As protestors take to the streets of Chicago to push back against systemic issues of police brutality and racism in the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, a similar movement of support is brewing in the suburbs.

The last weekend of May, suburban protestors joined rallies and demonstrations organized by neighbors and community leaders, both to stand in solidarity with those in the city and to call to attention issues in their own towns.

Protestors lined Main Street in downtown Wheaton on May 30, holding signs to support the Black Lives Matter movement and stand in solidarity with protests downtown. Cam Rodriguez, 14 East.

Like those in Chicago, many protests in the suburbs sprung up organically and rapidly, often spread through social media, giving attendees only a few hours’ notice — a day, if they were lucky — before the rallies started.

“I found out about the event just a few hours before it took place, and the moment I found out, I knew that I had to go,” said Jordan Ryan, an assistant professor of New Testament at Wheaton College. “The moment I told my wife about it, we looked at each other for all of a second, and I just said, ‘We have to go.’”

“What drove me to the protest was the desire to do more than consume the news of systemic racism and the killing of George Floyd and many other Black lives and seek solidarity within the suburban communities,” said Joy Lee, who has worked in nonprofit management and education, and is married to Ryan.

Ryan and Lee attended a sidewalk protest on May 30 in Wheaton, Illinois, a western suburb of Chicago. The protest had been organized that morning, according to attendees and the organizer, Wendy Woodward.

“At 9 a.m., I texted a couple of friends asking if I was crazy … through Facebook and working with my friends we were able to bring together a couple hundred people by 1 p.m.,” Woodward said. “I must admit that I googled ‘how to do a protest’ just to make sure I was doing it legally.”

Woodward, like many protestors throughout the weekend, was joined by a family member — her 17-year-old daughter, Mackenzie.

“I woke her up on Saturday morning saying, ‘Wake up, honey, we are organizing a protest.’”

Wendy Woodward, the organizer of Wheaton’s protest on May 30, talks with attendees Jordan Ryan and Joy Lee as they display signs along Main Street. Cam Rodriguez, 14 East.

For residents of Wheaton and surrounding communities, the protest was more than just a stand in solidarity with events across the country, but a call to action for the town that has long been a hub for evangelical Christianity. Attendees lined Roosevelt Road and Main Street, which leads to the historic downtown area of the “Vatican of Evangelicals,” as it was called by The New York Times in 1978, to proselytize the masses and advocate for change.

“You need to love your neighbor more than yourself,” said Darcia Scafidi, a resident of neighboring suburb Winfield. “And when your neighbor sees that you are burying your head in the sand and not standing up for them, how else would they know that, other than me standing out there saying that I will not tolerate for you what I would not tolerate for myself?”

Scafidi, who is Black, found that the outpouring of support from her neighbors in a predominantly white community was uplifting and signaled a larger shift in the community.

“I am a person of color. I had no idea until I walked up and down [the street] that there were so many white people out there saying, ‘No, no, I’m not tolerating this anymore. This is not okay.’ It’s very heartwarming for me to see so many people close to my hometown saying, ‘No. This is not okay.’”

Will and Ema Chester brought a toddler, a baby and a sign to the protest in Wheaton on May 30. “They don’t know what’s happening yet, but we fully intend to raise them with an awareness of race, privilege and our calling to act on behalf of the oppressed,” he said. Cam Rodriguez, 14 East.

Will Chester is a youth pastor at the Church of the Resurrection, one of the many local churches throughout Wheaton. He, his wife Ema, and his two children protested along Main Street, holding a sign that said, “Jesus loves Black lives.”

“The history of the white church in the United States has most often been one of complicity and choosing to maintain the status quo over … following Jesus and demanding justice for people of color,” Chester said. “And I wanted people who aren’t Christians, especially those who assume that white evangelical Christians like me don’t care about Black people, to know that not all evangelicals fit the stereotype that gets pushed by both conservatives and progressives.”

“To me, ‘evangelical’ means taking the Bible seriously — and that means standing up against systemic racism.”

Lee agreed, and said she had conversations with friends wanting to stand in solidarity with Black North Americans.

“One common thread in the conversations were about where are the voices of solidarity from our Asian North Americans? How do we continue learning together beyond this moment and offline? The Christian faith is built on the teachings of Jesus Christ, the one who calls us to push back against systems of oppression.”

