An editor’s note

It was a Friday morning back in October 2019 when I first visited the Austin Weekly Newsroom alongside a few 14 East staffers, our advisor, Amy Merrick, and instructor and Chicago Sun-Times reporter Evan F. Moore. The visit was a part of a course that Merrick and Moore were instructing together entitled “Chicago Undercovered.” Throughout the course, we had readings, discussions and visits with newsrooms in the city, all aimed at understanding the role of traditional media in perpetuating Chicago’s deep and systemic racial divides –– and how to dismantle this process.

A quick Google News search of “Austin, Chicago” yields very different results from that of “Oak Park,” the slightly more suburban enclave just west across Austin Boulevard, or of any North Side neighborhood. Instead of comprehensive coverage featuring local business and neighborhood events, mainstream coverage of Austin is often centered around violent crime.

The coverage in Austin is also disproportionate to the sheer size of the neighborhood. Austin is the city’s largest community area and was, for decades, the most populated area as well, with close to 100,000 residents, something that Austin Weekly News editor Michael Romain emphasized to us on that October morning. He stressed that not only is the West Side covered improperly, but that it’s often left out of mainstream coverage entirely.

We left the AWN newsroom that day with an understanding: The West Side needs more journalists. And not just more journalists who are going to parachute in, skim stats from a police report, extract community voices and call it a day. The West Side needs more journalists from the West Side. The West Side needs more journalists who are willing to sit down, have conversations and foster genuine relationships with neighbors, organizers, teachers and families, and publish stories and information that give power to the people, rather than trapping entire communities in harmful, negative narratives.

Around mid-November, I began the process of applying for a Seed Grant from Illinois Humanities, an organization that supports and sponsors humanities projects in Illinois that “engage a diverse public on ideas and issues that matter,” according to their website.

14 East had previously won the 2018 Seed Grant for the “14 East Water Testing Project.” Staff used the grant to test the water of 92 DePaul community members for lead and report the results.

We knew that we wanted the Seed Grant project to reach outside of our immediate community. We wanted to utilize our multimedia, research and social media skills to fulfill a real need for information. We thought a lot about the lessons from Merrick and Moore’s class and about things we’ve learned from other community news outlets, like City Bureau’s hierarchy of information needs. We thought a lot about what Romain had told us –– the West Side needs more journalists to dig into the questions, needs, truths and stories of the people who live there.

We proposed a project about housing in the Austin neighborhood. Housing is something I and several members of our staff write about with frequency, fascination and a dedication to engagement and research.

And in Austin, housing is a subject of the utmost importance. Like many predominantly Black neighborhoods in Chicago, Austin has faced decades upon decades of disinvestment by the city, tracing back to the Great Migration and Chicago’s nefarious roots in redlining.

That history is still visible today.

Aaron Allen is a West Sider, reporter and City Bureau alum. He recently published an article with WBEZ, “How the Green Line, A Pink House And 12 Cents Change How I See My City,” tying contemporary racially unequal mortgage lending practices in Chicago to his own experiences growing up in Galewood, a suburban pocket within the Austin community.

“Even as a kid growing up, I was always aware that my neighborhood stood in contrast to the rest of the West Side. Returning from family excursions downtown, I would press my face against the window of the car and watch the city change around me,” Allen said in his story. “I would see fewer businesses, more boarded-up buildings, more desolation the further west we drove — until we crossed back into Galewood.”

Allen and the team at WBEZ analyzed 168,859 home loans between 2012-2017, accounting for over $57.4 billion. The reporting found that only 8 percent of this money went to Black neighborhoods, as compared to 68 percent to white ones.

In a phone interview, Allen emphasized these inequities to me. He said that while disinvestment is certainly visible in many Black and Brown areas of Chicago, the West Side is sometimes left out of these conversations entirely.

“Especially being on the West Side, there aren’t well-invested pockets like you might find even on the South Side,” he said. “From the time you exit downtown headed west, between there and where I stay in Galewood, you see all the indicators of disinvestment. There’s a lack of businesses, a lack of stores … you see boarded up businesses along major streets.”

Allen also talked about a woman he interviewed for his piece about the West Side who said that “the private market just doesn’t work” for housing in the neighborhood, and Allen expanded on this need for an overhaul of housing investment and policy.

“The private market has to be intentionally disrupted [to address] the vast inequities we see,” Allen said. “There were laws put in place to explicitly exclude Black people and Black communities. And now we’ve taken a lot of the racist language out of these policies, but we’ve never done anything to really, truly address them and get people’s foot in the door. There has to be race conscious policies, economic policies, that give a leg up [to] the Black community.”

