How student activism and appetite slowly built an ethnic studies program

Students at Northwestern were hungry. They put nothing in their bodies except V8 juice and huddled in tents in front of The Rock, a frequently spray-painted landmark central to campus and its activist causes, to avoid pacing outside in the early April wind and snow not unlike this spring. They waited for the school administration to take action, or at least commit to a timeline for their cause: developing an Asian American studies program.

The students felt like the university was failing to serve a substantial part of the population by not offering any academic outlets to learn about the Asian American experience and the country’s history of anti-Asian sentiment. When four years passed since students started campaigning with no serious commitments from university administration, student activists organized a strike in the spring of 1995 to demonstrate that their hunger for the program was greater than their bodily needs. Over 100 students participated over 23 days, and the protest garnered attention and support from other universities. But change was slow to bloom.

Twenty-five years later, the student protesters are now professionals out in the world.

The hunger strike originated with Robert Yap, a senior who wanted to escalate pressure on the administration and show the passion of the students.

Yap and other Asian American students at Northwestern were frustrated that they did not have an academic avenue to learn about their own histories and backgrounds, so they formed the Asian American Advisory Board, or AAAB, in 1991 to advocate and organize. Some of the students knew each other previously, but most members organically heard about the board. Their goal was to provide the school with student input and make program and faculty recommendations to get an Asian American advisor on campus.

