding more drop-off spots is always going to increase the amount of recycling of whatever you want to happen.” Having more of bins available will make people use them more because they don’t have to walk far, she said.

Both students and Klimas think that the efforts being made should be promoted more so that they don’t go unnoticed. For SGA, that means taking to social media.

“Our PR Coordinator helped us make a Facebook Live video showing what happens behind the scenes to food waste on campus and we posted it to our Facebook Live and have been promoting,” Modzelewski said.

SGA is the main avenue through which students can have a voice in DePaul’s recycling program. The university previously had a Sustainability Initiatives Task Force that started in 2009 to create the Institutional Sustainability Plan, where they determined that DePaul should work in four different areas: curriculum, operations, research, and engagement. Later, it was disbanded.

“The idea was that the next step would be a sustainability coordinator who would move some of those ideas forward because it had been done by a really committed group of faculty and staff, but none of whom could work full time on some of these initiatives,” Klimas said.

When the university didn’t hire a sustainability coordinator, some were disheartened.

“People had been spending an awful lot of time and they felt like they were not being supported in these efforts, and I think that plenty of those people just allocated time to other things,” Klimas said.

“The group then became the DePaul Sustainability Network (DSN) to pursue various elements of the ISP. Because those efforts are spread across the entire university and there is no central office to continue reporting on those efforts, the DSN returned to a series of ad hoc initiatives,” Scott Kelley, associate vice president for mission integration in the Office of Mission and Ministry, wrote in an email.

Kelley did not respond to questions relating to the current activities or members of DePaul’s Sustainability Network. The “DePaul and the Environment” site still links to a “Sustainability at DePaul” page, which defaults back to the Division of Mission and Ministry’s page.

Photo: Meredith Melland 14 East.

How do we move forward?

Making proper disposals in the campuses’ recycling set-up is a good habit to get into, Klimas said, but even more important is limiting consumption of single-use or throw-away materials. If we reuse instead of recycle, it’s easier to be more connected with the downstream effects of your waste.

“Say if you had a waste product and somebody else could use that, you could sell it to them before it ever entered the waste stream so it wouldn’t be a waste, it would be sort of a revenue-generating source for you,” Klimas said.

Modzelewski and Neely-Streit agree, but recognize there are still convenience and information barriers preventing significant change.

“If we could get rid of styrofoam on campus and get rid of single-use products and have everyone carry mason jars and bamboo utensils, that would be fantastic, but that’s also not feasible,” Modzelewski said.

Constraining waste inside an array of bins can promote an “out of sight, out of mind” mentality. By examining surroundings, using resources and taking cues from student and environmental leaders, campus consumers can think about the items they hold in their hands and aim their tosses intentionally.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this piece listed Republic Services’ net income in trillions, instead of billions.

Header image by Meredith Melland

NO COMMENT