Kim Wasserman was inspired throughout her life by the relentless strength of her mother — one of the first Mexican steelworkers to join a union on Chicago’s Southwest side — in a vibrant Mexican-American neighborhood called Little Village.

It wasn’t until her three-month-old son suffered an asthma attack that she would have to channel the strength she learned from her mother in order to fight for her community’s right to breathe.

After Wasserman’s son was diagnosed with asthma she started to notice that other children and family members in her community struggled with the same condition. She began to wonder if the two large coal power plants that surrounded her home had something to do with this recurring trend.

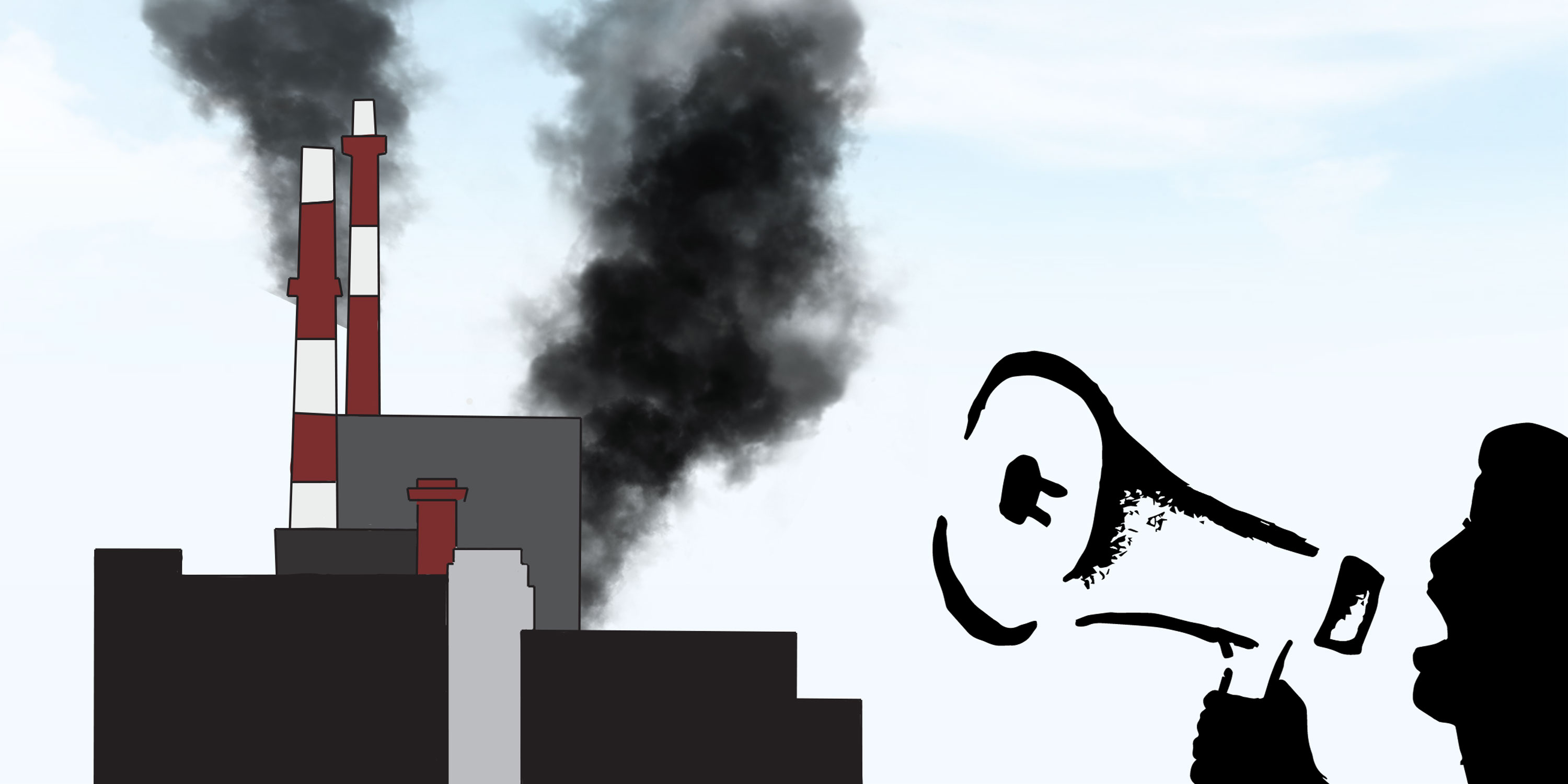

Once symbolic of industrial growth and economic prosperity in Chicago, the Crawford and Fisk coal plants became more recently known as the dirtiest industries in the city, especially for the communities that bear the wrath of their toxic fumes the most.

In fact, asthma, obesity, teen birth, and poor mental-health rates in Little Village are among the highest compared to the rest of Chicago. Additionally, many adults lack access to health care coverage, with 34 percent of adults living without health care coverage.

“Environmental racism looks like having a coal power plant that can run without worrying about who it’s impacting. Environmental racism looks like having the youngest Hispanic community in Chicago and not having any parks built in 75 years,” said Wasserman.

According to Natural Resources Defense Council, minority communities on the South and West sides of Chicago also have the greatest exposure to toxic air and other industry related health hazards.

Wasserman, now the executive director of the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO), worked tirelessly to bring environmental justice to her community and other affected neighborhoods by gathering together community grassroots efforts.

In 2013 LVEJO was successful in shutting down both the Fisk and Crawford coal plants.

The air became a little easier to breathe and the fear in Wasserman’s eyes became more reserved. The overall quality of life was improving in Little Village, until Wasserman and other members of her community recently began to notice an influx of diesel trucks going to the now shambled site of the former power plants.

One sunny afternoon in the fall of 2018, Wasserman got a call from her alderman telling her that Hilco Global would now redevelop the former coal plant site into a massive industrial warehouse.

