Frankie Pedersen’s time at DePaul University was what anyone would expect from a four-year college career. She juggled classes with an internship and spent the rest of her hours at the theater school or at rugby practice.

But there has always been a part of her identity that was neglected by the university and society overall. She wears this identity proudly, sporting Native-designed red and yellow beaded earrings, her hair woven into two braids and a “You are on Native Land” pin from Urban Native Era, one of her favorite Indigenous shops, on her backpack.

Pedersen is Listuguj Mi’gmaq First Nation of Quebec, making her one of the 0.1 percent of Native American students at DePaul University.

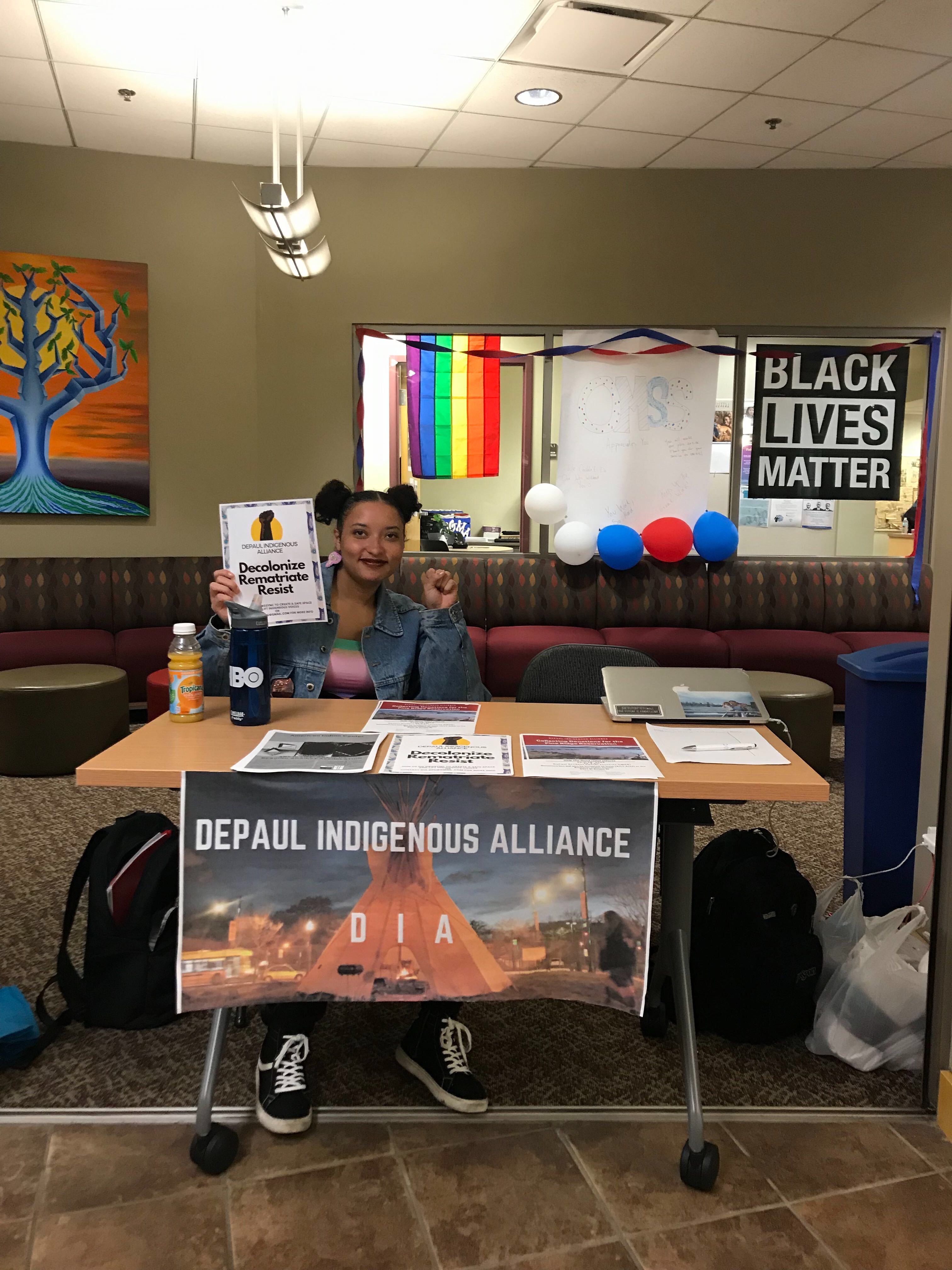

Pedersen, who graduated in June 2019, spent the past four years feeling like she did not have an Indigenous community at DePaul until her senior year. Pedersen and close friend and Native American student Naomi Turner co-founded the DePaul Indigenous Alliance.