But despite the outpouring of support, the politically conservative roots of Wheaton still showed at the protest. Lee and Ryan felt targeted by one of the few counter protestors at the rally — a white man who had rolled down the window of his car and shouted that, “This is not Chicago,” and that the couple should, “Go back to where [they] came from.”

Plainfield Protests

In Plainfield, mask-clad protestors lined Illinois Route 59 and Route 126, hoisting signs calling for justice. Cam Rodriguez, 14 East.

Messages at a protest in southwest suburb Plainfield were similar, with poster board signs calling for justice and accountability. While protestors in Wheaton were beginning to mobilize along Main Street, attendees in Plainfield crowded at the intersection of Route 59 and Route 126, a congested thoroughfare for semi-trucks and residents, and chants of “Black lives matter” were often interjected with honks of support.

Lauren Chapman attended the protest with her mother, and said that it held big significance for her. Having grown up in Plainfield, Chapman experienced at a young age the ugliness of racism within the predominantly white suburb.

“In middle school, every day when I would walk home a car full of white males would drive by and yell out derogatory racist terms to me,” she said. “After experiencing that and other acts of racism I did not think our community could come together so strongly for these protests.”

The morning of the protest, Chapman looked back on history as an added reason for protesting within her hometown, particularly on the legacy set by those in the Civil Rights Era.

“I woke up Saturday morning thinking about the Civil Rights Movement and my grandparents, and how my grandfather, Lacy J. Banks, marched with Martin Luther King,” Chapman said. “I want to be able to tell my kids one day that I took a stand and fought for a good cause.”

The protest in Plainfield, like many others across the city and suburbs, was organized by two high school students, and followed a demonstration the night before that took place only five minutes down the road. Students made up a large portion of the crowd, and for Jon Gilmore, a high school sophomore, attending the protest gave him hope.

“I think something I don’t know gets talked about enough is that there’s a lot of hope,” Gilmore said. “Seeing this many people this excited and passionate about something I also care about really made me excited and ready to do more, and made me feel like we can actually do this — we have a chance to make the world a better place.”

Gilmore described a prayer circle at the protest. “I think that kind of showed that everyone there was a little sad and angry: all of the emotions that are normal to feel after this amount of injustice. But there’s a whole lot of hope for the future.”