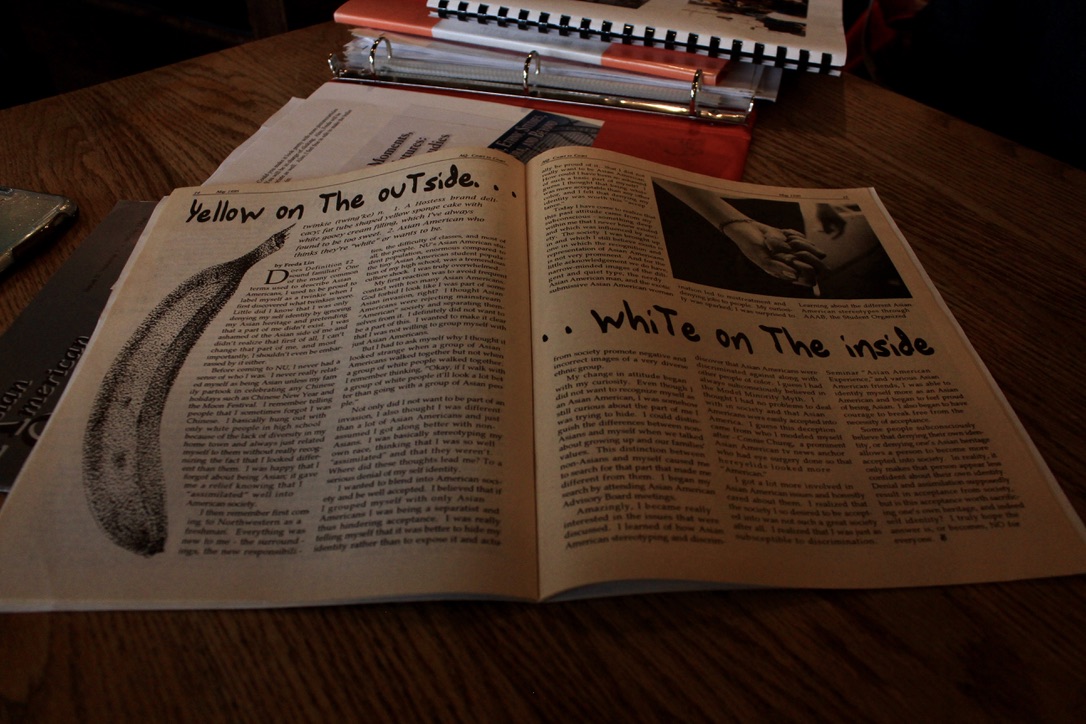

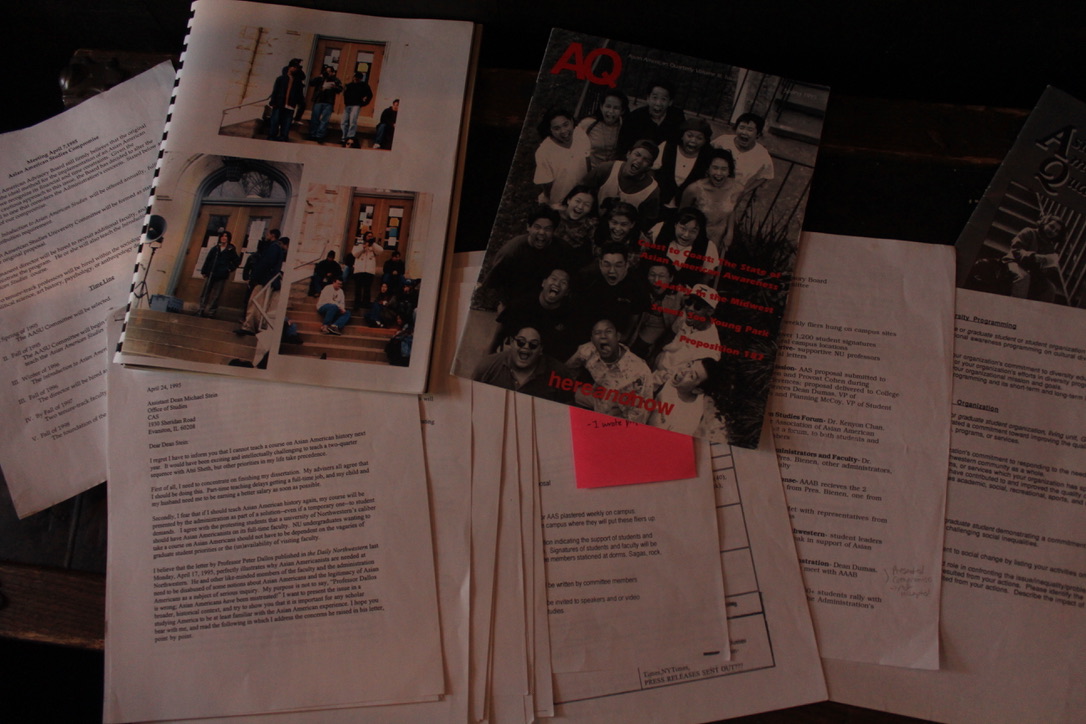

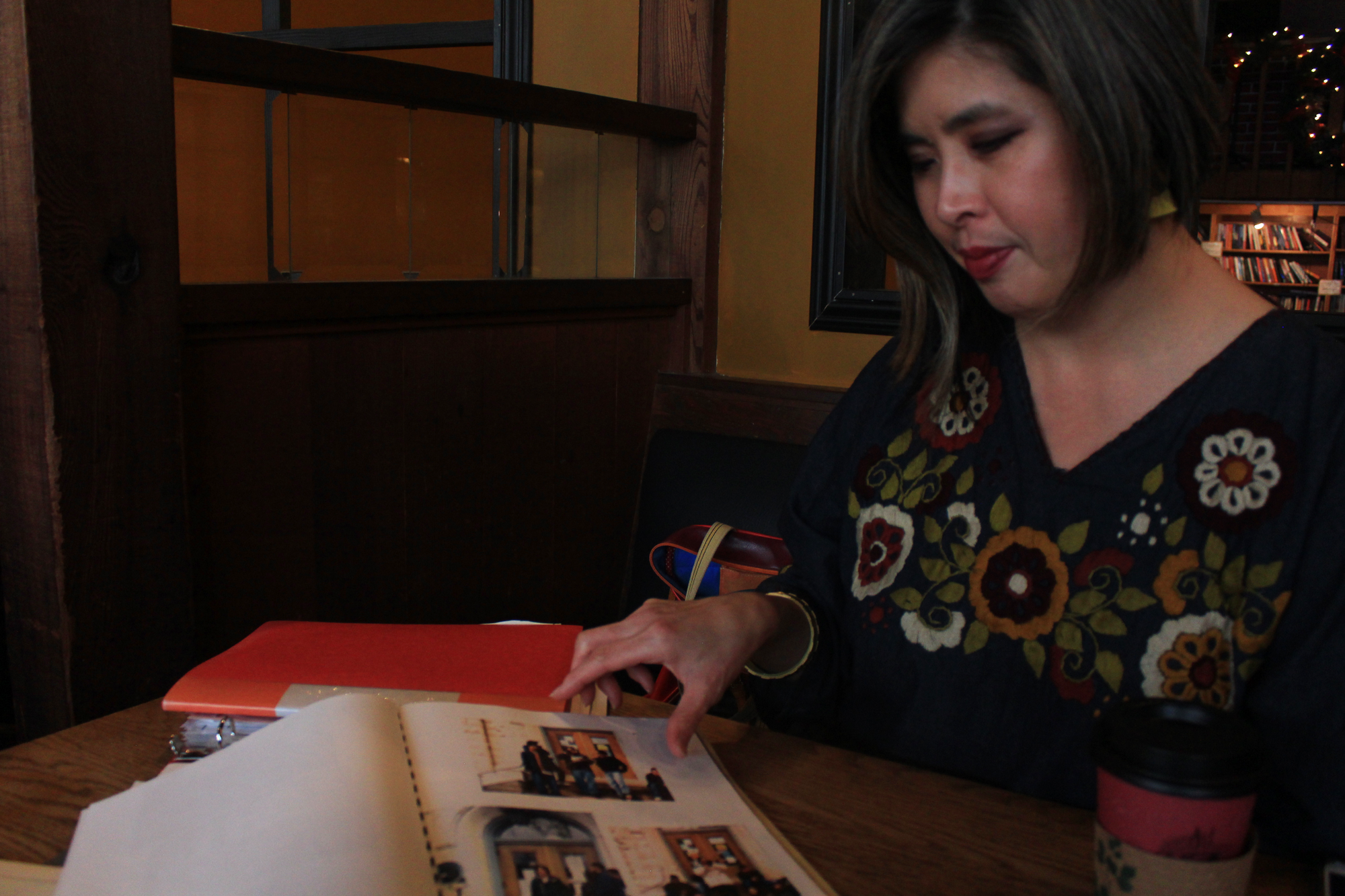

Freda Lin joined AAAB in her sophomore year when she applied to be the editor for the organization’s magazine, the Asian American Quarterly. She brought preserved copies of the Quarterly to show me, among other records from her time of college activism. When Lin arrived on campus as a freshman in 1991, she was stunned at the number of Asian American students and the diversity of their communities.

