It was 1961, at the height of the Cold War, when the United States and Cuba severed their diplomatic relations, thus beginning a tumultuous relationship that lasted for 54 years.

Over the years, Cuba, the only communist nation in the Western Hemisphere, was the subject of numerous human rights violations under the Castro family. The United States placed an embargo on Cuban goods. The embargo remains intact to this day, aside from Cuban cigars and a few other specifically selected Cuban-made products. A newly-elected President Donald Trump supported the embargo despite the relaxed travel restrictions the Obama administration both favored and negotiated.

Today, Cuba is still shrouded in a dark veil of secrecy. According to a report from Reporters Without Borders, Cuba is ranked 169th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index, up three spots from last year. Still, since the first index was released in 2013, Cuba has yet to emerge from the lowest tier, or black, grouping. The methodology behind a country’s score relies heavily on several criteria. Those criteria include pluralism, media independence, environment and censorship, legislative framework, infrastructure, abuses and of course, transparency.

The underlying assumption is that stories rarely see the light of day in Cuba. Fear and intimidation plague reporters and sources alike. But here in America, we work hard to make freedom of speech the most essential aspect of our modern democracy. And yet, some people wait years to tell their stories, for the wounds they reopen are sometimes too painful to heal a second time. We must lift them anyway, for the insights they provide may give us a new perspective into the past we so desperately need to understand.

