Chicago Teachers Union walk out amid contract negotiations

As the sun began to rise Thursday morning, a teacher dressed in a bright red sweatshirt walked briskly up East Pershing Road, holding a Box of Joe from Dunkin Donuts in one hand and his dog’s leash in the other.

Nearly 30 teachers greeted him with cheers — some had arrived at Wendell Phillips Academy High School’s picket line as early as 6:15 a.m. and they welcomed the caffeine. The educators stood near the curb holding picket signs that read, “Parents educators students together,” and, “On strike for my students.” When cars honked as they passed by, the educators cheered.

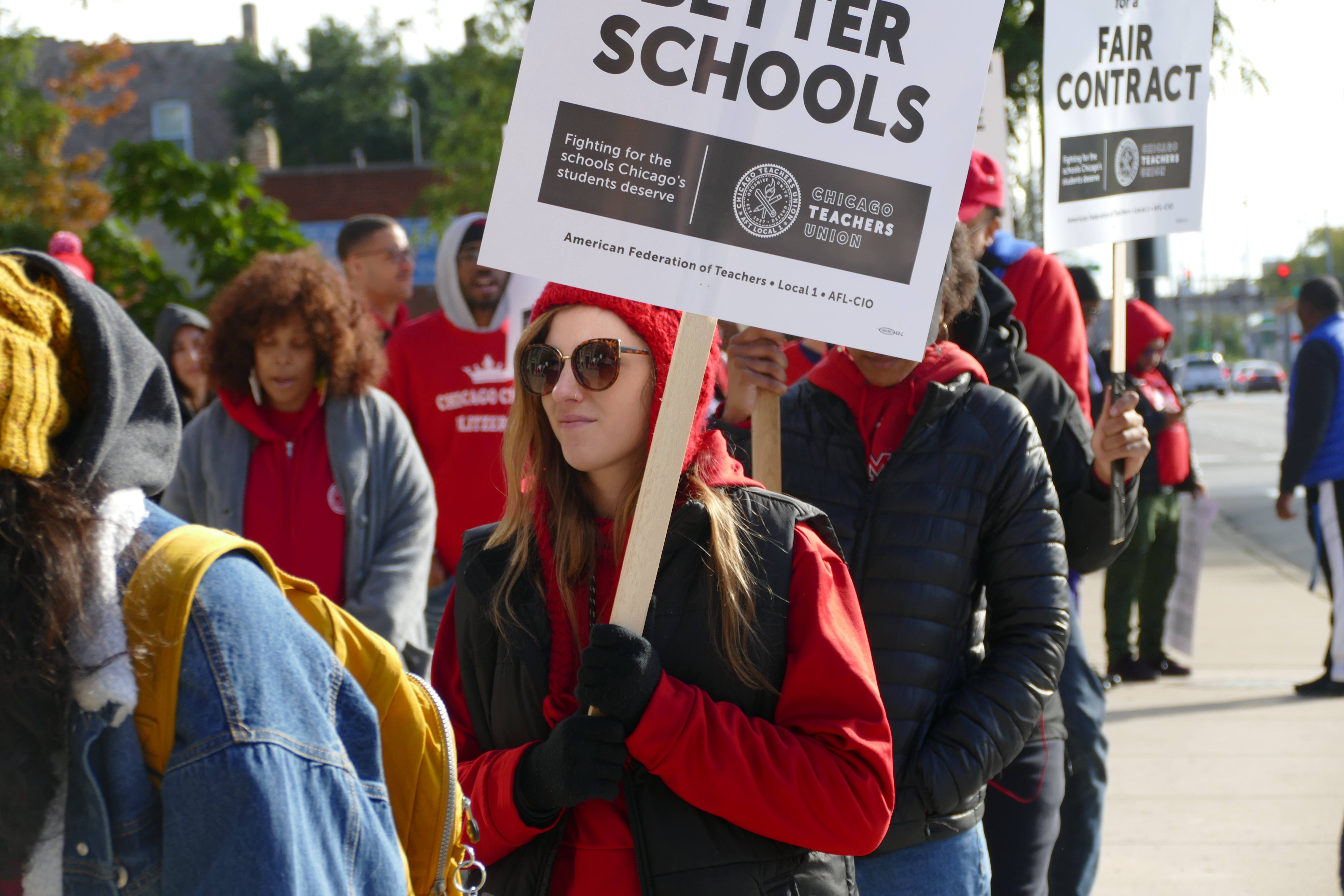

Wendell Phillips Academy High School educators at the picket line. Photo by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

It was day one of of the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) strike.Though they gladly stood outside during the wee hours of the morning for their students, they hoped the strike wouldn’t last long.