“It’s really quite unbelievable how I was in that space for much of freshman year of just trying to continue the way I was in high school of blending in,” Lin said.

She thought of herself as fully assimilated in her home area of New York (she wrote about being a “Twinkie” in the Quarterly) and was initially worried about seeming too Asian by hanging out with her native Chicagoan roommate’s Asian friend group. Still, her innate curiosity about Asian American history pushed her to get involved in student groups. When attending a conference with classmates at the end of her junior year, she stumbled upon the Asian American Studies Conference being held at the same time, which opened her eyes to the academic field.

“I saw all of these people, professors, undergrads, graduates speaking so eloquently and passionately about an academic field that, you know, was completely absent at Northwestern,” Lin said. “Then just realizing like, we need to do this so that other people won’t grow up at a homogenous community not knowing about themselves or even non-Asians knowing about Asian American experience.”

In 1991, the student advisory board submitted their first recommendation for an Asian American advisor to the Office of Student Affairs, claiming the advisor could act as an advocate and help develop a full program. It was rejected. A year later, AAAB submitted a revised proposal. It was rejected. They tried again in 1993 and were once again rejected. Lin, inspired by her exposure to Asian American studies, helped bring the president of the Association for Asian American Studies to Evanston to speak at a forum in early 1995. By the time of the spring 1995 protest, they surveyed the student body and submitted a 200-page proposal for an Asian American studies program complete with faculty letters of support, successful proposals from other universities and more than 1,200 student signatures – yet it faced the same fate.

Before the weather started to turn warm, another change hit Northwestern. Henry Bienen, formerly the Dean of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University, assumed the role of university president in January after being elected in mid-1994. Bienen, who had lived abroad conducting research in Africa and Japan and went to graduate school at the University of Chicago, said his marching orders from the hiring committee were to elevate Northwestern to the status of other top-tier private universities by establishing research structures and internationalizing the student body.

“You’re opportunistic, you can’t do everything. You try to do one thing here, you do it, another thing it’s like batting your head against the wall,” Bienen reflected recently. “You can’t do it, so you go on to something else.”

Before the start of the strike, AAAB held a press conference on April 10. Yap said that the administration had only been willing to commit to the idea of pursuing a program, which they received word from in letters and in meetings with administration. “But they’ve been saying it for two years. They’re still stuck in bureaucratic garbage,” he told the Daily Northwestern in the April 10, 1995, issue.

“Like every department or program, you have to have at least some structure to trying to vet what you’re going to do, how much it’s going to cost, what your faculty resources are, what student demand really is,” Bienen said recently. “And that’s not for the president to say, that’s what curricular committees are for.”

On April 10, Bienen stated that the students’ efforts would not be effective in swaying administration. He was deeply familiar with student protest since being involved in the Movement for New Congress, an attempt to get students against the Vietnam War elected as U.S. representatives. He was nonplussed.

“I think it is a very inappropriate response. It’s not the way to go around changing things in the curriculum,” Bienen was quoted in The Daily Northwestern’s April 11 issue. “This is not a bargaining process.”

