Spoilers ahead for BoJack Horseman. You’ve been warned.

When I started watching BoJack Horseman, I didn’t realize how much the show would end up impacting me.

It was 2014: Netflix original series were still in their infancy, and the streaming service was just starting its foray into animated programming (though now, the list is quite extensive) and I had only just started being interested in adult animated shows.

I mean, it’s cartoons for grown-ups. Why wouldn’t I spend a few hours on that?

BoJack Horseman is the story of an anthropomorphic horse in his fifties. The titular character (Will Arnett) is a washed-up ‘90s sitcom star living off the proceeds of his one hit show, which is basically this universe’s version of Full House.

Like many animated series, the show started with hijinks more than anything else. BoJack gets into an argument with Neal McBeal, the Navy SEAL, (played by the wonderfully funny Patton Oswalt) who just so happens to be an anthropomorphic seal, about a box of store-bought muffins. The argument escalates to the point where they are on a split-screen newscast yelling at each other about whose muffins they really were.

BoJack and Neal argue on “MSNBSea,” Season One, Episode Two, “BoJack Hates The Troops.”

BoJack throws outrageous parties, he makes questionable drunk decisions, he argues with his agent — who also happens to be a cat and his ex-girlfriend — and he accompanies his ghostwriter to Boston to go to her estranged dad’s funeral, only for her brothers to turn her father into chum to “throw in Derek Jeter’s stupid face.” The show captures a delicate balance of ridiculous shenanigans and dark themes, all shown through the deep and evolving connections between the main characters.

The relationship that is central to the show is the one between BoJack’s ghostwriter/biographer, Diane Nguyen (Alison Brie), and BoJack, developed beautifully over the course of six seasons. In the beginning of the series, Diane is brought in to ghostwrite BoJack’s memoir, but as the show progresses, so does their relationship.

Diane soon becomes BoJack’s closest confidant, and at first, this seems to make sense. Diane and BoJack both display the same nihilism and depression, a feeling of being directionless the main source of their pain as the show goes on. Diane goes on to get married only for her marriage to dissolve by the fifth season; BoJack starts the series by getting dumped by his girlfriend of seven years and goes on to have many failed attempts at relationships with women.

However, soon enough, the differences become clear between BoJack and Diane. Diane is a staunch feminist and actively trying to be a good person. BoJack seems to be happy continuing to suck people into his darkness. Their relationship turns into a system of interconnected roots and branches, like two trees growing and twisting together. I’m still not sure if their friendship was good for either of them.