“There are Native people here, and the second that me and Naomi teamed up we found more Native people here who have been flying under the radar because they haven’t had any place to go,” Pedersen said.

“There are a lot of Native people in Chicago and it’s just crazy to think that people are like, ‘Oh, Native people aren’t here,’ because there’s a lot and they have been here for a long time,” she said.

Pedersen remembers a time before she came to Chicago, where she had lost her connection with the Native community. Though originally from New York City, Pedersen and her family moved to New Orleans during her freshman year of high school. She vividly remembers that, while there are three recognized tribes in Louisiana, there were no local organizations that she knew of in the city. It became clear to Pedersen and her family that unless you had connections in the area, you were not going to find an Indigenous community on your own.

That is why finding a college that recognized and had resources for their Indigenous student body was an important factor in Pedersen’s decision making. So was having a top-tier theater program.

“If I weren’t doing theater… or not applying for a competitive program… that 100 percent would have gone into the decision-making process.”

In the end, the theater program won.

Photo courtesy of Frankie Pedersen.

Even though finding a strong Indigenous community after high school took a backseat to a top-tier theater program at DePaul, Pedersen still hoped that college would present the opportunity to reconnect with her Native identity after spending four years without nourishing it.

“Across all Indigenous communities, community is a main value,” she continued. Having a community helps people feel recognized. Recognition, as well as space, are what Indigenous communities across the United States and Canada have fought to achieve for centuries.

Both, however, have been denied; first by the first settlers, then by colonies, then by governmental bodies. As a means of gaining land to govern, the U.S. ratified more than 370 treaties with Native American tribes, promising to exchange territory for rare goods and products. The majority of these treaties were broken by the U.S. government, leaving Native people without any land, bargaining power or ability to survive. Many Native tribes were left unrecognized by the government, which led to immense poverty rates, legal vulnerabilities and no power in dictating their people’s future.

Still fighting centuries-old colonial structures, many Indigenous groups are forming movements dedicated to having the U.S. government acknowledge their existence and their rights over their lands. For Pedersen, she sees theater as a means of accomplishing this right.

“Before plays, land acknowledgements should be as normal as, turn off your phone before the show and your exits are here, and also you’re on Native land! Okay, enjoy the show!” she said. And this is just the beginning.

Pedersen strives towards directing plays that are by, for and about Native people. Her intense love for theater has found an intersection with her identity as a Native American woman, but it wasn’t always like this. She describes the first three years of being at DePaul as a struggle to blend all that is Frankie: her art, her political nature and her Native identity.

Each one refused to cooperate with the other, until she started spending time at the American Indian Center of Chicago, where she interned during her time at DePaul. There, Pedersen saw how all her identities could, quite simply, click.

“When you think of social justice theater, it’s hard not to roll your eyes. But looking at theater as a healing art and theater as a way to engage communities and empower communities… made me do a complete 180 and come to the realization that I can have both of these things, I have just been fighting them,” Pedersen explained.

“Across most Indigenous cultures, storytelling and performance in song or dance are very prominent across the board, really. So, theater just seems like the logical next thing,” she said.

Photo courtesy of Frankie Pedersen.

As for the DePaul Indigenous Alliance, Pedersen has a lot of hopes for her new “baby” such as hosting a powwow on campus. Since the 1800s, powwows have created a space to celebrate the cornerstones of Native culture: food, dance, music and art.

Pedersen remarked that being able to bring this vital tradition to DePaul would reject the notion that there is no Native life at the university.

“My dream is… to get successful enough for DePaul Indigenous Alliance to host a powwow!”

Header image courtesy of Frankie Pedersen.

NO COMMENT