“Don’t sugarcoat it” — tough conversations and family demonstrations

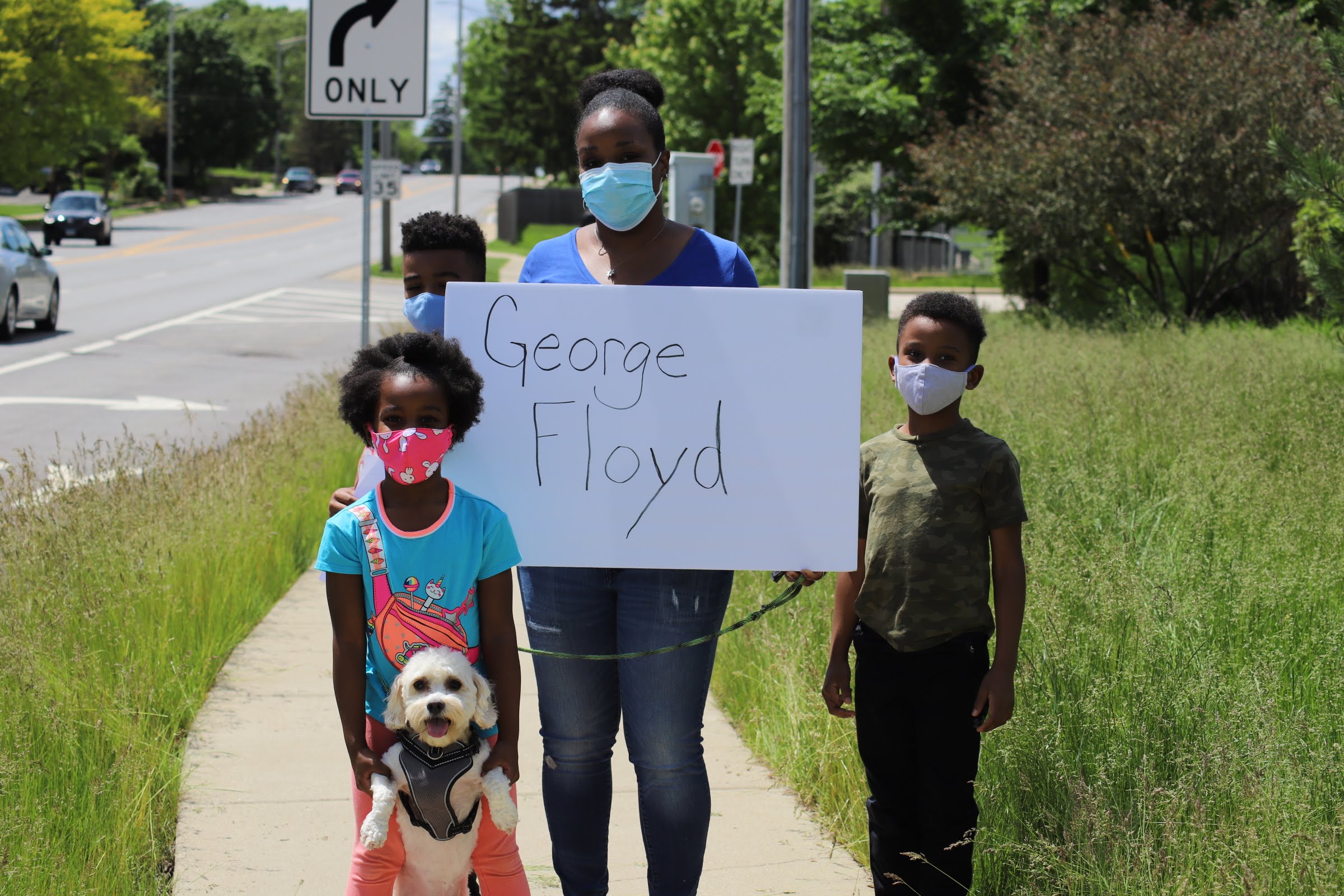

Crystal Smith and her children stand alongside Roosevelt Road in Wheaton at the protest on May 30. “I think it’s important for my kids to be aware of the world that they live in,” she said. Cam Rodriguez, 14 East.

The presence of families was a constant throughout the weekend: parents with strollers, propping up posters alongside diaper bags; siblings with signs, standing shoulder to shoulder on the sidewalk; a mother holding her child in one hand and a sign in the other.

But as more and more people attend protests for the first time, and are confronted with a family member doing so (or, in some cases, not doing so), conversations are being had at dinner tables and family meetings as to how we can best act as advocates for ourselves and allies for others.

“I think it’s important for my kids to be aware of the world that they live in so that there’s not a shock if ever they encounter racism or are in that kind of situation,” said Crystal Smith, who lives and protested in Wheaton. “I pray to God that they don’t ever, but the reality of the situation is that they might, and so I want them to be emotionally prepared for things and just prepared in general for life and the differences, unfortunately, that exist between people who don’t always look the same or don’t have the same beliefs.”

The night before the May 30 protest, at the dinner table, Smith had discussed George Floyd’s murder and protesting with her children, tying it to larger issues of police who abuse their power and how there are “good and bad people everywhere.”

“You know, the police are here to protect us. I don’t want you to be afraid of them. But just know that, you know, as someone who looks like us, if you get pulled over by the police, when you’re old enough to ride around with your friends, you may not get the same treatment as them,” she said.

Smith detailed how challenging the experience of explaining racism to her children was, particularly to her 9-year-old son. By the time Smith was nine, she said, she had already experienced racism firsthand.

“It was just amazing, you know — they don’t see the world as we do,” Smith said about her children. “It’s a good thing that they don’t have that lens, that they don’t have to feel that way about stepping outside. It’s wonderful, but I think that it would be most beneficial for those people that don’t look like us to have those important conversations with their children.”

Chapman, who attended the Plainfield protest, agrees.

“I think that NBPOC [non-Black people of color] could take it upon themselves to educate themselves on race,” she said. “I think it would be helpful to start things at home — have these conversations in your homes to have open [dialogue] about race and biases associated with race.”

“By educating themselves, NBPOC can become a strong ally, which is what we need: people with privilege to help us fight and fight for us,” she said.