“My hope is that both sides can come to a resolution of the impasse and that we can get back to work,” said William Hendrickson, a civics teacher at Phillips Academy. “I think pretty much all of us do.”

Other teachers on the picket line echoed Hendrickson’s sentiment — they’d much rather be inside the building with their students teaching. However, they said their students deserve better and at minimum they deserve equal to what students in more affluent areas like the North Side have. They deserve more nurses, school psychologists, social workers, librarians and affordable housing.

And for that, they would strike.

The teachers at Phillips Academy were not alone. Thousands of Chicago Public Schools (CPS) educators, including roughly 25,000 CPS teachers and 7,000 support staff workers, hit the picket lines at Chicago’s more than 600 public schools. While negotiations made progress leading up to the strike, the city did not meet the demands of CTU.

Among the top issues are more equitable staffing (including social workers, librarians and nurses in schools and lower caseloads for counselors), extending to compensation, paid prep time and capped class sizes.

Prior to the strike, Lightfoot proposed an offer, including a 16 percent raise over five years — compared to the CTU’s request for 15 percent for three — and a small increase to health care contributions. Lightfoot and her administration had also verbally committed to adding 250 nurses, 200 social workers and more special education case managers to schools; however, they said they wouldn’t write it into the contract due to fears that it would limit their flexibility.

This offer didn’t satisfy the union’s demands. On Wednesday, CTU solidified their plans to strike.

CPS canceled classes on Thursday for its over 300,000 students. The school buildings remained open and minimally staffed for students who needed a place to go during the day, and offered three meals for the students who rely on school lunches. Throughout the morning, a handful of students entered Phillips Academy.

Equitable Resources

By 8 a.m. — around when school would have started — over 50 educators had arrived at Phillips Academy. Some came bearing signs they made, while others grabbed signs left for them at the picket lines and wrote their own words in Sharpie on the bare side of the poster. One man used a rope to tie a stainless steel soup pan around his body. As cars drove by he used the pan as his drum.

History teacher Colin Gaw and science teacher David Wilson stood near the curb.

“There’s a long list of issues,” Wilson said. “I think this year we’re focusing on things like class size and getting nurses for our students to take care of their health when they’re here and to get a social worker.”

These are resources that teachers say Phillips, and many other schools primarily on the South and West sides, are disproportionately in need of.

“Kids at Phillips don’t get the same resources that I, a middle class white person, got in High School,” Gaw said. “I have a diabetic student who doesn’t have a school nurse. I’m diabetic so I can give her advice, but that’s not fair and it’s not just.”

Multiple teachers mentioned instances in which their students needed to access a nurse, but weren’t able to because a nurse wasn’t working that day.

“Students can’t focus in class if they don’t have their primary needs taken care of,” said Cristina Vasquez, a school counselor. “If a student’s really struggling through something, they can’t just sit in class and pretend they care about math.”

