From picking cotton to migrating North, Oralia Barrera, 88, reflects on her life as a Chicana woman in the 20th century

It was 1932 in the small town of Karnes City, Texas, 54 miles east of San Antonio, where my great grandmother, Oralia Barrera, was born into a life destined for many Chicanos and farmworkers in the South during the Great Depression — a life not often highlighted in high school history classes: cotton-picking.

I can remember what my 12 years of public school history taught me about the white experience in every occurrence and, vaguely, the African American experience, too. Yet, when it came to the whole “Southern notion of living” during times like the Great Depression or the Great Migration and sharecropping era, not once did I assume my Mexican heritage was also a part of that history.

Oralia’s father, Antonio Barrera, a lifelong sharecropper born August 6, 1901, in Floresville, Texas, was a hard worker who worked under the often crippling sun. When Antonio and his family made the move to Karnes City, Texas, they participated in the system of sharecropping. To Oralia’s recollection, he paid a white landowner a fixed fee so that once it was paid to the landowner, he could pick and use the cotton from the landowner’s land however he liked. In this case, he strived to pick the most cotton and sell it to outside companies who were looking for a cheap price for the commodity wherever they could find it. To achieve this, her father moved Oralia and the rest of the family up to Lula, Mississippi, where they would continue the same work with the same sharecropping methods and would work countless hours picking cotton with no wages in order to profit off his cheap offers.

Oralia herself was still in her adolescence and had not yet even learned to write. In fact, writing was so trivial compared to work, Antonio decided to take her out of school altogether after she completed the first grade.

She could remember vividly that had other sharecroppers picked more cotton at the end of the workday, the price to pay was a beating from her father with what she described as the hard and rough stem of some sort of plant she couldn’t remember the name of.

With a pondering look, Oralia recalled the range of people she worked alongside — mainly Mexican and African American people. She even recalled the fights that they would have with each other when they’d pick more cotton than the other, emphasizing the constant hostility between the different racial and ethnic groups. According to Oralia, her family was hostile towards African Americans due to the competition of who could pick the most cotton.

She had trouble remembering how she felt when she picked cotton, but surprisingly the topic did not sadden her like I thought it would. It seemed to me that she liked the idea of helping her father out, despite the grueling conditions. I could even see her rub her fingers together as if she had been reminiscing a vivid moment with cotton in between her fingers. Perhaps her rubbing her fingers together all the time unknowingly was more than just a habit.

From 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., she worked the fields with her siblings — they were the only children she could remember on the fields. At noon, she’d make lunch for the whole family. She told me it was the sun that told her when it was time to work, eat, and go home. When I asked her what she ate she replied with the classics: beans, rice, tortillas de harina y huevos rancheros. According to Oralia, having food on the table was enough stability for her family.

“They nicknamed me La Chiva,” she told me, a cheeky smile plastered on her face. This was because she enjoyed climbing trees on the land as a kid, much like a goat would. Yet, apart from those trees, and the racial divide, there were many other obstacles she’d have to climb in Lula. Like the loss of her 14-year-old sister, Dora, who while fulfilling her domestic duties tragically got sick from contaminated water and died on December 14, 1943.

“We were going to wash at the tank between the mountains. Dora didn’t know that the water was hot at the bottom and cold at the top,” said Oralia. “She didn’t know she had her period and she went into the hot water. My dad took her burned body to the hospital where she died because she developed tuberculosis.”

She couldn’t sum up her feelings or anyone else’s much at the time, but she knew Dora’s death wasn’t taken easily. She could, however, remember the vulnerable state she saw her sister in. “She wouldn’t eat,” Oralia said. “She was always coughing.”

Dora was in the hospital for a week before she succumbed to tuberculosis.

Not long after, her mother, Rita Garza, who was born April 10, 1905, died of the same condition on November 24, 1948.