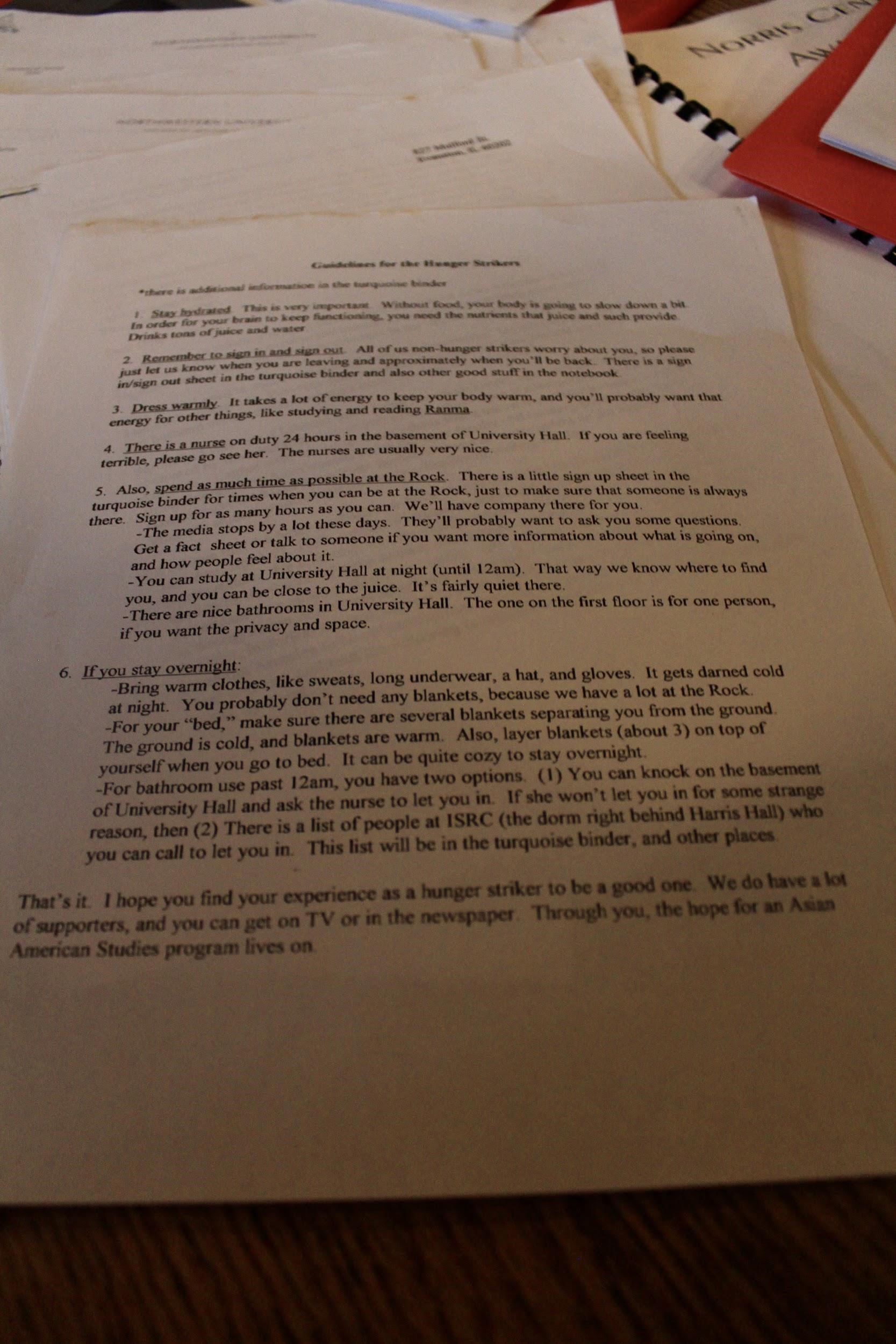

That Wednesday, April 12, AAAB held a rally and chanted “no program, no peace” outside of Bienen’s office, though he was not there. The crowd, approximately 200 people, was also made up of non-AAAB members and students from other organizations: the Bisexual, Gay and Lesbian Student Alliance (BGALA), Casa Hispana, the Black Greek Council and more. Then, 17 students started fasting in tents by The Rock as a public hunger strike, and 60 others registered to do one-day fasts of solidarity. The school stationed a 24-hour nurse to deal with potential health failings, and Lawrence Dumas, the Dean of the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, wrote a letter to AAAB promising to bring relevant academics to campus.

Bienen said nearly the same thing now that he did at the time. “That’s not how we respond to demands. But, you know, we certainly don’t want anyone to become ill.”

Sumun Pendakur, now the chief learning officer at the University of Southern California Race and Equity Center, was a freshman when she spotted an info table on campus near The Rock.

“I vividly remember walking by the table and Rob Yap called me over,” she said, remembering the Asian American Heritage Month t-shirts laid out on the table with the theme “coloring outside the lines.” “Like all good college students, I needed my fair share of free t-shirts.”

Yap told her about the strike, which was on its second or third day. She was appalled at the administration and inspired by the students. She was already involved in the Indian Student Association, which allowed her to dance in cultural shows and find other students who loved Indian film, but AAAB’s mission registered to her as an important political cause. She signed up for a three-day solidarity strike.

“It’s so narrow what we’re taught about ourselves, and when I say ourselves, I mean broadly about Asian Americans, but also for all people in this country,” Pendakur tells me now.

By Northwestern’s current metrics, 23 percent of the class of 2023 identifies as Asian American. The university’s Asian American demographic has hovered between 17 and 25 percent of the total population for decades. International students make up 11 percent of the student body. Ethnic studies programs can serve as an outlet for diverse representation, but function like other lines of academic inquiry that intersect history and identity, such as language studies or sociology.

“Asian American studies, like any form of ethnic studies, gender studies, queer studies, sexuality studies, is not just for the community that it studies, but rather for the entire community to better understand the landscape of really how power functions,” Pendakur said. “Power, knowledge, history, resources, everything.”

Ethnic studies programs became popularized in U.S. universities in the late 1960s as one division of the Civil Rights Movement. Over 50 years ago, the Third World Liberation Front protests erupted at West Coast universities to fight for ethnic studies programs that diverse students could see themselves in: African American studies, Latino studies and Asian American studies. They were tired of not having an academic avenue to learn about their own histories and backgrounds. The 1968 San Francisco State protest and University of California-Berkeley protest that extended into 1969, both months long, are some of the longest demonstrations on college campuses in U.S. history.

Students at Northwestern weren’t backing down, even in the face of resistance, which came to a head the second day of the strike, April 13.

“We were at The Rock and a fraternity showed up,” Pendakur said. “I don’t remember which fraternity, but it was a white, mainstream fraternity, and they showed up with pizza and proceeded to eat it in front of the hunger strike there.”

The fraternity she was remembering was the Conservative Council, a right-wing political group.

“We were demonstrating against the absurd by being absurd,” the group’s president, Kevin Frost, said to the Daily Northwestern at the time. “It’s like lying in the office and kicking and screaming because you didn’t get your way.”

Lin, though not hunger striking because she was planning AAAB’s next steps and finishing her senior year, was in the tents visiting the protesters when the pizza incident happened.