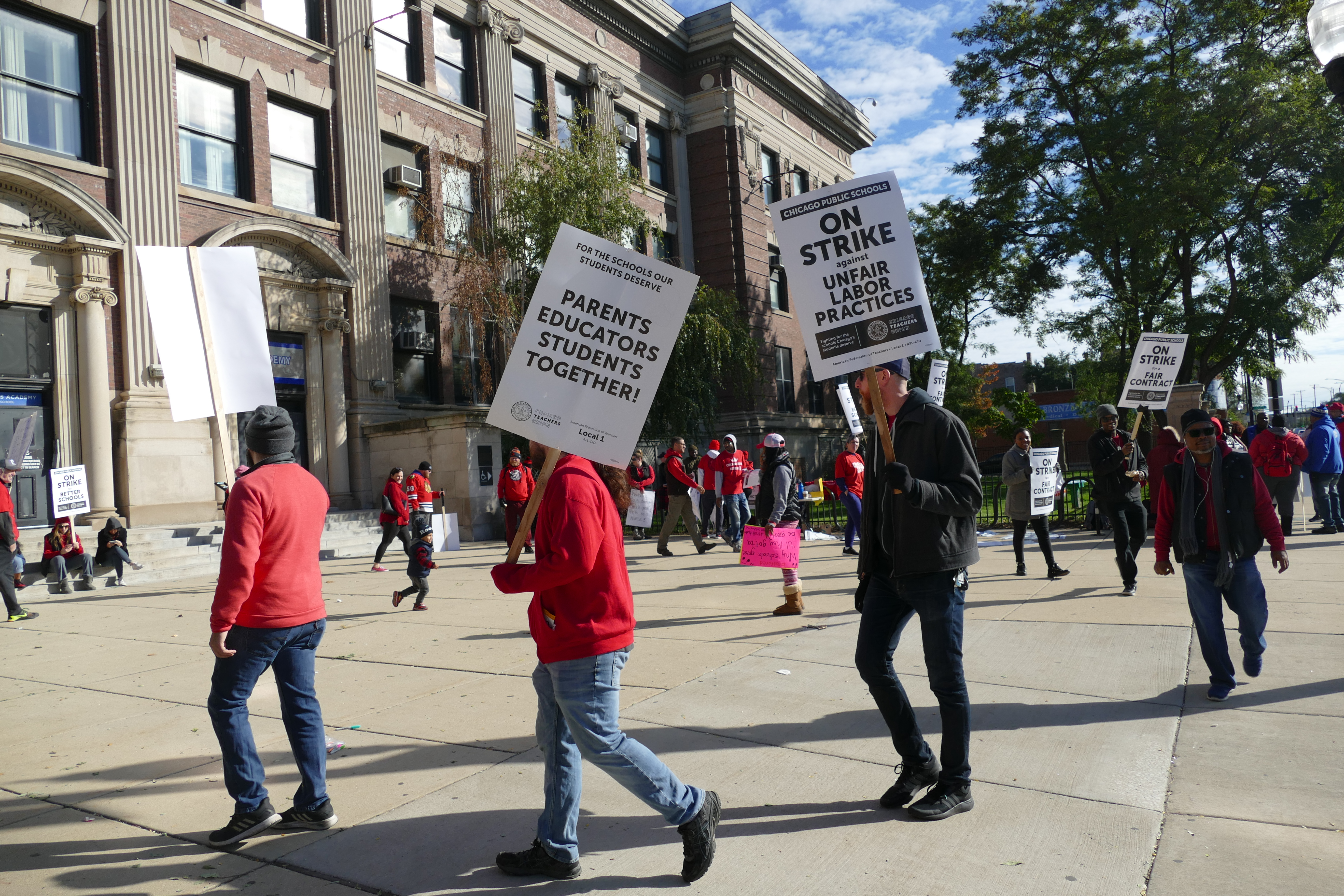

Photos by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

In addition to staffing demands and class size limits — some say schools on the South Side have seen kindergarten classes with up to 40 students — affordable housing is also a core demand.

“Here we have a pretty large housing-insufficient population and so I know that having somewhere for all of our students to be able to afford to live would be lovely,” said Shanna Pierce, a high school math teacher at Phillips Academy. “It would help their education because they wouldn’t have to worry about that.”

This is the first contract negotiation in which the union has called on the city to address housing inequity, which has historically plagued many disinvested neighborhoods on Chicago’s South and West sides. During the 2018-2019 school year alone, more than 16,000 CPS students experienced housing insecurity, according to the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless.

Cynthia McCullough, a school counselor, said affordable housing programs would relieve students of some of the stress they might experience while in school.

“We have a lot of students who are in class hoping and wondering if they can eat at night, if they’re going to be able to get the clothes or be able to buy the uniform that they need, be able to do what it takes to be successful in class,” McCullough said. “They’re also figuring out how they can help their parents with the bills.”

Illinois law largely restricts issues teachers can strike about to pay and compensation issues, and it’s unclear how affordable housing might be situated in the union contract.

