The year is 2007. You’re a white, male 18-year-old moving out of the house and starting his first year at college. You are decorating your dorm room, doing the most to make it look “cool” (whatever you define as cool). You decide to buy a poster. You decide to get one of your favorite films. You settle on either a Fight Club or Pulp Fiction poster. It hangs on your wall and follows you from residence to residence.

Fight Club (David Lynch, 1999) and Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) are somewhat of a joke. Not in the sense that their content is bad or poorly made, but mostly in regards of their association with “film bro” culture. You know the type. He leans back in his chair, baseball hat backwards, and talks endlessly about how David Lynch’s Blue Velvet reinvented the noir genre. Be careful about what movies you talk about around him, because if say one inkling of good word about a film like Mamma Mia! or The Avengers, he’ll rant about how Hollywood prostitutes itself for the sake of making money, not art.

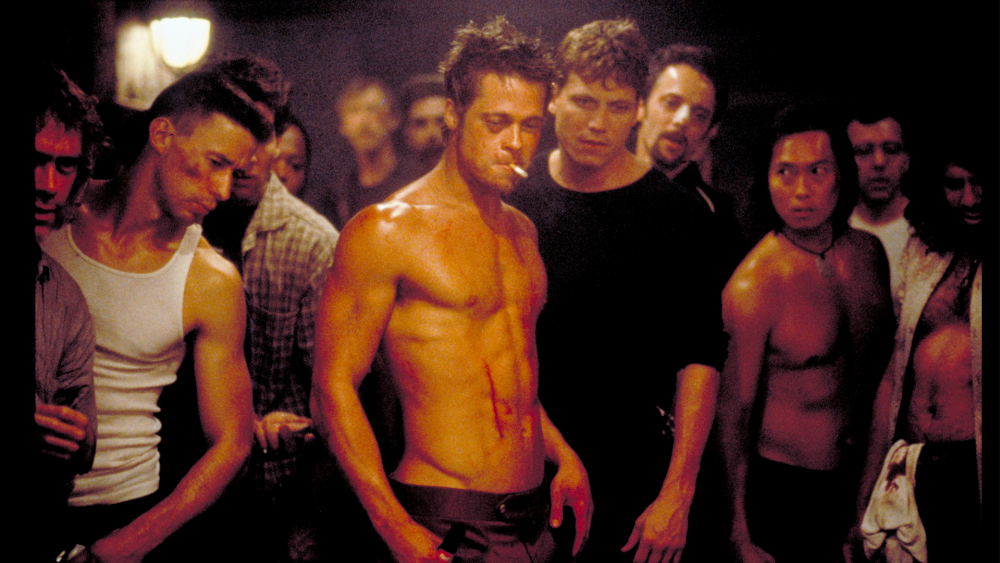

Walk into any frat house, freshman boy’s dorm room or a 20-something’s apartment — and there’s bound to be a poster for Pulp Fiction or Fight Club, haphazardly taped to the wall. These movies stand for something: fraternity, masculinity, anarchy; wielding violence as a red-hot fever dream of the future.

There’s an edge of coolness, especially in Pulp Fiction. The snappy suits and nothingness dialogue that weave through criminal Los Angeles and make its underbelly look so hot. But these films are objectively okay. They are not terribly riveting pieces of art. They lean heavily on aesthetics, but end up creating a world that has very little substance amongst its stylings.

For example, the film Love, Actually (Richard Curtis, 2003) is a vignette-style film, exploring different examples of love over the course of the five weeks leading up to Christmas. It is the clean-cut sister of Pulp Fiction, another vignette-style film. But one is degraded as fluff, because it is a “romantic comedy” and aimed at women.

I would like to argue that Pulp Fiction is a story about nothing. It’s a character study of how people interact with each other. It has the same weight as Love, Actually, but because of its producers (hello, Weinstein brothers!) and writer/director, there’s a sense of legitness to it. Any film bro will enthusiastically tell you that Tarantino insisted on strangling Diane Kreuger’s character in Inglorious Basterds. Pulp Fiction is a legit piece of art because in the marketing process, the producers told us it was art. We were sold a story about nothing, and believed it was the greatest, most important one ever told.

Fight Club is the weird cousin of Pulp Fiction. They both live in the same universe of Film Aesthetics™, but Fight Club is for the masses. It was a book to begin with, written in 1996 by Chuck Palahniuk. David Fincher picked it up and turned it into a Disneyland for masculinity. Everything about it is snappy and quick, the whole film is action driven, culminating in explosions galore.

Photo courtesy of 20th century fox.

The thesis of Fight Club is much stronger than Pulp Fiction’s, we get a strong sense of the capitalist struggle Edward Norton’s character is under. But, once again, everything is lost in its stylings. The coolness is laid on thick, making this lifestyle an aspirational one. Isn’t Tyler Durden so cool with his red leather jacket? Isn’t his rock star, devil-may-care attitude so sexy? He is the antagonist of the film, and yet he’s framed as somewhat aspirational. We can make antagonists as cool and compelling, but when they distract from the point of a story, what is the meaning of having them there?

I’d like to take this moment to take a slight pivot and talk about a film that uses aesthetics well and in a way that emphasizes the thesis of the piece. Trainspotting (Dir. Danny Boyle, 1996), while very similar in theme to Fight Club and Pulp Fiction, uses aesthetics in a way that doesn’t distract from the themes, but enhances them.

Trainspotting is a character study of a group of friends living in Edinburgh. They exist in post-Thatcher times, trying to survive in a world that is focused on material goods and status. They shoplift, do drugs, go to clubs, do everything they can to disassociate from their world. Trainspotting uses magical realism in a way that physicalizes the disjointment our heroes feel. Mark loses some heroin while he uses “the worst toilet in Scotland.” He fishes around through the dirt, eventually diving into the toilet bowl itself and swimming in its water. He leaves, covered in shit, but it’s fine, because he has his heroin now.

Trainspotting, like Pulp Fiction, is a film that serves as a character study, but it doesn’t care about the slickness of its world and making its characters look great. Trainspotting is an ugly film, it celebrates its ugliness and the characters see that. And, like Fight Club, Trainspotting has a few thoughts to say about the post-Reagan (or post-Thatcher, in Trainspotting’s case) era. The ugly, gritty aesthetic of the film is rocket fuel to its thesis. We see firsthand how angry Mark and his friends feel about simply existing.

There is nothing cool about being addicted to heroin.

Fight Club and Pulp Fiction are these strange gatekeepers to the world of film, but at what cost? Because a few angsty white men decided these films were the gold standard, there is no room for anything that is different. These “film bros,” while being annoying and fun to make fun of, are holding onto an idea of what film should be. They dictate what is art, which is impossible to dictate in the first place. Women and people of color are notably absent from these films (Pulp Fiction has two female characters, Fight Club has one). When they are present, they are treated as objects, as punching bags, as things that overdose on cocaine and need to be saved.

Fight Club and Pulp Fiction are still part of our cultural dialogue around art and aesthetics. We won’t be able to shake them, not for a long time. They are the “cool kids” of film. People look up to them as icons of the industry, as shining beacons of artistic genius. They’re slick and sexy, but at what cost? The dazzle of Pulp Fiction distracts us from its non-existent story and the coolness of Fight Club warps the message of the film. They are the dangers of aesthetics, those being the only reason these two films haven’t faded into obscurity. Under the surface, there is nothing to them, only shells of what they want us to see.

And we fell for it.

NO COMMENT