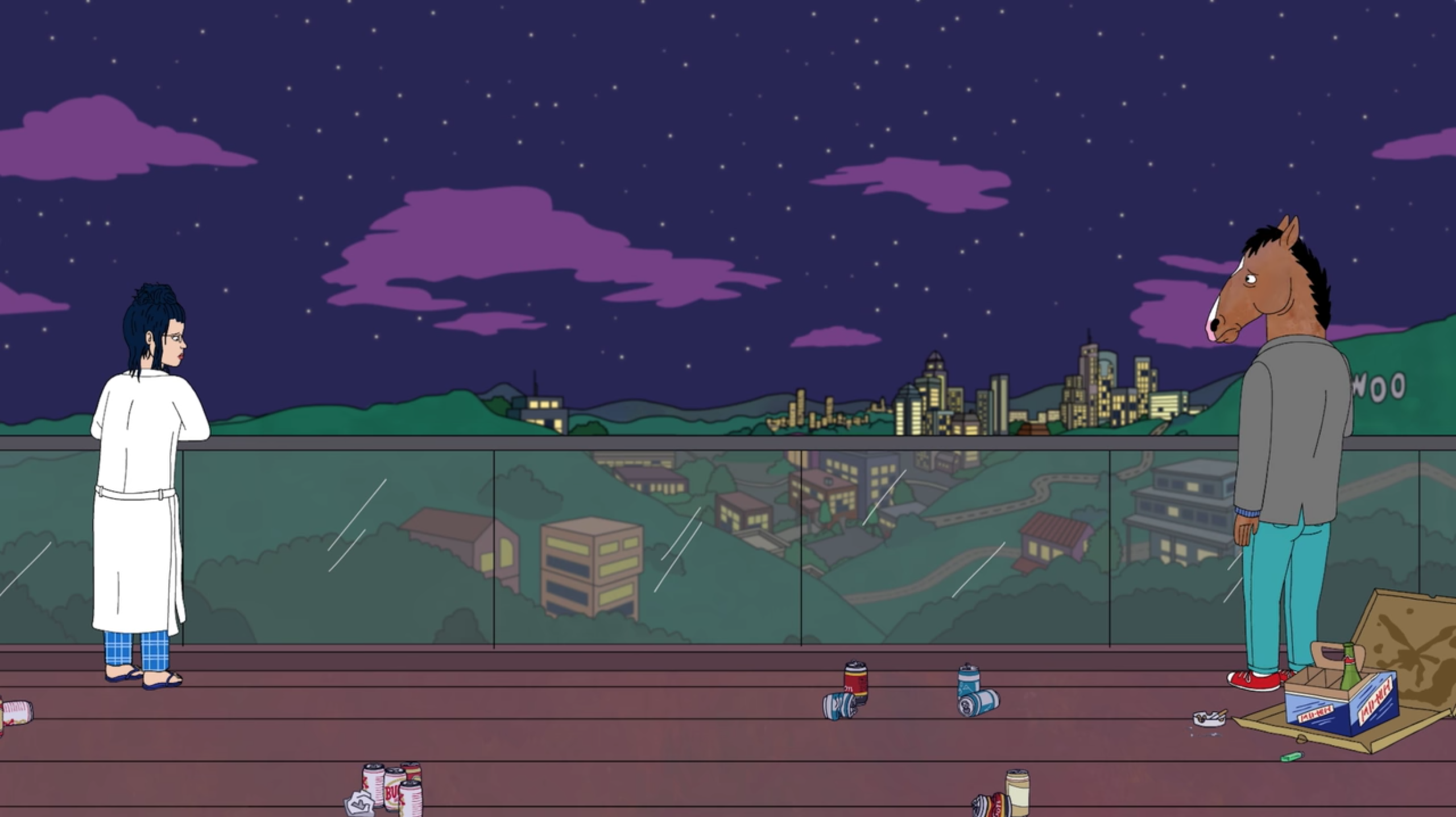

I argue that the show doesn’t start with the first episode, but instead at the end of the second because of this. The second episode sees BoJack spending the entire episode avoiding talking about the truths of his life so Diane can write her book, but at the end, they have a touching conversation on the roof of Diane’s home that sees BoJack finally opening up about his abusive parents, his problems with substances and his problematic behavior. Diane empathizes with him; she sees herself in him. This scene kicks off their relationship, centering these two characters.

BoJack and Diane on the roof of her home the first time they truly connect, Season One, Episode Two, “BoJack Hates The Troops”

As the show goes on, Diane, who started as a passive observer of BoJack’s life as his biographer, takes on a more active role as his friend. Their friendship is tumultuous. The end of the first season sees Diane and BoJack clash over the way she wrote the book about him. The second season shows her as a character consultant on the prestige film that BoJack is starring in because of that very book she wrote—though, as BoJack sharply points out, she never apologized for hurting him at the end of the first season.

BoJack is the kind of character that holds grudges; he gets angry over little things and he lets that anger fester inside him. He still hates Diane’s boyfriend and later husband (and even later still, ex-husband), Mr. Peanutbutter, for starring in a sitcom that ripped off the concept of his own. He gets overly upset any time there’s honeydew melon in a fruit salad. He’s never quite forgiven himself for getting his best friend fired from his hit television show.

Diane’s tendencies run in similar ways. She bottles up her emotions until they explode and she gets angry over little things that go against the idiosyncrasies she holds onto tightly. BoJack has an inclination towards escape—in his case, through substance abuse—whenever things get difficult. She runs away from her problems.

Midway through the second season, Diane starts entertaining the idea of writing a book about the bombastic philanthropist Sebastian St. Clair (Keegan-Michael Key) and spending months in the fictional war-torn country of Cordovia. Diane is so sure she wants this that she very nearly blows up her marriage to get it—though, in all honesty, that marriage was already in steep decline by the time she leaves.

BoJack and Diane reunite after BoJack tries to escape his problems by leaving Los Angeles, Season Two, Episode 11 “Escape From L.A.”

After realizing that spending her days in a refugee camp is too much for her, she returns to Los Angeles and is unable to return to Mr. Peanutbutter. She lives with BoJack instead, spending her days passed out next to his pool with a bottle of bourbon and dragging him down into the same behavior she used to call him out for. Diane’s marriage survives this, surprisingly. BoJack’s relationship with his girlfriend doesn’t.

Perhaps the most telling moment in their relationship is when they’re talking about BoJack’s fifth season acting project, Philbert, which follows the vein of shows like True Detective in following damaged detective John Philbert. Diane is a consulting producer on the show, there to make the show less problematic, though that doesn’t quite work—John Philbert is still a toxic character.

BoJack and Diane argue outside of the premiere of BoJack’s new show, Philbert, Season Five, Episode 10, “Head In The Clouds.”