“I was really just disgusted that people would, you know, taunt students for wanting to stand up for something that’s important on campus,” Lin said. “It’s just very childish.”

Another facet of ethnic studies programs in college is that they cover gaps in worldview often left unfilled in traditional pre-college education.

Pendakur grew up in Evanston. Her dad was a member of the radio, television and film department at Northwestern. A self-described “campus brat,” she remembers seeing the landmark documentary Who Killed Vincent Chin? as a kid when it was screened at the university in the 1980s. The film follows the trial proceedings after two auto workers in Metro Detroit antagonized the 27-year-old Chin, out at a strip club for his bachelor party, and mistaking him as Japanese, beat him to death on a summer night in 1982.

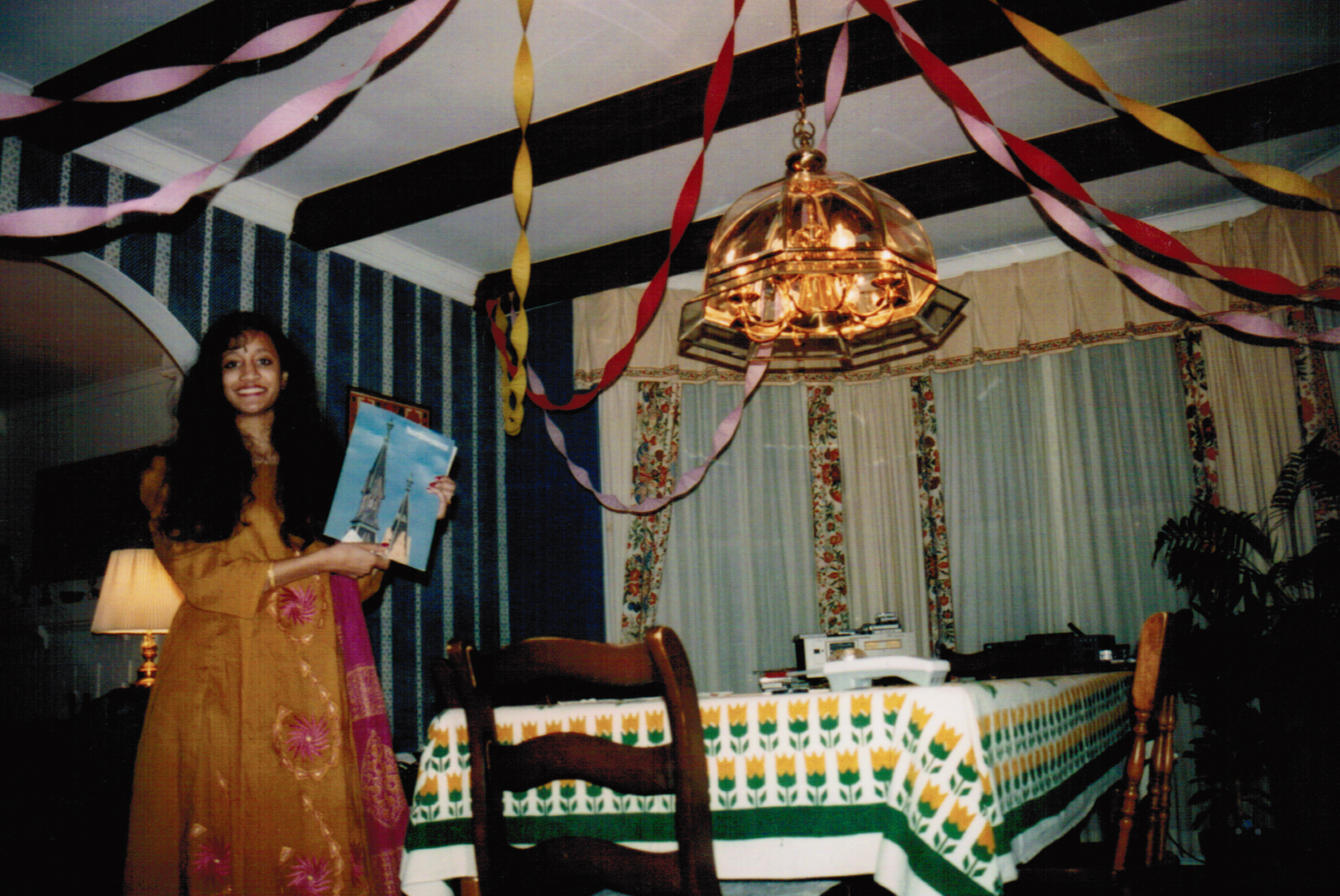

Sumun Pendakur in winter 1993 after receiving her acceptance letter from Northwestern. Photo courtesy of Pendakur.

Despite this experience, Pendakur still felt uneducated on Asian American history and unfamiliar with narratives outside of her own Indian American experience, having been one of only about 30 Asian kids at Evanston Township High School. That’s why she found the idea of an ethnic studies program refreshing and exciting. Others did too, she said.

“People were hungry, hungry for the education that had been kept from us through our k-12 educations,” Pendakur said. “If you think back to your own kindergarten to 12th grade, you could probably name how much you learned about Asian Americans and Asians in that period.”