We wanted the Seed Grant project to address these inequalities and to utilize our resources as journalists at 14 East to give space to this conversation. In December 2019, 14 East was awarded $2,500 for our project proposal.

The original proposal outlined a plan for two to three community conversations in the Austin neighborhood, as well as canvassing sessions and online engagement over Facebook and Twitter to promote these events. Over the course of several months, we planned to gather input from residents as to what questions, observations or information needs they had about housing in their neighborhood. The money would be used to compensate reporters, for rental costs of spaces to hold our planned conversation events, to provide food at those conversations from local vendors, for printing a final brochure with reported information and finally, for a resource-fair style event in June, where we would wrap up the project.

MacArthur’s Restaurant in Austin

Our first community conversation was between community stakeholders that 14 East had worked with previously. Cassandra Norman and Terry Redman of South Austin Neighborhood Association as well as Liz Abunaw, the owner and operator of 40 Acres Fresh Market, met with the 14 East team at MacArthurs Restaurant in February. In our initial conversation, they outlined more organizations, activists and other community members to engage with and advised us in building guidelines for our future, larger conversations. We came away understanding that for this project to be something of value, we needed to become more familiar with existing activism and research that already exists and to bring this information to the people, not just publish a story on our website and walk away.

Cassandra Normal (left) and Terry Redmond (right) of South Austin Neighborhood Association

Following that meeting, we set out to canvas for our first community conversation. In early March, we handed out flyers at local businesses and to people up and down Madison Avenue, then again on Madison Avenue two weeks later. These canvassing sessions in and of themselves proved to be productive engagement. Between business owners and patrons occupied in their day to day, waving and nodding for us to place the flyers on the counter and let them get back to work, there were others who asked questions and gave feedback.

Our first community conversation took place at Austin Town Hall on March 3. Roughly 10 people showed up, some of whom were stakeholders we had been speaking with throughout this process. We set up groups, facilitated conversations with guided questions and over the course of two hours, collaborated with the handful of residents, activists and researchers who participated to build a list of housing-related issues in the Austin neighborhood that we could focus our reporting on.

Following that conversation, we began fleshing out story ideas, contacting sources and creating a new timeline for publishing and future events.