“You went from shutting down a coal plant, to building a new plant on top of it. When I talk about the city of Chicago not giving a [care] about black and brown lives, this is what I’m talking about,” said Wasserman.

Little Village, among many other South Chicago neighborhoods such as McKinley Park, Pilsen and Brighton Park, is surrounded by the South Branch industrial corridor, which has been the hub of dirty industries such as coal plants, manufacturing plants and other industrial facilities that have had a lasting imprint on the communities they surround for many years.

Thanks to grassroots activism and push back from community members, the dirty industries that have historically resided here have weakened due to an increased awareness regarding the health and environmental risks they pose.

However, the new development is part of the Industrial Corridor Modernization Plan, which aims to reinforce industrial corridors in Chicago. This poses a great threat to South and West Side communities like Little Village, where the most polluting industries have tended to settle.

Wasserman wonders why she and her community aren’t given the rights and luxuries that other communities in Chicago are given without even having to try. She daydreams about the people in her neighborhood having the opportunity to earn jobs that they actually like, not just those provided by the dirty industries that entrap the community. Wasserman sees her community’s love for gardening and urban agriculture, yet, those types of careers are not what is expected of them.

“I was told that we can’t get a park, or we can’t get a shutdown, that we can’t have sustainable jobs. Why? Because we’re women, because we’re poor, or don’t have a college degree…we don’t know,” she said.

Wasserman said that she has had to push back hard against that narrative and fight for the opportunities that she has seen others grasp much more easily.

Frustrated with the politics of the City, Wasserman has long felt neglected by those who are supposed to protect her community.

“We are community scientists,” she said. “We can make good decisions about what should and shouldn’t be happening in our neighborhood.”

Recalling a photo that she found of her mother sitting on a welding truck, Wasserman is reminded of the confidence, strength and drive that her mother has instilled in her from a young age.

“People right now do not have the ability to decide what happens in their community,” she said. “But we are slowly changing this, and will continue to.”

Header illustration by Natalie Wade, 14 East.

NO COMMENT