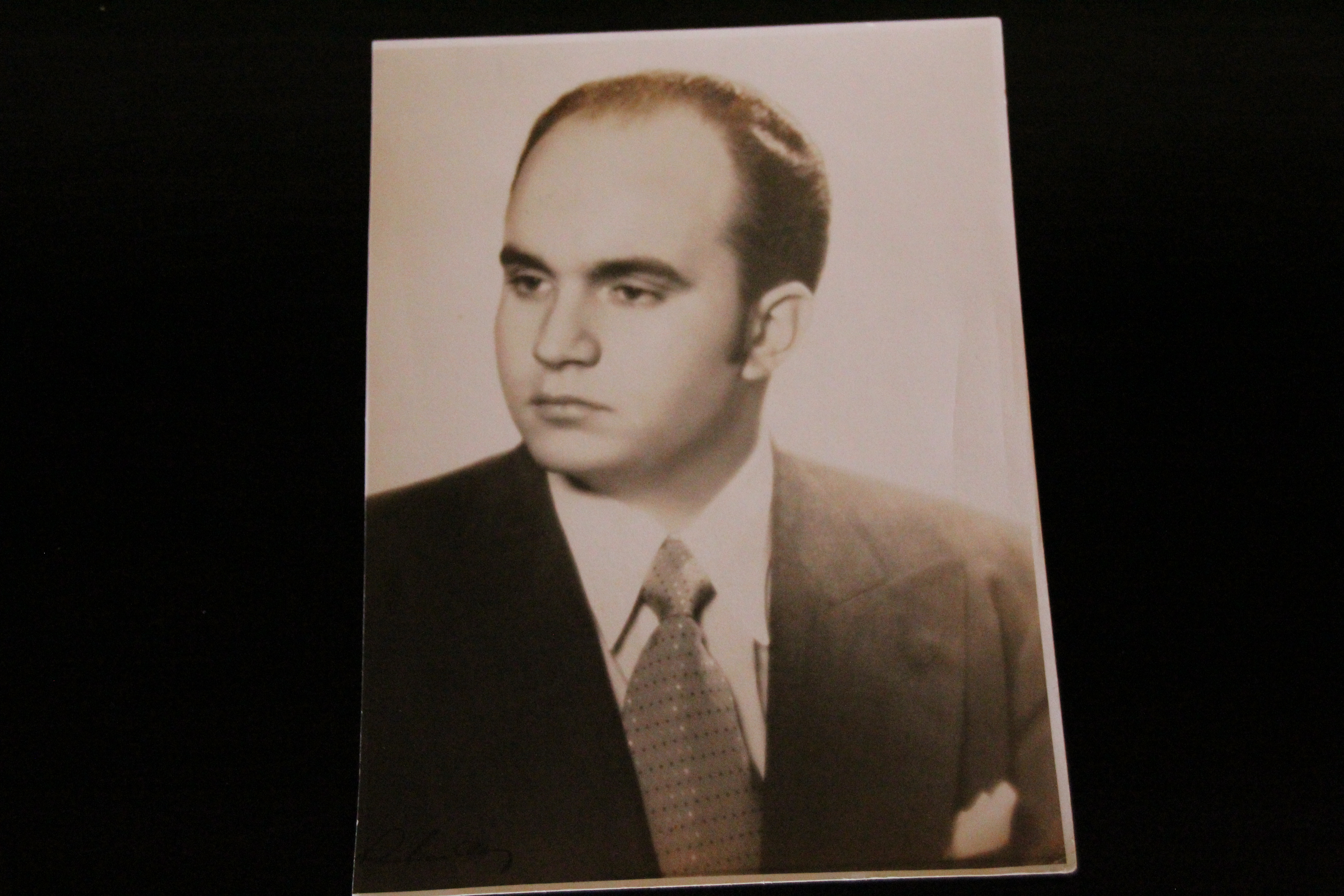

As we turn back time in Pedro Portela’s mind, he is sharp and lucid, allowing his conscious to speak for him as we opened the door this 88-year-old man has kept only slightly cracked for many years.

Inside is the story of Cuba, the home he once knew.

Photo by Rich Bodee, 14 East.

It was a humid day with temperatures in the upper 80s when I arrived in Houston’s Galleria neighborhood to visit Dr. Pedro Portela, a Cuban lawyer and immigrant with a unique view of Cuba’s path during the revolution.

We had spoken by phone several times in the weeks leading up to our face-to-face interview. Pedro had me enthralled with stories of the Cuba he once knew and his relationships with a colorful cast of characters. People like actors, mobsters and former politicians — one of which being Fidel Castro himself. That was the initial hook that reeled me into visiting him.

I entered the lobby of his and his wife, Gloria’s, high rise condominium building and was welcomed into a luxurious setting. Pedro’s daughter, Maria Elena, met me in the lobby to take me up to her parents’ apartment. I knew Maria well. She and my uncle had been dating for the better part of the last 14 years. Suffice it to say, Maria is family. She was the one who had initially told me little pieces of her father’s story months earlier, which sparked my interest.

We arrived at the 12th floor and walked to their apartment. After a quick introduction, we walked down to the 7th floor to a beautiful vista with a pool and a jacuzzi overlooking The Galleria. I followed Pedro into an indoor conference room that he had reserved for our meeting. As we sat down, Pedro said, “So…what do you want know?” And so we began.

Pedro, the eldest of four children, was born in Havana, Cuba, on January 11, 1929, to Alfredo and Maria Teresa Portela. He had one brother and two sisters. His youngest sister, who is a decade younger, is his oldest surviving sibling.

Both of Pedro’s parents were highly educated. Pedro’s mother, Maria Teresa, had a doctorate in teaching. Pedro’s father, Alfredo, who was affectionately known as “el viejo Portela,” (old man Portela) was a well-respected lawyer. He graduated law school at age 18 and became a partner at one by 25. He went to work for a former Mayor of Havana and Secretary of Justice, Estanislaw Cartaña. Cartaña later became the confirmation sponsor to Pedro’s younger brother, Alfredo Jr., who was affectionately nicknamed “Alfello.”

Pedro’s father, Alfredo, never wanted to get into politics despite initially working for a law firm comprised mostly of former Supreme Court members. That didn’t stop influential politicians from seeking him out. In fact, in the 1940s, Cuban Vice President Cuervo Rubio offered Alfredo the job of Justice of the Supreme Court.

“My father refused though,” Pedro said. “He said, ‘The Justice of the Supreme Court must behave like the wife of Caesar.’ You know, appear to be clean and good. My father liked to gamble.”

Pedro was raised in Havana until age 14 when his family moved to Palmas Gemelas (Twin Palms), which was located in the province of Havana. Interestingly, the location was noteworthy in that the property neighbored the estate of Fulgencio Batista, the former dictator of Cuba before the Castro revolution. Palmas Gemelas and Batista were only separated by a central highway and a small railroad track.

Pedro described his upbringing as normal, although his mother tragically passed away of multiple sclerosis at the age of 42.

Pedro attended Belén, a Jesuit school in Havana. “I went to Belén from the beginning all the way up to college,” Pedro said. Belén was where Pedro first met Fidel Castro, who was one year ahead of him at the time.