Diane gets frustrated with this, and she ends up getting into a heated argument with BoJack about the meaning of the show. She calls out the audience in a meta way; she says that using a toxic character to justify our own toxic behaviors is not the point of shows with flawed main characters. It’s jarring. You realize with a jolt that as much as we empathize with BoJack, we have to remember that we cannot allow his behavior to make ourselves feel better about all the times we’ve hurt those in our lives. We cannot be casual bystanders.

Our complicity in idolizing these men is what BoJack forces us to grapple with. Hollywood allowed these abusers to go unchecked, all the while feeding us television and movies about flawed male characters whose flaws really turn out to be abusive behaviors. I had always felt a little guilty about loving BoJack Horseman so much for that very reason, but at the last second, BoJack flips the script.

BoJack gets into an argument with journalist Biscuits Braxby as she confronts him with his abusive behavior, Season Six, Episode 12, “Xerox of a Xerox.”

In a telling interview with a TV journalist, the anchor unravels the timeline of BoJack’s past relationships: all of them are with young women, usually women he had professional or personal power over. In the context of the show, the slow build-up of BoJack’s toxic behaviors and display of his inner struggle causing them makes sense to the viewer.

We’re taught to empathize with him, and the middle of the sixth season tends to make me feel a bit sick to my stomach. Dealing with the idea that this main character, deeply flawed but lovable all the same, is also an abuser and deserves to face consequences for his actions is difficult to swallow. By the latter half of the sixth season, BoJack is sober, teaching drama at Wesleyan and functioning without hurting the people around him. He’s shown growth. He’s faced a personal reckoning for the things he’s done.

However, even with that personal reckoning, the other shoe had to drop. His fall from public grace and later imprisonment—14 months for breaking and entering, though, as BoJack put it, it was “kind of for everything”—reminds us of the fact that even though we have seen BoJack’s personal growth, he owes it to all the people he hurt over the course of the show and before we met him in the pilot.

These consequences are often missing in real life. Woody Allen, while losing much of his cultural significance, still hasn’t faced trial. Kevin Spacey’s lawsuits are getting dropped left, right and down the center. Harvey Weinstein’s trial exploded with damning testimony, but for years, his abuse was covered, partially thanks to once-feminist icons Gloria Allred and Lisa Bloom. For a feminist like myself, the #MeToo movement’s future seems bleak.

BoJack Horseman shows us, in its typical serious-yet-tongue-in-cheek fashion characteristic of the show, how it should be. BoJack deserved to face consequences for his actions. His behavior on the show included choking a costar, getting a teenage girl drunk, almost sleeping with his friend’s teenage daughter and supplying the drugs that resulted in the death of his young former costar, Sarah Lynn. He needed to face a comeuppance for that, even if it’s as half-hearted as imprisonment for another, lesser crime.

We got too invested in his pain; we forgot everyone else’s.

BoJack’s life falls apart by the end of the show, but it’s not entirely bitter. The series finale shows happy endings for all the peripheral characters… just not BoJack.

Somehow, this feels both like vindication and heartbreak.

That ambiguity is perfectly summed up in the final scene of the final episode, which finds Diane and BoJack, after over a year of not seeing each other, on the rooftop, smoking a cigarette. The scene is incredibly familiar; it mirrors the rooftop scene from the first season.

At this point, BoJack and Diane have gone their separate ways. They chat as old friends—in an incredibly poignant moment, Diane thanks BoJack for her time spent in Los Angeles, though she not-so-subtly implies that this will be the last time they speak.

The final scene of the series, with BoJack and Diane both sitting on the roof, unwilling to say goodbye, Season Six, Episode 16, “Nice While It Lasted.”

By the end of the show, they are two similar yet dissimilar characters, just like how they started. Diane’s growth has been positive in the extreme: she goes on antidepressants that help her immensely, she gets married to a kind bison from Chicago and she’s writing a middle-grade fiction series about a teenage mall detective. Finally, after seasons of being unable to figure it out, she’s happy.

BoJack’s downfall is also accompanied by growth, but for a moment in that rooftop scene, it seems like he’s dangerously close to slipping back into those old ways. “Life’s a b—h and then you die,” he proclaims to Diane, echoing his pre-rehab nihilism.

She counters him with a simple response: “Sometimes, life’s a b—h and then you keep living.”

BoJack Horseman doesn’t tell us the best way to handle problematic men, nor is it preaching about empathizing with abusers who use their power over others. It’s not about forgiveness, but it’s not not about forgiveness. It’s about understanding that the choices you make are yours to own. BoJack spends most of the series blaming others for his mistakes, one of the most frustrating and problematic behaviors he engages in.

By the end, all he can do is own up to the mistakes he’s made and keep living.

NO COMMENT