She said that most people remember learning about the Chinese immigrants working on the railroads, some remember learning about Japanese American internment (or imprisonment) during World War II, and a rare few might be able to recall one other factoid from their formative education years. There was clearly an opening and a need to learn more, she thought.

The protesters kept striking in part because they felt that they already had proven student interest. They frequently fliered the campus, circulated petitions and used phone trees to drum up support. As part of AAAB’s initiatives to show that a program would be welcome, they self-taught teach-ins on Asian American studies topics. Students from different disciplines taught full classes on top of their normal workload, but were repaid with passionate student engagement.

“I’d say every one of these classes — I remember taking one on Asian American feminism, again taught by a grad student — full. Forty students in that,” Pendakur said. “There was another class on South Asian Americans in the United States — full. Thirty-five students in that.”

During the strike, students used this appetite for knowledge to motivate them to persist in the face of mental and physical struggles. Lin later participated in a two-day fast in solidarity, and even then struggled to focus.

“I was just like, okay, when is this going to be over, I’m like really hungry,” Lin said. “I was obviously like, I need to do this, I need to take a stand and be in support of the people who are sacrificing themselves, especially the people who are sleeping outside.”

Grace Lou, who had just taken over as AAAB chairperson in spring elections, also did a three-day solidarity fast, but was worried about the strikers in the tents.

“It was really selfless — it was hard academically,” she said of the strikers.

AAAB’s guidelines for behaving during the strike. Meredith Melland, 14 East.

The strikers continued to hold out hope, even when other Asian American students on campus said they didn’t understand what they were doing.

“But when one side attempts to force another side into moving too quickly, a chasm is formed. The hunger strike started this chasm,” wrote students Jason Liu, Geoffrey Gass and Fei Yeh in a letter to the editor in the April 17 issue of the Daily. “We need to stop this right now, return to the table and start talking again before the situation is blown even further out of proportion.”

Other students and faculty used the newspaper’s platform to voice opinions on the controversy. Emotions ranged from enthusiasm for the student body’s newfound activist energy to frustration at the “special treatment” opposers expected Asian Americans to get. In the paper’s April 19 edition, Peter Dallos, a professor of neuroscience and audiology, wrote in opposition to the proposed program because Asian Americans were not a homogenous group, did not have an immigrant experience significantly different from other ethnic groups and represented less than two percent of U.S. demographics.

The students held a second rally on Monday, April 17, chanting to a traditional Korean percussive beat with students from the University of Illinois at Chicago and University of Chicago, though plenty of the faculty and student body had not yet returned to campus after Easter and Passover. At this point, seven students had to drop out of the continuous strike because of health or academic concerns.

President Bienen wrote another letter that day advising students to stop. Two days later, Dean Dumas met with students to negotiate and students on the East Coast at Columbia University began forming a committee inspired by AAAB. Soon, students from Princeton — the university where Bienen spent most of his pre-Northwestern career — would follow suit.

Dumas tried to compromise with students by offering funding for four courses for the 1995 and 1996 school years. On April 20, AAAB students rejected the offer in a letter because there was no “guarantee that NU students will always have the opportunity to take a course on Asian Americans.” Some observers viewed this a shrewd move, others thought it caused them to lose gains with the administration.

AAAB led another rally on April 23, disrupting potential new students on a visiting students day. They garnered the support of the Midwest Asian American Student Union, which held a 24-hour solidarity protest at schools including Ball State, Indiana University, Pennsylvania State and University of Maryland. DePaul, UCLA, UIC, Brown, Columbia, Cornell, University of Maryland, Princeton and Stanford sent messages of support to the advisory board.

After 20 days and little movement from the administration, the students began to lose steam. One of the student protesters, Charles Chun, didn’t eat for 13 days. As the longest continual striker, he lost between 15 and 20 pounds, according to an April 24, 1995, story by Chicago Tribune reporter Melita Marie Garza, who covered the strike’s arc.

When movement leaders met with Bienen on May 2, he told them he would commit to nothing further than the four-class proposal. On May 4, the protesters ended the strike and prepared to remove their tents from the campus.

“The strike was not affecting the administration the way it did in the beginning,” Grace Lou told the press.

Surrounded by distinguished administrators and faculty clad in dark robes, Bienen was formally inaugurated as president on May 5, 1995, while 30 students with all-black outfits and yellow ribbons stood silently in protest.

The AAAB members and protesters were resigned to accepting the administration’s proposal to create four classes by the next fall, feeling like it would be better to lobby faculty directly.

“A lot of folks talk about the movement of Asian American studies at Northwestern as only focused on the strike, and it was a really important and pivotal moment, but not necessarily in the way that folks think,” Pendakur said. “It was long, it brought national and international attention, and yet at the same time, it didn’t actually result in major gains because the institution kind of continued to ignore Asian American studies.”

Over the phone, Pendakur gets quiet when I ask her why the administration took so long to inch forward.

“I think the administration was hoping that students would just graduate and that next year, students would not have the succession planning and capacity building we engaged in, and would just, we would just die, right?” She said. “And that they wouldn’t have to deal with it, they wouldn’t have to allocate money and resources and save and funding and budget for any of it.”

Pendakur noted that the university had already invested long ago in an ethnic studies program — the Africana or African American Studies department.