It should be said that Pedro was very careful not to call Castro a friend, but rather, “a classmate.” However, over time, their relationship became more and more nebulous.

For recreation, Pedro enjoyed playing baseball and tennis. “Growing up, I probably played baseball with Fidel before and didn’t even know it was him at the time, but I can recall him at Belén,” Pedro said. “He was a pretty good athlete. He liked to play baseball, throw the javelin, and I believe, he ran the 800m race.”

Castro graduated from Belén and went to University of Havana for law school. Pedro recalled a time when Fidel came back to Belén for a visit while Pedro was completing his final year.

“Fidel was back visiting the school and his old teachers when he saw me and walked over,” Pedro said. “Fidel said to me, ‘Listen Pedro, I am starting a “group of action.” I’m looking for thinkers, not fighters and I would like you to be part of it.’ I said to Fidel, ‘Let’s wait and see. I’m not even in law school yet.’ Fidel was content with that answer.”

Pedro never heard Castro openly support communism, at least not until many years later, and when Castro finally did, he announced it to the world.

Pedro graduated from Belén in 1946 and decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a lawyer. He went to the University of Havana.

Photo by Rich Bodee, 14 East.

The university had a process of delegating authority, which Pedro described in great detail. “The University of Havana had thirteen different faculties; law, medicine, etc. Each of the thirteen faculties had five delegates,” Pedro said.

He was one of five delegates in the law program. Collectively, the delegates elected one president. So, there were thirteen presidents who represented each faculty. Those thirteen presidents then elected one president. The entire process was a springboard for national politics.

“My first year as a delegate, we elected Baudilio Castellanos as the president of the law program,” Pedro stated. “At the time, we didn’t know he was a communist, just that he was a big buddy of Fidel’s. Castellanos helped Fidel get elected the second year, but Castro lost some time because he was involved in politics. He actually graduated law school after me.”

Pedro recounted two other memories involving Fidel from school, harkening back to their law school days. The first memory occurred when Fidel got into a fight with another student.

“I remember Fidel got into a fight with Ramon Mestre, a fellow classmate,” Pedro said. “It was a pretty good fight, but Mestre won. I saw Mestre years later in Miami and he wanted to get together for lunch at La Rosa.”

The other memory occurred when Castro came to Palmas Gemelas, Pedro’s home.

“Fidel had been to my house on a few occasions,” Pedro said. “But he always had it in the back of his mind that Palmas Gemelas wasn’t producing.”

Palmas Gemelas was a recreational farm that produced small crops, including a variety of fruit, enjoyed primarily by the Portelas. However, Castro always looked at it from the perspective that the Portelas hadn’t maximized their economic usage of the property, as he thought it should be an income producing venture.

“I would tell him to cut it out because he’d been there before and he knew we used it for ourselves only,” Pedro said as shook his fist angrily. It was almost as if the memory came alive and he could visualize talking to the ghost of Castro about the lack of production on his family farm at a dinner party so many years ago.

Another memory Pedro recalled was the shooting of Justo Fuentes. “I vaguely remember the shooting, I just remember it being a big deal,” Pedro said. “Justo Fuentes was a tall, black guy in the social science department at University of Havana and he was also involved in politics.”

It is commonly known that Castro protested the killing of Fuentes. The impact of Fuentes’s murder on Castro’s psyche is unknown. However, one can only wonder if this tragic event was a catalyst behind the ignition of Castro’s communistic ideals, given the widespread corruption under Batista.

“Some people say he turned communist because of this or that,” Pedro began. “Others say he was born that way. I guess we’ll never know.”

After graduating from law school in 1951, Pedro joined his father’s law practice. Pedro’s younger brother, Alfello, also joined the law firm after graduating from law school several years later.

While Pedro was working for his father, he had several runs-ins with some important people. One of which was Che Guevara.

“This happened sometime in the late ‘50s,” Pedro said. Guevara wasn’t appointed as President of the National Bank until 1959.

“I had a couple of Cuban clients that owed money,” Pedro said. “They were creditors and in order to pay the American companies, they needed to convert their pesos to dollars. My father’s friend had a son who was Che’s assistant, so I could gain entry into the National Bank and supervise the transaction.”

Pedro remembered walking through the bank to a back room.

