Furious shouting erupted from the back of the auditorium. Arabic words were spat through clenched teeth, their severity evident. Despite all his cultural sensitivity training from the Unites States military, Aaron Hughes knew no Arabic. He was helpless behind the microphone. All there was left to do was wait while this stranger ran at him, the man’s arms flailing violently in all directions as he got closer and closer to the stage. This is it, Hughes thought. This guy is going to come beat the s– out of me and I guess that is fine because it’s his country. Only moments away, the man’s face shined with sweat, red from the force of his heated words. As he finally reached the stage, a delayed translation came through Hughes’s earpiece.

“I just want to come up on stage and give this gentleman a hug,” rang through his brain and Hughes, without time to process this information, was suddenly wrapped in the arms of a stranger. Tears came instantly.

This is the origin story of the Tea Project: an organization using art to pay homage to the detainees of Guantanamo Bay and as an outlet for social justice dialogue, performance and expression – all rooted in tea. Performances and tea engagements took up temporary residence in Links Hall at 3111 N. Western Ave between April and March of last year.

Hughes was deployed to Iraq in 2003 after joining the Illinois Army Guard just outside of Chicago in North Riverside. Overseas, the interactions he remembers with the local population were limited, and prejudice ran deep within all civilian relations. Despite being in the midst of an invasion, the locals exuded an air of generosity and compassion that came forth in the form of tea.

“Not only are we occupying their space, their land, but at times when they had very specific needs around survival like food and water, we would refuse to provide these things that we had. And they would still offer us tea,” Hughes said.

Hughes and his entire unit would refuse it. Upon deployment, everyone was united in a profound distrust of the Iraqis and the Kuwaitis, so the local hospitality was far from welcome. Everything was Haji – a sloppy slang word used by U.S. soldiers for the Iraqi people as well as Middle Easterners more broadly. Everyone was Haji, their markets were Haji-markets, the trucks kicking up dust in the distance were Haji-trucks. Racialization worked to dehumanize the individuals that the army was instructed to interrogate, fight and kill. There was no use for their tea.

“We called it Haji-water. It could be poisoned, it could be all these things; you could never trust it,” Hughes said.

After the war, Hughes became an active member in Iraq Veterans Against the War. He advocated for VA benefits, reparations for those the war harmed and education about consequences for the invasion. On his trips back to Iraq as a peace delegate in 2009, Hughes was finally able to accept the generosity of the people he was forced to fight.

“I was crying and they sat me down and they gave me tea and that was the first time I had Iraqi tea,” Hughes said.

Tea is a common thread between Hughes’ experience overseas and the narratives of Arab people experiencing oppression, violence and Islamophobia everywhere. The Styrofoam cup art instillation was inspired by the experiences of Chris Arendt, a colleague of Hughes and former Guantanamo Bay guard.

Hughes created an intimate window into the ritual of tea by creating 779 marked cups. One for each detainee of Guantanamo Bay. They’re now cast in porcelain with the hopes of being returned to their rightful owners after release from the United States military prison that detains them.

Inside Guantanamo Bay, Styrofoam cups turned into canvases. Grown men delicately inscribed them with intricate arrangements of flowers every day of their imprisonment. For the detainees of Guantanamo Bay these cups were a form of expression created in the cells they occupied indefinitely. The marks left on them by the prisoner’s fingernails turned the cups into security threats, collected meticulously every night by guards and given to military intelligence to record and dispose of.

“He thought it was a ridiculous process because every time he would go down to these detainees to collect these cups, they would be scrawled all over with flowers,” Hughes said. “Just flowers.”

Arendt wanted to use his experiences to bring justice to the detainees, and the cups often remained at the forefront of his mind. He realized that this act of creation became a way for him and the prisoners he guarded to hold onto their humanity in a place that was built to dehumanize. Hughes was able to turn Arendt’s memory into something tangible with the help of Amber Ginsburg, the artist behind the cups now made of porcelain.