Northwestern’s African American Studies department, founded in 1972, is also the result of student protest. Black students led a sit-in in the college’s business office in May 1968, prompting the administration to commit to increase the school’s curricula on Black history and literature. Lerone Bennett, senior editor at Ebony magazine and historian, and C.L.R. James, an anti-colonial activist and Marxist theorist, were two of the department’s first hires. After 48 years, the department is now operating with over 16 faculty members and additional grad students and affiliated faculty. Maybe, Pendakur said, the school thought that was enough.

“There are a whole host of historical, sociological, political, economic issues around or inside Asian American studies: demography, income stratification, patterns of migration. Every one of those things are interesting to study and think about,” Bienen said now. “I’ve never thought somehow or other that this was not a proper area of study. The trick was to do it in a way that, you know, fit inside the university’s academic interests.”

Lou, Pendakur and other activists persisted into the new school year. AAAB hosted the 1996 Midwest Asian American Students Union (MAASU) conference and leveraged the extra students to march up and down Sheridan Road in protest of the slow administration movement.

When Dean Dumas retired from his position, the organizers reached a turning point; Eric Sunquist, an academic coming from the university with the oldest Asian American studies program in the country, UCLA, became the new head of the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences.

“He was such a wonderful ally, and with his partnership, we actually moved the needle much more quickly than had occured in the prior couple of years,” Pendakur said.

Through continued letter-writing and petitions, remaining student activists met more with upper administration until a search for a program director commenced in 1998.

In 1999, after four years of student proposals, hunger striking, organizing and lobbying, Northwestern University created an Asian American studies minor program.

The university hired Ji-Yeon Yuh — a former journalist who returned to academia to study history and the Asian diaspora at the University of Pennsylvania as a graduate student — to teach classes and run the program.

“And a lot of that meant working with students to build more awareness about Asian American issues, promote the classes, create more classes, so you know, these were all classes that I was creating for the first time, so it was a lot of work,” Yuh told me.

In addition to classes, she also worked with students to plan programming and events. Even though most of the original strikers had graduated, she still felt student interest was substantial.

“The student organizations that had pushed the hunger strike were still there, they had new members, they were interested in the program, you know, they took classes, they came to events, so they worked hard, too.”

She conducted three faculty searches, usually a two-year process, and hired three core faculty members in five years while getting students on track for the minor program.

“To Northwestern’s credit, they did provide, I wouldn’t say sufficient, but they provided resources that allowed us to establish and grow a program,” Yuh said.

More Asian American Advisory Board records from Freda Lin. Meredith Melland, 14 East.

Vishal Vaid, a current IT manager who started at Northwestern in 1997, was so interested in learning more of his background that he started distributing petitions to garner student support for Asian American studies and Hindi language programs independently, not knowing about older activist movements on campus.

“You get on campus and you’re excited to sort of discover yourself and you realize that there’s just not the requisite vehicles to give you that awareness and to give you sort of that underpinning that you need to sort of become whole, it gets you a little annoyed,” Vaid said.

Vaid managed to take Hindi classes when an engineering professor agreed to teach the language and was one of two original students to graduate with the Asian American studies minor in 2001.

“It was very gratifying because, I mean, we had spent hundreds of hours trying to get this, trying to get this done, not just in the coursework itself, but also in the fight that led up to it,” he said.

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the program went through a stagnant period where student interest plateaued and the program couldn’t hire any new faculty members, but Yuh said it focused on establishing its presence campus-wide. Still, it remained a minor program.

“There are a lot of universities that have programs but don’t have degree-granting departments in the area of the program, that’s not at all unusual, whether it’s area-focused Russian studies or Latin American studies,” Bienen said.

Bienen said this usually has to do with a combination of student demand and the hiring capacity of the university.

“From their perspective, they want to be sure that students will come, right? That they will take our classes and become majors and minors. They want to see proof of that, I think, before adding more faculty,” Yuh said.

Both Yuh and Bienen pointed out that as a growing academic field, it took time for people to graduate from Asian American studies programs, conduct research and take up teaching positions.

“But from our perspective, there’s a limit to how many courses we can offer because of the number of faculty that we have, and so, we’re never going to see tons of students unless we have more faculty,” Yuh said. “Right now, we’re teaching pretty much at capacity. Our courses are full. A number of our courses consistently from year after year have long waiting lists, so there is demand and it’s pretty clear to us, anyway.”

In 2016, the Asian American studies program became degree-granting after the major was proposed by core faculty in 2015, the 20th anniversary year of the hunger strike. Hailed by administrators, faculty and press as a victory in the long fight, the new major program garnered only slightly more staff and resourcing. The program’s current director, Nitasha Sharma, described its precarity as a program compared to a department.

“We have less power, we have less funding, the directors do not get the same compensation as chairs of departments, even of small departments. We don’t get to vote on the people that we hire,” Sharma said. “That’s really shocking, we don’t get to hire them really, on our own, and we also don’t get to vote on our tenure and promotion.”

Until recently, five core faculty taught in the program, four of whom had tenure and one who was teaching track. However, their tenure is based out of different “home” departments, meaning they have to split their time between two divisions. Even Ji-Yeon Yuh, once Asian American studies’s only faculty member, is tenured in the History department and splits her class load between the two. There was no option for tenure in Asian American studies because it is not a full department.