“Two of Che’s bodyguards were being taught to read and write in Spanish by a blonde woman in the corner,” Pedro said. “Then Che walked in. I wasn’t interested in shaking his hand, I never liked him very much…and neither did my dad. You know he supposedly had a medical degree?” Pedro said, as he rolled his eyes.

As the head of the National Bank, Guevara was responsible for signing all the pesos before the exchange of money could occur.

“I think that one of the greatest insults to the people of Cuba was that Che signed all of the bills using his popular nickname and signature, ‘Che,’” Pedro said. “He couldn’t just sign his full name like you’d expect.”

“On a separate occasion, I remember seeing a reporter trying to ask Che a question by calling out his name,” Pedro began. “Che turned and walked up to the guy and said, ‘To you, I am Dr. Guevara.’”

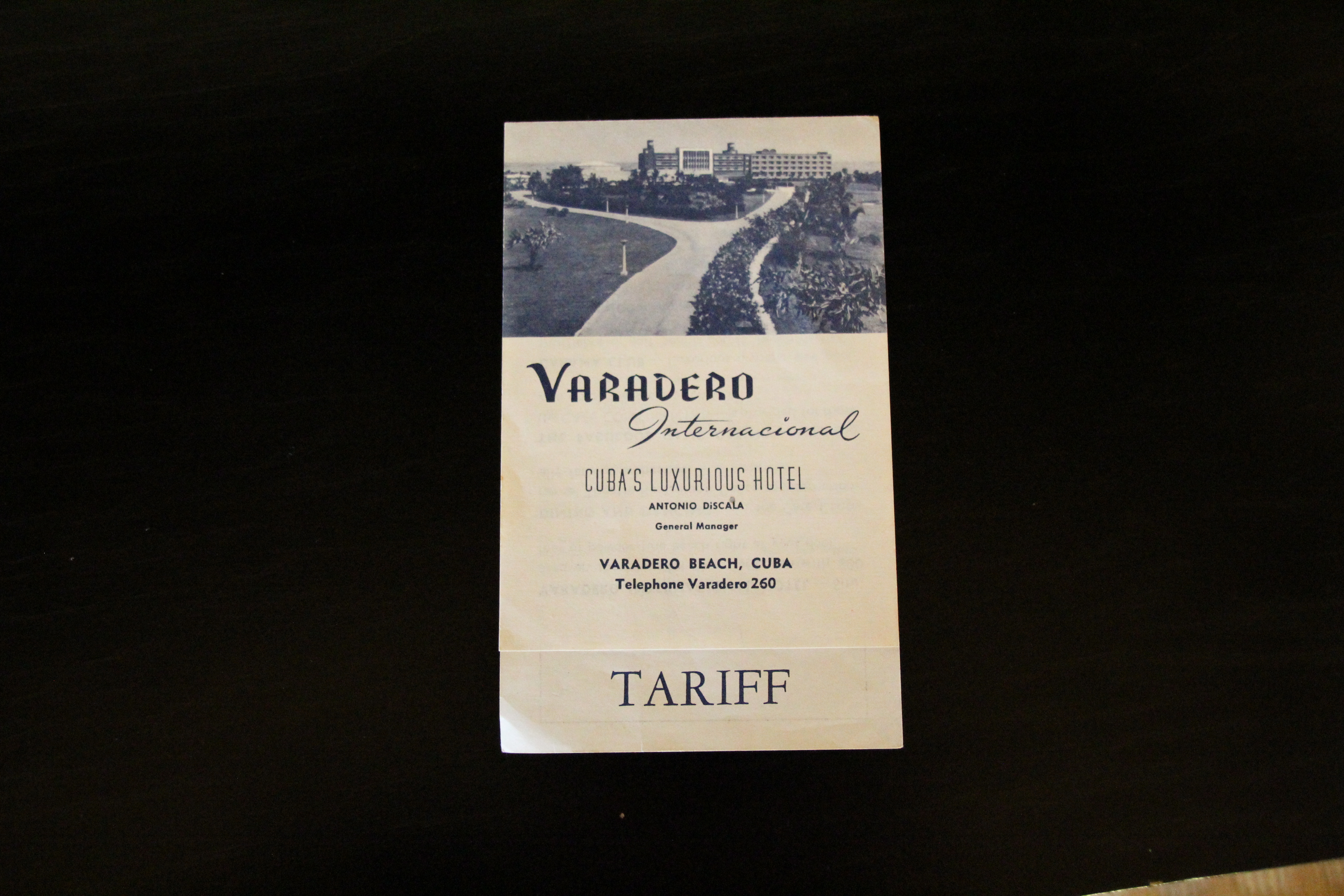

Pedro’s other run-ins happened with several notables occurred as a result of his position at Hotel Varadero Internacional. To fully appreciate the significance of these events, you need to understand the backstory of the hotel.