At Links Hall, Styrofoam cups serve as a stark reminder of the life locked indefinitely inside Guantanamo Bay (Ivana Rihter, 14 East Magazine)

At Links Hall, the first contact guests of a tea engagement had was with these teacups. As masses of people filtered in along walls lined with cups, the sound of ceramic clinking and wood creaking filled the air as everyone picked theirs for the evening. The tea served was sweetened, but unconventionally so. Michael Rakowitz, who brewed the evening’s tea, spoke to the gallery, sharing memories of his grandmother relentlessly begging his grandfather to make an Iraqi specialty.

“She complained for years that no one could make date syrup the way my grandfather used to make it,” Rakowitz said. “The tea you are drinking here tonight to honor these men and the stories of Arab people everywhere is sweetened not by honey or sugar, but date syrup from Iraq.”

The tea is earthy and dark against the luminously white ceramic cups, all scribbled with distinct floral patterns. These are not decorative flowers, but hold the weight of a certain history and humanity behind them.

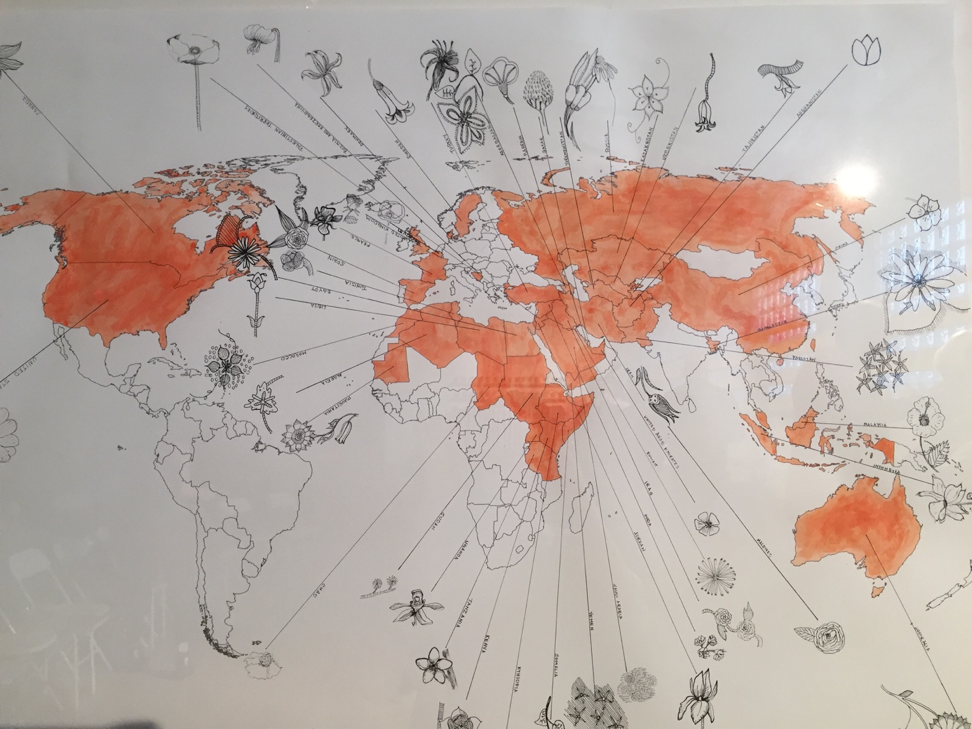

Hughes and Ginsburg have crafted 779 teacups for each person held captive in Guantanamo Bay. Each cup is ornately designed to include the state flower of each detainee, their names and their country of origin. 220 tea cups were made for the Afghan majority and on every cup are 220 tulips. Every cup is a statistical document.

“They have names,” Ginsberg said. “This might seem like a small thing. But when you are in a detention camp or a prison, you do not have a name; you have a number.”

According to all accounts, the original cups from Guantanamo were destroyed. Hughes submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the Department of Defense for any documentation of these cups with no response.

From the desolate cells of Guantanamo Bay, the Styrofoam teacups have not been forgotten by the outside world. The Tea Project has made Chris Arendt’s accounts of the detainees hope into something tangible.

“This love story and these flowers are really for me kind of the heartbeat of story. It shows the impulse to make something exists even in one of the darkest places imaginable places I could dream of,” Ginsburg said.

Header image: A map from the Tea Project’s exhibit at Links Hall, mapping the national flower of each detainee in Guantanamo Bay (Ivana Rihter, 14 East Magazine)

NO COMMENT