Nonetheless, life went on for Oralia and the rest of the Barrera family. It had to. A part of moving on, for Oralia, included getting married at 19 to a man named Pancho Rincon who she met while picking cotton in Lula. It wasn’t long after that when her father remarried and settled down with his new wife in Lula as well. Not only was he sharecropping with Pancho, Oralia and her children, but he was also a watchdog who guarded the town with a gun in hand every day.

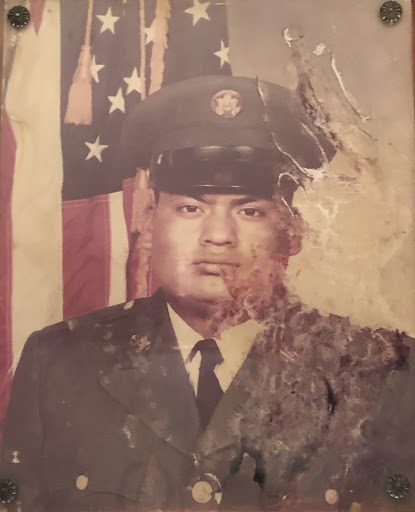

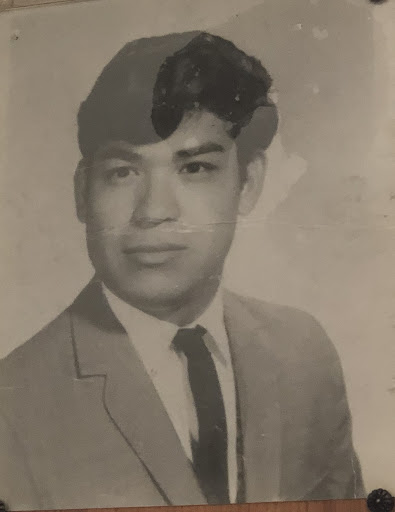

Life remained this way for a decade until Pancho left Oralia and she had to raise their six children alone. With no husband or job to sustain her, Oralia made the tough decision to move to Chicago and leave her children with her father and his wife. Oralia’s sons, Albert Rincon, 19, and Danny Rincon, 17, decided to enlist in the military as they saw this as their best career option to be successful in the United States. They served in the military for about 20 years.

Because her daughters were left with Antonio, they, too, picked up the family trade of picking cotton. “I don’t remember much, but all I knew was that I hated picking cotton,” said Irma Rincon, one of Oralia’s daughters. “I was young. I wanted to play.” This was a sentiment she assumes her siblings felt, too.

Irma knew, however, that Oralia made the right decision to move up North. “I was very young, I knew my mother couldn’t support us, couldn’t feed us. She had no money so she left us with our grandfather. She went to Chicago for work,” Irma said.

Like many Latinx and African Americans, Oralia found her way to Chicago during the Great Migration in 1962.

From South Chicago to Bridgeport to Back of the Yards, Oralia called many places her home and many factories her job, including Wisconsin Steel. She worked mainly in steel operations but also had experience as a bartender and as a caregiver.

Yet, one of her most notable priorities was her granddaughter that she raised since she was a mere few days old — my mother, Oralia Ramirez.

As I sat next to my great grandmother in my old bedroom where she now resides in the care of my family, there is nothing she loves more than her children, grandchildren and a really good, romantic novela. Of course, her story is far more complex than any writing could ever capture and, surely, it’s not as innocent a tale I might want to think of my ancestors. But I think Chicano history is not perfect nor is it often as spoken about as it should be.

Chicano history is not very prevalent in the common core curriculum of public high school education and I’m often left reminding myself it is not my fault that I cannot accurately understand my grandmother’s or many other Chicano experiences. Nor can I accurately create a vivid depiction of where she worked, how much she was paid, or how society treated her because I was never taught these stories in my history textbooks

Oralia Barrera is just one Chicana woman who lived to tell only a fraction of the intricate tale of her childhood and adulthood to her great-granddaughter. To some, maybe it isn’t so interesting, but to the lives of millions of Chicanos and Latinx in America today, it is our story. It’s important, then, that we all try to seek these stories from our ancestors and tell them to future generations so they won’t be forgotten.

Header image by Natalie Wade, 14 East

NO COMMENT