“I’m going to put Varadero on the map of the world,” Pedro recalls William Liebow, the owner of the hotel saying. “Liebow also owned the Robert Clay Hotel in Miami and a hotel in Panama as well, but he fell in love with Varadero Beach, which is located less than a two-hour drive from Havana. Liebow hired the company of Mira and Rosich to build the hotel. My father did all the legal work. That’s how we first got involved.”

“Between my father, myself, and Rosich, we would take turns visiting the hotel,” Pedro said. “It was the best beach I have ever seen. You could walk 100 yards out into the water and it would still be crystal clear and at your waistline. The hotel had a 900-ft. ocean-front view, plus I always had a bottle of Chivas Regal waiting for me when I arrived. That was the life!”

Gloria chimed in, saying: “Varadero is unforgettable. The water was like bath water. It was called ‘la playa azul.’”

“The penthouse was normally off limits,” Pedro said. “The only person who ever stayed there was William Astor who owned the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City. In fact, I stayed in the Waldorf on my honeymoon.”

“The only bad thing about working for the hotel were the labor disputes,” Pedro said. “The unions would constantly call on me.”

“One time, I was in a dispute with local union leaders about the labor contracts when Rolando Cubela Secades, the Commander of Castro’s Revolutionary Army, walked in,” Pedro said. “I always called him ‘Torpedo’ and he called me ‘Calvo,’ (bald one). I tossed him a key to one of the suites and he went up to the room. I guess sometime later, some of the union leaders went to Cubela’s room and wanted Cubela to convince me to go along with their plan, since Cubela knew me. Apparently, Cubela said, ‘We did not have this revolution for you to complain. It is time for everyone to cooperate.’”

Cubela was a close friend of Pedro’s brother, Alfello. “I remember Alfello telling me that Cubela came to him one day and said, ‘Alfello, you need to leave,’” Pedro said, as they were concerned about the shake-up in the government and Cubela’s role.

“Cubela wanted to defect to the United States,” Pedro said. “At some point, he spoke to the FBI and said the only person he trusted was Alfello.”

That night, Alfello went to the airport to get on a plane to Miami, but he was turned away. Cubela saw Alfello the next day and Cubela physically took him back to the airport and made sure he got on the plane.

“The next time I saw my brother, it was a year or so later in Miami,” Pedro said. “Cubela, of course, stayed in Cuba. Years later, Cubela was arrested for conspiring to kill Castro. I was worried about my father because Cubela visited our house fairly often.”

According to Pedro, other visitors to the hotel included mobsters, as the mob had a foothold in Cuba.

“Mobsters would come to my office asking to buy the hotel,” Pedro said. “I would tell them that the owner was gone and I could not tell them anything. It’s hard to intimidate someone when you aren’t in your own country. Although, the mobsters did go to the American ambassador to try and leverage him because Rosich was an American citizen, but Rosich told me nothing ever happened.”

But that wasn’t Pedro’s only run in with mobsters.

Photo by Rich Bodee, 14 East.

“Meyer Lansky owned the Riviera and I was there for a meeting with Leonard Hicks of Hicks and Associates, a Chicago-based company,” Pedro said. “I was meeting Hicks for advertising plans for the next season when Meyer Lansky walked in. We shook hands and exchanged pleasantries in passing. After our meeting, I pulled out my wallet to pay for the food and drinks we ordered, but the bartender said, ‘Mr. Lansky has already paid for the check.’”

Pedro also recalls seeing Louis Santos Trafficante, a prominent mobster embedded deep in the seedy gambling industry that Cuba boasted in the 1950s, and George Raft, an actor and dancer with connections to organized crime, outside of the Capri Hotel Casino. “Raft frequently stood outside as a greeter,” Pedro said.

Pedro vividly recalled all of these encounters, but one stood out more than most: the time Castro came to the hotel with renowned philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

“I believe they (Sartre and Beauvoir) were vacationing in Cuba, but I don’t remember where they were staying,” Pedro said. “I was eating when an employee came over to me very excited. He told me Fidel was outside standing in the sand with a couple of people. I got up right away and walked out to the sand to see where they were.”

