Intersex activist and DePaul alum Pidgeon Pagonis spoke about their global activism — and its origins at the DePaul Women’s and Gender Studies Department

Editor’s Note: This story discusses intersex genital mutilation and non-consensual surgical procedures.

The atmosphere at “A Taste of Their Own Medicine: Intersex People Fight Back,” was one of a warm reunion, rather than a serious talk. As the room slowly filled up, attendees were laughing and kissing each other on the cheek, embracing like long-lost friends.

Pidgeon Pagonis, intersex activist and co-founder of the Intersex Justice Project, was no exception to this; as their friends and former professors staked out seats at the front of the room, Pagonis would practically skip towards them, engulfing them in a hug.

Pagonis embraces Laila Farah, one the professors they cited as a mentor. (Sahi Padmanabhan, 14 East)

Beth Catlett, chair of the Women’s and Gender Studies (WGS) department at DePaul, summed the mood up perfectly.

“This is a homecoming,” Catlett said.

A Chicago native, Pagonis is now internationally renowned for their activism, but before they became a prominent advocate for intersex people, they cut their teeth in the WGS department at DePaul.

“I knew Pidge way back,” said Laila Farah, associate professor in WGS; Peace, Justice and Conflict Studies; and Critical Ethnic Studies. “Before Pidgeon was Pidgeon, just after they found out about the medical records at the hospital down the street, we spent many hours in my office going through it.”

Pagonis met Farah during their LSP 200 class. Farah also introduced them to the WGS program, which Pagonis says changed their entire college experience and beyond.

“This place changed my life,” Pagonis said. “This building is WGS for me. This is home for me.”

Even though they expressed joy at coming back to this place that felt like home, it was also full of conflict for Pagonis.

“This area is a place of conflict for me; when I walked in with [my assistant] I was joking that I was having PTSD or something else, I forgot what I said,” Pagonis said. “You know, school’s rough, and when I walked into this building, I felt it all come back… not only because of [school], but because this is where I found out I was intersex.”

Intersex people are are born with sex characteristics that don’t fit into the traditional boxes of male and female. Sometimes, these characteristics show up right at birth and are often labeled as birth defects. Other times, these characteristics don’t show up until puberty. Most commonly, people go their entire lives without realizing they are intersex unless they have a medical necessity to run tests that show those intersex traits.

When Pagonis was a baby, they were diagnosed with androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS). It affects people with XY chromosomes, in which their primary or secondary sex characteristics, such as gonads or genitalia, don’t line up with traditionally male or female categories. In many cases, this can lead to an enlarged clitoris, a partial closing of the outer vagina, undescended testes in the abdomen and, in complete cases, no uterus despite outwardly female-presenting genitals.

Pagonis first learned about AIS when they were sitting in a psychology class. When they found out that people with AIS couldn’t have children and didn’t have a period, something clicked.

“Those two things stuck out to me because growing up, my whole life, I knew I couldn’t have children, biologically, and I didn’t have a period, even though I was assigned female at birth,” Pagonis said. “But then it said these people have XY chromosomes, and I was like, that does not sound like me though, I went to an all-girls Catholic high school! I work at Abercrombie & Fitch! I play softball for an all-girls travelling softball team! I don’t have XY chromosomes, I’m a girl, I have a heterosexual boyfriend, I’m straight.”

Many people with AIS, including Pagonis, undergo surgeries throughout their childhood to make those primary or secondary characteristics line up as either male or female.

“I’m in Corcoran and I’m in the study hall and I locked myself in that room with cinder blocks, just like this, and I got my medical records for the first time,” Pagonis said. “And I read that I do have XY chromosomes. I read that I’m a male pseudohermaphrodite. I read that I was 1 year old and I had testes and the doctors removed them from my abdomen. I read that when I was four I had a clitorectomy, that my clitoris was too big for the doctor’s standards for a ‘normal girl’…and they took out my clitoris. I read that when I was 11, I had a vaginoplasty, without them telling me.”

Pagonis’ story is not uncommon among intersex people. The American Association of Pediatrics guidelines still recommend surgery as the main treatment option for intersex children. However, many of these surgeries are done when the child is too young to consent.

“These unnecessary surgeries are meant to normalize intersex children’s bodies without their input,” Pagonis said.