Around 9:30 a.m., educators from an elementary school down the street visited Phillips. They rolled with them a medium-sized square speaker strapped onto a metal dolly. As “Ain’t No Stoppin Us Now” by McFadden and Whitehead filled the picket line with rhythm, their chants turned into cheers. One by one the educators began doing the Electric Slide.

Educators doing the Electric Slide to “Ain’t No Stoppin Us Now.” Photo by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

Two Strikes, One-Day Walk Out, Seven Years

At 10 a.m., as the morning portion of their strike approached its end, the educators walked in a larger circle, still chanting like they had earlier. In 30 minutes they would depart from the picket lines and meet back up at the rally in front of Chicago Public Schools headquarters on Madison and Dearborn streets later Thursday afternoon.

While the strike was new to some teachers at Phillips, it was bitterly familiar to others. Just seven years ago CTU went on strike for similar reasons: benefits and class sizes. So for a handful of teachers at Phillips Academy, this was the second time in their careers that they were striking.

“It produces a lot of anxiety in us, in our students, in everybody at work,” Pierce said. “It often makes us feel like we’re not very respected as professionals at all. Listening to the fact that we are still having some of the same arguments about contracts seven years later.”

The 2012 strike lasted seven days. Not long after, then Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced sweeping school closings, primarily on the city’s South Side in 2013. Though parents protested, fifty public schools shut down due to poor performance, under-enrollment or both — including a handful in Bronzeville.

“It’s not just about the elite schools, but it’s about all of our schools,” said English teacher Raquel Rattray. “It’s the start of something bigger and recognizing a bigger issue inside of CPS and the segregation that exists. Hopefully moving forward we can start closing those gaps.”

In March 2016, CPS teachers also went on an unprecedented one-day walk out, calling for increased state funding to CPS.