Pedro said he had only read a little of Sartre’s work, so he was somewhat familiar with him, but he hadn’t read any of Beauvoir’s work.

“Fidel introduced me to them,” Pedro said. “As we exchanged pleasantries, I was confused because Fidel didn’t speak French. So, I said, ‘Fidel, how can you understand these people?’ Fidel thought for a moment, his mind was always working, then he said, ‘Yeah, but I remember your French was pretty good.’”

In fact, Pedro spoke four languages: English, Spanish, French, and a little Italian, which no doubt came in handy when he met critically acclaimed Italian movie producer Dino De Laurentiis and his wife and Italian film star, Silvana Mangana, at Arechebala, a business owned by the heirs of the Arechebala fortune. Pedro even tells a story of when he met high-end French fashion designer Christian Dior. Dior so admired Pedro’s tie that he sent Pedro two ties of his own design.

As Sartre, Beauvoir, Pedro, Castro and his bodyguards stood in the sand, Pedro had an idea.

He said, “Fidel, why don’t we show them the view from atop of the hotel?” Fidel loved the idea, as he had never been to the top of the hotel before either. “Fidel put his arm around me and people from the hotel were watching. Their mouths dropped wide open and no one could accuse me of being counter-revolution.”

Sartre and Beauvoir were both highly intelligent and celebrated philosophers with unusual tendencies. Sartre was a known supporter of Marxism who widely praised Che Guevara. I was curious if either Sartre or Beauvoir had said anything specifically atop the hotel while looking out over the breathtaking view.

“‘Oh, what a beautiful view…’ that type of bulls—t,” Pedro responded.

As the four of them descended from the hotel’s rooftop and walked to Castro’s car, Fidel stopped Pedro.

“Fidel asked me how my old man was doing and I said he was doing so-so,” Pedro said. “Fidel said, ‘Well, make sure to give him a big hug for me!’ It wasn’t until later that that son of a bitch took my hotel from me.”

In fact, when William Liebow died, the hotel’s Board of Directors, which included Pedro’s father Alfredo, met to appoint a new president. Alfredo cleared up the controversy quickly and appointed Pedro as the new president.

Before the nationalization, Pedro remembers things beginning to change.

“There was a captain in Castro’s army who was concerned about the possibility of communism spreading and he said things like, ‘Castro is going to give in to the communists,’” Pedro recalls. “Six months later, the captain was executed.”

The foundations of a dictatorship were forming and Pedro came face-to-face with it one evening.

“One night, it was after 10 p.m. when I heard a noise outside,” Pedro said. “I yelled to see who was there. It was three or four guys with the rebel army and they wanted to search my property for guns.”

At the time, Pedro’s four young daughters were sleeping in their bedrooms upstairs and Pedro didn’t want the rebel army to “scare the s—t out of them,” which is what he told them.

“I told them I had no guns and I persuaded them not to check my house,” Pedro said. “I also told them that my father wasn’t home at the time, but he had a .22 rifle at his house across the property and if they really wanted to, we could all go over and check it out, which they did. I walked them across the property, they searched my father’s house, inspected his rifle, and then they left.”

Even after these two incidents occurred, Pedro wasn’t sufficiently alarmed by the shifting dynamics within Cuba’s government to believe he would need to flee his homeland, although the seeds were planted in the back of his mind.

“We used to say that the revolution was like a watermelon, green on the outside and red on the inside,” Pedro said.

But thought differs from reality and Pedro would soon be confronted by the full impact of Castro’s brewing revolution. There were three incidents that pushed Pedro over the edge. The first incident had to do with the nationalization of Pedro’s hotel.

“The idea behind the nationalization was for Castro and the government to take over all of the businesses in Cuba for six months to solve labor disputes,” Pedro said. “But they never gave them back.”

“Shortly after Castro took power, I received a phone call from the resident manager of the hotel in Varadero,” Pedro said. “He told me that ‘the intervenor’ (Castro’s appointee to oversee the nationalization) was at the hotel and said the hotel was being taken over. I arrived at the hotel two hours later. I was met by a man wearing a suit, ‘the intervenor,’ who gave me a copy of the intervention document.”