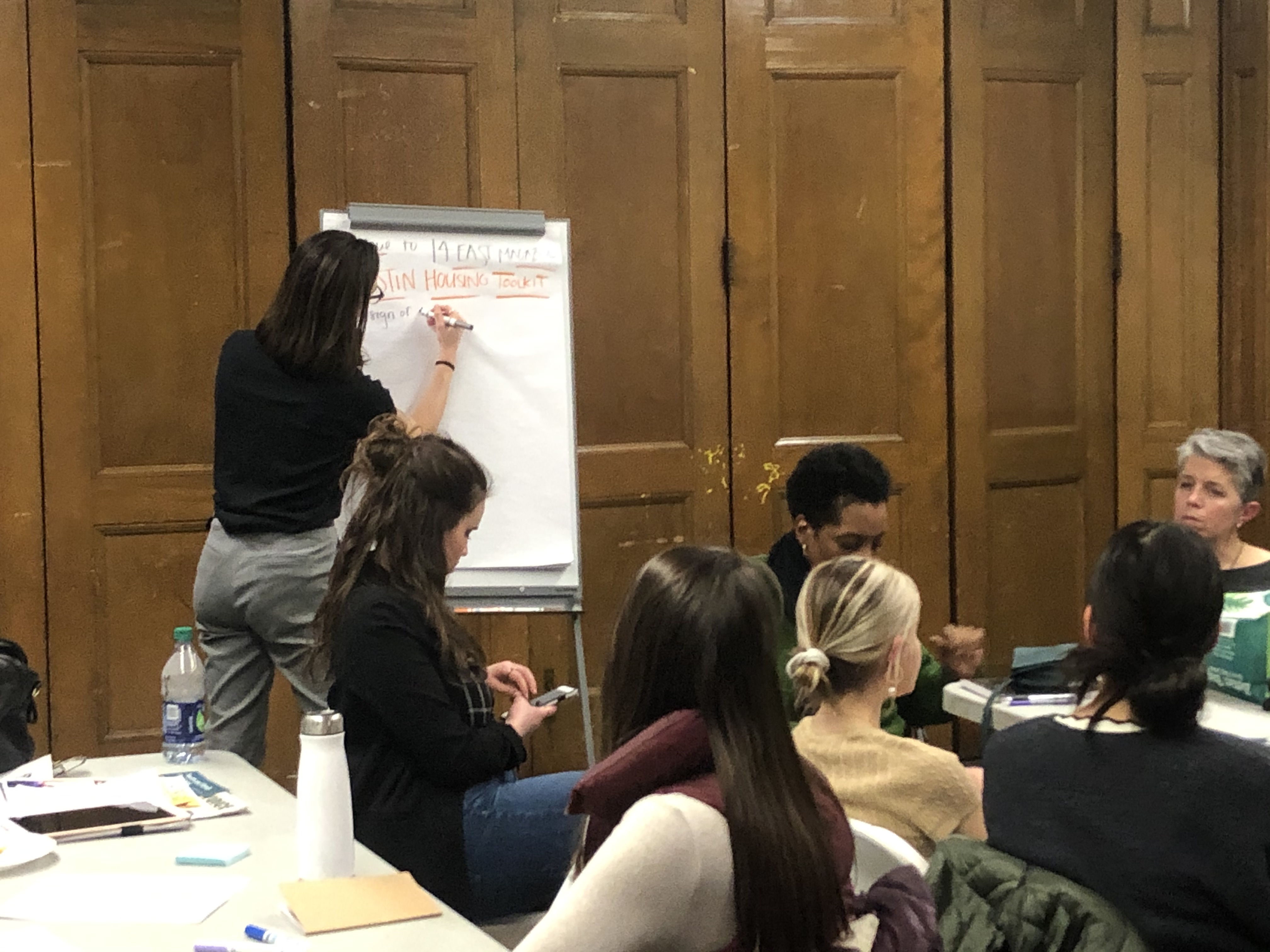

- Community conversation at Austin Town Hall in March 2020.

Then, the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Like many aspects of everyday life, this project was put on pause amid the fear and panic felt across Chicago. As COVID-19 numbers began to climb in the city, it became apparent that the crisis was devastating Black and Brown communities in Chicago far worse than their white counterparts. Over 70 percent of early COVID-19 deaths were among Black people, and in April, the Austin neighborhood was seeing some of the highest death rates in the city.

These were just the physiological impacts – economic fallout also hit the neighborhood hard.

We knew that talking about housing in the context of COVID-19 and the West Side was still important, perhaps more important than before. But to continue the process we had laid out for the project, serious adjustments would have to be made.

There were, of course, no follow up community conversations. No in-person canvassing. No resource fair was ever planned. After losing several weeks of work due to the reshuffling and readjusting from the pandemic, we had to shrink our scope.

So, we began calling people instead. Using public voter data, we individually called rows of residents in the 60644 zip code and talked to them about our project, about COVID-19, about their housing situations. These conversations were minorly successful –– many calls not making it far past an introduction, but a few sparked long conversations about life in the neighborhood.

In this process of adapting and readjusting our project to be accessible during the pandemic, we made the determination that a mailed fact sheet with some of our reported information would be an effective way to materialize our work and bring it to the community, rather than let information sit on the 14 East site alone. After this series publishes online, we’ll be translating some of the more essential aspects of our reporting into a mailer to be sent out to the zipcodes we reported in.

And of course, in our final days of reporting and writing, the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25 sparked demonstrations and protests across the country. In Chicago, the uprising is still persisting, with demonstrations almost every day.

Conversations about the systems of racial oppression that impact the landscape and lives in neighborhoods in Chicago and across the country are, in a big way, moving to the forefront of our civic discourse. Sharing information as a community and centering those who have been fighting to be heard for hundreds of years is a task that needs to be taken on by all newsrooms.

“It’s been really beautiful to see the amount of people, especially from the West Side, come together,” Allen said. “I think some of us from the West Side do have a chip on our shoulder, because we are left out of the conversation so much. So I think it’s really beautiful to see, in this moment, the amount of turnout for a lot of these events.”

When we first planned this project, we thought our publication in June would mark the end of our work. But we are realizing now that this is, truly, just the beginning of a conversation, of a relationship, of a process of reframing our journalism around serving real needs.

Back when we first began writing the proposal for this project, it felt logical enough to imagine months of engagement, events, and articles full of findings out of six months of reporting. However, in this series, what is reflected is not a project from start to finish, but the beginnings of a conversation. This series is just a glance at the stories that we have yet to tell and the connections we will continue to build in the Austin neighborhood.

“I really hope that this type of energy continues and that we continue. Our most affected communities are able to be helped in this revolutionary moment and we continue to push for no change in our communities,” Allen said. “We have to do it.”

Header illustration by Phoebe Nerem.

NO COMMENT