In Pagonis’ 2019 film, A Normal Girl, during an interview with their mother it is revealed that the doctors lied to their family in order to push them to consent to these surgeries on behalf of Pagonis. They told Pagonis’ parents that if not removed, the testes would become cancerous. They said that the cosmetic surgery to remove Pagonis’ enlarged clitoris would save Pagonis psychological harm in the future.

“My parents didn’t even know I was intersex because doctors like to use secrecy,” Pagonis said. “And shame. Because when you lie to people, and you keep things a secret and you keep them ashamed, you’re able to divide and conquer easier and not allow for community to form. So, they do that on purpose.”

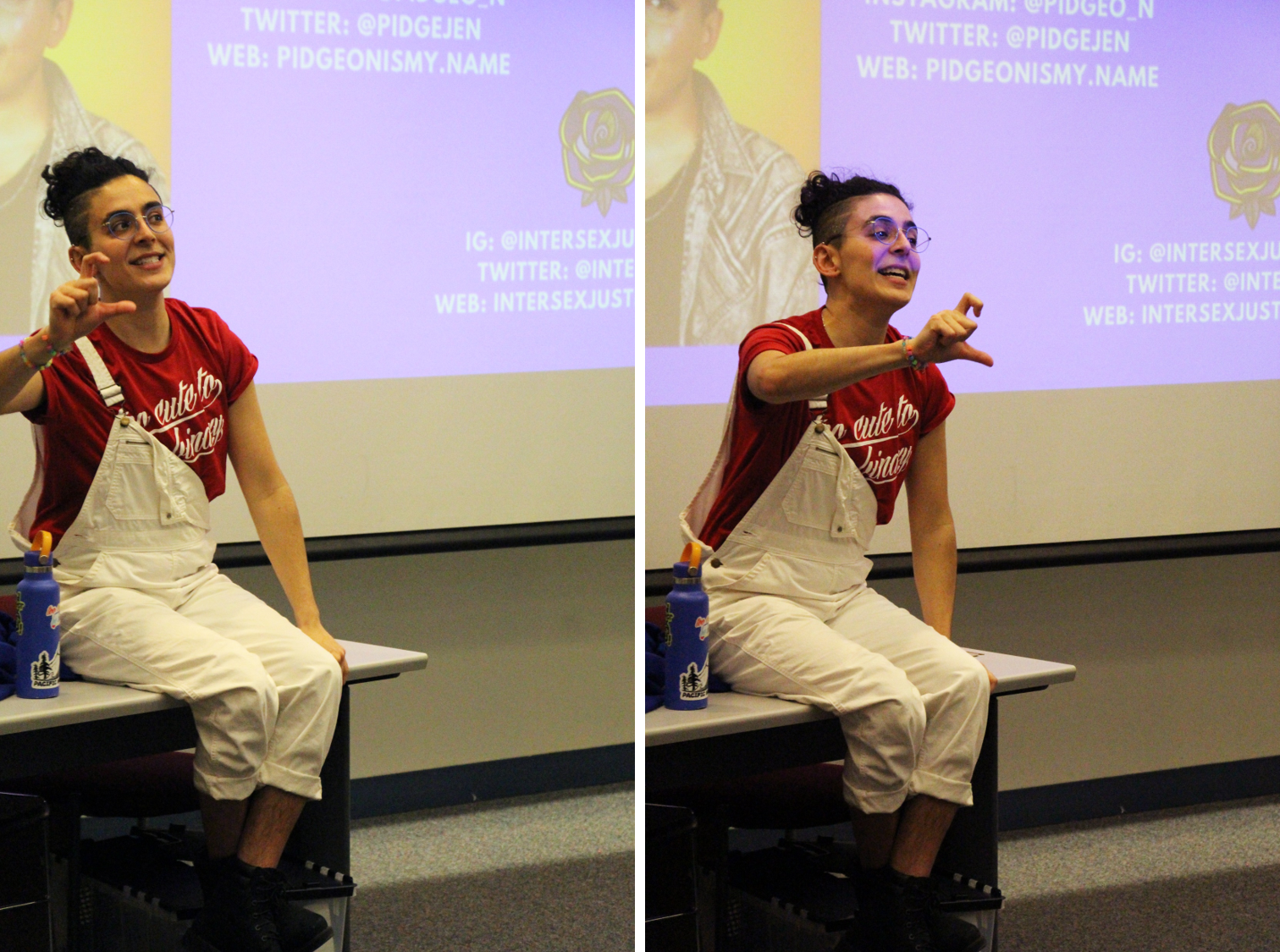

Pagonis is a dynamic speaker; they tend to talk with their hands, gesturing broadly and pointing their clicker back at the computer with flourishes. (Sahi Padmanabhan, 14 East)

These surgeries can lead to many side effects, both physical and psychological, that are detrimental to the child’s well being as an adult. In the ‘90s, intersex adults who had been among the first wave of intersex children to undergo these gender reassignment surgeries as children cited painful scarring, reduced sexual sensitivity, torn and nonfunctional genital tissue, lack of natural hormones and, in some cases, sterilization, as severe physical side effects that they were too young to understand or consent to when undergoing these surgeries.