“The next day, we had a meeting with the Labor Department in Havana,” Pedro said. “They told me they would return the hotel to me, but with restrictions. Any action needed to be approved by the unions. I was furious because I thought I was going to be given back my hotel. I told them, ‘I didn’t come here to accept your demands. If you aren’t willing to give me my hotel, then my presence is no longer necessary here.’ The following day, I explained everything to my employees and I received a standing ovation. I was told Fidel would be at a Young Pioneers Club (the name for the group of people that supported the revolution) meeting the next day and I should try and talk to him then.”

“Fidel was supposed to be closing the meeting,” Pedro said. “But he never showed up. I ran into Cubela there though. I said since he was a friend of the family and close with Castro (at the time), maybe he could talk to Fidel about the hotel.” Pedro was optimistic, but that was short-lived.

“On the radio the next morning, it was announced that Fidel had officially nationalized three businesses overnight, one of which was the Hotel Varadero Internacional,” Pedro said. “What can you say? There was nothing to be done.”

Shortly after Fidel nationalized the hotel, he called to speak with the intervenor. The call was answered by the hotel’s operator, who heard a voice on the other line say, “Hello, this is Fidel Castro, I’d like to speak to the intervenor.” The operator didn’t believe it was really Castro and passed the phone to the concierge, who also didn’t believe it was him.

“The concierge kept saying, ‘Don’t bulls—t me. Who is this?’” Pedro said. “Fidel said, ‘This is really Fidel Castro. Tell the intervenor the intervention is done and we all just have to get along now.’”

Pedro kept trying to get in touch with Castro and speak to him directly, but his attempts were futile.

The second incident involved a teacher who was an American citizen.

“I knew a teacher, with the last name Coleman, from one of the nearby schools,” Pedro said. “One day, I saw him and his daughter at a café. He invited me to sit down and have a cup of coffee. Then he said, ‘Pedro, I need to get out of here.’”

At the time, the diplomats were running the American Embassy and the teacher couldn’t get his money out, even though he desperately wanted to.

Pedro said, “I asked him why he wanted to leave so badly and he turned to his daughter and said, ‘Tell my friend here how many fathers you have.’ The little girl turned to me and said, ‘I have two fathers, my dad, whom she pointed at, and Father Fidel.’”

Brainwashing and propaganda were taking over the schools. Pedro even described a method of brainwashing that included ice cream.

Government officials would approach students and ask them if they wanted ice cream, to which the students would always answer yes. The government official would then say, “Then you have to ask nicely from Father Fidel.” The students would say the customary line of asking for ice cream from Father Fidel, even if he wasn’t present. Then they were given the ice cream. The point was to ingrain in the minds of little children that anything they wanted, they could have, if they asked their Father Fidel for it nicely. Pedro was disturbed by this, saying, “I couldn’t allow for my daughters to be brainwashed.”

The final incident came later, and occurred at Sacred Heart, a Catholic school attended by two of Pedro’s eldest daughters.

Pedro recalls walking up to the school and seeing young communist girls guarding the grounds with guns.

“The nuns were supposed to be teaching, but they weren’t,” Pedro said. “I remember meeting a nun outside of the school and she was in tears. She said that they had herded the nuns into one room within the school only to humiliate them.”

Pedro never understood exactly what she meant by “humiliated,” but the message was clear. Fidel wanted the schools controlled by the government.

“When I found out the school wasn’t going to open…that’s when I knew I couldn’t raise my family there,” Pedro said. “I went home and told my wife to start packing.”

Photo by Rich Bodee, 14 East.

The plan was for the family to go in waves, as to not set off any red flags, but Pedro had a problem. His visa had expired and his appointment to renew it was on January 14, 1961. The U.S. and Cuba severed their diplomatic relations January 3, 1961.

“I had to get a U.S. visa through Panama,” Pedro said. “I had a client that connected me with Bobby Motta. Motta and his brothers owned half of Panama at the time. He picked me up from the airport and drove me to the American Consulate. After thirty minutes, I had a new visa, but I needed to go back to Cuba to get some things and say goodbye. All of the flights were booked, but Motta called Pan Am and I was on the first flight back to Cuba the next morning.”

Pedro had to tie up a few loose ends before leaving Cuba.

First, Pedro needed an insurance plan. He had a ring with two 3-carat diamonds that once belonged to Mrs. Cartaña, the widow of Pedro’s father’s law partner.