Photo by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

March For Students

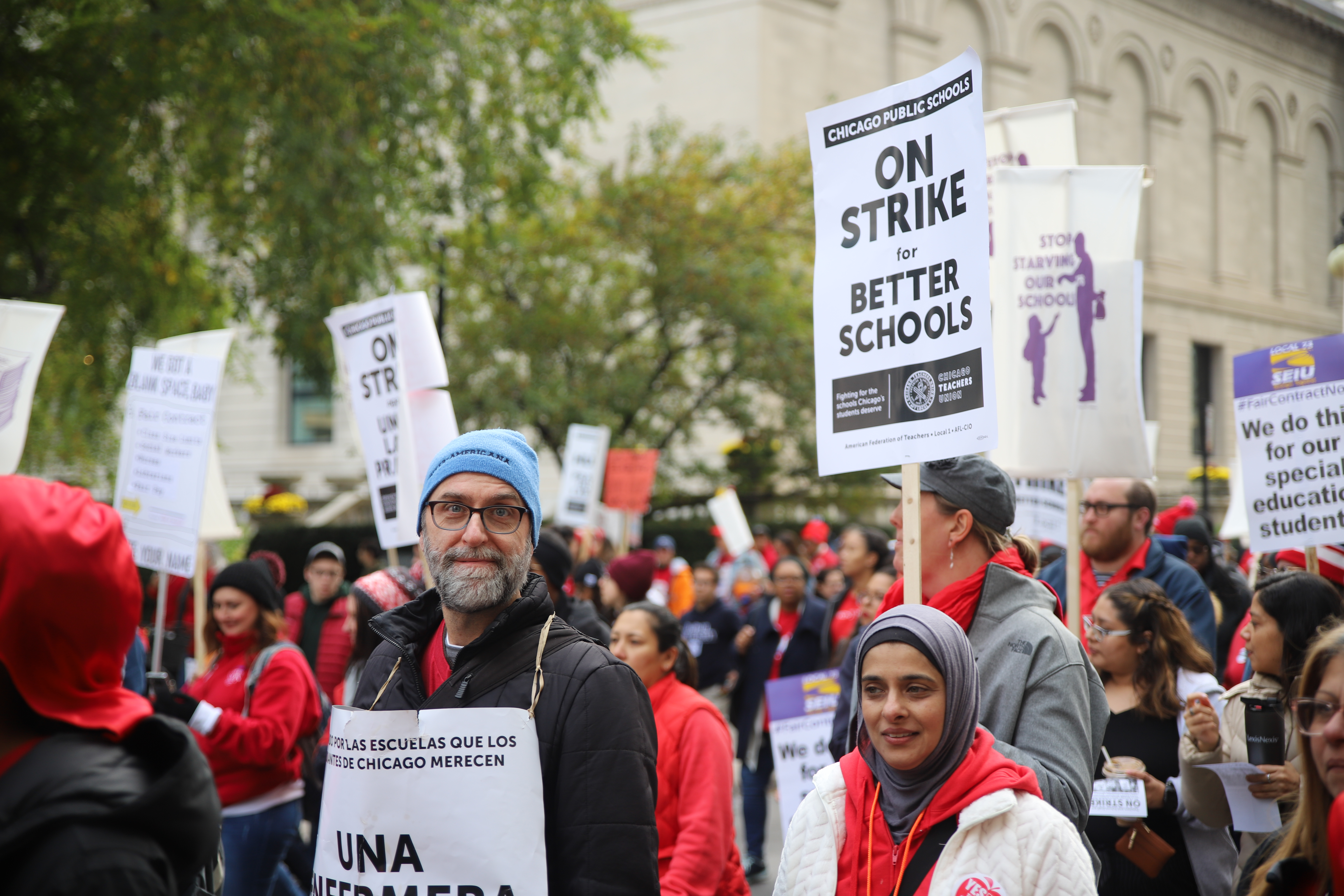

At 1:30 p.m., ten educators from Phillips walked west on Madison Street in the Loop toward Dearborn. As they crossed State Street, a sea of red clothing and white signs began to appear. Wanting to stand in the heart of the protest, the teachers carved their way through the crowd until there was no more space to move forward.

In awe of the mass attendance, which flooded Madison Street and overflowed onto Dearborn, they took pictures of the crowd and with each other. What sounded like a marching band played just 10 feet to the left, though there were too many people to see across the intersection and too many signs held in the air to see over.

Ten of the educators from Phillips Academy at the rally on Thursday. Photo by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

While waiting for the march to begin, the teachers wondered how long the strike would last, and repeatedly refreshed news pages on their phones to see if any progress had been made. They noticed a helicopter above and searched local stations’ social media for livestreams of the strike from a bird’s-eye view. For many of the teachers, this was their first teachers strike, a serious event in which the end result will affect children across the city. The gravity of the rally also evoked excitement and pride — this was bigger than them.

Nearly an hour later, the rally began moving north on Dearborn and the chants began.

“Our streets, our schools,” the crowd shouted. Eventually they marched to Grant Park, closing Michigan Avenue from Jackson Boulevard to Monroe Street.

Despite Thursday’s protests and more negotiations, no deal has been made. However, CTU President Jesse Sharkey said there has been progress — they received a written contract offer for class size Thursday morning. The teachers will continue striking until an agreement is reached. CPS classes, and weekend sports activities, are canceled until the strike is over.

Lightfoot has said that the strike was avoidable, saying CTU should have acted more urgently and increased bargaining days as the strike drew near.

“We would all love to be in the building today doing work,” Vasquez said. “To be out here striking isn’t necessarily what we want to do, but it’s what we have to do.”

Photos by Chris Silber, 14 East

Header image by Marissa Nelson, 14 East

CTU Strike Daily Coverage: What’s Happening at the Picket Line – Fourteen East

21 October

[…] out her Twitter coverage and read her full story about the Phillips educators’ first day on strike. Below is a brief recap and record the people involved in the […]

CTU Strike Day 12 – Fourteen East

18 November

[…] Thursday, October 17, CTU members went on strike over contract negotiations for a variety of reasons — issues topping the list were overcrowded classes and a need for more […]

CTU Strike Coverage Day 13 – Fourteen East

18 November

[…] Thursday, October 17, CTU members went on strike over contract negotiations for a variety of reasons — issues topping the list were overcrowded classes and a need for more […]

CTU Strike Coverage Day 14 – Fourteen East

18 November

[…] Thursday, October 17, CTU members went on strike over contract negotiations for a variety of reasons — issues topping the list were overcrowded classes and a need for more […]