“We all know about people who get bullied when they live outside of the box of gender norms,” Pagonis said. “We know people get bullied when their sexuality is outside of the norms of their culture. But this is a different manifestation of bullying. This is so institutional in the medical world. This is medical-industrial complex-level bullying with scalpels, and hormones, and lies and secrecy to prop up this fake bulls—t notion that there’s only men, and there’s only women.”

On top of this, intersex children who are socialized as a gender they may not feel comfortable with can be harmful for the child’s growth. A now-famous case of this is the story of David Reimer, who, in 1967, after receiving a botched circumcision at eight months old, underwent gender reassignment surgery.

On the advice of John Money, a psychologist at Johns Hopkins University at the time, Reimer underwent surgical, hormonal and psychological treatments to be “made into a girl” with disastrous results. Reimer was never able to overcome the psychological scars of being raised as a gender with which he did not identify, despite later changing his name and living as a man for the last few years of his life.

Pagonis themself suffered a deep depression after finding out they were intersex, saying that without the WGS department at DePaul, they don’t know what they would have done.

“I spent more time in your offices, crying, than I did in class sometimes,” Pagonis said, addressing their old professors at their talk. “And y’all held my hand and walked me through that horrible time in my life. And you did that for so many of us.”

In more recent years, the United Nations has spoken out against medical and surgical intervention on intersex children, calling it a human rights violation and torture on the level of female genital mutilation. However, in many countries, including the U.S., surgical intervention is still the norm.

The policy at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago is to treat intersex children, who are diagnosed with “differences of sex development” using a “multidisciplinary approach,” according to their website. This approach includes psychologists, endocrinologists, urologists, ethics consultants and social workers. Lurie Children’s did not respond to multiple requests by phone and email for comment on their policies concerning surgery on intersex children.

Pagonis has made it their work to raise awareness about the issues facing intersex people, especially children. Every year on October 26, Intersex Awareness Day, they protest outside of Lurie Children’s Hospital against medical intervention on intersex children. This is the same hospital where they underwent multiple surgeries as a child. They channeled much of their depression and hardship into this work.

“I think that one of the things about Pidgeon’s work, in terms of radical activism, which is one of their best gifts, is really their ability to handle really deep hardship with joy and to hold onto those two things,” Farah said.

Much of their activism comes in the form of talks given at schools and conferences across the world — just this past August, Pagonis was in Sydney, Australia, giving a talk about intersex issues at the Australian Medical Students Association’s Global Health Conference. Now, however, they want to step back.

“This is also an interesting year for me,” Pagonis said. “I’m going to probably transition out of doing this work in the next 12 months or so, that’s my goal. I’ve been doing this since I left [DePaul] 10 years ago and I really want to be home more and in my community more.”

For Pagonis, that community is not only Chicago and intersex people, but also DePaul.

“DePaul Women’s and Gender Studies has a specialness that I don’t think can be replicated,” Pagonis said. “And I don’t know if any other school has what we have in the WGS department here.”

Current WGS student Olivia Ruiz, who was at the talk on Monday, echoed this sentiment.

“Previously being a biology student and coming into the WGS program, which I do think of as a community, is definitely tight-knit,” Ruiz said. “There are certain kinds of communications and relationships here that you don’t get anywhere else.”

Pagonis attributes much of their activist spirit to DePaul, and they are grateful for the professors here who enabled them to pursue that activism.

“You guys really, not just the ideas and theories that you helped me learn in this school, which really helped me apply my life to a framework…but also [taught me] that I could learn stuff here and take that out into the world and hopefully create a change for intersex kids like me,” Pagonis said, addressing their former professors. “That really saved me, that saved my life.”