One night, Mrs. Cartaña and one of her adopted daughters were murdered by the caretaker of their property. In the aftermath of settling the estate, Pedro was told to pick something and he chose the ring as a keepsake.

Pedro knew that a refugee couldn’t and shouldn’t wear a gaudy, flashy ring like that around, so he came up with a plan. He had a client who owned a shoe factory who helped him hide the ring for safekeeping by crafting a small compartment in the heel of his shoe.

“He put it right here,” Pedro said while pointing to the heel of his shoe.

Later, Pedro replaced the diamonds with pearls and made two rings, one for him and another for his wife.

Photo by Rich Bodee, 14 East.

A few days before Pedro left Cuba, he went to speak with his father. When Pedro told him of his plans to leave, Alfredo thought he was being acting prematurely.

“My father was really taken with my decision to leave,” Pedro said. “The next time I saw him was 15 years later in Mexico City. You can imagine how hard that was for me, but he knew I was right for leaving… after a while.”

Pedro didn’t want to give the impression that he and his family were fleeing, so before he left, he paid the maids in advance and told them he and his family were going on “a long vacation.”

“When we left,” Pedro began. “We kept saying we would be back in six months or a year, but we never went back. My wife, Gloria, still says, ‘You could give me a million dollars and I still wouldn’t go back.’”

Pedro’s goal became to make a new life for his family in America. After fleeing Cuba, the Portelas initially stayed at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach because Pedro had a connection there. Subsequently, Pedro rented a house in Miami while he performed odd jobs for money. He recalls interviewing for a job as a room clerk at a hotel in Miami.

“The job was seven days a week, the hours were 12 a.m.-12 p.m., and the pay was $200 a week,” Pedro said. “I was hungry, but not that hungry.”

Pedro’s frustration grew the more the realization hit him that while he had been a prominent lawyer in Cuba, he was insignificant in America; just another face in the crowd.

Eventually, Pedro moved to Chicago where he got a job as a legal editor with Commerce Clearing House. The company published weekly tax reports and facilitated joint ventures with Latin American countries, the biggest of which was with a Mexican company. He rose through the ranks at CCH and eventually became Vice President before taking an early retirement in 1992. He and Gloria would spend their summers in Chicago and winters in Key Biscayne before moving down to Key Biscayne full-time in 2007. In 2012, the Portelas moved to Houston to be closer to two of their daughters.

As for Palmas Gemelas, according to a lifelong friend of Pedro’s who visited Cuba in the early 2000s and was able to locate the property. In its allegedly decrepit form and utter state of disrepair, it became a shelter for unwed mothers. Hotel Varadero Internacional is a different story. In a post on TripAdvisor.com, the hotel closed its doors on January 1, 2015.

In March of 2016, CNN published an article about Gary Rapoport, the grandson of Meyer Lansky. In the article, Rapoport insisted the Cuban government owes his family for the businesses Lansky owned when they were seized by the Castro regime. In fact, a Cuban attorney named Pedro Freyre was also cited in the article agreeing with Rapoport and added that, “The Cuban government owes roughly $8 billion to U.S. individuals and companies who had their assets taken.”

Individuals like Pedro, but when I asked him about this, he just rolled his eyes.

As Pedro sat in the sun on the 7th floor terrace of his apartment building in Houston that overlooks The Galleria, he donned his ring that he smuggled in his shoe as an insurance policy and he was wearing a guayabera, a traditional Cuban shirt. It was clear to me that he still longed for the shores of Varadero, even before he showed me his secret stash of Cuban cigars.

“I would love to go back there,” Pedro said. “But I don’t want to go on a ‘Disneyland version,’ you know, the bulls–t cigar tours or anything like that. If I could have my own driver and go where I wanted, I would go.”

By the manner in which Pedro spoke, by the slight tilt of his head when he thought of Havana and Varadero, and by the way he laughed at some of the old memories of the Cuba he once knew, it was clear to me that what may remain of the Cuba as Pedro once knew it, still beckoned him home.

But, regrettably, Pedro never made it home. On Aug. 20th, 2018, Pedro died of complications from a stroke he suffered. He was 89 years old. He is buried in Houston, over 1,200 miles from Cuba.

Header photo by Rich Bodee, 14 East.

NO COMMENT