Pranav Baskar, currently a journalism student at Northwestern, reported on this dual obligation of ethnic studies faculty outside of the African American Studies department for the Daily Northwestern last May.

His story, “Doing Double: Ethnic studies programs — suffering funding and faculty dearth, high turnover rates, intense working conditions — demand structure reform,” examined the requirements and frustrations of professors in the Asian American studies program and the Latina and Latino studies program, created even later.

“All four tenure-track professors in Asian American studies have 50 percent appointment within Asian American studies and 50 percent in a tenure home,” Sharma, who is tenured in African American studies, told Baskar. “What that means is that every single person hired in the ethnic studies — we have [to] do twice the service, twice the labor, twice the meetings, twice the students compared to anybody who is a 100 percent hire in English or a 100 percent hire in history, for example.”

The program initiated ten new searches for professors in the past five years — all hires who have since left the university, according to Baskar, possibly because they could not be tenured in the field. The high turnover makes it difficult for the program faculty to keep up with student interest in program-specific classes, which frequently fill up. However, years of student activism and faculty work have generated recent movement for Asian American studies.

Weinberg Dean Adrian Randolph applied for and received a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon foundation to create an Intercultural American Studies Council, which granted the program boosted funding. Starting in fall 2019, the program conducted a search for a new hire all its own.

“For the first time ever, we’re doing a search to hire a professor of Asian American studies. We’ve never been able to do that. That means it’s a 100 percent hire in our field, we don’t have to pair with a department, and nobody had to leave or retire or die for us to get this line,” Sharma said.

After fielding applications from over 100 applicants for the tenure spot and conducting four in-person interviews with candidates — all of whom Yuh described as exceptional — Northwestern hired Patricia Nguyen, the program’s teaching track professor, as the first Asian American studies tenure track professor.

In terms of growth, Yuh sees Northwestern’s program as middle-of-the-pack. She told me that in the same time it took Northwestern’s program to offer degrees, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign instituted a program out of student demands in 1997, departmentalized in 2012 and now offers a major with eight to 10 principal faculty members. University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) had an equally if not more tumultuous path as Northwestern to a minor program, created in 2009, but later combined Asian studies and Asian American studies into a Global Asian studies program in 2016. Like DePaul’s Global Asian studies program, the UIC GLAS program bases its origin in the idea that in a time of instantaneous transnational communication, migration and history can no longer be segmented by area.

Despite the Northwestern program’s long history of protest, like other Chicago schools, not everyone on campus knows the background now.

“I did not even know that was a thing,” Baskar responded when I said I wanted to research the program because of the hunger strike. “This just speaks to how much people have had to fight to have just their histories valued equally as the other histories we put a premium on, typically white ones, typically Western ones, typically European groups.”

But it is a part of Chicago history, Vishal Vaid told me. His son, a fifth grader in Chicago Public Schools, did a presentation on the hunger strike last year when it was on the list of potential events to cover.

“He did his report on it, and so I actually got in touch with [Pendakur], he got to interview her,” Vaid said. “He made this nice little styrofoam board of all the different events, the timeline, some clippings from different newspaper articles that I had saved and stuff like that.”

He also said that the knowledge he gained from the classes he took gave him a framework for understanding his background and confidence in defending himself in situations where people judge him by appearance.

Pendakur formerly worked as the director of Asian American and Pacific Islander Student Affairs at USC and traces her current equity role back to her time at Northwestern — she wants to be an advocate who can walk alongside students. Grace Lou, now an attorney in Manhattan Beach, California, said she works to make sure her kids learn about Asian American history.

Lin looks at her different records and copies of the Asian American Quarterly that she’s kept for 25 years. Meredith Melland, 14 East.

For Freda Lin, her college experiences with Asian American studies motivated her to be a k-12 educator and help kids like her realize that their backgrounds were important to American history. Currently living in San Francisco, Lin recently launched YURI: An Asian American Education Project with a partner. Named after Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese-American civil rights activist and supporter of Malcolm X, the project will work with k-12 schools to create curriculum on Asian American history.

“It’s always been this thread, this continual thread from my awareness and bringing Asian American [studies] to campus to where I am,” Lin said.

This spring, the first class of students majoring in Asian American studies will graduate from Northwestern in the midst of a global pandemic that is demonstrating that racism against Asian Americans is still pervasive. Their skills will be needed.

“If you are going to be living in this world, you need to understand diverse peoples and cultures and histories, and Asian American studies is a way to do that,” Yuh said.

She noted that the interdisciplinary nature and different modes of critical thinking offered in the program make students well-rounded, and they have gone to varied jobs at Google, financial companies, intelligence agencies and public office. Like their previous generations, the students are yearning for a chance for more, and that energy has kept the program alive, even when it was famished.

“Student support and student advocacy for the program, as well as student participation in the program, has meant that the Asian American studies program has been able to become an intellectual, academic, scholarly campus home for students and for faculty, where ideas thrive, people develop projects, and students grow and mature,” Yuh said. “I think that because of that, we will be able to thrive for a long time to come.”

Header image courtesy of Sumun Pendakur

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of the story stated that Vishal Vaid took “Hindu language” classes. The text has been updated to specify that Vaid took Hindi classes.

NO COMMENT