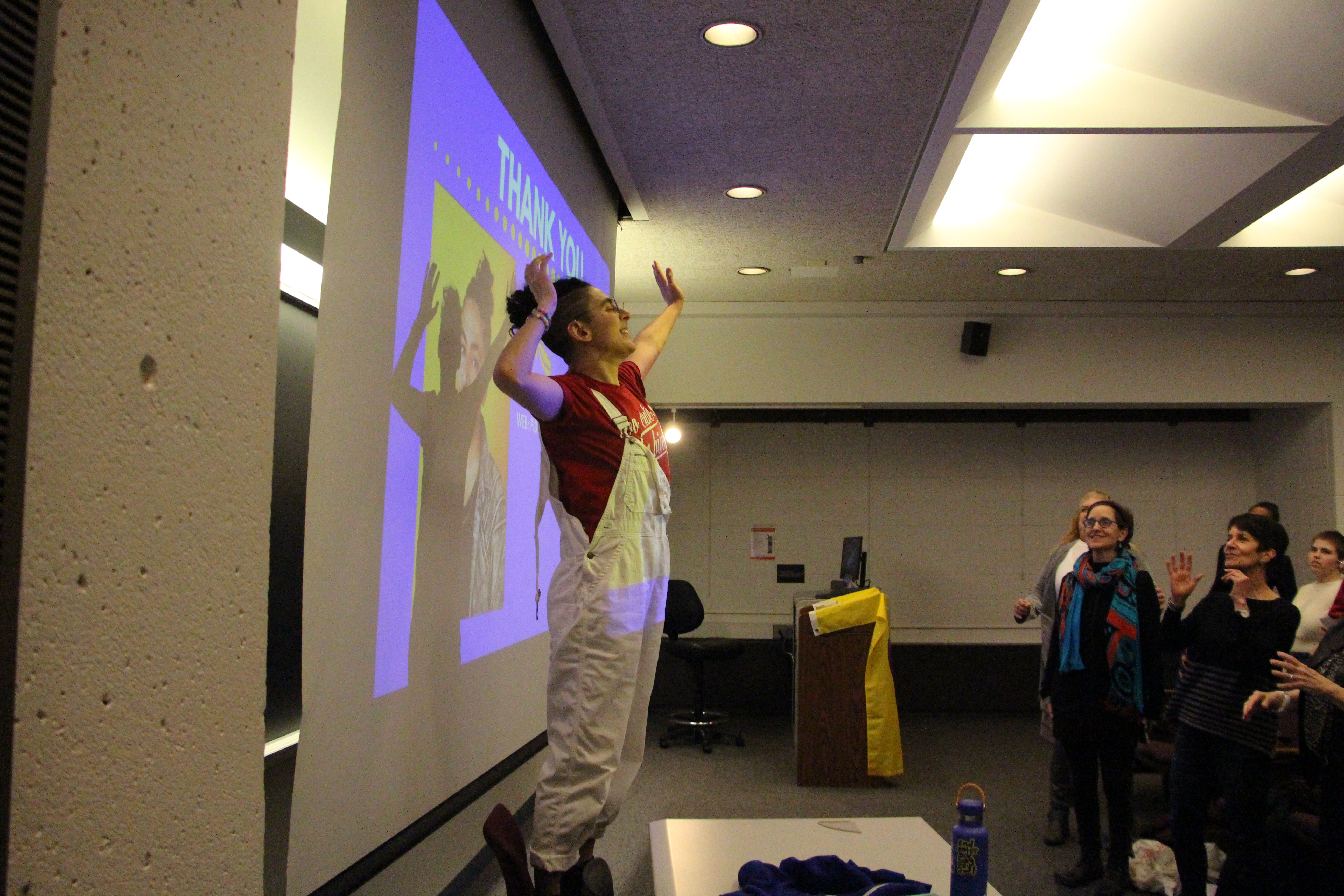

In a final moment of bringing the crowd together in the space that night, Pagonis had the audience stand up and led them in a chant—“No justice, no peace, no intersex surgeries. (Sahi Padmanabhan, 14 East)

Pagonis isn’t sure what the future holds, but they are hopeful.

“Next year, I hope to have a baby and raise that child and be in Chicago more and be with my cats,” Pagonis said. “I’m still always going to be, of course, connected to the intersex community and do things for my community, but it’s going to be in a different capacity and it’s going to be more artistic and it’s going to be more in-person and it’s going to be new and I don’t know what it is yet, but I’m excited for that.”

For more information and support around intersex issues and identity, contact InterACT Advocates for Intersex Youth or the Intersex Society of North America.

Header image by Sahi Padmanabhan

NO COMMENT