Protestors filled Naperville’s Cantore Park on May 31, listening to a lineup of speakers and community members about racial injustice and the need for action. Cam Rodriguez, 14 East.

Many white and non-Black families, like Mary Beth Ressler, her husband and her children, had conversations about being allies and finding places to start with actively advocating against racism and racial injustice, both before and after the protests they attended. Ressler and her family attended a rally in Naperville’s Cantore Park on May 31, listening to speakers who spoke in front of a structure that only a week before had been vandalized with graffiti including white nationalist symbols.

“We talked to them specifically about George Floyd and other Black people who have unjustly died at the hands of police brutality,” said Ressler, who is a secondary education professor at North Central College in Naperville. “And it’s a difficult conversation to have with young kids and they were understandably upset, but we explained to them that the reason we are telling them this is because we, you know, we have important work to do as human beings and that our family’s white, and it’s our responsibility to do anti-racist work.”

Ressler detailed how her oldest son, who is eight, wanted to move up closer during the protest to listen to some of the speakers.

“I explained to him … that wasn’t our job. Our job was to stand in solidarity and support,” she said. “Of course, he asked me what solidarity meant.”

“I’ve had conversations with people that say, y’know, they’re just kids, preserve their innocence, but my response to that is, like, who’s preserving the innocence of the kid whose fathers are lost to this, or family members are lost to this? We’re not living in a fair society, and so I’d rather have them be critical thinkers than necessarily have childlike innocence.”

David Jansen, his wife Megan, and his kids (affectionately known as the “J-Crew”), hoisted signs along Main Street in Wheaton on May 30. Cam Rodriguez, 14 East.

For families handling conversations with their children about race for the first time, David Jansen, who attended the Wheaton protest with his wife, Megan, has a suggestion that was echoed by many protestors: don’t sugarcoat it.

“They need to feel the pain,” he explained. “The little ones, they can handle the truth. If they don’t get it from us, they’re gonna get it out there, and they’re gonna get it in a different way, in a slanted way, in a backwards way. So in parenting, you have to have these conversations with your kids, because this racism isn’t going to go away … we need to start educating the next generation and educate this stuff out of them.”

Ressler felt that the messages of anti-racist work that were being promoted at the Naperville protest by speakers, including Dana Davenport of the Naperville Community Television show Dana Being Dana and former Black Panther Party member Stan McKinney, are ones that she wants parents to pay particular attention to.

“I think it’s an important lesson to teach our kids, because it shows them that you need to do work to change the world,” Ressler echoed. “My kids are going to be white men someday. I hope to raise them to be doing that anti-racist work their whole lives.”

Darcia Scafidi, who attended the Wheaton protest, is married to an Italian American man; her son is biracial.

“He understands what it means to be an immigrant and come to a country and know nothing, and understands the Great Migration, and Jim Crow — he didn’t hear it in the history books, he learned it at the dinner table.”

Drawing on her years as a teacher, Scafidi recommends opening discussions with a resource, like a book, article or movie, and an intentional question at the beginning: how open are they to the conversation?

“Because otherwise it’s gonna end in a stalemate; that person has to decide at the very beginning of the conversation, otherwise you’re just spinning your wheels. You’re never going to change somebody’s mind, unless they’re open.”

Lee recommends being mindful and understanding that people make mistakes.

“Learn to unlearn what has been embedded in your culture and education system,” she said. “And remember that rooting out systemic injustices within institutions and ourselves is a marathon with milestones and not a 100-meter dash.”

She recommends resources from PhD student and anti-racist researcher Victoria Alexander, who posted a list of readings based on various jumping-off points and topics on her Twitter account.

“People often think of humanitarian work as something folks do during disasters or overseas, but I think it’s clear that the oppression of Black lives is a human rights violation. So there’s work to be done here, too,” Lee said. “There is often a sense of complacency in the suburbs and this notion that activism can only take place in the city. I think these past eight days have shown that to be untrue, and I hope that it is a start for suburbanites to rise [from] their slumber.”

Lauren Chapman and her mother protest in Plainfield on May 30, alongside Illinois Route 59. Cam Rodriguez, 14 East.

Header image by Cam Rodriguez, 14 East

Editors note: previously, it was written that Joy Lee currently works in nonprofit management and education. This has been corrected.

NO COMMENT